18 Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology

Pediatricians and other primary care providers frequently encounter children and adolescents with gynecologic concerns. Patients seek care for prepubertal vulvovaginitis, vaginal discharge, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), menstrual disorders such as dysmenorrhea and abnormal uterine bleeding, as well as other, less common diagnoses. As primary care providers increase their understanding of pediatric gynecology and adolescent medicine, a girl’s first gynecologic evaluation may not require a visit to a gynecologist. Accordingly, this chapter emphasizes normal anatomy, techniques of examination, and the conditions most commonly encountered in primary care. Complementary information can be found in Chapter 6 (Child Abuse and Neglect, including detailed illustrations and definitions of genital anatomy, and additional photos of normal and abnormal genital anatomy) and in Chapter 9 (Endocrinology; illustrating Tanner staging and discussing normal, delayed, and precocious pubertal development).

Normal Female Genitalia

Newborn and Prepubertal

In the newborn girl the physical appearance of the genitalia reflects stimulation by maternal sex hormones (Fig. 18-1). Separation of the labia minora reveals thick, redundant hymenal folds that often hide the small central vaginal opening and urethral meatus. The mucosa is moist, vaginal pH is acidic, and a milky discharge (physiologic leukorrhea) is often seen. Vaginal bleeding during the first week of life is common. It is caused by withdrawal of maternal estrogen after delivery, and parents can be reassured that this is normal. Breast development, with palpable breast tissue, engorgement, and less commonly a clear or cloudy discharge, is observed in full-term neonates of both genders (see Chapter 2). Without ongoing stimulation from maternal estrogen, these findings gradually subside over several months. During this period, infants are at increased risk for developing breast inflammation and infection (see Chapter 12). Local trauma, including squeezing, may increase the likelihood of infection.

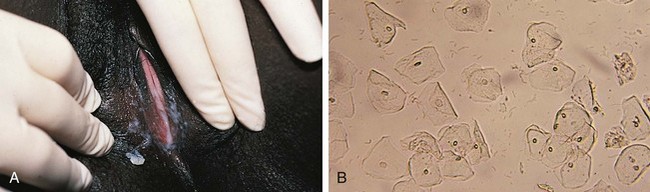

Similarly, the effect of maternal hormones on the female genitalia gradually disappears; the labia majora lose their fullness, and the labia minora and hymen become thinner and flatter. Separation of the labia minora usually exposes the vaginal opening (Fig. 18-2, A and B). As the young infant matures, the labia cover less of the vaginal vestibule, particularly when the infant or child is sitting, and thus offer incomplete protection from external sources of irritation. The mucosa has a glistening, reddish pink hue that on first inspection sometimes is mistaken for inflammation by observers unaccustomed to examining prepubertal genitalia. Vaginal pH is now neutral or alkaline, and secretions are minimal.

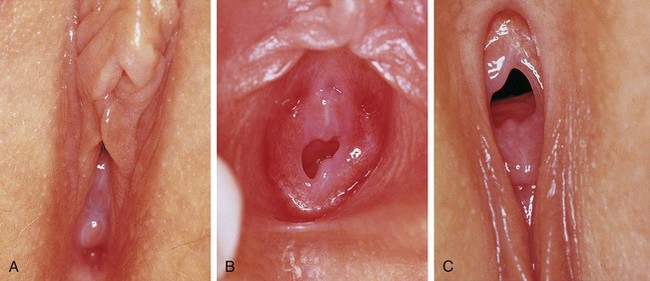

Physiologic changes also cause variations in the appearance of the hymenal tissues during childhood. During early infancy the tissues are relatively thick and can be redundant into the second year (Fig. 18-3, A and B). Usually in the first months of life, the hymen becomes thin and translucent, with smooth edges (Fig. 18-2, A and B and Fig. 18-3, C-E). When the child enters puberty, the hymen again thickens under the influence of estrogen.

Figure 18-3 Normal variations in hymenal configuration. A, In this young infant, the redundant hymen totally obscures the vaginal orifice. B, In a 23-month-old the hymenal folds are redundant and the central orifice is visible. C, Annular orifice of a 2-year-old. Note the thin sharp edges of the hymenal membrane. D, Crescentic hymenal orifice. E, Crescentic orifice with septal remnants at 1 and 5 o’clock. F and G, Two variations of a septate hymen are seen, one in an infant and another in an older child. See also Fig. 18-7.

(A and B, Courtesy Janet Squires, MD, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pa.; C, courtesy John McCann, MD, University of California at Davis, Davis, Calif.; D, E, and G, courtesy Pat Bruno, MD, Sunbury Community Hospital Center for Child Protection, Sunbury, Pa.; F, courtesy Carol Byers, CRNP, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pa.)

The shape of the vaginal orifice also varies. Annular (Fig. 18-3, C), crescentic (Fig. 18-3, D and E), and fimbriated (with fingerlike projections around the hymenal rim) hymens are all normal variations. Other irregular shapes occur, such as a teardrop, for example, with the narrow portion formed by an anterior notch to one side of the clitoris. On rare occasions there is a completely imperforate hymen; more commonly there is a septated hymen (Fig 18-3, F and G), or a fenestrated hymen with small perforations is seen.

From about 6 to 8 weeks of age until puberty the perineum, perivaginal tissues, and pelvic supporting structures are relatively rigid and inelastic. This factor increases the likelihood of tearing as a result of trauma. In addition, before the onset of puberty, the ovaries are positioned above the pelvic brim (Table 18-1). This intraabdominal location accounts for the fact that ovarian disorders in childhood frequently present with abdominal, rather than pelvic, signs and symptoms.

Pubertal

Girls whose labia minora protrude beyond the labia majora (Figure 18-4 often wonder if their genital appearance is normal. There is no consensus on the diagnostic criteria for labial hypertrophy, but normally the maximal width between the midline and lateral free edge of the labia minora should measure less than 3 to 5 cm. Patients with labial hypertrophy may present with pain, irritation, chronic infection, problems with personal hygiene (e.g., during menses), or problems during sports or sexual activity. Most symptoms can be alleviated by addressing personal hygiene and appropriate choice of clothing to minimize friction. Sometimes use of an antichafe product can help to prevent abrasions. Referral to a surgeon experienced in labioplasty may be considered for a mature, fully developed patient whose symptoms do not respond to conservative management. However, patients should be counseled that surgery can result in scarring, chronic vulvar pain, and dyspareunia. In most cases, reassurance and discussion of the variations in normal anatomy are all that is required.

Figure 18-4 Eleven-year-old patient with hypertrophy of the left labium minus.

(Reprinted with permission from Pardo J, Sola V, Ricci P, et al: Laser labioplasty of labia minora, Int J Gynaecol Obstet 93:38-43, 2006.)

Other normal changes during puberty include slight enlargement of the clitoris and increased prominence of the estrogen-responsive urethral mucosa. The hymen also thickens and its central orifice enlarges. The vaginal mucosa thickens and softens and becomes moist and pink as secretions increase and pH levels drop. Perineal and pelvic tissues become more elastic, and the ovaries gradually descend into the pelvis. In the months preceding menarche, physiologic leukorrhea increases and becomes noticeable. It consists of a white discharge containing mature epithelial cells and vaginal secretions stimulated by estrogen (Fig. 18-5). In some girls the unopposed estrogen secretion of puberty stimulates leukorrhea so profuse that it becomes concerning and irritating because the perineum is constantly moist.

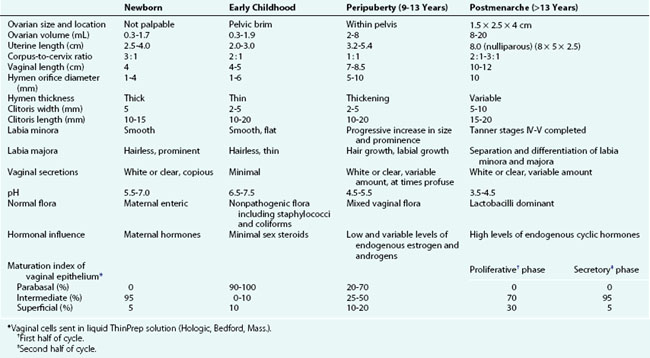

The developmental aspects of gynecologic anatomy and physiology are summarized in Table 18-1. There is variation in the range of normal reproductive organ size as seen on ultrasound. Some authors (Garel et al, 2001) have proposed the following as upper values for prepubertal girls: uterine length, 4.5 cm; uterine thickness, 1 cm; and ovarian volume, 4 to 5 mL. The Tanner stages of pubertal development are presented in Chapter 9.

Gynecologic Evaluation

Examination of the Prepubertal Patient

Technique

Young infants can be assessed easily on an examination table after being positioned by the examiner. An older infant, toddler, or preschool child tends to be more relaxed when examined on her mother’s lap, with the mother assisting by gently holding the child in either the frog-leg or lithotomy position (Fig. 18-6). School-age children usually can be examined on the table in the frog-leg, lithotomy, or knee–chest position (see Chapter 6). Knee–chest positioning can provide excellent visualization of the hymen and the distal vagina (Fig. 18-7, C), but proper positioning can be challenging; some patients may feel threatened by being examined from behind. An alternative means of achieving visualization of the distal vagina is with the patient supine and performing the Valsalva maneuver (i.e., asking the child to push down as if she were going to pass a stool). This often produces distention of the distal vagina and hymenal orifice, facilitating visualization and atraumatic collection of specimens.

Figure 18-7 Perineal visualization in various positions and with various techniques of parting the labia (see also Figure 18-2, A and B). A-C, Views of the same child taken on the same day and clearly showing the variations in appearance when using different positions and different techniques to facilitate visualization of the introitus and lower third of the vagina. A, Supine frog-leg position. B, Supine frog-leg position using labial traction. C, knee–chest position.

(A-C, Courtesy Mary Carrasco, MD, Mercy Hospital, Pittsburgh, Pa.)

Once the patient is properly positioned, visualization of the introitus, hymen, and lower portion of the vagina is facilitated by maneuvers that separate the labia. These maneuvers should be explained first and the child reassured that the examiner is just going to look. If the patient desires or is mildly anxious, she may place her hands beneath the examiner’s, or the mother may be enlisted to perform the maneuver. Some girls prefer to separate their labia themselves. The maneuvers include labial separation (see Fig. 18-2, B), and labial traction (see Figs. 18-2, A and 18-7, B). When using a hand-held light (otoscope) a second set of hands (parent or nurse) may be needed to maximize labial separation and focus the light. Care must be taken to ensure that excess traction is not applied during these maneuvers because it can result in painful tearing of labial adhesions, if present.

Specimen Collection

To collect specimens of vaginal secretions for culture, wet mounts, or to evaluate the maturation index of vaginal epithelial cells (see Table 18-1), the Dacron wire swab should be premoistened with sterile nonbacteriostatic saline. Before starting, it is often helpful to allow the patient to handle a moistened swab and touch herself with it. The swab is inserted gently through the vaginal opening, taking care to avoid contact with the hymen, which is exquisitely sensitive. This is most easily accomplished with the patient in the knee–chest position or with use of the Valsalva maneuver. However, if collection is likely to be difficult because of pain or anxiety or because the hymenal orifice is very small, application of a topical anesthetic to the perineal and hymenal area beforehand can be beneficial. Although topical lidocaine preparations work within 5 to 10 minutes, they can produce transient discomfort before the onset of anesthetic action, reducing cooperation in some patients. When time permits, use of a newer topical anesthetic cream (e.g., EMLA or LMX) is an excellent alternative. Dry cotton-tipped swabs should be avoided because they tend to abrade the thin vaginal mucosa of the prepubertal child. Table 18-2 lists the specimens that may be considered in evaluating patients with symptoms of vulvitis, vaginitis, or vaginal discharge.

Table 18-2 Laboratory Investigations for the Evaluation of Gynecologic Complaints

| Laboratory Study/Specimen | Diagnostic Utility |

|---|---|

| Saline wet mount | Inflammatory cells, yeast, trichomonads, clue cells, lactobacilli, mature and immature epithelial cells, sperm |

| KOH | Yeast, “whiff test” for bacterial vaginosis (also can be positive with Trichomonas) |

| Vaginal pH | Elevated in bacterial vaginosis (also can be elevated with Trichomonas). Obtain from lateral or anterior vaginal wall, not from pooled secretions or saline-diluted specimen |

| Vaginal specimens | Routine culture (Amies medium without charcoal) for nonvenereal pathogens |

| Culture for enteric bacteria including Shigella (Cary-Blair medium) | |

| Culture for gonorrhea,* Trichomonas, Chlamydia (if forensic evidence needed) | |

| NAAT for gonorrhea, Trichomonas, Chlamydia | |

| Cervical specimens | Culture for gonorrhea* or Chlamydia (for forensic evidence); NAAT for gonorrhea or Chlamydia |

| Pap smear/ThinPrep | Squamous intraepithelial lesions; consequences of HPV including precancerous and cancerous lesions; cell maturation index (estrogenization) |

| Genital ulcer/lesion specimen | HSV culture (if suspect chancroid use moistened swab at base of lesion and transport as rapidly as possible in Amies medium without charcoal; send to reference laboratory to test for Haemophilus ducreyi) |

| Biopsy | Dysplastic, atrophic, or unusual lesions of vulva, vagina, and cervix |

| Urine specimen | Urinalysis; urine culture; gonorrhea, or Chlamydia NAAT |

| Perianal specimen | Pinworms and eggs: Parent obtains sample during night (or first thing in morning before patient bathes) by pressing firmly over anal area with a pinworm paddle (optically clear polystyrene paddle connected to cap of a transport container) or a 1-inch strip of cellophane tape (which is then affixed to a glass slide) |

| Serologic tests | Syphilis (RPR and Treponema-specific testing), HIV |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; RPR, rapid plasma reagin.

* Use Amies medium with charcoal.

Examination of the Pubertal Patient

Indications

A gynecologic examination should be considered for any patient with a variety of specific complaints and concerns, including those listed in Box 18-1. This examination should include careful inspection of the external genitalia and regional lymph nodes, and palpation of the uterus and adnexa when indicated. In some cases precise assessment of internal pelvic structures may require radiologic imaging. For example, during puberty, if menarche is delayed or menstrual periods are unusually problematic (e.g., excessive pain, unusually irregular flow patterns), ultrasound evaluation can be useful.

Box 18-1 Indications for Gynecologic Examination in Pubertal Patient

STD, sexually transmitted disease.

Use of a speculum is typically not required but is useful in situations that necessitate visual inspection of the vaginal cavity or cervix, including those listed in Box 18-2. Furthermore, the gynecologic examination is an important part of routine health care for sexually active adolescent girls (Box 18-3), and should be considered at 6-month intervals with greater or lesser frequency depending on behavioral risk factors. In the absence of the above indications, a speculum could first be considered at age 21 years. At this age women should undergo their first cervical cytology screening, using liquid-based cytology or traditional Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, according to recommendations from the Committee on Adolescent Health Care of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG, 2010).

Box 18-2 Indications for Use of a Speculum during Gynecologic Examination

Pap smear (patients over 21 yr old; earlier in sexually active immune-compromised patients)

Persistent unexplained bleeding

Suspected anatomic abnormality (e.g., vaginal septum, duplicated cervix)

Box 18-3 Routine Screening for the Sexually Active Adolescent*

External Genital Examination and Bimanual Examination

Every 6-12 mo and to evaluate symptoms or exposure to a new partner

Specific Testing for GC, CT, HIV, and Syphilis

Every 6-12 mo and to evaluate symptoms or exposure to a new partner

Wet Mount with KOH Preparation and Vaginal pH

Every 6-12 mo and to evaluate symptoms or exposure to a new partner

Technique

A thorough and directed history precedes the examination. A comprehensive outline is suggested in Table 18-3. Adequate time should be devoted to interviewing the patient alone, which provides an opportunity to ask questions about voluntary and involuntary sexual activity and to explore other concerns that may be difficult to discuss in the presence of a parent. A similar opportunity should be given to the parents to express any particular concerns or worries that they have been reluctant to share in their daughter’s presence.

Table 18-3 Complete History of an Adolescent with Gynecologic Concerns

| Category of Information | Specific Information Required |

|---|---|

| General | |

| Home | Who lives there and quality of relationships; sources of conflict and support |

| Education/employment | School, grades, curriculum, repeated grades, goals, behavioral or learning difficulties; if working—type, occupational hazards, hours, literacy/numeracy |

| Activities | Exercise, nutritional content (specifically calcium, iron, fat, fiber, folate), body image, eating behaviors/patterns, peer activities, friends, hobbies |

| Drugs | Caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, crack, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, pills, injectable drugs; rehabilitation or treatment history |

| Suicide | Depression, anxiety, psychiatric treatment, medications, major losses or disruptions, counseling history |

| Abuse/exploitation | Physical, sexual, or emotional; family, relationship, peer, school, and community violence or exploitation |

| Obstetric and Gynecologic History | |

| Menstrual | Menarche (age); cycles (length, duration, quantity of flow, use of pads or tampons); first day of last menstrual period; dysmenorrhea and associated disability; premenstrual symptoms (PMS); abnormal bleeding; mid-cycle pain (mittelschmerz) and spotting; douching; feminine hygiene product use (including scented products and deodorants) |

| STI | Herpes, gonorrhea, Chlamydia, syphilis, PID, pubic lice (“crabs”), HPV (venereal warts), Trichomonas, HIV, hepatitis A, B, and C, undiagnosed pelvic pain |

| Pap | Abnormal results, colposcopy, biopsies, treatments, follow-up |

| Urologic | Urinary tract infection or kidney problems, enuresis, incontinence, dysuria, urgency, frequency |

| Vaginal discharge | Color, odor, quantity, duration, pruritus |

| Vaginal infections | Yeast, bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis |

| Obstetric | Previous pregnancies and outcomes, fertility plans and concerns |

| Sexual | Last and other recent intercourse and protection; specific HIV risk to self and partners; sexual experience and age at onset; sexual practices, condom use; gender of partners, sexual orientation; number of partners, lifetime and recent; satisfaction with sexual experience; sexual problems with self or partner |

| Contraceptive | Current and past methods, satisfaction, consistency of use, problems |

| Past Medical History | Prior sources of care (routine, episodic, and emergency); immunization status including hepatitis A and B and HPV; rubella and varicella status; hypertension; migraines with aura or neurologic signs; thromboembolic events |

| Medications/Treatment | History of self-treatment with over-the-counter or prescription medications, and any integrative therapies or medications |

| Family History | Thromboembolic events at an early age or associated with pregnancy or with hormonal contraceptives; disease or death caused by alcohol, drugs, tobacco; gynecologic or obstetric problems; age at childbearing; endocrine problems (especially thyroid); bleeding problems (especially OB/GYN-related bleeding, mucus membrane bleeding, or need for blood transfusion); congenital malformations; mental retardation; reproductive loss |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; PMS, premenstrual syndrome; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

The pelvic examination is done after other components of the physical examination. The patient should empty her bladder beforehand, and a urine specimen can be collected at this time if needed for testing. Raising the head of the examining table 20 to 45 degrees helps relax abdominal muscles and facilitates maintenance of visual contact with the patient. She is then assisted into the lithotomy position at the end of the examination table. During the examination, the examiner should talk to the patient to explain what she or he is seeing and to provide reassurance and education. Maintaining a dialogue throughout the procedure also usually helps the patient relax. Conversation can confirm normal anatomic findings and provide the patient with examples of a correct and comfortable vocabulary describing her reproductive anatomy and function. A hand mirror held by the patient is often useful for similar reasons. Before beginning, the examiner should carefully explain the various parts of the examination: inspection of the external genitalia, speculum examination of the vagina and cervix (with specimen collection), and bimanual palpation. Use of anatomic drawings and/or models can be helpful and educational (Fig. 18-8). Gloves should be worn for both external and internal examinations.

Figure 18-8 Anatomic drawings are useful for education and to prepare adolescent patients for gynecologic examination.

If a speculum examination is required, successful examination depends on adequate patient preparation and use of appropriate instruments. For virginal adolescents, the narrow-bladed Huffman speculum ( ×

×  inches) is recommended. Although long enough to expose the cervix, its narrow blades are usually inserted easily through the virginal introitus. Most sexually active adolescents can be examined with the straight-sided Pederson speculum (

inches) is recommended. Although long enough to expose the cervix, its narrow blades are usually inserted easily through the virginal introitus. Most sexually active adolescents can be examined with the straight-sided Pederson speculum ( × 4 inches); however, the Huffman speculum should be considered as an alternative for a first pelvic examination or for particularly anxious patients. The duck-billed Graves speculum (

× 4 inches); however, the Huffman speculum should be considered as an alternative for a first pelvic examination or for particularly anxious patients. The duck-billed Graves speculum ( ×

×  inches) is useful in parous patients (Fig. 18-9). Obese patients may require a Graves speculum or a longer Pederson (1 ×

inches) is useful in parous patients (Fig. 18-9). Obese patients may require a Graves speculum or a longer Pederson (1 ×  inches) for adequate visualization of the cervix. Metal speculums are preferred because they are easier to manipulate and are available in a greater range of lengths and widths. If only a single size of disposable plastic speculum is routinely used at a facility, it is important to have a backup supply of smaller metal speculums.

inches) for adequate visualization of the cervix. Metal speculums are preferred because they are easier to manipulate and are available in a greater range of lengths and widths. If only a single size of disposable plastic speculum is routinely used at a facility, it is important to have a backup supply of smaller metal speculums.

The examiner may then gently insert the index finger into the vagina to assess the size of the introital opening and to locate the cervix. Vaginal muscle tone can be assessed by asking the patient to “tighten her muscles” around the examiner’s finger. Conscious relaxation can be practiced by asking the patient to relax those same muscles and to push her buttocks onto the examining table. Both plastic and metal speculums should be moistened with warm water to increase comfort and ease of insertion. With the index finger partially withdrawn but gently pressing on the vaginal floor, the speculum is inserted over the finger into the vagina, taking care to avoid catching pubic hairs or the labia in the mechanism of the speculum. This is done at an oblique angle along the posterior wall to accommodate the vertical introitus and avoid traumatizing the urethra, which lies above the anterior vaginal wall. Another technique that effectively assists insertion involves using the middle and index fingers to stretch the posterior labial folds down and out before inserting the speculum. With the speculum in place the vaginal walls are inspected for erythema, lesions, and quality and quantity of discharge, and specimens are collected (see Specimen Collection, below).

Once the examination is completed, the patient should be helped out of the lithotomy position, given tissues to wipe away any lubricant or discharge, and allowed privacy to get dressed. At the conclusion of the visit the examiner can present the results of any office-based testing (such as microscopic evaluation of wet mount and KOH preparation). The use of handouts, printed pictures, or line drawings can enhance the patient’s understanding of the results (see Fig. 18-8). This is also an opportunity to encourage communication between the young woman and her parent, as appropriate to the circumstance.

Specimen Collection

If a speculum examination is required (see Box 18-2), the vaginal pH level is measured by holding pH paper (described previously) against the lateral vaginal wall, away from pooled secretions. Visible vaginal secretions from the posterior vaginal pool should be obtained with a cotton or Dacron swab for wet mount. Before obtaining samples from the cervix, any surface mucus should be gently removed with cotton swabs. Purulent secretions (mucopus) typically turn the swab yellow and may be saved for microscopic examination. The normal nulliparous cervix usually has a small round os (Fig. 18-10). Any cervical lesions seen, such as cysts, warts, polyps, or vesicles, should be noted. An ectropion (or eversion) of the endocervical columnar epithelium onto the cervical surface is common and normal in adolescents (Fig. 18-11). Ectropion should be distinguished from cervicitis, the latter being suggested by erythema, friability, and/or mucopurulent cervical discharge (see Fig. 18-41, A).

Genital Tract Obstruction

Labial Adhesions

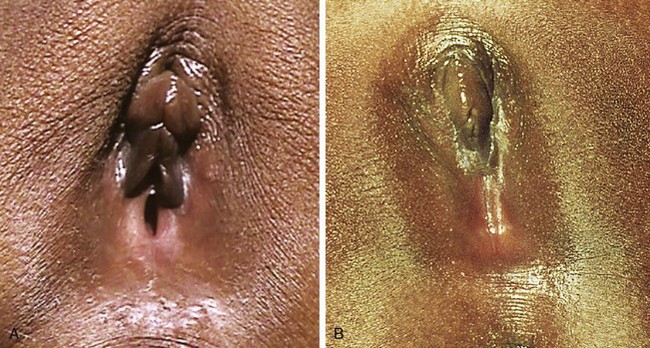

The most common form of “vaginal obstruction” in prepubertal patients is really a pseudo-obstruction or partial obstruction produced by “fusion” of the labia minora as a result of labial adhesions. On inspection the clinician finds a smooth, flat membrane with a thin lucent central line overlying the introitus. It is postulated that inflammation and erosion of the superficial layers of the mucosa—whether caused by infection, dermatitis, or mechanical trauma—result in agglutination of the apposed labia minora by fibrous tissue on healing. The process typically begins posteriorly and extends forward. In most cases the fused portion is less than 1 cm in length, but on occasion it can extend to cover the vaginal vestibule and rarely the urethra (Fig. 18-12, A and B). Even when fusion is extensive, urine and vaginal secretions are able to exit through the opening anteriorly. However, some urine may become trapped behind the adhesions after toileting. This may cause further irritation, perpetuating the condition or fostering extension of the adhesions. Although most labial adhesions are asymptomatic, some patients have symptoms of lower urinary tract and vulval inflammation.

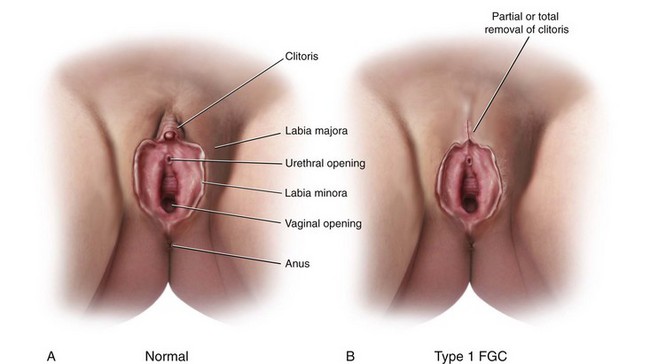

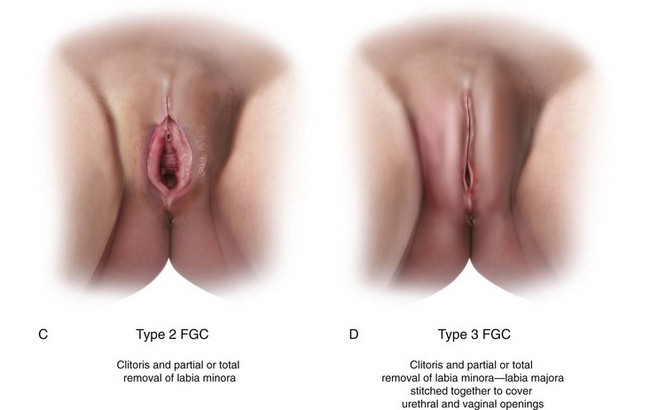

Female Genital Cutting

Female genital cutting (FGC) is another cause of genital tract obstruction seen with increasing frequency by pediatricians, especially those who care for large numbers of patients from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. This ritual cutting and alteration of female genitalia has no known medical benefits and carries potentially life-threatening short- and long-term health consequences. Figure 18-13, A-D illustrates the various types of FGC. Further information about this topic can be found at the World Health Organization website (see Websites, following the bibliography). The World Health Organization is working to eliminate this practice, considering it a human rights violation of girls and women. However, pediatricians who encounter girls who have undergone these procedures must be sensitive both to the complex religious and sociocultural norms that motivate families to practice FGC as well as to the consequences to the individual patient.

Imperforate Hymen

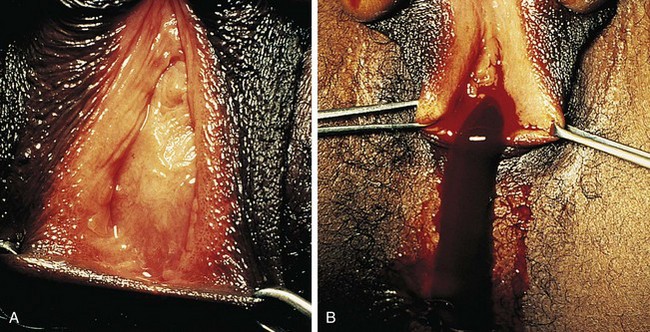

The congenital anomaly referred to as imperforate hymen consists of a thick imperforate membrane located just inside the hymenal ring. This is the most common truly obstructive abnormality. It is frequently missed on the newborn examination because of the redundancy of hymenal folds. However, it may become evident by 8 to 12 weeks of age on careful perineal inspection, appearing as a thin, transparent hymenal membrane that bulges when the infant cries or strains. On occasion, young infants have copious vaginal secretions secondary to stimulation by maternal hormones, and as a result of this anomaly they develop hydrocolpos. In such cases the infant may have midline swelling of the lower abdomen (especially noticeable when the bladder is full) that feels cystic on palpation. Perineal inspection reveals a whitish, bulging membrane at the introitus. The cystic mass may also be palpable on rectal examination. In the presence of a neonatal withdrawal bleed or trauma, a hematocolpos may develop. This presents as a red or purplish bulge (Fig. 18-14). Treatment consists of incision of the membrane to allow drainage, followed by excision of redundant tissue.

If her condition goes undetected, the patient with an imperforate hymen usually develops hematocolpos in late puberty. The major complaints are intermittent lower abdominal pain and low back pain, which rapidly progress in severity and duration. Over time difficulty in urination and defecation may develop, and a lower abdominal swelling may become noticeable. The patient has well-developed secondary sex characteristics but has had no menstrual periods. Perineal inspection reveals a thick, tense, bulging membrane, often bluish in color, at the introitus (Fig. 18-15, A). A low cystic swelling is palpable anteriorly on rectal examination. Operative incision allows drainage of the accumulated blood and vaginal secretions (Fig. 18-15, B) and is followed by excision of the membrane. Other partially obstructive hymenal abnormalities may allow menstrual blood to flow but later cause difficulty inserting tampons or initiating intercourse. Because hymens are not of müllerian origin, imperforate hymens are not associated with other genitourinary abnormalities.

Other forms of genital tract obstruction (Box 18-4) are rare. In most cases early routine genital inspection reveals the absence of a vaginal orifice, enabling early delineation of the anomaly and thus facilitating treatment. Proximal obstructing anomalies may not be apparent on physical examination. If missed in infancy or childhood, partial or complete obstruction can present with a wide range of signs and symptoms, such as those listed in Box 18-5. As noted earlier, ultrasonography is a valuable screening tool in evaluating girls suspected of having genital tract obstruction, bearing in mind its limitations in visualization of internal structures after the neonatal period and before puberty, when they are very small given minimal amounts of estrogen and gonadotropins. When structures are not seen or when further anatomic detail is required, consultation with a radiologist regarding an MRI is recommended.

Box 18-4 Causes of Genital Tract Obstruction

Labial fusion (underlying endocrine pathology)

Labial adhesions (partial obstruction)

Female genital cutting sequelae

Vaginal atresia (failure to canalize the vaginal plate)

Transverse vaginal septum at the junction of the upper one third and lower two thirds of the vagina

Androgen insensitivity (testicular feminization syndrome)

Tumors of the upper and lower genital tracts; other pelvic masses

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree