Newborn and Prepubertal Child

When examining a young child, it is important to put the child and parents at ease and gain their trust. The physician should explain to the child and her parent(s) exactly what will be done during the exam and why it is necessary. Focus should be placed on reassuring the parent(s) and explaining that the examination of a child is different from an examination of an adult. The child should be made to feel at ease and allowed to maintain some control of her environment; the goal is to examine the child without causing any traumatization to her. It may be helpful to allow the child to hold a handheld mirror so she may see her genitals at the same time they are being examined.

Children and younger adolescents are concrete thinkers—as such the most meaningful information may be imparted concurrent with the examination. It is important to point out to children after the exam that it was done because the parent or guardian agreed to it. This provides an opportunity to remind children that no one else should touch her genitals and if it happens, she should tell the parent(s) or guardian(s).

The genital examination should be incorporated into a complete physical examination. Begin the examination by visual inspection of the skin for rashes and lesions, and then listen to the heart and lungs. Visualization or palpation of the breast tissue allows determination of Tanner staging. The abdomen should be palpated for masses. The pelvic exam may be deferred until a subsequent visit in order to allow the girl time to develop a relationship with her new physician or provider unless there is a specific problem or urgent situation.

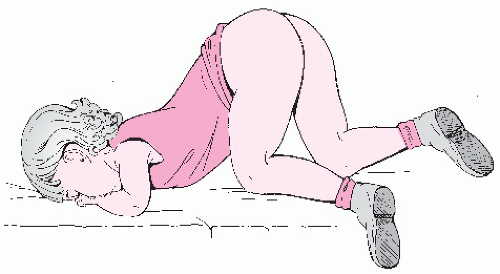

The undergarments may be removed immediately before the examination and the child should be offered and shown how to use a drape. Although the ideal position for good visualization of a young girls genitalia is supine, with her buttocks at the end of a gynecologic examination table, this is not typically feasible in younger children. Alternatively, the parent of a child can be positioned on the examination table, supported by elevating the head of the table, with the child positioned frog-leg style on the parent’s lap (

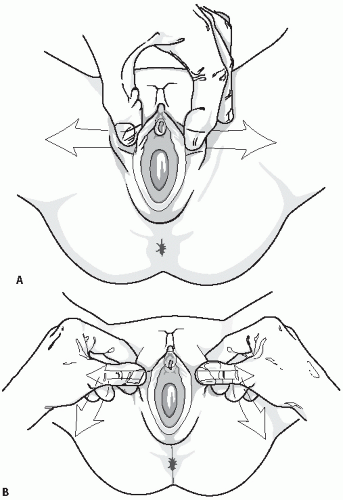

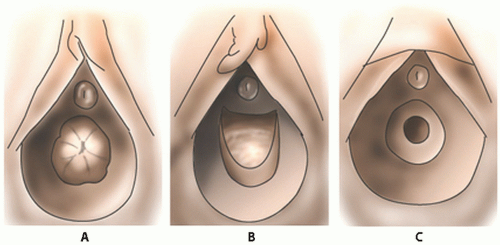

Fig. 23.1). Many children feel comforted in the arms and lap of their parent and it is an easy alternative method to allow inspection of the perineum. In the frog-leg position, the labia may be gently separated or gentle lateral traction on the labia majora may be used and this allows for better visualization of the hymen and vaginal orifice (

Fig. 23.2A,B). The child may also be allowed to use her own hands to spread the labia laterally to allow visualization of the vaginal introits. After examination in the frog-leg style, the child should be asked to get into the knee-to-chest position on the examination table (

Fig. 23.3). The kneeto-chest position offers an improved view of the vagina and more thorough inspection of both the posterior and anterior hymenal area.

Older patients may be able to be placed in the supine position but this position does not allow direct eye contact between the patient and her examiner. For this reason, we suggest that older children and teens sit up with their back supported at a 45-degree angle and their feet in stirrups. With the perineum exposed, a teaching examination can proceed (see next section).

Examination of a prepubertal child should not be done without some means of magnifying the area. A handheld magnifying glass with or without light, colposcope, or even an otoscope with the truncated ear canal piece removed may be used. The exam should be described in detail in the chart with a comment regarding the size, shape, or any abnormalities of the labia majora and minora (in children it may be hard to distinguish between these), clitoris, clitoral hood, urethra, vaginal orifice and vestibule, hymen, perineal body, and anus inclusive.

Because of their hypoestrogenic state, the genital tissues of young girls are very sensitive to touch and may be easily lacerated by instruments and even cotton tip swabs. A vaginal speculum should not be used in the pediatric patient. If a vaginal infection needs to be ruled out, a culture should be obtained by placing a very small moistened cotton swab, for example, a Calgi swab or a

small Dacron swab (male urethral size), just through the hymen with every effort made not to touch the sensitive hymen. If this is not possible, the culture swab may be placed between the labia, although this may not yield adequate sampling for diagnosis.

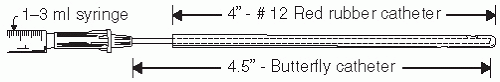

If the vagina needs to be flushed, for example, looking for a foreign body, a soft rubber catheter works quite well. However, it is not ideal for obtaining secretions for culture because the tip will be sucked against the vaginal wall when the vaginal fluid (either naturally occurring or the combination of saline that has been introduced into the vagina via the catheter and then is aspirated) is aspirated. One option is to use a “catheter within a catheter” (

Fig. 23.4). A 4.5 in butterfly intravenous (IV) tube may be passed into the distal 4.5 inches of a soft, no. 12, red rubber catheter that is attached to a 1 to 3 mL syringe to allow for 0.5 to 1 mL of fluid to be flushed into the vagina and aspirated back into the syringe. This can be done several times to get a good mixture of upper vaginal secretions and the aspirant may be sent for wet mount, Gram stains, cultures, and forensic material. The lab should be told that the specimen was obtained from a prepubertal child. Most children are amenable to this procedure if they are shown there is no needle attached to the apparatus and it may be helpful to place a few drops of the liquid on their hand or fingers to reassure them.

The vaginal pH in prepubertal girls is 6.5 to 7.5 and is therefore not useful for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis or trichomonal infections in these girls.

If a more thorough examination of the vagina of a prepubertal child is necessary (e.g., unexplained vaginal bleeding, suspicion of a foreign object or trauma), vaginoscopy is recommended. The vaginal endoscopic examination via cystoscopy or hysteroscopy employs normal saline (in a bag draining to gravity) to distend the vagina while the labia are held gently together, allowing the vagina to distend and facilitate evaluation. Application of 2% lidocaine jelly to the external vaginal area and to the tip of a vaginoscope enables more comfortable placement into the vagina. This may be accomplished in a cooperative patient in an outpatient setting or may require general anesthesia in a young or frightened child.

6 A young child’s vagina is about 5 cm in length and the mucosa is red, thin, and slightly folded. The cervix is small, with a central opening, and is often flush with the vagina. Vaginoscopy may cause petechiae of the vaginal mucosa given how thin and sensitive it is.

Clitoral size may be determined by the clitoral index, which is calculated as the product of the length and width of the clitoris and expressed in square millimeters. Charts indicating the normal clitoral index by age are available (

Table 23.1). If the clitoris is enlarged, causes of androgen stimulation should be sought (

Table 23.2).

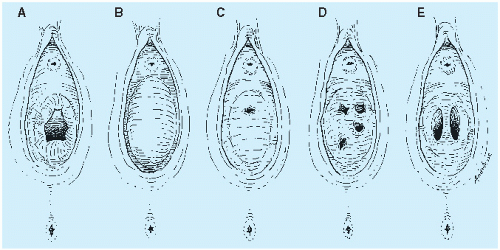

It is important to realize that hymens change with age and weight. Infant girls have estrogenized hymens and

may have a prominent ridge at 6 o’clock. The hymen of prepubertal girls is unestrogenized, thin, and may have a multitude of appearances (

Figs. 23.5 and

23.6).

Infantile perianal pyramidal protrusion (IPPP) is a perianal lesion that has been previously described as a skin tag or fold and is seen almost only in girls

7 (

Fig. 23.7). It may be perineal in location rather than perianal but is typically midline and usually anterior to the anus, although they may rarely be posteriorly located to the anus.

8 It is not tender and treatment is not indicated. Clinically, they may undergo cycles of swelling followed by spontaneous resolution.

Pubertal and Postpubertal Adolescent

In the initial examination of the young adolescent, often only the external genital area needs to be viewed, in which case placement of a speculum or an internal examination is not necessary. This often reassures both the patient and her parent who may have negative attitudes about the use of a vaginal speculum and allows the clinician to present the external genital examination in the context of routine adolescent health care.

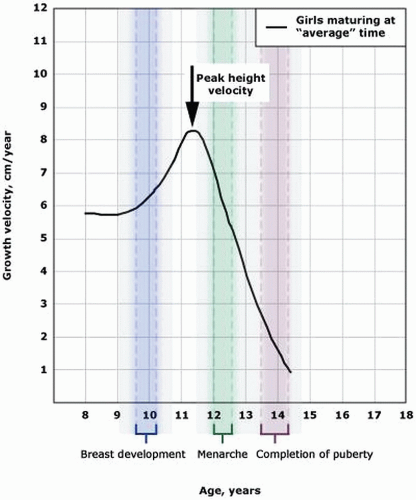

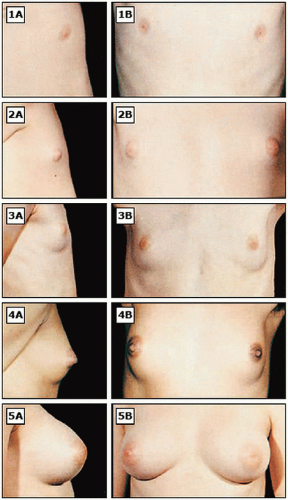

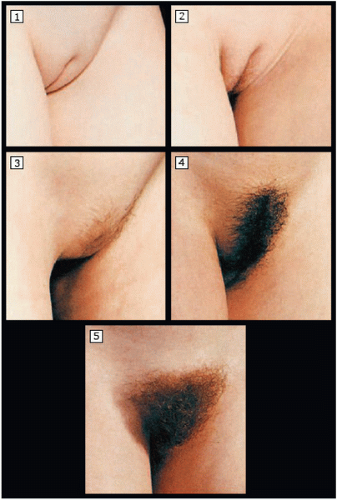

It is important for clinicians to be familiar with normal variations of pubertal maturation, so that abnormalities of puberty can be recognized and treated in a timely manner. Puberty consists of a series of predictable sequence of events and the most common staging system is the “Tanner stages” of puberty (

Figs. 23.8,

2.9 to

23.10).

Normal puberty begins when gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released from the hypothalamus in a pulsatile manner, activating the release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

from the pituitary. LH induces production of androstenedione from the ovarian theca cells, and FSH induces synthesis of estradiol from the follicular cells. At puberty, changes related to estrogen include breast development, enlargement of the labia minora, and edematous and pink changes in the hymenal tissues. The increase in estradiol causes breast development (thelarche) and the growth spurt in girls.

9 The earliest secondary sexual characteristic in most girls is breast/areolar development, although some may exhibit pubic hair growth first. Menarche occurs, on average, 2.6 years after the onset of puberty.

Adrenarche (pubic hair development) is initiated by adrenal androgen production and usually begins approximately 6 months after thelarche, at an average age of 11 to 12 years. Pubic hair may be a normal first sign of development in some girls (as early as age 7 years), particularly in those of African American descent.

10 The Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society has recommended guidelines for the valuation of premature development, which state that pubic hair or breast development requires evaluation only when it occurs before age 7 years in non-African American girls and before age 6 years in African American girls.

11 These recommendations are controversial, however, as they lower the age threshold for evaluation for precocious puberty and this may lead to failure to identify some children with disease processes that may be amenable to intervention.

12Menarche typically occurs within 2 to 3 years after thelarche, at a median age of 12.4 years.

13 Onset of puberty is affected by race, family history, birth weight, nutrition, international adoption, and exposure to estrogenic chemicals. For reasons that remain unclear, the age of menarche has declined to a greater extent in Black girls compared to White girls over the last several decades.

14 When menarche occurs before the age of 12 years, it is associated with increases in weight and body mass index (BMI).

15About 17 to 18% of final adult height accrues during puberty, with the limbs exhibiting an accelerated growth prior to the truncal portions of the body.

16 The peak growth velocity usually begins about 2 years earlier in girls than in boys and occurs about 6 months or so prior to menarche.

17 About half of a woman’s total body calcium is laid down during puberty.

18,19 Changes in bone growth and mineralization patterns may put some adolescents at increased risk for fracture. If a patient has scoliosis, progression of the degree of scoliosis may occur during puberty as a result of growth in the axial skeleton.

The increase in BMI prior to 16 years of age that is seen with puberty is usually due in increases in fat-free mass; after age 16 years, increasing BMI is primarily due to increases in fat mass.

20The vagina and hymen become more distensible during puberty. Despite historical documentation and cultural beliefs, recent research has shown that even an experienced clinician cannot tell if a postpubertal woman has had genital penetration based on the physical examination.

21Any signs of inflammation, lesions or pigment changes seen on the exam should be noted. Folliculitis, presenting as tender papules and pustules, has become increasingly common in adolescents who shave their pubic hair.

5 As noted earlier, an enlarged clitoris (>10 mm

3) may indicate elevated androgens. Asymmetry of the labia, where the right and left labia are different in size and appearance, is a normal variant. Some young women are uncomfortable with asymmetric labia or enlarged labia minora and complain about self-consciousness and discomfort while wearing clothing, exercising, or having intercourse. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) does not support performing cosmetic surgical procedures of labia minora unless there is significant impairment in function.

22A physiologic clear vaginal secretion may be worrisome for a peripubertal girl or young teen. Teens should be reassured that this nonirritating, nonodorous discharge is normal physiologic leukorrhea and reflects the effect of estrogen on the cells lining the vagina. Peri- and postpubertal children will have normal vaginal secretions with an acidic pH due to the effect of the protective population of lactobacilli that thrive in the glucose-rich environment of an estrogenized vagina.

The examination of adolescents is a golden opportunity to teach genital anatomy and hygiene. Teens appreciate a nonjudgmental and unhurried provider who is willing to answer their questions. As in the pediatric

patient, examination of the adolescent breast should include Tanner staging. Self-examination of the breast for those aged 13 to 18 years is not recommended because the risk for breast pathology is low.

23 The pelvic exam should be explained prior to beginning the exam. In general, all adolescents benefit from an educational external genital examination, with the provider indicating the anatomic findings while the patient simultaneously watches using a handheld mirror. Instruction in genital hygiene, including wiping from front to back; using wet wipes after bowel movements; cleansing the folds of the labia majora and minora during baths or showers; and avoidance of douching, chemical irritants, and perfumed or deodorant soaps is crucial advice for young women.

If testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (either due to abuse or sexual activity) is indicated, a speculum examination is not required to obtain an endocervical specimen given the current availability and efficacy of urine-based gonorrhea and chlamydia nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT).

24 The recently revised 2009 ACOG guidelines for cervical cancer screening state that the first Pap test should be performed at age 21 years regardless of the age of first intercourse.

25 The exception to this general rule is if the patient has HIV and is sexually active, initial screening should include a Pap test and pelvic exam; the Pap test should be obtained twice during the first year after diagnosis of HIV infection and, if the results are normal, annually thereafter.

26If necessary to evaluate abnormal bleeding or other pathology in a young teen, a narrow Pederson speculum may be used to visualize the cervix and vaginal mucosa. To assess a possible pelvic mass, a young adolescent, even one who has never been sexually active, may undergo a single digit bimanual exam or rectal exam.

Alternatively, a transabdominal ultrasound may be used to document internal genital structures as long as the bladder is well-filled.

Anemia and iron deficiency are common among adolescent girls, reflecting the changes in hemoglobin and serum ferritin concentrations, which are influenced by both sex and pubertal stage. Both hemoglobin and serum ferritin concentrations increase in adolescent boys but not in girls; coupled with menstrual bleeding and insufficient anemia, this predisposes pubertal girls to anemia.

27