The interview is the most important aspect in determining the true reason for the visit. Due to different levels of maturity in each age group of children, different approaches to communication may be used. Including parental figures in the discussion is key.

Gynecologic problems often experienced by the pediatric patient include vulvovaginitis, trauma, foreign bodies, prepubertal vaginal bleeding, abnormal pubertal development, urogenital abnormalities, and genital tumors.

The examination presents a unique set of difficulties that may be overcome by following a few key guidelines:

Give the patient a sense of control.

Display a caring and gentle attitude at all times; the initial evaluation can set the tone for all future examinations.

The physical exam should include an overall assessment of other organ systems. This allows the patient to feel more comfortable in the exam room and the

examiner to gain an overall appreciation of height, weight, skin disorders, hygiene, and other indicators of pubertal development.

If the child is very young or has suffered physical abuse, she may need to be evaluated under anesthesia.

Make it clear to the child that the examination is permitted by her caregiver and that if anyone else tries to touch her genital area, she should tell her caregiver.

A chaperone should be present during the physical exam.

The abdominal exam can be facilitated by placing the child’s hand over the examiner’s hand.

Palpate the inguinal regions to identify potential hernias or gonadal masses.

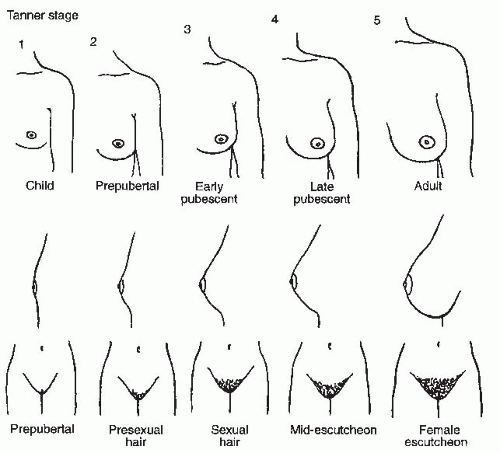

Tanner classification of the external genitalia and breast development should be used to quantify pubertal changes (Fig. 34-1).

Frog-leg posture: child supine with feet together and knees bent outward. Commonly used in the younger patient.

Figure 34-1. Tanner stages of development. (From Beckmann CR, Ling FW, Barzansky BM, et al. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1995:8, with permission.)

Knee-chest position: when combined with a Valsalva maneuver, allows for assessment of the introital area. Using an otoscope for magnification or nasal speculum may help with visualization when the primary complaint is vaginal discharge or foreign bodies.

Supine lateral-spread method: often sufficient enough to allow for visualization of the vestibular structures

Mother’s lap positioning: Allow the patient to sit in her mother’s lap, knees bent, heels on mom’s knees; combine with lateral traction of the labia for adequate exposure.

When a child is uncooperative or evaluation of the genitalia is not optimal, an exam under anesthesia or a return visit may be necessary.

Note perineal hygiene, presence of pubic hair, hymenal configuration, size of the clitoris, and the presence of vulvovaginal lesions or vaginal discharge.

Careful inspection of the hymen must be completed before pelvic examination. A Foley catheter balloon can be placed behind the hymen and filled to visualize a redundant hymen.

Lateral downward traction of the labia allows visualization of the hymen in prepubertal girls.

Specimens may be collected using a small urethral Dacron swab. A second technique employs an empty butterfly catheter attached to a syringe and saline is flushed and aspirated to obtain a mix of secretions. A pediatric feeding tube attached to a 20-mL syringe also allows for vaginal irrigation.

Use of “extinction stimuli” can greatly facilitate a first pelvic exam. Use a distracting stimulus to draw attention from a second stimulus. For example, press a nonexamining finger into the patient’s perineum before touching the introitus and allow the patient to acknowledge the presence of its pressure.

Proper instrument selection is important. Speculum exams are rarely appropriate in the prepubertal patient. Often, the hymenal ring is too tight to accommodate even a pediatric speculum. A nasal speculum can be used for an exam under anesthesia if speculum exam is necessary.

Rectoabdominal examination may aid in examination of the uterus in a patient who cannot tolerate a vaginal exam.

Common exam findings:

Newborn child: It is important to recognize that maternal estrogen influences physical development of the newborn child. Vulvar edema, whitish pink vaginal mucosa, vaginal discharge, and breast enlargement may be normal in the newborn and should regress in the first 8 weeks of life.

Toddler-prepubertal child: Unestrogenized vaginal mucosa appears thin, hyperemic, and atrophic. Capillary beds may appear like roadmaps and are often mistaken for inflammation, especially around the sulcus of the vestibule and in the periurethral area.

A labeled sketch of the external genitalia should be included in the medical record with a diamond-shaped space used to represent the vestibule of a child in the supine position. Twelve o’clock should represent the clitoris and 6 o’clock should represent the posterior fourchette.

Key components include assessing Tanner stage, description of labia majora; labia minora; urethral meatus; hymen; and the presence of any discolorations, hemangiomas, vulvovaginal lesions, or vaginal discharge.

Given changes in Pap smear guidelines (see Chapter 45), a pelvic exam is not always necessary in the adolescent patient.

Pelvic exams should be performed in patients younger than the age of 21 years, only if indicated by chief complaint and history.

An evaluation of external genitalia can still be performed to confirm normal anatomy and development.

Testing for sexually transmitted infections such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomoniasis can be performed from urine samples or vaginal swabs.

If indicated, a Huffman (1/2 × 4 inches) or Pederson (7/8 × 4 inches) speculum is most appropriate for use in this patient population.

Although the focus of this chapter is on the evaluation and management of prepubertal pediatric patients, several recommendations should be noted for the evaluation of adolescent patients.

Although evaluation of Tanner stage may be appropriate at an initial visit, clinical breast exams are not necessary unless indicated by complaint or history until age 20 years.

Vaginal discharge is the most common gynecologic complaint in the prepubertal girl and accounts for 40% to 50% of visits to a pediatric gynecology clinic.

Presents as vaginal discharge that can stain the underclothing

Vulvar burning or stinging may occur when urine comes into contact with irritated, excoriated tissues.

Note the duration, consistency, quality, and color of the discharge.

Symptoms may also include erythema, tenderness, pain, pruritus, dysuria, or bleeding.

Anaerobic infections may have a foul odor.

Bloodstains can occur if Shigella, group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus, foreign body, or trauma is present.

Poor hygiene; back to front wiping; use of harsh soaps, bubble baths, and lotions; trauma associated with play; genital manipulation with a foreign body or contaminated hands; close fitting, poorly absorbent clothing, including prolonged exposure to a wet bathing suit; thin, unestrogenized, alkaline vaginal mucosa; and lack of labial development may predispose to vulvovaginitis.

Ask the child to demonstrate proper front to back wiping.

Note the type of diaper and frequency of changes in younger children.

Ask about recent systemic infections, new medications, bed-wetting, dermatoses, and nocturnal perianal itching.

Presentations for vulvovaginitis are extremely variable, ranging from no discharge to copious secretions. Erythema, edema, and excoriations are commonly noted. Evidence of poor perineal hygiene may be evident, with stool seen on the vulva or between the labia.

Collect a sample of any discharge for microscopic examination and culture. Avoid contact with the hymen in prepubertal children.

Carefully note the configuration of the hymen and evaluate for any signs of trauma. The perianal skin should also be examined.

Vaginoscopy should be considered to exclude a foreign body, neoplasm, or abnormal connection with the gastrointestinal or urinary tract, especially in recurrent cases or those associated with bleeding.

Normal prepubertal vaginal flora includes lactobacilli, α-hemolytic streptococci, Staphylococcus epidermidis, diphtheroid, and Gram-negative enteric organisms, especially Escherichia coli. Candida is present in only 3% to 4% of prepubertal girls.

Although many cases of vulvovaginitis may be nonspecific, the most common pathogenic bacteria causing vulvovaginitis include group A Streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and E. coli.

Children may pass respiratory flora from the nose and oropharynx to the genitalia area, making this a possible etiology of vulvovaginitis.

Children with chronic, nightly episodes of vulvar or perianal itching should be evaluated for Enterobius vermicularis.

Shifts in flora resulting from inoculation by bacterial, viral, and yeast can result in inflammation and discharge. Several of these pathogens may be indicative of sexual activity or abuse. Sexually transmitted diseases are typically the result of sexual abuse.

Obtain cultures if symptoms are persistent or if there is purulent discharge. Treatment with antibiotics is indicated when an infectious pathogen is identified (Table 34-1).

Twenty-five percent to 75% of cases are likely caused by poor hygiene, soaps, obesity, foreign bodies, association with upper respiratory infections, and irritating clothing in the setting of unestrogenized mucosa.

Treatment includes discontinuation of the causative agent, perineal hygiene, sitz baths, loose-fitting clothing, cotton underwear, hypoallergenic soaps, wet wipes, and emollients.

If there is no resolution in 2 to 3 weeks, evaluate for a foreign body or infection.

A trial of estrogen cream can be used if other etiologies are ruled out to thicken the vaginal mucosa and make it less sensitive.

Most common in girls aged 2 to 4 years. The foreign bodies can vary from wads of toilet paper, buttons, or coins to peanuts and crayons. Antibiotics should be started before removal.

Presence can be an indicator of sexual abuse.

Retained foreign bodies in the vagina often present with bloody, brown, or purulent discharge of several weeks duration. Persistent vaginal discharge in a toddler or young girl warrants an exam under anesthesia.

Genital pruritus, abdominal pain, or fever may be present.

If the object remains undetected, peritonitis can develop from the ascension of purulent secretions into the fallopian tubes.

A careful examination of the vaginal wall for any defects or additional embedded foreign bodies should be performed after the object has been removed. If the rectovaginal septum is involved, a temporary colostomy with delayed repair of the vaginal and rectal tissues may be indicated.

TABLE 34-1 Treatment of Specific Vulvovaginal Infections in the Prepubertal Child | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ectopic ureter: May result in urinary leakage. Often detected on prenatal ultrasound. After birth, an ultrasound can be used for diagnosis, followed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if indicated.

High hymenal opening: may impair vaginal drainage; hymenectomy is curative in these cases.

Urethral prolapse (see the following text).

Lichen sclerosis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis of the vulva may all present with symptoms similar to vulvovaginitis. These conditions may respond to topical corticosteroids.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree