Perinatal Cerebral Infarction

Laura R. Ment

Barbara R. Pober

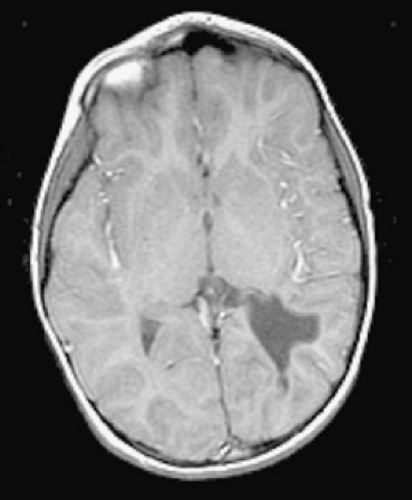

Perinatal cerebral infarction, or stroke, may be defined as the severe disorganization or even complete disruption of the gray and white matter architecture of the developing brain caused by embolic, thrombotic, or ischemic events. Infarcts in early fetal life result in cortical neuronal loss and architectural changes resembling polymicrogyria. Strokes later in gestation are characterized by cavitary changes, or porencephalies, and appear similar to well-defined adult cerebral infarctions. In full-term neonates with stroke, cortical necrosis and hemorrhage into gray and subcortical white matter structures may be apparent.

Although strokes have been reported to occur in approximately 5% of infants coming to postmortem examination, conservative estimates suggest that neonatal stroke is recognized in approximately 1 per 4,000 live births per year, and this diagnosis should be entertained in those infants who have disorders ranging from congenital microcephaly to neonatal seizures to hemiparesis. Findings in an infant with perinatal cerebral infarction depend on both the timing in gestation and the underlying pathophysiology of the insult.

NEONATAL STROKE

Cerebral infarcts in the term neonate may be the result of embolic, thrombotic, thrombocytopenic, infectious, iatrogenic, or ischemic events, and several factors predispose the

late-gestation fetus and newborn to stroke. The coagulation pathway in the newborn favors thrombosis, the hematocrit of the term neonate is high, and cerebral blood flow values of infants are low when compared with older children and adults. Finally, the patent foramen ovale permits more than one-half of all blood flow to pass to the brain. Most strokes in full-term neonates occur in the distribution of the middle cerebral arteries, and more than 75% are found in the left hemisphere. This finding may be explained by the relatively straight pathway of the left carotid artery to the developing brain and favors a thromboembolic mechanism for stroke; the right carotid artery follows a more tortuous course. Furthermore, recent data suggest that at least 30% of neonatal strokes are attributable to sinovenous thrombosis.

late-gestation fetus and newborn to stroke. The coagulation pathway in the newborn favors thrombosis, the hematocrit of the term neonate is high, and cerebral blood flow values of infants are low when compared with older children and adults. Finally, the patent foramen ovale permits more than one-half of all blood flow to pass to the brain. Most strokes in full-term neonates occur in the distribution of the middle cerebral arteries, and more than 75% are found in the left hemisphere. This finding may be explained by the relatively straight pathway of the left carotid artery to the developing brain and favors a thromboembolic mechanism for stroke; the right carotid artery follows a more tortuous course. Furthermore, recent data suggest that at least 30% of neonatal strokes are attributable to sinovenous thrombosis.

Pathology

Data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey from 1980 through 1998 demonstrated that the most common causes of neonatal stroke include hematologic disorders, infection, and cardiac anomalies. Less than 5% of infants with stroke had the now well-recognized characteristics of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, suggesting that other etiologies must be considered. The risk factors for neonatal stroke are found in Table 35.1.

Thromboembolic Causes

In many infants, focal stroke is caused by thromboembolism from the placenta, the heart, or intra- or extracranial vessels. Several studies have suggested that coagulation disorders, including the factor V Leiden mutation, and protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III deficiencies are responsible for up to half of all strokes in neonates. Proteins C and S are natural anticoagulants that regulate the cascade of coagulation, inhibit factors Va and VIIIa, and activate fibrinolysis. The factor V Leiden mutation is attributable to a missense mutation of the factor V gene, thereby making it resistant to normal cleavage by activated protein C (APC). Protein C is activated by the thrombin–thrombomodulin complex and degrades factors Va and VIIIa. The factor V Leiden mutation results in increased thrombin generation and thus a shift to hypercoagulability (Fig. 35.1). The prothrombin G20210 and MTHFR (encodes NAPDH) 677TT mutations, which also cause a shift toward hypercoagulability, have been implicated in neonatal stroke.

TABLE 35.1. RISK FACTORS FOR NEONATAL STROKE | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In addition, lipoprotein A is a plasma lipoprotein homologous to plasminogen, and elevated lipoprotein A levels have been found in neonates with focal stroke. Similarly, phospholipids are involved in the activation of protein C, and maternal antiphospholipid antibodies, including anticardiolipin and the lupus anticoagulant, interfere with normal coagulation. Both have also been reported in association with neonatal stroke.

Finally, infection (Fig. 35.2), indwelling catheters, and polycythemia are all associated with a hypercoagulable state, and all have been associated with focal central nervous system lesions in infants.

Sinovenous Thrombosis

Risk factors for sinovenous thrombosis in neonates include perinatal complications and dehydration. Perinatal complications reported with sinovenous thrombosis and stroke include hypoxia, premature rupture of the membranes, maternal infection and neonatal infections of the head and neck. Prothrombotic disorders have also been associated with this cause of neonatal stroke.

Causes of Hemorrhagic Stroke

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree