Chapter 632 Otitis Media

Accurate diagnosis of OM in infants and young children may be difficult (Table 632-1). Symptoms may not be apparent, especially in early infancy and in chronic stages of the disease. The eardrum may be obscured by cerumen, removal of which may be arduous and time-consuming. Abnormalities of the eardrum may be subtle and difficult to appreciate. In the face of these difficulties, both underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis occur. Once a diagnosis of OM has been established, its significance to the child’s health and well-being and its optimal method of management remain open to question and the subjects of continuing controversy. There is lack of consensus among authorities concerning benefit-risk ratios of available medical and surgical treatments; while OM can be responsible for serious infectious complications, middle- and inner-ear damage, hearing impairment, and indirect impairments of speech, language, cognitive, and psychosocial development, most cases of OM are not severe and are self-limiting.

Table 632-1 DEFINITION OF ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA

AOM, acute otitis media; MEE, middle-ear effusion; TM, tympanic membrane.

From Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media: Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media, Pediatrics 113:1451–1465, 2004.

Epidemiology

Congenital Anomalies

OM is universal among infants with unrepaired palatal clefts, and is also highly prevalent among children with submucous cleft palate, other craniofacial anomalies, and Down syndrome (Chapter 76). The common feature in these congenital anomalies is a deficiency in the functioning of the eustachian tubes, which predisposes these children to middle ear disease.

Vaccination Status

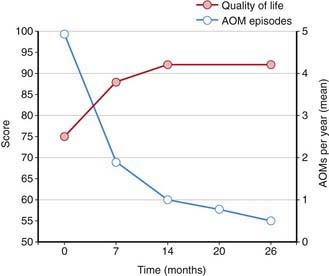

Streptococcus pneumoniae (Chapter 175) has historically been the most common pathogen identified in patients with acute OM. Vaccination of infants with a conjugated pneumococcal vaccine has a modest effect, lowering visits to physicians and antibiotic prescriptions for OM by only 6-8%. Vaccination does appear to have a somewhat more protective effect in limiting frequent OM episodes and the need for surgical intervention with tympanostomy tubes. Pneumococcal vaccination has decreased the overall rate of episodes of OM associated with pneumococcus and increased quality of life (Fig. 632-1). Annual influenza virus vaccination also results in a decrease in OM incidence.

Pathogenesis

Host Factors

The effectiveness of a child’s immune system in response to the bacterial and viral insults of the upper airway and middle ear during early childhood probably is the most important factor in determining which children are otitis prone. The maturation of this immune system during early childhood is most likely the primary event leading to the decrease in incidence of OM as children move through childhood. IgA deficiency is found in some children with recurrent AOM but the significance is questionable, inasmuch as IgA deficiency is also found not infrequently in children without recurrent AOM. Selective IgG subclass deficiencies (despite normal total serum IgG) may be found in children with recurrent AOM in association with recurrent sinopulmonary infection, and these deficiencies probably underlie the susceptibility to infection. Children with recurrent OM that is not associated with recurrent infection at other sites rarely have a readily identifiable immunologic deficiency. Nonetheless, evidence that subtle immune deficits play a role in the pathogenesis of recurrent AOM is provided by studies involving antibody responses to various types of infection and immunization; by the observation that breast milk feeding, as opposed to formula feeding, confers limited protection against the occurrence of OM in infants with cleft palate; and by studies in which young children with recurrent AOM achieved a measure of protection from intramuscularly administered bacterial polysaccharide immune globulin or intravenously administered polyclonal immunoglobulin. This evidence, along with the documented decrease incidence of upper respiratory tract infections and OM as children’s immune systems develop and mature is indicative of the importance of a child’s innate immune system in the pathogenesis of OM (Chapter 118).

Viral Pathogens

Although OM may develop and certainly may persist in the absence of apparent respiratory tract infection, many, if not most, episodes are initiated by viral or bacterial upper respiratory tract infection. In a study of children in group daycare, AOM was observed in approximately 30-40% of children with respiratory illness caused by RSV (Chapter 252), influenza viruses (Chapter 250), or adenoviruses (Chapter 254), and in approximately 10-15% of children with respiratory illness caused by parainfluenza viruses, rhinoviruses, or enteroviruses. Viral infection of the upper respiratory tract results in release of cytokines and inflammatory mediators, some of which may cause eustachian tube dysfunction. Respiratory viruses also may enhance nasopharyngeal bacterial colonization and adherence and impair host immune defenses against bacterial infection.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms of AOM are variable, especially in infants and young children. In young children, evidence of ear pain may be manifested by irritability or a change in sleeping or eating habits and occasionally, holding or tugging at the ear (see Table 632-1). Pulling at the ear has a low sensitivity and specificity. Fever may also be present. Rupture of the tympanic membrane with purulent otorrhea is uncommon. Systemic symptoms and symptoms associated with upper respiratory tract infections also occur; occasionally there may be no symptoms, the disease having been discovered at a routine health examination. OME often is not accompanied by overt complaints of the child but can be accompanied by hearing loss. This hearing loss may manifest as changes in speech patterns but often goes undetected if unilateral or mild in nature, especially in younger children. Balance difficulties or disequilibrium can also be associated with OME and older children may complain of mild discomfort or a sense of fullness in the ear (Chapter 628).

Examination of the Eardrum

Diagnosis

A certain diagnosis of OM should contain all of the following elements: (1) recent and usually acute onset of illness, (2) presence of MEE, and (3) signs and symptoms of middle-ear inflammation including erythema of the tympanic membrane or otalgia (see Table 632-1). A simplified differentiating schema establishes a diagnosis of AOM when, in addition to having MEE, a child gives evidence of recent, clinically important ear pain or the tympanic membrane shows marked redness or distinct fullness or bulging.

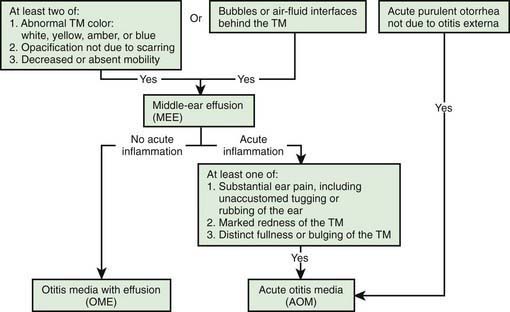

Distinguishing between AOM and OME on clinical grounds is straightforward in most cases, although each condition may evolve into the other without any clearly differentiating physical findings; any schema for distinguishing between them is to some extent arbitrary. In an era of increasing bacterial resistance, distinguishing between AOM and OME is important in determining treatment, because OME in the absence of acute infection does not require antimicrobial therapy. Purulent otorrhea of recent onset is indicative of AOM; thus, difficulty in distinguishing clinically between AOM and OME is limited to circumstances in which purulent otorrhea is not present. Both AOM without otorrhea and OME are accompanied by physical signs of MEE, namely, the presence of at least 2 of 3 tympanic membrane abnormalities: white, yellow, amber, or (rarely) blue discoloration; opacification other than that due to scarring; and decreased or absent mobility. Alternatively in OME, either air-fluid levels or air bubbles outlined by small amounts of fluid may be visible behind the tympanic membrane, a condition often indicative of impending resolution (Fig. 632-2).

Figure 632-2 Algorithm for distinguishing between acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion. TM, tympanic membrane.

To support a diagnosis of AOM instead of OME in a child with MEE, distinct fullness or bulging of the tympanic membrane may be present, with or without accompanying erythema; or, at minimum, MEE should be accompanied by ear pain that appears clinically important. Unless intense, erythema alone is insufficient because erythema, without other abnormalities, may result from crying or vascular flushing. In AOM the malleus may be obscured, and the tympanic membrane may resemble a bagel without a hole but with a central depression (Fig. 632-3). Rarely the tympanic membrane may be obscured by surface bullae, or may have a cobblestone appearance. Bullous myringitis is a physical manifestation of AOM and not an etiologically discrete entity. Within days after onset, fullness of the membrane may diminish, even though infection may still be present.

In OME, bulging of the tympanic membrane is absent or slight or the membrane may be retracted (Fig. 632-4); erythema also is absent or slight, but may increase with crying or with superficial trauma to the external auditory canal incurred in clearing the canal of cerumen. In children with MEE but without tympanic membrane fullness or bulging, the presence of unequivocal ear pain is usually indicative of AOM.

Tympanometry

Tympanograms may be grouped into 1 of 3 categories (Fig. 632-5). Tracings characterized by a relatively steep gradient, sharp-angled peak, and middle-ear air pressure (location of the peak in terms of air pressure) that approximates atmospheric pressure (Fig. 632-5A) (type A curve) are assumed to indicate normal middle-ear status. Tracings characterized by a shallow peak or no peak and by negative or indeterminate middle-ear air pressure, and often termed “flat” or type B (Fig. 632-5B), usually are assumed to indicate the presence of a middle-ear abnormality that is causing decreased TM compliance. The most common such abnormality, by far, in infants and children is MEE. Tracings characterized by intermediate findings—somewhat shallow peak, often in association with a gradual gradient (obtuse-angled peak) or negative middle-ear air pressure, or combinations of these features (Fig. 632-5C)—may or may not be associated with MEE, and must be considered nondiagnostic or equivocal. In general, the shallower the peak, the more gradual the gradient, and the more negative the middle-ear air pressure, the greater the likelihood of MEE.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree