The kidneys of non-pregnant women start to excrete glucose at a threshold level of 11 mmol/L. In pregnancy this varies more but often decreases, so glycosuria may occur at physiological blood glucose concentrations. Raised fetal blood glucose levels induce fetal hyperinsulinaemia, causing fetal fat deposition and excessive growth (macrosomia).

Definition and Epidemiology

Pre-existing diabetes (whether type I or II) affects 1% of pregnant women. In those on insulin, increasing amounts will be required in these pregnancies to maintain normoglycaemia.

Gestational diabetes is ‘carbohydrate intolerance which is diagnosed in pregnancy and may or may not resolve after pregnancy’ (NICE 2008). By traditional definitions it did resolve, or at least glucose levels were not at a level normally treated outside pregnancy. It is becoming more common, largely because of increasing levels of obesity and varying definitions: NICE uses a fasting glucose level >7.0 mmol/L or >7.8 mmol 2 h after a 75-g glucose load (glucose tolerance test: GTT); a recent international consensus (IADPSG) (Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 676) uses more broader criteria of one of the following: fasting glucose >5.1 mmol/L or >10.0 mmol/L at 1 h, or >8.5 mmol/L at 2 h after a 75-g glucose load. The NICE definition encompasses 3.5% of pregnant UK women; that of the international consensus over 16%.

There is increasing evidence in favour of treatment of women with glucose intolerance that is milder than current NICE definitions. It is therefore likely that the broader international consensus will ultimately be adopted.

Diabetes in Pregnancy

| Pre-existing diabetes (<1%): | Insulin requirements increase in pregnancy |

| Gestational diabetes (3.5–16%): | Glucose levels rise temporarily to diabetic level (definitions vary) |

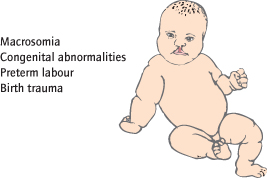

Fetal Complications (Fig. 21.2 )

Complications are related to glucose levels, so gestational diabetics are less affected. Type I and II diabetics are similarly affected. Congenital abnormalities (particularly neural tube and cardiac defects) are 3–4 times more common in established diabetics, and are related to periconceptual glucose control. Preterm labour, natural or induced, occurs in 10% of established diabetics, and fetal lung maturity at any given gestation is less than with non-diabetic pregnancies. Birthweight is increased as fetal pancreatic islet cell hyperplasia leads to hyperinsulinaemia and fat deposition. This leads to increased urine output and polyhydramnios (increased liquor) [→ p.164] is common. As the fetus tends to be larger, dystocia and birth trauma (particularly shoulder dystocia) are more common. Fetal compromise, fetal distress in labour and sudden fetal death are more common, and related particularly to poor third trimester glucose control.

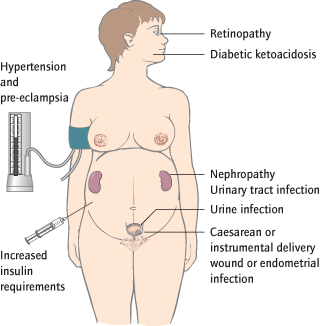

Maternal Complications (Fig. 21.3 )

Complications are related to glucose levels, so gestational diabetics are less affected. Insulin requirements normally increase considerably by the end of pregnancy. Ketoacidosis is rare, but hypoglycaemia may result from attempts to achieve optimum glucose control. Urinary tract infection and wound or endometrial infection after delivery are more common. Pre-existing hypertension is detected in up to 25% of overt diabetics and pre-eclampsia is more common. Pre-existing ischaemic heart disease often worsens. Caesarean or instrumental delivery is more likely because of fetal compromise and increased fetal size. Diabetic nephropathy (5–10%) is associated with poorer fetal outcomes but does not usually deteriorate. Diabetic retinopathy often deteriorates and may need to be treated in pregnancy.

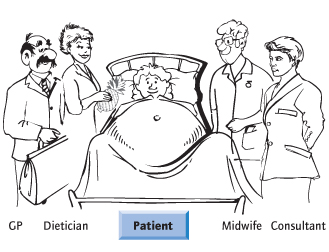

Management of Pre-Existing Diabetes in Pregnancy

Precise glucose control and fetal monitoring for evidence of compromise are the cornerstones of management. Antenatal care is consultant-based, with delivery in a unit with neonatal intensive care facilities. A multidisciplinary approach involving an obstetrician, midwife, GP, dietician and a physician is necessary (Fig. 21.4). The key member, however, is the woman, who has day-to-day control of her diabetes and needs to be educated about optimizing control. If she is not motivated, normoglycaemia will not be achieved.

Preconceptual Care

Insulin-dependent diabetic women wishing to undergo pregnancy should have their renal function, blood pressure and retinae assessed. Glucose control is optimized, and folic acid 5 mg/day is prescribed. Optimal control reduces the risk of congenital abnormalities and preterm labour. Labetalol or methyldopa are used if antihypertensives are required. Unfortunately, prepregnancy assessment seldom happens.

Monitoring and Treating the Diabetes

High concentrations of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) reflect poor prior control: the aim is for a level less than 7%. Visits occur fortnightly up to 34 weeks and weekly thereafter. Glucose levels are checked by the patient several times daily before and after food, and before bed, with a home ‘glucometer’. The ideal is levels consistently between below 6 mmol/L. In type II diabetics, and hypoglycaemic agents may need to be supplemented with insulin. Careful diet and a combination of one night-time-long/intermediate-acting, usually with three preprandial short-acting insulin injections are used. Doses will usually need to be progressively increased as the pregnancy advances, and glucagon should be prescribed in case of hypoglyaemia.

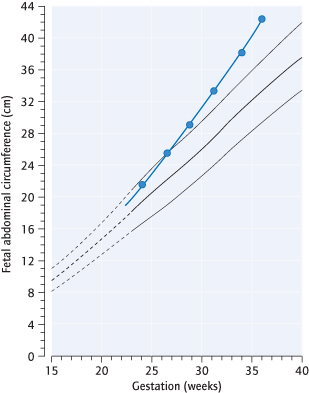

Monitoring the Fetus

In addition to the usual pregnancy scans [→ p.149], fetal echocardiography is indicated. Ultrasound is used to monitor fetal growth and liquor volume. Even where glucose control has been good, macrosomia and polyhydramnios can occur (Fig. 21.5). Umbilical artery Doppler is not useful unless pre-eclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) develop.

Monitoring or Treating the Complications of Diabetes

The renal function should be checked and the retinae screened for retinopathy. Aspirin, 75 mg daily from 12 weeks is advised to reduce the risk of pre-eclampsia. Diabetic acidosis, usually ketotic, is a medical emergency, and should be treated appropriately.

Timing and Mode of Delivery

Delivery should be by 39 weeks. Birth trauma is more likely and although ultrasound prediction is imprecise, elective Caesarean section is often used where the estimated fetal weight exceeds 4 kg. During labour, glucose levels are maintained with a ‘sliding scale’ of insulin and a dextrose infusion.

The Neonate and Puerperium

The neonate commonly develops hypoglycaemia because it has become ‘accustomed to’ hyperglycaemia and its insulin levels are high. Respiratory distress syndrome occasionally occurs, even after 38 weeks. Breastfeeding is strongly advised. The dose of insulin can be rapidly changed to prepregnant doses.

Management of Diabetes

Preconceptual glucose control

Assessment of maternal diabetic complications

Patient education and team involvement

Glucose monitoring and insulin adjustment

Anomaly and cardiac ultrasound and fetal surveillance

Delivery by 39 weeks

Detection of and Screening for Gestational Diabetes

Screening Using Pre-Existing Risk Factors:

A previous large baby or unexplained stillbirth, a first-degree relative with diabetes, a body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2 or being of South Asian, Black Caribbean or Middle Eastern origin increase the risk. In the UK, NICE recommends that these women are screened using a 28 week GTT (75 g load). Women with PCOS [→ p.83] are also at risk. Those with previous gestational diabetes are also at risk and are screened at 18 weeks.

Screening Using Pregnancy Risk Factors:

where there is polyhydramnios or persistent glycosuria, a GTT is also indicated.

Universal screening may be introduced in the UK, although cost implications need to be considered.

Screening and Treatment of Gestational Diabetes

| Step1 a: | Universal screening (international consensus) |

| Perform 75 g GTT at 28 weeks (If previous history of gestational diabetes do at 18 weeks). If fasting >5.1 or 1 h later, >10.0, or 2 h later, >8.5, go to step 2 | |

| Step 1b: | OR…Risk-based screening (NICE 2008 recommendations) |

| If 1+ risk factors, perform GTT at 28 weeks. If fasting >7, or 2 h >7.8, go to step 2 | |

| Step 2: | Initial treatment |

| Give glucometer | |

| Advise re diet and exercise | |

| If after 2 weeks, levels >6, pre meals, or >7, 2 h after meals, go to Step 3 | |

| Step 3 | Oral hypoglycaemic drugs |

| If after 2 weeks, levels >6, pre meals, or >7, 2 h after meals, go to Step 4 | |

| Step 4: | Insulin |

| Treat as pre-existing diabetic |

Risk Factors for Gestational Diabetes

Previous history of gestational diabetes

Previous fetus >4.5 kg

Previous unexplained stillbirth

First-degree relative with diabetes

Body mass index (BMI) >30

Racial origin

Polyhydramnios

Persistent glycosuria

Management of Gestational Diabetes

The consensus criteria will lead to approx 16% of women being diagnosed with gestational diabetes in pregnancy. Most will not need insulin.

Diet:

Initially, women with an abnormal GTT should be given dietary and exercise advice and will monitor their glucose levels at home as with a pre-existing diabetic, but perhaps 2 days a week. Up to 20% will not achieve adequate control.

Oral hypoglycaemic agents such as metformin are increasingly used. In conjunction with diet and exercise, these will achieve control in up to 60% of women.

Insulin will be required in the rest, particularly where fasting glucoses are high. Management is as for pre-existing diabetics.

Postnatally, insulin is discontinued, but a glucose tolerance test should be performed at 3 months: >50% will be diagnosed as diabetic within the next 10 years.

Cardiac Disease

In pregnancy there is a 40% increase in cardiac output, due to both an increase in stroke volume and heart rate, and a 40% increase in blood volume. There is also a 50% reduction in systemic vascular resistance: blood pressure often drops in the second trimester, but is usually normal by term. The increased blood flow produces a flow (ejection systolic) murmur in 90% of pregnant women. The electrocardiogram (ECG) is altered during pregnancy: a left axis shift and inverted T-waves are common.

Epidemiology

Cardiac disease affects 0.3% of pregnant women. The incidence is increasing in the UK, because of immigration, and because more women with congenital disease are reaching reproductive age. The maternal risk is dependent on the cardiac status and most encounter no problems. However, acquired and uncorrected congenital disease mean that it is a major cause of maternal mortality, usually as a result of cardiac failure. Increased cardiac output acts as an ‘exercise test’ with which the heart may be unable to cope. This usually manifests after 28 weeks or in labour, but decompensation may also occur with blood loss or fluid overload. The latter can occur in the early puerperium, as uterine involution ‘squeezes’ a large ‘fluid load’ into the circulation.

Principles of Management

Patients with significant disease are preferably assessed before pregnancy. Some drugs, such as warfarin and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are contraindicated. Those with severe decompensated disease are advised against pregnancy. Cardiac assessment, particularly echocardiography, is needed. Fetal cardiac anomalies are more common (3%) and are best detected on ultrasound at 20 weeks’ gestation. Hypertension should be treated. Women who have conceived on contraindicated drugs will need to have these altered: care need to be individualized but beta-blockers are often used for hypertension. Thromboprophylaxis needs to be continued, but usually with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). Regular checks for anaemia are made. In labour, attention is paid to fluid balance; elective epidural analgesia reduces afterload. Elective forceps delivery helps avoid the additional stress of pushing in severe cases. Antibiotics in labour are recommended for some (e.g. replacement valves) to protect against endocarditis.

Types of Cardiac Disease and Their Management

Mild abnormalities such as mitral valve prolapse, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), ventricular septal defects (VSD) or atrial septal defects (ASD) do not usually cause complications.

Pulmonary Hypertension (E.g. Eisenmenger’s Syndrome):

Because of a high maternal mortality (40%) pregnancy is contraindicated and usually terminated.

Aortic Stenosis:

Severe disease (e.g. small valve area or large gradient) causes an inability to increase cardiac output when required and should be corrected before pregnancy. Beta-blockade is often used. Epidural analgesia is contraindicated in the most severe cases. Thromboprophylaxis is required for replaced aortic valves.

Mitral Valve Disease:

This should be treated before pregnancy. In the rare, severe cases of stenosis, heart failure may develop late in the pregnancy; beta-blockade is used. Artificial metal valves are particularly prone to thrombosis and warfarin is used after the first 12 weeks, despite its fetal risks.

Myocardial infarction is unusual in women of reproductive age; mortality is greater at later gestations.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a rare (1 in 3000) cause of heart failure, specific to pregnancy. It develops in the last month or first 6 months after pregnancy and in the absence of a recognizable cause. It is frequently diagnosed late. It is a cause of maternal death (risk 15%) and in more than 50% of cases leads to permanent left ventricular dysfunction. Treatment is supportive, with diuretics and ACE inhibitors. There is a significant recurrence rate in subsequent pregnancies.

Respiratory Disease

Tidal volume increases by 40% in pregnancy, although there is no change in respiratory rate. Asthma is common in pregnancy. Pregnancy has a variable effect on the disease: drugs should not be withheld, because they are generally safe and because a severe asthma attack is potentially lethal to mother and fetus. Well-controlled asthma has little detrimental effect on perinatal outcome. Women on long-term steroids require an increased dose in labour because the chronically suppressed adrenal cortex is unable to produce adequate steroids for the stress of labour.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy affects 0.5% of pregnant women. Seizure control can deteriorate in pregnancy, and particularly in labour. Epilepsy is a significant cause of maternal death and antiepileptic treatment is continued. However, the risk of congenital abnormalities (e.g. neural tube defects [NTDs]) is increased (4% overall), and this is largely due to drug therapy. The risks are dose dependent, higher with multiple drug usage and higher with certain drugs (e.g. sodium valproate). The newborn has a 3% risk of developing epilepsy.

Preconceptual Assessment is Ideal:

management involves seizure control with as few drugs as possible at the lowest dose, together with folic acid (5 mg/day) supplementation. Ideally, sodium valproate should be avoided because it is associated with a higher rate of congenital abnormalities and with lower intelligence (Neurol

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree