Fig. 1

Anatomy of the annular pulleys of the fingers (Copyright © 1990 American Society Surgery of the Hand. All rights reserved)

Patient Assessment

Trigger Thumb

The most common history associated with pediatric trigger thumb is that the parents notice that the child cannot extend the interphalangeal (IP) joint of the thumb. Sometimes a traumatic event, such as catching the hand in the door, may bring the parent’s attention to this condition; the traumatic event is not causative for the trigger thumb, but trauma is a common history in that it brings this condition to the parent’s attention. Ten to 15 % of cases of pediatric trigger thumb will present with intermittent locking or catching of the thumb IP joint.

Presentation most commonly occurs in the 2-year-old child, although age at presentation can range from babies to school age children. Although many authors have described this condition as congenital trigger thumb , there is no evidence that this condition is present at birth. In fact, multiple studies support that trigger thumb is an acquired, not congenital, condition and should be properly termed pediatric trigger thumb (Kikuchi and Ogino 2006; Rodgers and Waters 1994; Slakey and Hennrikus 1996). Nonetheless, most classifications of congenital upper extremity anomalies include the pediatric trigger thumb (Ekblom et al. 2010; Oberg et al. 2010).

Physical examination reveals normal formation and development of the thumb. Congenital clasped thumb or hypoplastic thumb can be excluded if normal size of the thumb is noted with normal flexion and extension creases, as well as a history of previous normal use of the thumb. Clasped thumb also is defined as a contracture at the metacarpophalangeal joint, not the interphalangeal joint. A palpable nodule will be present just proximal to the MCP joint flexion crease consistent with node of Notta. Limited active and passive extension of the thumb IP joint will be present (Fig. 2a). With longstanding IP joint flexion positioning, secondary deformities occur including hyperextension through the thumb MCP joint.

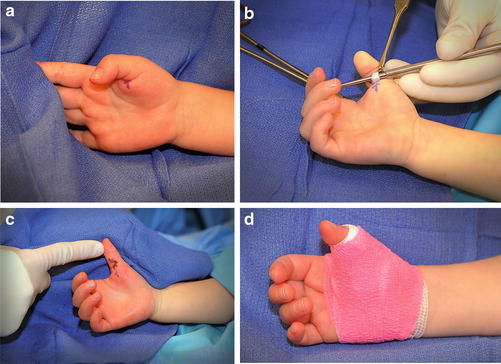

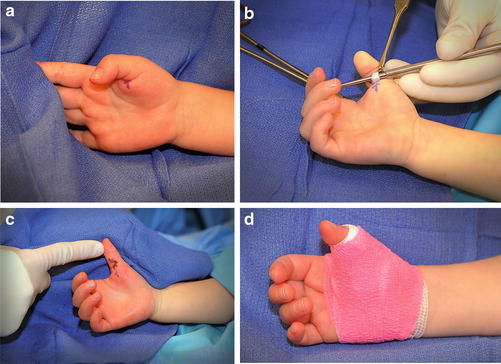

Fig. 2

(a) Clinical presentation of locked flexed IP joint due to pediatric trigger thumb. (b) After release of the A1 pulley, the tendon is inspected revealing the pathognomonic node of Notta. (c) After surgical closure of the Bruner (shown here), transverse, or oblique incision, full passive range of motion of the digit is achieved. (d) Postoperative dressing allows tendon gliding and protects the wound

No further diagnostic testing for trigger thumb is necessary, as the history and physical examination are pathognomonic for this condition.

Trigger Finger

Triggering is seen infrequently in children; once they have experienced the unpleasant sensation, most children avoid it. For this reason, some children hold the digit in extension, refusing to flex, or hold the digit in flexion, refusing to extend. Triggering fingers are certainly more uncommon than trigger thumbs. Physical exam will reveal normal formation and development of the digit, with normal flexion and extension creases, which excludes hypoplasia or symphalangism. A palpable nodule will often be present at the A1 pulley level, consistent with a locked digit . Additionally, in conditions such as mucopolysaccharide storage disease, nodules may be present at the A1 pulley and/or the A3 pulley. In these cases, mucopolysaccharide deposits along the flexor tendon will be palpable and will coincide with coarse digits which are shortened and broadened. Further diagnostic testing is necessary in children who present with trigger digits. Urinalysis for mucopolysaccharide storage diseases, particularly for children who have concomitant symptoms of carpal tunnel, is necessary. Additionally, inflammatory diseases should be ruled out, including inflammatory arthropathies.

Treatment Options

A literature review was performed to review the treatment outcomes for pediatric trigger thumb. In the 24 articles reviewed, 1,187 patients with 1,449 thumbs were assessed. 50.4 % were girls and 49.6 % were boys. Right side was involved in 55.2 %. Bilateral involvement was present in 25 % of cases. Mean age at first presentation was 26.4 months with 19 % of the patients presented before 6 months. According to prospective studies, pediatric trigger thumb is not present at birth (Moon et al. 2001; Rodgers and Waters 1994; Slakey and Hennrikus 1996).

Few authors tried to differentiate between thumbs with a fixed flexion deformity and those which snapped or triggered. The most common position (85 %) was, however, with IP joint locked in flexion, as shown in Table 1. Locked extension has been reported (Watanabe et al. 2001; Wood and Sicilia 1992). Slakey et al. found in 15 children a flexion contracture of the IP joint averaging 35° (20–50) (Slakey and Hennrikus 1996). For White and Jensen, the IP joint is most frequently locked at about 30° of flexion (White and Jensen 1953), and for Baek et al., the mean flexion deformity is 26.5° (Baek et al. 2008). The other authors did not report the amount of flexion contracture.

Table 1

Literature review of clinical examination at the time of presentation

Authors | Triggering (percent) | Locked (percent) |

|---|---|---|

Skov et al. | 15 | 85 |

Watanabe et al. | 37 | 63 |

Moon et al. | 6 | 94 |

Mulpruek et al. (JPO) | 0 | 100 |

Tsuyugushi et al. | 34 | 66 |

Slakey and Hennrikus | 0 | 100 |

White and Jensen | 33 | 77 |

As shown in Table 2, the reported spontaneous recovery rate was highly variable, from 0 % to 66 %. The time before spontaneous recovery was also variable, ranging from 1 to 24 months. However, most of these authors did not mention if the thumbs were triggering or if they were locked in flexion at initial examination. Furthermore, most authors did not report if “spontaneous recovery” included any residual flexion contracture.

Table 2

Literature review of spontaneous recovery rate and timing

Authors | Rate of spontaneous recovery (percent) | Time before spontaneous recovery (months) |

|---|---|---|

Baek et al. | 63 | 60 (range, 24–128) |

Moon et al. | 34 | 5 (range, 1–24) |

Mulpruek and Prichasuk (JHS) | 24 (within 3 months of initial symptoms) | 1.75 (range, 1–4) |

Tan et al. | 66 (especially in younger age group) | N/A |

Dunsmuir et al. | 49 | 7 |

Dinham and Meggitt | 30 if <6months of age | Within 12 |

12 if >6months of age |

Some authors found a high rate of spontaneous recovery, from 24 % to 66 % (Table 2). For Baek et al., the average time for resolution was high (60 months), but those authors chose to proceed with the period of observation in order to avoid surgery (Baek et al. 2008). For Dinham and Meggit, the patients who present before 6 months of age can be safety watched for 12 months because there is an expected spontaneous recovery rate of at least 30 % (Dinham and Meggitt 1974). In their study, if trigger thumbs were noticed between the ages of 6 and 30 months, the spontaneous recovery rate was about 12 %.

For other authors (De Smet et al. 1998; Ger et al. 1991; Hudson et al. 1998; Skov et al. 1990), no spontaneous recovery occurred in their patients. For Skov et al., the mean duration of the symptoms, from when they were first seen by a physician until a trigger release, was 7 months (range, 2–43); no patient had spontaneous recovery in the interval between the onset of the symptoms and the operation (Skov et al. 1990). Ger et al. found that none of their 11 patients with diagnosis before 6 months of age resolved without surgery despite an average of 40 months of observation (Ger et al. 1991).

Management of trigger thumb and trigger fingers is controversial. The possibility of spontaneous resolution exists and has been controversial regarding age and timing of resolution (Ger et al. 1991). Nonoperative treatment options include splinting. Tsuyuguchi et al. reported on 83 trigger digits in 65 children treated with a coiled spring splint, maintaining the IP joint in neutral or hyperextension (Tsuyuguchi et al. 1983). He reported 75 % resolution within 9 months with splint compliance. The average age of these children was 2 years at the time of presentation. Nemoto et al. reported on 43 trigger thumbs and fingers in 33 children who were treated with splinting (Nemoto et al. 1996). Twenty-four of the 43 digits recovered over a mean of 10 months. The remaining cases dropped out of treatment or were lost to follow-up.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree