Endometrial hyperplasia

Non-atypical hyperplasia

Simple

Complex

Atypical hyperplasia

Simple

Complex

Papillary hyperplasia

Simple

Complex

Endometrial polyp

Tamoxifen-related lesions

Endometrial carcinoma

(i) Endometrioid adenocarcinoma

Variant with squamous differentiation

Villoglandular variant

Secretory variant

Ciliated variant

(ii) Mucinous adenocarcinoma

(iii) Serous adenocarcinoma

(iv) Clear cell adenocarcinoma

(v) Mixed cell adenocarcinoma

(vi) Squamous cell carcinoma

(vii) Malignant mixed müllerian (mesodermal) tumor (MMMT) (carcinosarcoma)

(viii) Transitional cell carcinoma

(ix) Small cell carcinoma

(x) Undifferentiated carcinoma

(xi) Others

Simple Hyperplasia

Histopathological appearance of simple hyperplasia includes uniformly rounded glands with marked variation in shape, including several cystically dilated forms. The lining epithelium of the glands reveals pseudostratification or multilayering, but lacks nuclear atypia. This may be associated with tubal metaplasia. The stroma is compact (Fig. 10.1). The differential diagnoses include atrophy, wherein glands are lined by flattened epithelium and benign endometrial polyp, in which the glands are covered by a similar benign-appearing hyperplastic epithelium on three surfaces with hyperplastic glands within the stroma that also contains blood vessels (Fig. 10.2). Simple cystic hyperplasia also should be differentiated from proliferative and disordered endometrium, especially the latter wherein endometrial glands are hyperplastic, but without an increase in volume [5]. Chronic endometritis can lead to an overdiagnosis of atypical hyperplasia, especially when inflammatory cells lead to reactive nuclear atypia noted within the glands. The presence of neutrophils on surface and plasma cells within stroma is indicative of chronic endometritis.

Fig. 10.1

Simple cystic hyperplasia comprising benign-appearing cystically dilated endometrial glands, exhibiting tubal metaplasia (cells with ciliated surface projecting into the lumens) in a compact cellular stroma. Hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) ×400

Fig. 10.2

(a) Benign endometrial polyp revealing endometrial epithelial lining on three surfaces with variably sized endometrial glands and several blood vessels within stroma. H&E ×40. (b) Benign endometrial glands within stroma revealing cystic dilatation with interspersed blood vessels. H&E ×200

One needs to be careful in such cases, especially while dealing with a biopsy. Clinically, patient history related to intake of hormonal medications and an appraisal of thickness of the endometrium, on imaging, are useful in reinforcing a correct diagnosis in some cases with equivocal histopathological features.

Complex Hyperplasia (Typical and Atypical)

This reveals increase in endometrial glands leading to their fusion and causing a common arch bars between the glands. While lack of atypia is noted in simple and complex hyperplasias without atypia, atypical hyperplasias reveal nuclear and cytoplasmic abnormality in the form of lack of polarity, irregular multilayering, and anisocytosis, accompanied by nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, chromatin clumping, and prominent nucleoli [5, 6]. Invariably, atypical hyperplasias are complex, wherein cribriform appearance of glands is noticeable, and in certain such cases, differentiation from grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma becomes challenging (Fig. 10.3).

Fig. 10.3

Complex atypical hyperplasia (CAH). (a) Atypical endometrial glands exhibiting complex architecture with endometrial stroma between the glands, reported as CAH. H&E ×200. (b) The same case at higher magnification revealing complex architecture of glands associated with nuclear atypia. H&E ×400. Diagnosis on hysterectomy was well-differentiated FIGO grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma. (c) Residual CAH reported on hysterectomy specimen in a case wherein curettage specimen revealed well-differentiated FIGO grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Complex architecture of glands with nuclear atypia and conspicuous interglandular stroma. H&E ×200. (d) The same case revealing focal eosinophilic metaplasia. H&E ×400

Papillary Hyperplasia

These are rather uncommon lesions. Papillary proliferations of the endometrium were initially reported by Lehman and Hart [7], who described nine cases mostly in postmenopausal women, who presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding. Invariably these lesions were found to be associated with intake of hormonal medications. Their cases included five of simple papillary proliferations and four of complex papillary proliferations, all associated with metaplastic changes. In another study [8], 59 cases of papillary proliferations of the endometrium without atypia in patients with similar age and symptomatology were analyzed. They classified their study cases as group I lesions (61 %) with localized simple papillae that were further defined as those with short, predominantly non-branching stalks and group II lesions (39 %) comprising complex papillae and/or those with diffuse and crowded intracystic papillae. Complex papillae were defined as those with both short or long stalks and, invariably, secondary and complex branches. These authors [7, 8] concluded that cases with group 2 features were significantly associated with concurrent or subsequent premalignant lesions (non-atypical and atypical hyperplasia) or carcinoma. Furthermore, they suggested that these lesions are analogous to atypical complex hyperplasia, and they termed these as “complex papillary hyperplasia (CPH)” (Fig. 10.4). Recently, a similar case of complex papillary hyperplasia was reported that was initially misdiagnosed as uterine papillary serous carcinoma [9].

Fig. 10.4

Complex papillary hyperplasia endometrium displaying primary and tertiary ramifications leading to complex papillary formations, lined by “banal” epithelium lacking significant nuclear atypia. H&E ×200

Endometrial Adenocarcinoma

Histopathologically, these are classified as villoglandular, secretory, or ciliated cell carcinoma; endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation; and serous, clear cell, mucinous, “pure” squamous cell, mixed, neuroendocrine, or undifferentiated carcinoma. Noteworthy, malignant mixed müllerian tumor (MMMT)/carcinosarcoma is also classified under the rubric of endometrial adenocarcinomas [6].

Clinicopathologically, endometrial adenocarcinomas are broadly subclassified as type I and type II adenocarcinomas. Type 1 endometrial adenocarcinomas are generally of low-grade and include secretory, ciliated, and villoglandular variants of an endometrioid adenocarcinoma. These are associated with unopposed estrogen stimulation and arise on a background of hyperplasia.

On the other hand, type 2 endometrial adenocarcinomas are invariably of high-grade and comprise serous, “pure” squamous, neuroendocrine, undifferentiated, and clear cell types of endometrial adenocarcinomas, along with malignant mixed müllerian tumors (MMMTs)/carcinosarcomas. These, especially serous type, arise on a background of atrophic endometrium and are associated with intraepithelial carcinoma.

The dualistic classification also has a molecular basis along with prognostic and therapeutic relevance. Type I cancers are associated with phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mutation, microsatellite instability, and K-ras mutation, whereas type II adenocarcinomas are associated with p53 mutation. Type I adenocarcinomas are associated with a relatively good prognosis. In some of these cases, “nonsurgical” treatment is opted, such as progesterone therapy. Contrastingly, type II adenocarcinomas are associated with a relatively poor prognosis. In most of these tumors, adjuvant treatment, in the form of chemotherapy (CT) and/or radiotherapy (RT), is included [6, 10].

Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma

Gross appearance of an endometrioid carcinoma includes a variably glistening, shaggy, and/or hemorrhagic external surface. On cutting open, most of the cancers are focally or diffusely exophytic, even when deeply invasive. In cases of serous adenocarcinomas, the uterus is relatively small and atrophic and reveals papillary excrescences on the cut surface. MMMTs are invariably polypoid and extensively fill the endometrial cavity (Figs. 10.5 and 10.6 a, b).

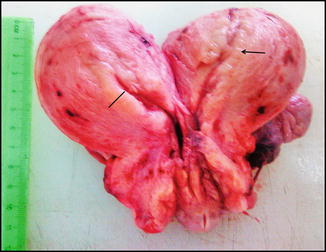

Fig. 10.5

Cut open hysterectomy specimen in a middle-aged lady displaying thickened endometrium (marked) with irregularity on other side (arrow). Microscopy showed a well differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma (FIGO grade I) arising on a background of complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia

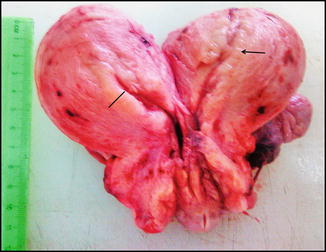

Fig. 10.6

(a) Cut open specimen of total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexae/salpingo-oophorectomy (fresh state), showing a proliferative endometrial carcinoma, filling the entire uterine cavity. (b). Gross appearance of an endometrioid carcinoma (fixed specimen). Anteriorly cut open total abdominal hysterectomy specimen with bilateral adnexae displaying polypoid tumor in the endometrial cavity. Histopathology revealed well differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma

Microscopic examination of endometrioid adenocarcinomas is based upon incorporation of architectural patterns and severity of nuclear atypia. Endometrioid adenocarcinomas are classified as grade 1 (not more than 5 % of tumor composed of solid pattern), grade II (6–50 % tumor reveals solid pattern), and grade III (more than 50 % of tumor displays solid pattern). Nuclear grading is based on mild (grade I), moderate (grade II), and marked (grade III) nuclear atypia. In the case of lower architectural grade and higher nuclear grade, the overall grade is escalated. For example, architecturally, grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma with moderate nuclear atypia is assigned FIGO grade II [6]. Finally, endometrioid adenocarcinomas are graded as well-differentiated (FIGO I), moderately differentiated (FIGO II), and poorly differentiated (FIGO III) carcinomas. On immunohistochemistry, most well to moderate endometrioid adenocarcinomas display positive estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) staining (Figs. 10.7 and 10.8). At times, endometrioid adenocarcinomas display squamous differentiation that is a metaplastic change (Fig. 10.9).

Fig. 10.7

(a) Microscopic findings of endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Well-differentiated/FIGO grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma displaying “back to back” arrangement of endometrial glands with minimal to absent stroma between the tumor glands. Tumor cells exhibit mild nuclear atypia. H&E ×200. (b) Same case showing intraluminal necrotic debris and inflammatory cell within one of the atypical glands. H&E ×200. (c) Foamy histiocytes within interglandular area, suggestive of well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma. H&E ×400. (d) Diffuse estrogen receptor (ER) positivity (brown staining in the nuclei) within tumor glands in a case of well-differentiated/FIGO grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) immunostaining ×400

Fig. 10.8

(a) Case of a moderately differentiated/FIGO grade II endometrial adenocarcinoma. Tumor seems to retain glandular pattern, but nuclear atypia is moderate. H&E ×200. (b) In the same tumor, p53 immunostaining noted in several tumor nuclei. (c) Case of poorly differentiated FIGO grade III endometrioid adenocarcinoma displaying solid pattern of cells exhibiting marked nuclear atypia. Glandular differentiation is lacking. H&E ×400. (d) Same tumor displaying loss of ER expression. Interspersed are few benign endometrial glands (arrow) and interspersed stromal cells displaying positive immunostaining, acting as internal positive control. DAB ×200

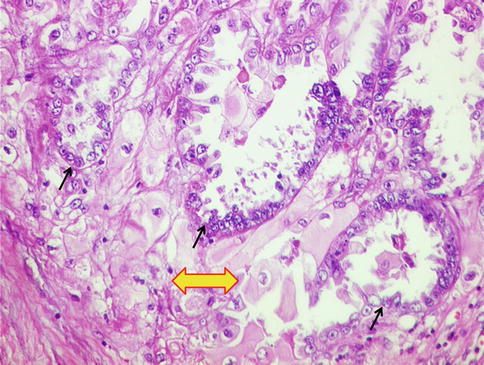

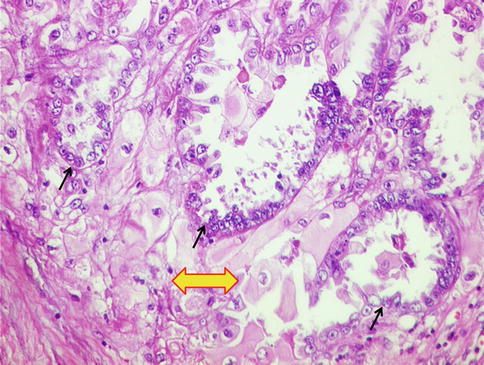

Fig. 10.9

Squamous differentiation in the form of pink cells with intercellular bridges (thick yellow arrow) in a well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma (arrows). H&E ×200

Serous Adenocarcinoma

This occurs over a wide clinical age group. Unlike endometrioid adenocarcinomas, in such cases, history of estrogen replacement therapy is less likely than abnormal cervical cytology. As aforementioned, the uterus in such cases is small and atrophic. Microscopically, this tumor is characterized by an array of patterns, although papillary pattern is more common. Besides, glandular and solid patterns are also noted. Characteristically, papillary structures lined by markedly atypical cells, exhibiting “hobnail” pattern, are noted with readily identifiable mitotic figures. These are associated with intraepithelial carcinoma along with atrophied endometrium. On immunohistochemistry (IHC), these tumors exhibit diffuse p53 and p16 immunostaining (Fig. 10.10).

Fig. 10.10

(a) High-grade papillary serous adenocarcinoma. H&E ×200. (b) Same tumor displaying diffuse p53 immunostaining (brown staining in the nuclei). DAB ×400

Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma

While these tumors have nonspecific gross findings, microscopically they exhibit solid, papillary, tubular, and cystic patterns. Cells exhibit marked pleomorphism, conspicuous hobnail arrangement, variably eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm, and prominent eosinophilic nucleoli in several cells. Stroma is hyalinized leading to formations of eosinophilic bodies. Deep purple psammoma bodies may be identified. The differential diagnoses include Arias-Stella reaction, serous adenocarcinoma, secretory type of endometrioid carcinoma, and yolk sac tumor. On IHC, this tumor expresses CK7 and vimentin and lacks ER, PR, p53, and p16 expression (Fig. 10.11).