Pediatric Dermatology

Daniel P. Krowchuk

Walter W. Tunnessen Jr.

Complaints involving the skin are common reasons why parents seek medical care for their children. Data from the 2003 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey showed that in approximately 8% of visits to primary care providers for children, a cutaneous diagnosis was recorded. The volume of skin-related problems makes it necessary for physicians who care for children to gain some facility in recognizing and managing the most common cutaneous disorders.

Dermatology is a visual specialty. With experience, most common problems affecting children’s skin can be recognized, including the subtle variations in presentation. For uncommon cutaneous problems, atlases (including electronic atlases [see Resources at the conclusion of this chapter]), texts, or other sources can be used to aid in identification. As in most medical specialties, an organized approach to the problem is most helpful in leading to the correct diagnosis.

TERMINOLOGY

This chapter is designed to assist the reader in the diagnosis of skin problems. The approach is based on morphologic

appearance. If clinicians can describe what they see, they already may have conquered a major obstacle to diagnosis. Describing cutaneous lesions is not as easy as it may sound. Practice in using descriptive terminology is the key to success. The sections of this chapter are based primarily on lesion morphology. The first step in an organized approach to skin lesions is to define the descriptors.

appearance. If clinicians can describe what they see, they already may have conquered a major obstacle to diagnosis. Describing cutaneous lesions is not as easy as it may sound. Practice in using descriptive terminology is the key to success. The sections of this chapter are based primarily on lesion morphology. The first step in an organized approach to skin lesions is to define the descriptors.

A macule is a circumscribed area of change in skin color without elevation or depression of the skin surface; macules generally are less than 1 cm in diameter. A patch is a large macule, greater than 1 cm in diameter. Papules are solid, elevated, palpable lesions less than 0.5 cm in diameter; nodules are larger papules that can lie in the epidermis or in the dermis or subcutaneous tissues. Plaques are elevated, plateau-like lesions formed most frequently by the confluence of papules.

A vesicle is a fluid-filled blister less than 0.5 cm in diameter; a bulla is a blister that is 0.5 cm or greater in diameter. A pustule is a blister filled with cellular debris, generally white blood cells, which gives the lesion a white or yellowish color. A wheal is the result of localized edema in the skin. It is pink or pale and usually is rounded or flat-topped, sometimes with irregularly shaped margins. Wheals are evanescent, lasting less than 24 hours in any one place. They are associated almost invariably with pruritus.

Telangiectases are permanent superficial dilations of venules, capillaries, or arterioles that may or may not blanch with pressure. Lichenification is a thickening of the skin in which the normal skin markings usually are accentuated; prolonged rubbing or scratching of the skin is necessary to produce this change. Crusts are accumulations of dried serum, blood, pus, or other exudative materials on the surface of the skin. Scales are flakes of skin, either loose or adherent, that are composed of compact keratin. An area of sclerosis is one that feels indurated or thickened and has lost its normal elasticity. The surface coloration may show hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, or both. Normal skin appendages (i.e., hair and sweat glands) are absent from the sclerotic area.

An erosion is a superficial epidermal loss that has a moist base; an ulcer is a deeper lesion, extending into the dermis and sometimes below it. Atrophy of the skin produces a depression in the skin surface. If the epidermis is atrophic, the skin appears thin and translucent, and it wrinkles when the edges of the affected area are pinched.

In addition to the foregoing types of morphologic changes described, the pattern formed by the lesions on the skin should be noted. Lesions may be arranged in lines, as are the linear vesicles seen in allergic contact dermatitis due to poison ivy; they also may be grouped, as are the vesicles observed in herpes simplex, or dermatomal, as in herpes zoster. The distribution of the lesions also should be noted. For instance, seborrheic dermatitis commonly involves not only the scalp but the eyebrows and nasolabial folds as well. Psoriasis often affects traumatized areas, such as the elbows and knees. Pityriasis rosea presents as ovoid, slightly scaly thin plaques arranged along lines of skin stress, particularly on the back where they mimic the appearance of the branches of a fir tree. Acne occurs almost exclusively on the face, shoulders, back, and chest.

The headings of most of the sections that follow are morphologic descriptors of cutaneous lesions. The most common dermatologic conditions are covered in these sections, with the emphasis placed on clinical appearance, differentiation from other lesions, and suggestions for management. Some conditions can have different clinical presentations. In these cases, the condition is presented in each pertinent section. Therefore, discussions about contact dermatitis can be found under Vesicles, Scaling and Dry Lesions, and Pruritic Lesions.

SKIN LESIONS IN THE NEONATAL PERIOD

Macules and Patches

Hyperpigmented

Mongolian Spots

Present at birth, mongolian spots are blue-gray or blue-green and represent areas of dermal melanosis. They occur most frequently in the lumbosacral area (Fig. 129.1) and over the shoulders. Occasionally, they are found on the anterior trunk and extremities; only rarely are they seen on the face. More than 90% of African Americans, 80% of Asians, and 46% of Hispanics have mongolian spots, whereas fewer than 10% of Caucasians have them.

Although these lesions tend to disappear with time (usually by the ages of 4 to 5 years), the color change persists in 5% of children. Because mongolian spots have been mistaken for bruises associated with child abuse, educating parents and nursery or day-care workers regarding the congenital nature of the patches is important. Mongolian spots are believed to result from arrested migration of melanocytes from the neural crest. Because the spots are benign, no therapy is necessary. Malignant degeneration has not been reported.

Café au Lait Macules

Café au lait macules (CALMs) are light to dark brown in color, well defined, and range in size from a few millimeters to many centimeters. In a cohort of 4,641 newborns, 12% of African American and 0.3% of Caucasian infants had at least one of these lesions. African American infants were more likely to have more than one lesion: 4.4% had two, and 1.8% had three or more. None of the Caucasian infants had more than one lesion. The incidence of CALMs increases with age; among children under the age of 10 years, 13% of Caucasian and 27% of African American children have at least one CALM. Multiple CALMs are associated with neurofibromatosis type 1; they also can be seen in other syndromes. (See Hyperpigmented Macules in the section Skin Lesions in Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence, later.)

Linear and Whorled Nevoid Hypermelanosis

Linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis is the term used to describe linear, streak-like, or swirling patterns of hyperpigmentation that follow the lines of Blaschko, the lines that reflect the pattern of migration of embryonic cells from the neural crest. Pigmentation is present at birth or within the first few weeks of age. Over time, it becomes more prominent and then stabilizes. Linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis most often is a disorder limited to the skin, although occasional infants will have skeletal or developmental abnormalities. The condition is believed to result from mosaicism of neuroectodermal cells prior to migration. The differing skin colors represent two separate cell populations.

Nevus of Ota

A nevus of Ota is an uncommon, bluish or gray-brown patch of pigmentation that occurs on the skin of the face, usually in the distribution of the first and second branches of the trigeminal nerve. Perhaps two-thirds of affected infants have an associated ipsilateral bluish discoloration of the sclera. Although they are most common in Asians, the lesions may occur in deeply pigmented individuals. Approximately one-half are congenital; the rest appear later, often during the second decade of life. Histologically, a nevus of Ota is identical to a mongolian spot and likely results from errors in migration of melanocytes from the neural crest. Unlike the mongolian spot, however, the nevus of Ota does not undergo spontaneous regression. If scleral pigmentation is present, glaucoma may occur. Malignant degeneration occurring within a nevus of Ota is rare. Management options for the nevus include the use of a covering cosmetic or treatment with a pigmented lesion laser.

Nevus of Ito

A patch of hyperpigmentation similar to the nevus of Ota but occurring over the shoulders, in the supraclavicular areas, and on the sides of the neck, the upper arms, and the scapulae is known as the nevus of Ito. These lesions persist throughout life. Treatment options are analogous to those for the nevus of Ota.

Congenital Melanocytic Nevi

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are present in 1% of newborns (color Fig. 68.1 in color section). Most of the nevi are small, well defined, and flat or minimally elevated. When compared with normal surrounding skin, CMN are at increased risk for the development of malignant melanoma. For small lesions (e.g., those less than 1.5 to 2 cm) and those of intermediate size, this risk is low (likely less than 1% to 2%) and malignant transformation is highly unlikely before puberty. However, the lifetime risk of melanoma developing in a large lesion (e.g., greater than or equal to 20 cm) is as high as 6% to 7% and this change may occur early in life (Fig. 129.2).

Infants with small or intermediate-sized lesions may be managed with observation during childhood. Surgical intervention may be considered in the unlikely event that lesions change in size or appearance. Although controversial, some experts advise elective excision of these lesions at puberty depending on their location and the anticipated cosmetic outcome of the procedure. The management of large CMN also is controversial. Owing to the risk of malignant change, many experts advise excision, although the size and distribution of the nevus may render removal difficult and disfiguring. Thus, the management of CMN must be individualized based on the nature of the lesion and the family’s preference. Finally, infants with large CMN overlying the head or posterior trunk may have underlying neurocutaneous melanosis, a benign or malignant melanocytic infiltration of the leptomeninges. Infants with such lesions may benefit from magnetic resonance imaging of the head or spine.

Hypopigmented

Ash Leaf Macules

Hypopigmented macules are present in 0.4% to 0.6% of newborn infants. A single lesion in an otherwise healthy infant likely represents an isolated cutaneous finding. However, multiple hypopigmented macules should raise concern that the lesions represent ash leaf macules associated with tuberous sclerosis, an autosomal dominant disorder characterized classically by the triad of seizures, mental retardation, and adenoma sebaceum. Ash leaf macules are the earliest sign of tuberous sclerosis and often are present at birth. They are oval-shaped hypopigmented macules measuring 2 to 12 mm that typically are located on the trunk or extremities. In lightly pigmented individuals, they may be recognized more easily by the use of a Wood lamp in a darkened room.

Hypomelanosis of Ito

Linear or streaked hypopigmentation following the lines of Blaschko is termed hypomelanosis of Ito. As with linear and whorled hypermelanosis (discussed earlier), hypomelanosis of Ito likely reflects cutaneous mosaicism. Most affected infants are well; rarely, the disorder may be associated with seizures, mental retardation, or skeletal or ocular abnormalities.

Nevus Depigmentosus

The name nevus depigmentosus is a misnomer since lesions are hypopigmented, not depigmented. Lesions usually are solitary, large, irregularly shaped patches that are present at birth and located on the trunk or extremities. A nevus depigmentosus usually represents an isolated cutaneous abnormality that will persist throughout life.

Papules

White

Milia

Single or multiple 1- to 2-mm yellowish white papules, known as milia, occur in some 40% of newborns. These lesions are found most commonly over the cheeks, forehead, nose, and nasolabial folds (Fig. 129.3). Much less commonly, they may be found on the trunk or extremities. Histologically, they represent cysts composed of keratin and are similar to Epstein pearls, the whitish papules noted on the palates of many newborns. Treatment is unnecessary; the cysts disappear in the first few weeks of life.

Yellow

Sebaceous Gland Hypertrophy

Stimulation of the sebaceous glands (which lie at the base of the pilosebaceous units) by androgens often leads to the appearance of tiny, yellowish papules over the nose and, occasionally, other parts of the face. Because androgen levels decline over time, the appearance of these papules is transient, and clearing occurs in a few weeks. No therapy is necessary.

Erythematous

Erythema Toxicum

The erythematous macules, papules, and (sometimes) vesicles of erythema toxicum (color Fig. 68.9 in color section) occur in at least one-half of term newborns; they are less common in premature infants. Generally, the lesions appear between the first 24 and 48 hours of life and are described best as resembling flea bites. The individual lesions tend to last less than 24 hours, but new lesions can appear during the first 2 weeks of life and, occasionally, later. Clinical difficulty may arise in separating the lesions of erythema toxicum from those of more ominous conditions, such as staphylococcal pustulosis or herpes simplex virus infection. Identification of large patches of macular erythema surrounding the lesions is one way to recognize erythema toxicum. If uncertainty exists, a vesicle or pustule may be opened and the contents placed on a glass slide and stained with a Wright stain. In erythema toxicum, microscopic examination will reveal the predominance of eosinophils. A peripheral eosinophilia often is present as well. To exclude the possibility of staphylococcal pustulosis, a Gram stain and bacterial culture may be performed. If herpes simplex virus infection is a concern, a Tzanck smear, direct fluorescent antibody test, polymerase chain reaction, or viral culture may be obtained. The cause of erythema toxicum has not been elucidated. No treatment is necessary for this benign condition.

Neonatal Acne

Comedones, erythematous papules, and pustules—all resembling the acne of adolescence—may occur in the neonatal period, generally at 2 to 4 weeks of life. Male infants are affected primarily, and the lesions generally occur on the cheeks and almost never are seen on the chest and back. Androgenic stimulation of the sebaceous glands is responsible for the appearance of the lesions. Generally, the eruption disappears in weeks or months, and no therapy is required. Occasionally, in severe or prolonged cases, topical erythromycin or 2.5% benzoyl peroxide can be prescribed. Pustules suggesting neonatal acne may be caused by Malassezia furfur or M. sympodialis yeasts in a condition called neonatal cephalic pustulosis (see Vesicles and Pustules, later). A potassium hydroxide scraping may differentiate this condition from acne.

Miliaria

Miliaria is the term applied to lesions that occur as the result of sweat duct obstruction and rupture. Three forms exist: miliaria crystallina, miliaria rubra (the most common type), and miliaria pustulosa. Miliaria crystallina is a tiny, teardrop-like, clear, fragile vesicle caused by the superficial plugging of sweat ducts. The lesions appear shortly after birth (particularly on the forehead), have no surrounding erythema, and disappear rapidly without intervention. Miliaria rubra, in contrast, is associated with surrounding erythema as a result of extravasation of sweat into the epidermis, causing localized inflammation (Fig. 129.4). In miliaria pustulosa, more intense inflammation results in the formation of pustules. Young infants seem particularly prone to miliaria, perhaps in part because of parental concern about keeping them warm. The areas most likely to be affected are the face, skin folds of the neck, shoulders, and diaper area. Therapy consists of removing excessive clothing, avoiding the application of thick emollients (that may obstruct sweat ducts), and maintaining a comfortable environmental temperature.

Vesicles and Pustules

Transient Neonatal Pustular Melanosis

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis presents as pustules, ruptured pustules with a collarette of scale (that represents the remnants of the pustule roofs), and small hyperpigmented macules (in the sites of previous pustules). It occurs in 4% to 5% of African American infants and in fewer than 1% of Caucasian infants. The face, chin, neck, and shoulders are the areas most commonly affected. If vesiculopustules are present, they disappear within 1 to 2 days. In contrast, the pigmented macules may take weeks or even months to fade. The pustules are 1 to 3 mm in diameter, usually are flaccid, and have no surrounding erythema (see color Fig. 68.10 in color section). Most have very little content on rupturing, including perhaps a few neutrophils. The cause of this disorder is unknown, but it appears

to be an entirely benign condition. A Gram stain of the contents of a pustular lesion should prove most helpful in differentiating transient neonatal pustular melanosis from bacterial pustulosis. No therapy is necessary.

to be an entirely benign condition. A Gram stain of the contents of a pustular lesion should prove most helpful in differentiating transient neonatal pustular melanosis from bacterial pustulosis. No therapy is necessary.

Neonatal Cephalic Pustulosis

A condition that may mimic neonatal acne is neonatal cephalic pustulosis caused by infection with the yeasts Malassezia furfur or M. sympodialis. At 2 to 3 weeks of age, inflammatory papules and pustules appear. Unlike neonatal acne, however, neonatal cephalic pustulosis is not characterized by comedones and lesions are distributed more widely, involving the scalp and trunk, as well as the face. To confirm the diagnosis, a potassium hydroxide preparation performed on a scraping of a lesion will reveal yeast spores. Neonatal cephalic pustulosis resolves without treatment but a topical antiyeast preparation may be applied to hasten its disappearance.

Congenital Candidiasis

Congenital cutaneous candidiasis is an uncommon disorder that is acquired in utero. Lesions are present at birth or develop shortly thereafter. The newborn’s skin often is diffusely erythematous and scaly. Tiny papules, vesicles, and pustules also are present. Examination of a scraping of the lesions should reveal the budding hyphae and pseudohyphae of Candida. Congenital candidiasis typically is limited to the skin, although premature infants may develop systemic involvement with pneumonia or sepsis. Cutaneous lesions are treated with a topical antiyeast preparation (e.g., nystatin).

Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

Vesicular lesions, whether grouped (as is typical) or scattered (as sometimes occurs in the neonatal period), always should suggest the possibility of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The majority of infants in whom herpes infections develop are born to mothers who are unaware of their own infection with the virus. Infection usually is acquired during passage through the infected birth canal, although ascending infection, particularly in association with premature rupture of the amniotic membranes, also is recognized. Neonatal HSV infection usually has its onset during the second or third week of life, but it may appear at birth or as late as 4 weeks of age.

Three forms of infection are recognized, each accounting for approximately one-third of all cases. Skin, eye, and mouth (SEM) infection begins at a mean of 11 days of age. Classically, infants present with clustered vesicles on an erythematous base. Lesions are concentrated on the head, particularly in areas of trauma, such as the site of placement of a scalp electrode (Fig. 129.5). Over several days, the vesicles become pustules, rupture, and form crusts. Occasionally, lesions will be widespread or in a distribution mimicking that of herpes zoster. Involvement of the mucous membranes produces shallow ulcers. If untreated, as many as 70% of infants with SEM infection develop disseminated disease.

Disseminated HSV infection has its onset at a mean of 11 days of age producing symptoms and signs suggestive of bacterial sepsis. Multiple organ systems are involved, including the liver, lungs, brain, and adrenal glands. Approximately 60% of affected infants also have skin lesions. The mortality rate associated with disseminated disease is high, even with effective treatment. Central nervous system infection begins at a mean of 17 days of age and is heralded by fever, altered sensorium, seizures, and coma. Sixty percent of affected infants have associated skin lesions.

The importance of immediate diagnosis of HSV infection cannot be overemphasized. Suspicious lesions should be tested by viral culture or polymerase chain reaction. In experienced hands, rapid diagnosis may be obtained via the performance of a Tzanck preparation. Parenteral acyclovir therapy should be administered without delay.

Neonatal Varicella

Neonatal varicella is an uncommon condition resulting from in utero infection in the 2 to 3 weeks before delivery. The lesions in neonates are similar to those seen in older infants and children, with crops of macules and papules developing into teardrop-like vesicles. The diagnosis is suspected by a maternal history. A Tzanck preparation will reveal multinucleated giant cells, but this finding does not differentiate between varicella and herpes simplex virus infection. Because disease may be severe, it is recommended that newborns whose mothers develop varicella 5 days before to 2 days after delivery receive varicella-zoster immune globulin.

Incontinentia Pigmenti

Incontinentia pigmenti (IP) is a rare genodermatosis with cutaneous abnormalities that occur in four stages. The earliest lesions are vesicles on erythematous bases that are arranged in a linear pattern on the trunk or extremities (Fig. 129.6; color Fig. 68.11 in color section). The lesions are present at birth or appear within the first 2 weeks of life. Individual lesions last 1 to 2 weeks but new lesions may appear for months. In this stage, IP often is confused with herpes simplex virus infection or impetigo. The second stage, which may overlap with the first, is characterized by verrucous (wart-like) papules located primarily on the extremities, but not necessarily at the sites previously affected by vesicles. This stage peaks at 12 to 26 weeks of age and resolves within 1 to 2 years. The third stage is one of tan to slate-gray hyperpigmentation that is arranged in a linear or whorled pattern on the trunk and extremities. This stage

also resolves gradually. The final stage, which may or may not occur, is composed of subtle, hypopigmented, atrophic patches of skin, especially on the legs.

also resolves gradually. The final stage, which may or may not occur, is composed of subtle, hypopigmented, atrophic patches of skin, especially on the legs.

FIGURE 129.6. Diffuse, purplish papules and nodules create a blueberry-muffin appearence in an infant with congenital rubella. |

IP is an X-linked dominant disorder caused by mutations in the NEMO gene. More than 97% of cases occur in females, suggesting that the condition is lethal for males in utero. It is a multisystem disorder affecting tissues derived from the neural crest. The majority of patients have extracutaneous disease involving the central nervous system (e.g., seizures, spastic paresis, microcephaly, or mental retardation), eye (e.g., strabismus, blindness, cataracts, or optic nerve atrophy), teeth (e.g., cone-shaped or irregularly shaped teeth), hair (e.g., alopecia), and bones (e.g., hemivertebrae, extra ribs, or syndactyly). Thus, children with IP require a multidisciplinary approach to management.

Eosinophilic Pustular Folliculitis

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an uncommon disorder that usually occurs in neonates. However, a more widespread and persistent form has been described in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. The disease is characterized by recurrent crops of pruritic, follicular, papulopustular lesions. The lesions tend to coalesce into plaques and occur most commonly on the scalp, face, chest, and back. Smears from the pustules show eosinophils, and peripheral eosinophilia is common. The lesions are sterile. The cause of the lesions is not known and the course varies. Treatment with topical corticosteroids of moderate potency has met with modest success.

Bullae

Sucking Blisters

Infants commonly suck their hands or fingers in utero. Occasionally, a thick-walled bulla on the dorsum of the hand, fingers, or forearm will result (Fig. 129.7). Their characteristic appearance and location and the observation of the infant sucking the affected area are helpful clues to this diagnosis. Treatment is supportive; a topical antibiotic and dressing may be applied as needed.

Bullous Impetigo

Bullous impetigo is caused by infection with strains of Staphylococcus aureus that elaborate toxins (exfoliative toxins A and B) that damage intercellular adherence resulting in the formation of bullae. It may occur at a few days of age, but generally it begins during the second or third week. Individual lesions are bullae that have a small rim of erythema. The bullae rupture easily, leaving an eroded, moist base that forms a crust and is surrounded by a rim of scale, the remnant of the blister roof. To confirm the diagnosis, the contents of a bulla may be cultured and a Gram stain performed.

FIGURE 129.7. Clustered vesicles of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection that developed at the site of a scalp electrode. See Color Figure 129.5 in color section. (Courtesy of Alec Wittek, MD.) |

Infants who appear well and have limited disease may be treated with an oral antistaphylococcal antibiotic. If signs of systemic infection are present, however, the infant should be evaluated appropriately and treated parenterally.

Elaboration of exfoliative toxins also may lead to staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, characterized by generalized erythema and the appearance of bullae, particularly in areas of trauma. There may be widespread loss of skin resulting in fluid loss and thermal instability. (See Bullae in the section Skin Lesions in Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence, later.)

Epidermolysis Bullosa

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) represents a group of rare hereditary diseases. The disorders result from defects in proteins involved in anchoring the epidermis to underlying structures. This, in turn, causes skin fragility with vesicles, bullae, and erosions. Depending on the disease type, involvement of the mucosae of the mouth or gastrointestinal or respiratory tracts may be present. Some forms of EB present at or shortly following birth with blisters and erosions resulting from delivery or handling (see color Fig. 68.16 in color section). The diagnosis of EB is based on family history, clinical findings, and cutaneous biopsy. Treatment is supportive, including gentle handling and bathing; the use of a soft nipple for feeding and loose-fitting diapers and clothing; and the application of a topical antibiotic to erosions. EB is discussed more completely later in this chapter (see Bullae in the section Skin Lesions in Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence, later).

Congenital Syphilis

Bullae and vesicles are an unusual presentation of congenital syphilis (Fig. 129.8). Most common on the extremities, they rupture rapidly, leaving an eroded surface. More commonly, flat-topped papules and plaques are seen that affect the mucocutaneous junctions, including the angles of the mouth and perineum (e.g., condyloma lata). Ovoid, slightly scaly, salmon-colored macules may also be present on the trunk and extremities (Fig. 129.9).

Purpura

Hemorrhagic lesions may occur on the skin of newborns for a variety of reasons. Infectious causes always should be considered, including bacterial and congenitally acquired infections.

Congenital Rubella

Purpuric lesions of infants infected with rubella virus in utero are caused most commonly by thrombocytopenia. On occasion, the purpuric lesions take on an infiltrative or nodular quality, producing a blueberry-muffin appearance (Fig. 129.10). The lesions actually are areas of extramedullary hematopoiesis rather than true cutaneous hemorrhage.

Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection

Petechiae in conjunction with intrauterine growth restriction, hepatosplenomegaly, and hyperbilirubinemia always should raise the question of congenital infection. Cytomegalovirus is the most prevalent of these infections. Most of the purpuric lesions are the result of thrombocytopenia. Blueberry muffin–like lesions also have been documented.

FIGURE 129.9. A tan-yellow plaque of a sebaceus nevus on the forehead. (Courtesy of P. J. Honig, MD.) |

Plaques and Nodules

Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis

Subcutaneous fat necrosis is a disorder of unknown cause that often occurs in association with birth trauma. Lesions typically are not present at birth but appear within the first weeks of age. The areas most commonly affected are the cheeks, buttocks, back, arms, and thighs. Lesions are irregular, hard, erythematous, or violaceous nodules that seem nontender. The size of the nodules varies. Occasionally, the lesions may become calcified, but generally they resolve spontaneously in 1 to 2 months without scarring. Some infants may develop symptomatic hypercalcemia that must be treated appropriately. No therapy of the skin lesions is necessary.

Nevus Sebaceus

The nevus sebaceus (of Jadassohn) is present at birth and usually is found on the scalp (color Fig. 68.3 in color section). The area is devoid of hair, slightly raised, smooth or with a velvety texture, and yellow to yellow-orange. Lesions vary in size and can be found on the face as well (Fig. 129.11). Sebaceous nevi represent benign hamartomas containing an increased number of sebaceous glands. Most represent isolated cutaneous

abnormalities but large or extensive lesions may be associated with mental retardation, seizures, or ophthalmic or skeletal malformations. Due to a small risk of malignant transformation (e.g., to a basal cell carcinoma) after puberty, elective excision may be considered at adolescence.

abnormalities but large or extensive lesions may be associated with mental retardation, seizures, or ophthalmic or skeletal malformations. Due to a small risk of malignant transformation (e.g., to a basal cell carcinoma) after puberty, elective excision may be considered at adolescence.

FIGURE 129.12. Pemphigus syphiliticus, a widely disseminated vesiculobullous eruption in an infant with early congenital syphilis. See Color Figure 129.8 in color section. (Courtesy of Charles Ginsburg, MD.) |

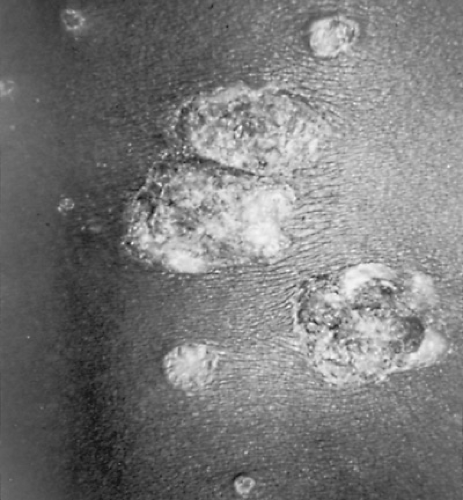

Epidermal Nevi

Epidermal nevi usually are present at birth but may appear during childhood or adolescence. They are verrucous-appearing, skin-colored or somewhat hyperpigmented papules or plaques that measure 2 to 10 cm in size (Fig. 129.12). Over time, lesions become darker, thicker, and rougher and may develop an unpleasant odor. Large or extensive linear lesions may indicate the presence of a neurocutaneous disorder with central nervous system (e.g., mental retardation, seizures), eye (e.g., strabismus), or skeletal (e.g., hemihypertrophy, kyphoscoliosis) abnormalities, and may be a feature of the Proteus and CHILD syndromes. The cause of epidermal nevi is not known but they represent hamartomas (benign tumors composed of normal but disorganized skin components). There is no risk of malignant transformation. If treatment is desired, application of a keratolytic agent, surgical excision, or laser therapy may be considered.

Sclerema Neonatorum

Sclerema neonatorum is an uncommon, rapidly spreading thickening of the subcutaneous tissue that occurs in preterm or ill infants during the first few weeks of life. The skin becomes tight, shiny, and nonpitting. Affected infants usually are seriously ill with other problems and rarely survive once this condition appears.

Dermoid Cysts

The small, rubbery, smooth subcutaneous nodules characteristic of dermoid cysts occur most frequently on the head and neck. Congenital lesions formed from embryonic ectoderm, they are lined by stratified squamous epithelium. Almost 40% are periorbital, and approximately 30% occur in the eyebrows. The lesions usually are solitary and asymptomatic, and they are managed by surgical excision. Lesions in the midline of the scalp or forehead or at the glabella may have an intracranial extension. Therefore, imaging of the bone and central nervous system should be conducted prior to excision.

Ulcers

Aplasia Cutis Congenita

Aplasia cutis congenita is characterized by a congenital absence of the skin. Affected infants usually exhibit a single lesion that may be a round or oval ulcer or atrophic scar that is located on the scalp at or near the vertex (Fig. 129.13). Individual lesions range in size from 1 to 3 cm. Occasionally, there is an associated defect in the cranium. Although aplasia cutis congenita most often represents an isolated cutaneous abnormality, it may be associated with limb abnormalities, sebaceous or epidermal nevi, epidermolysis bullosa, or other malformations. Treatment rarely is required as ulcers heal spontaneously. For infants with large lesions, skin grafting may be required.

Vascular Lesions

Salmon Patch (Nevus Simplex)

Salmon patches are the most common vascular lesions in infancy, seen in almost one-half of all newborns. These dull-pink macules composed of dilated dermal capillaries are most prevalent over the glabella, eyelids, and nape of the neck. Facial lesions tend to fade with time, generally within the first years of life. Neck lesions, however, may persist. The macules often are called stork bites (when located at the nape) or angels’ kisses (when located on the face). During crying, older infants and children may demonstrate flushing in areas of previous lesions that have faded.

Port Wine Stains

The benign salmon patch must be differentiated from the port wine stain, which is a congenital, permanent vascular malformation composed of mature vessels. Port wine stains (PWSs) are reddish or reddish purple and typically are darker than salmon patches (Fig. 129.14). They may occur anywhere on the body, although they are seen most commonly on the face. Infants with PWSs involving the distribution of the first and second branches of the trigeminal nerve (upper and lower eyelids, respectively), all three branches of the trigeminal nerve, or both sides of the face are at risk for Sturge-Weber syndrome. In this sporadic disorder, the vascular malformation involves not only the skin, but also the ipsilateral leptomeningeal vessels, particularly those in the parietooccipital region. Slow flow through these vessels causes hypoxic injury that, in turn, may result in seizures or contralateral hemiparesis. The vascular malformation also may affect the ipsilateral eye. Abnormalities of the choroid and episcleral vessels may lead to retinal detachment or glaucoma, respectively. PWSs on the extremities usually represent an isolated abnormality and only rarely are associated with overgrowth of the extremity (Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome). Because PWSs tend to become darker and thicker with time and may develop surface bleeding, children with significant facial PWSs should be referred for consideration of pulsed dye laser therapy early in life.

Harlequin Color Change

Harlequin color change is a curious phenomenon usually noted in the first few days of life in low-birth-weight infants. When such infants are placed on their sides, a sharp midline demarcation develops in the color of their bodies, with the upper one-half turning pale and the lower one-half turning deep red. A change in position results in resolution of the color change. The phenomenon can last for a few weeks and is attributed to a temporary imbalance in the regulatory mechanisms of the autonomic nervous system.

Hemangiomas

Hemangiomas are benign vascular tumors that proliferate during the first 6 to 9 months of age and then begin to involute, resulting in complete regression in most children. Hemangiomas may be present at birth but typically appear at 2 to 4 weeks of age. They are observed in as many as 10% of 1-year-olds. In some newborns, a hypopigmented macule, within which are telangiectatic vessels (a prehemangioma), heralds the appearance of a hemangioma. Superficial hemangiomas (often called strawberry hemangiomas) occur in the upper dermis. Deep hemangiomas appear as nodules with normal overlying skin and a bluish discoloration. Lesions with superficial and deep components are termed mixed hemangiomas (color Fig. 68.4 in color section).

Hemangiomas grow rapidly during the first 6 months of life, reach a quiescent stage when the patient is 6 to 12 months old, and then begin to regress when the child is between 12 and 18 months old. Signs of regression include patches of gray on the surface of the lesion (Fig. 129.15). By the time the patient is 5 years old, 50% of lesions will have regressed; by age 9, 90% will have done so. After regression, an area of atrophy, telangiectases, or hypopigmentation may remain. With large lesions, redundant skin may be the major cosmetic defect. Deep hemangiomas may not show complete regression.

Complications of hemangiomas are infrequent. Erosions are the most common complication, particularly for lesions in the diaper area (Fig. 129.16, color Fig. 68.4 in color section).

Hemangiomas that become eroded are painful, may become infected, and are prone to scar. They should be treated with a barrier cream and, if infected, an oral antibiotic. If they fail to heal within 1 to 2 weeks, consultation with a pediatric dermatologist is indicated. Bleeding occurs rarely and usually responds well to the application of direct pressure. Infants with multiple cutaneous hemangiomas (color Fig. 68.5 in color section) occasionally have associated visceral lesions in the central nervous system, lungs, liver, or intestines. If present, visceral lesions may result in high-output cardiac failure or hemorrhage. Most infants with systemic involvement present by 2 months of age with respiratory distress, hepatomegaly, a heart murmur, or anemia. The presence of multiple cutaneous hemangiomas should prompt the conduct of a careful history and physical examination. If suspicion exists about visceral involvement, initial screening studies might include a complete blood count, chest radiograph, abdominal ultrasonography, and stool for occult blood. Other potential complications of hemangiomas are presented in Table 129.1.

Hemangiomas that become eroded are painful, may become infected, and are prone to scar. They should be treated with a barrier cream and, if infected, an oral antibiotic. If they fail to heal within 1 to 2 weeks, consultation with a pediatric dermatologist is indicated. Bleeding occurs rarely and usually responds well to the application of direct pressure. Infants with multiple cutaneous hemangiomas (color Fig. 68.5 in color section) occasionally have associated visceral lesions in the central nervous system, lungs, liver, or intestines. If present, visceral lesions may result in high-output cardiac failure or hemorrhage. Most infants with systemic involvement present by 2 months of age with respiratory distress, hepatomegaly, a heart murmur, or anemia. The presence of multiple cutaneous hemangiomas should prompt the conduct of a careful history and physical examination. If suspicion exists about visceral involvement, initial screening studies might include a complete blood count, chest radiograph, abdominal ultrasonography, and stool for occult blood. Other potential complications of hemangiomas are presented in Table 129.1.

FIGURE 129.16. A large superficial hemangioma shows whitening of the surface, indicating the start of resolution. |

TABLE 129.1. COMPLICATIONS OF HEMANGIOMAS | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Since most hemangiomas are small and do not threaten vital structures, no therapy is needed. Complicated hemangiomas should be managed in conjunction with a pediatric dermatologist and other specialists as appropriate. Depending on the lesion type and location, therapeutic options include oral prednisone (often at doses of 2 to 4 mg/kg/day) or intralesional corticosteroids. Ulcerated hemangiomas may be treated with pulsed dye laser. Life-threatening lesions (e.g., those associated with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome) may require interferon alfa or other agents.

SKIN LESIONS IN INFANCY, CHILDHOOD, AND ADOLESCENCE

Papules

Skin-Colored

Warts

Warts are among the most common skin lesions affecting children; they also are among the most frustrating, because treating them often is difficult. Warts are caused by infections with human papillomaviruses (HPVs), DNA viruses of which more than 70 different types have been described. HPV types usually can be related to a specific clinical presentation of the wart; for example, types 1, 2, 4, and 7 cause common warts on the hands and feet. Untreated warts generally have a life span of a few months to 5 years or more. Approximately two-thirds disappear within 2 years, but self-inoculation and spread to other persons may occur. Several types of warts are recognized:

Common warts (verrucae vulgaris) are rough skin-colored papules that often are located on the hands. The lesions usually are round, and tiny dark specks frequently can be seen through the surface. These dots represent thrombosed capillaries in the warty tissue. Occasional lesions, particularly those on the face and scalp, may appear as finger-like projections (i.e., filiform warts).

Plantar warts occur on the plantar surface of the foot where pressure forces their growth inward, resulting in deep, painful lesions. Plantar warts may be single or grouped in clusters (i.e., mosaic warts). The black specks of thrombosed capillaries help to distinguish warts from corns, which are localized areas of hyperkeratosis over pressure points.

Flat warts are tiny, flat-topped, skin-colored papules that occur primarily on the face and dorsa of the extremities. Their surface is smooth, and they may number in the hundreds. At times, they seem to form plaques as they coalesce.

Genital warts (condylomata acuminata) tend to be soft, flesh-colored to slightly pigmented papules that may be pedunculated (Fig. 129.17). The occurrence of genital warts in children always should raise the suspicion of sexual abuse. However, in children younger than 2 to 3 years, the condition often results from infection acquired during vaginal delivery.

The response of individual warts to any therapy is variable. Because most warts resolve spontaneously, no intervention is a reasonable choice for some patients. However, parents and older children often desire treatment. For common warts, such keratolytic agents as salicylic and lactic acids in flexible collodion offer painless and effective, albeit slow-acting, therapy. Each day, the warts are soaked in warm water, dried, and

débrided with a pumice stone or an emery board; thereafter, the keratolytic agent is applied. Covering the wart with tape may increase the effectiveness of the treatment. The application of liquid nitrogen or other cryogen is similarly effective but is painful and poorly tolerated by young children. To prevent regrowth of remaining wart tissue, keratolytic therapy should be used in the interval between freezing treatments. Imiquimod, a topical immune response enhancer, also may be effective in the treatment of common warts. The options for treating plantar warts are analogous to those described for common warts. However, a higher potency keratolytic agent may be selected. For resistant warts, cantharidin, a blistering agent, may be applied carefully by the clinician in the office. Alternately, patients may be referred for consideration of immunotherapy, laser therapy, or surgical excision.

débrided with a pumice stone or an emery board; thereafter, the keratolytic agent is applied. Covering the wart with tape may increase the effectiveness of the treatment. The application of liquid nitrogen or other cryogen is similarly effective but is painful and poorly tolerated by young children. To prevent regrowth of remaining wart tissue, keratolytic therapy should be used in the interval between freezing treatments. Imiquimod, a topical immune response enhancer, also may be effective in the treatment of common warts. The options for treating plantar warts are analogous to those described for common warts. However, a higher potency keratolytic agent may be selected. For resistant warts, cantharidin, a blistering agent, may be applied carefully by the clinician in the office. Alternately, patients may be referred for consideration of immunotherapy, laser therapy, or surgical excision.

Options for treating flat warts include topical tretinoin applied daily or the modalities described for managing common warts. Genital warts often respond to the application of podophyllin 25% in tincture of benzoin applied at intervals of 1 to 3 weeks. Patients are advised to remove the medication 4 to 6 hours later by washing. Options for home therapy of these lesions include podofilox and imiquimod. For recalcitrant lesions, laser therapy may be required.

Keratosis Pilaris

Keratosis pilaris is a common, benign skin condition characterized by follicular papules distributed most commonly on the extensor surfaces of the upper arms, thighs, or face. Lesions possess a central plug of keratinaceous material and occasionally have surrounding erythema. They appear most commonly in the second decade of life and, when present on the face, can be mistaken for acne. The cause of keratosis pilaris is unknown but it occurs most often in individuals with atopic dermatitis or ichthyosis vulgaris. For patients who are distressed by the appearance of the lesions, mild keratolytics, such as emollients containing ammonium lactate, urea, or lactic acid, can be used to reduce their prominence. Tretinoin also may prove effective, although it may prove irritating, particularly when used on the face in young children. Patients should be counseled that treatment rarely is completely successful and that lesions may persist.

Id Reaction

Dermatophyte infections, particularly tinea capitis, may induce an immune or “autosensitization” phenomenon called the id reaction. Lesions are numerous, tiny, skin-colored papules (or occasionally vesicles) that are concentrated on the trunk and extremities. The id reaction often appears after systemic antifungal therapy is begun and should not be mistaken for a drug reaction. The presence of papules, vesicles, and other lesions of the palms and fingers may suggest an id reaction caused by tinea pedis. No specific therapy of the id reaction is required.

Lichen Spinulosus

The key clinical feature of lichen spinulosus is round patches of grouped follicular papules, each possessing a spine of keratinaceous material. The lesions are skin-colored or slightly hypopigmented but usually stand out from unaffected skin. They generally are asymptomatic. The lesions may appear in crops relatively rapidly and are found most commonly on the neck, abdomen, buttocks, lateral thighs, and extensor surfaces of the extremities.

The cause of lichen spinulosus is unknown. The histologic picture is one of hair follicles dilated with a keratinaceous plug. Children with atopic dermatitis seem to be most prone to these lesions. The course is variable; the condition may last indefinitely, although affected sites can change over a period of months without therapy. Treatment with a keratolytic agent, such as an emollient containing ammonium lactate or lactic acid, may improve the appearance of lesions.

Syringomas

Syringomas are firm papules that typically appear skin-colored, but may be yellow or brown. They are found most commonly on the lower eyelids and neck, and generally measure 1 to 3 mm. Females are affected twice as frequently as are males, and the lesions appear most often at puberty. Pathologically, the lesions are benign tumors of eccrine glands. Syringomas persist and may increase in number over time. The lesions appear commonly in individuals with Down syndrome. For patients who desire treatment, laser therapy may be effective.

Eruptive Vellus Hair Cysts

Eruptive vellus hair cysts are skin-colored, red-brown or brown-black, 1- to 4-mm, soft, smooth-surfaced papules. The lesions may be scattered or grouped, and typically occur over the anterior chest and extremities. The onset of lesions occurs in the first decade of life. Although lesions usually occur sporadically, an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been documented in some cases. The condition may resolve spontaneously or it may persist, and it usually is asymptomatic. If treatment is desired, tretinoin or lactic acid may be applied topically or individual lesions curetted.

White or Hypopigmented

Molluscum Contagiosum

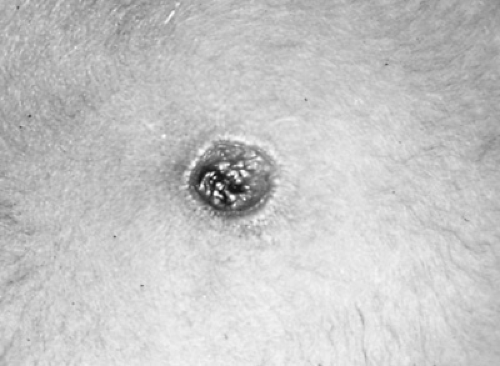

Lesions of molluscum contagiosum, caused by a DNA poxvirus, are described best as pearly papules. Their size may vary from that of a pinhead to more than 1 cm in diameter. The top of the lesion is almost translucent, often revealing a whitish core known as the molluscum body. Larger lesions may have a central umbilication (Fig. 129.18). The number of papules present may vary from few to hundreds. Spread by autoinoculation is common; other members of the family can become infected through contact with the affected person. Individuals with atopic dermatitis are prone to the development of widespread lesions.

Although some physicians recommend no treatment, the condition may last months to years, and parents frequently ask that something be done. In the presence of only a few lesions, in a willing patient, they can be removed with a curet or the surface opened with a needle and the contents expressed. Cantharidin, applied carefully by the clinician in small amounts to each lesion, is painless and effective in causing blistering and extrusion of the central core. Liquid nitrogen, imiquimod, keratolytics, and podophyllin also have been used. Tretinoin also

may be effective, but irritation of surrounding normal skin may preclude its continued use.

may be effective, but irritation of surrounding normal skin may preclude its continued use.

Milia

Milia are discussed in the section Skin Lesions in the Neonatal Period. They commonly are present in newborns but may appear in suture lines, in healed abrasions, at sites of chronic skin erosions in children with epidermolysis bullosa, and at damaged and subsequently healed sites in children with porphyria. Although seldom necessary, incision and expression of the cyst may be performed.

Lichen Nitidus

The tiny (less than 2 mm) papules in lichen nitidus are skin-colored (although they may be hypopigmented in those who are more deeply pigmented) and have a smooth and somewhat shiny surface. The trunk, genitalia, abdomen, and forearms are affected most frequently. Lesions often are numerous and may appear in a linear arrangement at sites of trauma, known as the Koebner phenomenon. The cause is unknown, and the pinhead- to pinpoint-sized lesions have a variable course, lasting months to years. No therapy has been demonstrated to be effective, although the application of a topical corticosteroid may be employed for the minority of patients for whom pruritus is a problem.

Erythematous

Miliaria

Miliaria rubra or prickly heat is a common condition caused by sweat retention. Obstruction in eccrine ducts leads to their rupture with release of sweat into surrounding tissues. Most commonly, this leads to the formation of tiny erythematous papules located in body folds or on the neck and forehead. Miliaria rubra and the related disorders, miliaria crystallina and pustulosa, are discussed in the section, Skin Lesions in the Neonatal Period, earlier.

Angiofibromas

Angiofibromas are hamartomatous papules and nodules composed of fibrous and vascular tissues. They are solid, are pink or skin-colored, and generally appear after the ages of 2 to 3 years, most commonly on the face. Their key significance is their association with tuberous sclerosis, a neurocutaneous, autosomal dominantly inherited disorder with central nervous system and systemic involvement. Sometimes, the lesions are mistaken for acne (Fig. 129.19), but the patient’s age at the time of the lesions’ appearance and the lack of comedones should exclude this diagnosis. Lesions may be treated by dermabrasion or laser therapy.

Papular Urticaria

Papular urticaria is a common, intensely pruritic disorder caused by hypersensitivity to insect bites. New lesions are papules with an erythematous flare that appear in crops (Fig. 129.20). Some lesions have a central punctum that represents the site of the insect’s bite. Others, particularly those that appear in a linear arrangement or cluster, lack a punctum and are believed to be the result of allergens deposited at the time of a bite. Each crop of papules lasts several days but recurrences may be observed at intervals over many months. Most cases occur in the late spring and summer, but household exposure to fleas from animals can cause problems any time of year.

Fleas are the most common cause of papular urticaria, although mosquitos; lice; or grass, grain, or fowl mites also may be responsible. Secondary infections from excoriations are common and, in some children, the wheals may progress to bullae. Treatment success depends on eliminating the biting insects

from the child’s environment and preventing insect bites. Animals should be examined; if infested, they should be treated appropriately and the household environment decontaminated. Established lesions may be treated with an appropriate topical corticosteroid or nonsensitizing anesthetic (e.g., pramoxine), or an oral antihistamine. If outdoor insects are implicated, patients may be advised to wear long sleeves and pants (that may be treated with permethrin to provide additional protection) and to apply an insect repellent to exposed skin. If present, secondary bacterial infection should be treated appropriately.

from the child’s environment and preventing insect bites. Animals should be examined; if infested, they should be treated appropriately and the household environment decontaminated. Established lesions may be treated with an appropriate topical corticosteroid or nonsensitizing anesthetic (e.g., pramoxine), or an oral antihistamine. If outdoor insects are implicated, patients may be advised to wear long sleeves and pants (that may be treated with permethrin to provide additional protection) and to apply an insect repellent to exposed skin. If present, secondary bacterial infection should be treated appropriately.

FIGURE 129.20. Papular urticaria. Resolving hyperpigmented papules and recent, erythematous papules with central puncta from flea bites. |

Gianotti-Crosti Syndrome

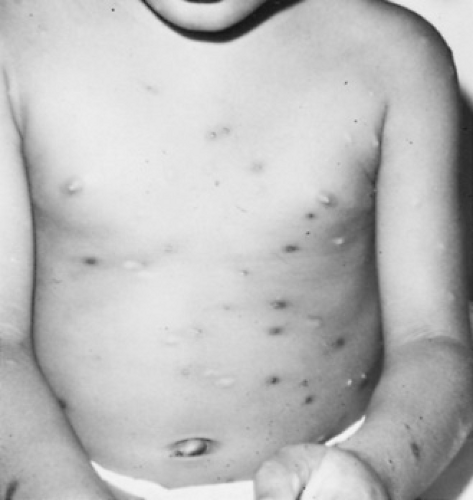

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood, has a distinctive clinical picture because of the predominant location of the erythematous papules on the face, extremities, and buttocks with relative sparing of the trunk (Fig. 129.21). The papules generally measure from 1 to 5 mm in diameter and may appear to be vesicular; they tend to be of similar size, usually appear rapidly, and may be associated with pruritus.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome is believed to be a cutaneous reaction to infection with any of a number of viruses, including hepatitis B, Epstein-Barr virus, parainfluenza virus, coxsackieviruses B and A16, cytomegalovirus, poliovirus, parvovirus B-19, rubella virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and respiratory syncytial virus. It also has occurred following immunizations.

There is no specific treatment for Gianotti-Crosti syndrome; however, the rash resolves within 3 to 8 weeks. If pruritus is severe, a topical corticosteroid or nonsensitizing anesthetic, or oral antihistamine may be prescribed.

Papulosquamous Disorders

Papulosquamous disorders are diseases characterized by elevated, scaling lesions.

FIGURE 129.22. Pityriasis rosea. The diffuse papules may obscure the classic lesions, which are scattered, ovoid pink plaques. |

Pityriasis Rosea

Pityriasis rosea typically produces oval thin plaques composed of tiny papules with a fine scale. At times, particularly in more deeply pigmented patients, papules may be prominent (Fig. 129.22). The cause of pityriasis rosea is unknown but is believed by many to be viral. The disorder occurs most commonly in teenagers and young adults but has been described in infants. Recurrent episodes are uncommon, and small epidemics have been reported among individuals in close contact.

In about one-half of patients, pityriasis rosea begins with the appearance of a herald patch, a solitary erythematous patch, or a minimally elevated plaque. At times, this lesion may be mistaken for tinea corporis. One to two weeks later, the typical generalized eruption begins. The ovoid lesions of pityriasis rosea are concentrated on the trunk and have their long axes parallel to lines of skin stress. Thus, their distribution on the patient’s back gives the appearance of the boughs of a fir tree. Often viewing the rash from across the room facilitates seeing this characteristic pattern. Individual lesions are minimally elevated and erythematous or hyperpigmented. Most lesions are covered by a fine, wrinkled scale (Fig. 129.23). At times, particularly

in more deeply pigmented individuals, lesions may be more papular in appearance or the eruption may involve the extremities and face, sparing the trunk (i.e., inverse pityriasis rosea). Occasionally, the lesions may be urticarial wheals or bullae, or may become purpuric.

in more deeply pigmented individuals, lesions may be more papular in appearance or the eruption may involve the extremities and face, sparing the trunk (i.e., inverse pityriasis rosea). Occasionally, the lesions may be urticarial wheals or bullae, or may become purpuric.

The lengthy course of this disorder should be emphasized to the patient or the parents. The eruption itself develops over a 2-week period, persists for 2 weeks, and then fades over another 2 weeks. This pattern varies greatly, however, and rashes lasting 3 to 4 months are not unusual. Pruritus occurs in up to one-half of patients and may be managed with an emollient containing menthol and phenol, a topical nonsensitizing anesthetic (e.g., pramoxine), or an oral antihistamine. Judicious exposure to sunlight (avoiding burning) may hasten the resolution of the eruption. One report suggested that erythromycin was effective but its results have not been confirmed.

The differential diagnosis of pityriasis rosea includes dry nummular eczema and psoriasis. Secondary syphilis may produce an eruption similar to pityriasis rosea, although patients usually are ill, have lymphadenopathy, and exhibit lesions on the palms and soles. Nevertheless, a serologic test for syphilis should be considered if the patient is sexually active.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is an inherited disorder whose onset occurs before 16 years of age in 25% to 45% of patients. Usually, the lesions are distinctive, with well-demarcated, erythematous papules or plaques covered with a silvery scale (see color Fig. 68.18 in color section). The scale tends to build up in layers, and its removal may cause a bleeding point (Auspitz sign). The papules enlarge to form plaques. Usually, the distribution is symmetric, with plaques commonly appearing over the knees and elbows because they are sites of repeated trauma. Other common sites of involvement are the eyebrows, ears, umbilicus, and gluteal cleft. Frequently, the scalp shows a thick, adherent scale; often, the nails demonstrate punctate stippling or pitting or become discolored and thickened, and the palms and soles may show scaling and fissuring. The Koebner phenomenon (i.e., the appearance of rash at sites of physical, thermal, or mechanical trauma) often is evident.

A variety of inciting factors in addition to trauma have been associated with the appearance of psoriatic lesions. An interesting factor in children is the development of guttate psoriasis, a condition characterized by multiple, small, teardrop-like lesions associated with pharyngeal or perianal Streptococcus pyogenes infection (Fig. 129.24). Other factors implicated are sunburn, drug eruptions, and viral infections. The histologic picture is one of hyperproliferation of the epidermis.

The course of psoriasis is unpredictable. Initial treatment consists of the application of an emollient. Most patients, however, will require therapy with a regimen consisting of an appropriate topical corticosteroid and calcipotriene; topical tar preparations also may be employed. Exposure to sunlight, with care taken not to burn the skin, often is beneficial. Patients with severe, recalcitrant disease may require treatment with an oral psoralen combined with ultraviolet light or methotrexate.

The differential diagnosis in childhood includes such uncommon disorders as pityriasis rubra pilaris, parapsoriasis, and lichen planus. Occasionally, atopic dermatitis may be confused with psoriasis, but psoriasis typically is not pruritic. Pityriasis rosea, tinea corporis, and seborrheic dermatitis also may mimic psoriasis.

Juvenile Dermatomyositis

Scaly, erythematous papules are characteristic of juvenile dermatomyositis. The lesions, called Gottron papules, classically are found over the knuckles, elbows, and knees. A violaceous discoloration of the upper and lower lids (i.e., heliotrope) and malar area and nailfold telangiectases frequently are present.

FIGURE 129.24. The sudden widespread appearance of small, scaly plaques is characteristic of guttate psoriasis. |

Juvenile dermatomyositis may be limited to the skin (i.e., amyopathic dermatomyositis, dermatomyositis sine myositis) or be associated with symmetrical muscle pain and proximal muscle weakness. Evaluation of patients suspected of having juvenile dermatomyositis should include measurement of muscle enzymes, including creatine kinase, aldolase, aspartate aminotransferase, and lactic dehydrogenase. Occasionally, muscle biopsy, electromyography, or magnetic resonance imaging is required. Systemic corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy, although topical corticosteroids or hydroxychloroquine may be used to control skin disease.

Lupus Erythematosus

A wide variety of rashes have been associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The so-called butterfly rash, a slightly raised, erythematous or violaceous thin plaque or patch with fine scale located over the malar areas and bridge of the nose, is most often associated with SLE. Patients may also exhibit discoid lesions, round, well-demarcated, erythematous to violaceous plaques with fine telangiectases, an adherent scale, and areas of atrophy. The lesions appear most commonly on the face and scalp and in the ears. Other cutaneous lesions include transient erythematous annular lesions in sun-exposed areas (subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus), red or purple nodules, scaling patches on the dorsa of the fingers, and scarring and nonscarring alopecia.

Lichen Planus

The papules in lichen planus, a disorder found mostly in adults, characteristically are polygonal. When the lesions are examined closely, the flat-topped papules seem to form rectangles, squares, and other shapes (Fig. 129.25). The classic lesions are violaceous and occur most frequently on the wrists and

extensor surfaces of the forearms. They may coalesce to form plaques. Significant scaling of the lesions may occur on the lower extremities. Oral lesions, consisting of tiny white papules in lacy patterns, may occur on the buccal mucosa. Nail dystrophy, including roughening of the nail surface or longitudinal ridging, is not common in children with lichen planus.

extensor surfaces of the forearms. They may coalesce to form plaques. Significant scaling of the lesions may occur on the lower extremities. Oral lesions, consisting of tiny white papules in lacy patterns, may occur on the buccal mucosa. Nail dystrophy, including roughening of the nail surface or longitudinal ridging, is not common in children with lichen planus.

FIGURE 129.25. The classic papules of lichen planus are not only flat-topped but also purple and polygonal. (Courtesy of Alan B. Fleischer, Jr., MD.) |

Lichen planus is intensely pruritic. Excoriations can lead to secondary infection and to the occurrence of lesions at sites of trauma. The cause of the eruption is unknown, and the lesions persist for 8 to 18 months. Therapy consists of the application of a moderate- to super-potent corticosteroid and the administration of an antihistamine to control pruritus. In severe or unresponsive cases, oral corticosteroids or retinoids may be indicated.

Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is an uncommon disorder of unknown cause characterized by erythematous, scaly papules that may coalesce to form plaques. The papules are centered about follicles and have tapered tips. A characteristic feature is the presence of islands of normal tissue between the joined plaques. Patients also develop thick, adherent scale on the scalp (similar to that seen in psoriasis) and thickening of the palms and soles, which may be marked. The degree of skin involvement varies widely. Pruritus is absent or minimal. Most cases of pityriasis rubra pilaris occur sporadically but familial clustering has been observed.

The course of pityriasis rubra pilaris usually is prolonged, interspersed by remissions and exacerbations. For patients with mild forms of the disease, topical agents, including emollients, keratolytics, tretinoin, or corticosteroids, may be beneficial. Oral retinoids and other systemic therapies are required for those with severe disease.

Pityriasis Lichenoides

Pityriasis lichenoides is an uncommon disorder with two variants: an acute form (known as pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta [PLEVA]) and a chronic type (known as pityriasis lichenoides chronica). Both produce a generalized erythematous papular and macular eruption, usually over the trunk and extremities. The lesions persist for months or recur in periodic eruptions. The acute form produces lesions that may be hemorrhagic, vesicular, pustular, or even necrotic. Initially, the eruption may be mistaken for varicella. The chronic form is characterized by reddish brown papules that have an adherent scale and range from a few millimeters to 1 cm in diameter. The wafer-like plaques may be confused with pityriasis rosea. The cause of pityriasis lichenoides is unknown. Some cases resolve with exposure to ultraviolet light; others improve with prolonged erythromycin therapy.

Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus, a self-limited eruption most common in children, is characterized by the rapid development of multiple small papules arranged in a linear, band-like pattern over an extremity (Fig. 129.26). The bands may be 1 to several centimeters in width, irregular or fairly uniform, and continuous or interrupted; they occur most commonly on the lower extremities. The papules may be scaly and generally are skin-colored or erythematous, although in deeply pigmented individuals they may be hypopigmented. The cause of this distinctive lesion is unknown. It has a duration of a few weeks to as long as 3 years. As resolution begins, papules disappear, leaving hypopigmentation that may persist for several months. Topical corticosteroids and keratolytics may hasten its resolution. Linear epidermal nevi, linear psoriasis, and linear lichen planus are included in the differential diagnosis.

Nodules

Erythematous

Pyogenic Granulomas

Pyogenic granulomas are benign vascular proliferations precipitated by trauma or infection, although the mechanism for growth stimulation is not known. The lesions grow rapidly, may be papular or nodular, and often are pedunculated. They usually are solitary and dark red to purple, with a surface that generally is moist, crusted, or eroded and that may bleed easily when traumatized (Fig. 129.27).

The differential diagnosis of pyogenic granuloma includes warts, molluscum contagiosum, and superficial hemangiomas. The best treatment is excision and electrodesiccation of the base, although pulsed dye laser may be employed.

Erythema Nodosum

Erythema nodosum presents usually as painful, erythematous, warm nodules with indistinct borders most often located on the pretibial surfaces (Fig. 129.28). The number of nodules may vary from one to many. Their bright-red color changes in a few days to brown-red or purple and later to yellow-green, as seen with a bruise. Lesions may occur on other body sites, including the arms and face. Erythema nodosum represents a hypersensitivity reaction to various infections, drugs, and other conditions. It is a form of panniculitis, an inflammation of the subcutaneous fat.

FIGURE 129.28. Erythema nodosum. Tender erythematous nodules over the pretibial surface. See Color Figure 129.28 in color section. |

The most common precipitating agent in erythema nodosum in children in the United States is a preceding streptococcal infection. In the past, tuberculosis was the foremost cause. Other, less common precipitants include infection with Epstein-Barr virus or Yersinia enterocolitica, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and leptospirosis. An association with inflammatory bowel disease and sarcoidosis has been noted. Drugs most frequently incriminated include sulfonamides, diphenylhydantoin, and oral contraceptive agents. Chronic or recurrent episodes suggest more serious systemic disorders, such as a collagen vascular disease, lymphoma, or inflammatory bowel disease. In many cases, however, a trigger is not found.

The lesions of erythema nodosum initially may be confused with areas of cellulitis, insect bites, or bruises. Arthralgias occur in some cases, and arthritis may be present, suggesting rheumatic disorders. Biopsy samples of lesions reveal intense inflammation in the subcutaneous fat, including around vessels. If a precipitating factor is identified, it should be managed appropriately. Most patients respond to relative rest and an oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agent. Typically, erythema nodosum resolves in 2 to 3 weeks.

Panniculitis

The term panniculitis denotes inflammation of the subcutaneous fat. The blood vessels usually are affected also, with resultant fat necrosis. The clinical appearance commonly is one of erythematous, enlarging nodules that frequently are painful to palpation. The lesion size may vary considerably, from less than 1 cm to many centimeters in diameter. As the lesions subside, the overlying skin becomes less erythematous, eventually leaving macular areas of hyperpigmentation. With resolution, a depression in the overlying skin is common.

The causes of panniculitis vary. Cold-exposure panniculitis is common on infants’ cheeks. Some cases are associated with connective tissue diseases, particularly lupus erythematosus. Weber-Christian disease features recurring inflammatory subcutaneous nodules with systemic symptoms, particularly fever. The withdrawal of corticosteroids also may result in the appearance of panniculitis.

Skin-Colored

Epidermal Cysts

Most epidermal cysts occur after puberty. Clinically, they appear as discrete, enlarging, raised, somewhat compressible nodules of variable size. The overlying skin is normal, although a dilated follicular orifice that communicates with the underlying cyst may be appreciated. If the cyst ruptures, the lesion will become painful and erythematous. Epidermal cysts occur most frequently on the face, scalp, and back. Rarely, they may be associated with Gardner syndrome, other features of which include polyposis of the gastrointestinal tract, particularly the colon, multiple osteomas, and cutaneous fibromas. If treatment of an epidermal cyst is desired, excision is preferred.

Lipomas

The subcutaneous tumors typical of lipomas are spongy and often are lobulated. They occur most frequently in the subcutaneous tissue of the back and abdominal wall. The overlying skin is unaffected and not attached to these lesions, which are nontender and slow-growing and may be solitary or multiple. No therapy is required but lesions may be excised. Lesions in the midline lumbosacral area should be evaluated for underlying spinal dysraphism.

Granuloma Annulare

Granuloma annulare, a benign, self-limited disorder, produces small nodules within the dermis. Individual nodules enlarge to form ring-like lesions with a clearing center and an elevated, papular border (Fig. 129.29). Lesions are asymptomatic, skin-colored or violaceous, and usually are located on the hands, feet, or ankles. Occasionally, granuloma annulare produces papules located on the hands or fingers (papular granuloma annulare) or nodules overlying the pretibial surfaces (subcutaneous granuloma annulare). The cause of granuloma annulare is unknown. Biopsy reveals focal degeneration of collagen within the dermis with reactive inflammation.

The lesions of granuloma annulare resolve over months to years; approximately 75% of lesions disappear within 2 years. No therapy is required, but if it is desired options include the use of a topical or intralesional corticosteroid or cryotherapy. Because of its ring-like appearance, granuloma annulare often is mistaken for tinea corporis. However, the firm border and absence of scale should suggest the diagnosis.

Pilomatricomas

Pilomatricomas are firm to hard, multilobulated, slow-growing tumors. Most are skin-colored, but some may be reddish or bluish. They occur most commonly on the head and neck and almost always are solitary. Pilomatricomas are benign but often are removed for cosmetic reasons. They occur most commonly in the first two decades of life.

Connective Tissue Nevi

Connective tissue nevi are firm, skin-colored papules, nodules, or plaques. They often are grouped together, creating an orange peel appearance. Connective tissue nevi represent localized collections of dermal collagen and elastic tissue. Most often, lesions represent isolated cutaneous findings but they may be associated with tuberous sclerosis (i.e., the shagreen patch) or other syndromes.

Dermatofibromas

Dermatofibromas are solitary, hard, well-defined, dome-shaped nodules that occur occasionally in children. They are fixed firmly to the skin, and their color varies from skin-colored to red-brown to tan or black. Lesions rarely exceed 2 cm in diameter. Applying lateral pressure to the lesion causes dimpling of its surface. Dermatofibromas may arise spontaneously or following trauma such as an insect bite. No therapy is necessary and lesions will persist.

Neurofibromas

Neurofibromas are skin-colored or brown nodules that when depressed may be reduced temporarily as if through a button hole. They represent benign tumors of Schwann cells. Larger lesions that feel like a “bag of worms” on palpation are termed plexiform neurofibromas. Although they may occur as an isolated phenomenon, neurofibromas are one diagnostic feature of neurofibromatosis type 1. In those who have neurofibromatosis type 1, neurofibromas typically do not appear until after the first decade.

Hyperpigmented

Mastocytosis

Mastocytosis represents a spectrum of disorders characterized by excessive numbers of mast cells in the dermis and, occasionally, other organs (e.g., bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract) and the symptoms produced by the elaboration of mediators derived from these cells. In some cases, the disorder is caused by mutations in the c-KIT gene that result in an abnormal proliferation of mast cells.

Mastocytosis can be categorized into cutaneous and systemic forms. The most common type, particularly in children, is cutaneous mastocytosis, in which mast cell accumulation is limited to the skin. Four types of cutaneous disease are recognized: urticaria pigmentosa (UP), solitary mastocytomas, diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis, and telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans (TMEP). The most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis is UP, accounting for 70% to 90% of all cases. Lesions typically appear during the first year of life and increase in number, although they may be present at birth. They are small, red-brown, tan, or yellow macules or minimally elevated plaques that possess an orange peel appearance (Fig. 129.30). Approximately 10% to 20% of children with cutaneous mastocytosis have solitary mastocytomas, single or as many as five macules or thin plaques. They are larger than

the lesions of UP but have a similar time of onset, color, and appearance (Fig. 129.31). Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis and TMEP occur rarely in children. The former variant appears in the neonatal period and is characterized by widespread infiltration of the skin with mast cells; discrete lesions are absent but the skin is thickened with numerous tiny papules. TMEP produces hyperpigmented macules and telangiectasias.

the lesions of UP but have a similar time of onset, color, and appearance (Fig. 129.31). Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis and TMEP occur rarely in children. The former variant appears in the neonatal period and is characterized by widespread infiltration of the skin with mast cells; discrete lesions are absent but the skin is thickened with numerous tiny papules. TMEP produces hyperpigmented macules and telangiectasias.