Fig. 72.1

Map of Oceania

72.1 Neonatal Services

Neonatal services providing ventilation in Australia and New Zealand range from being extremely centralized in some areas (e.g., Western Australia) to being more fragmented with many smaller units caring for larger populations (e.g., New South Wales). While there is some crossover between neonatal and pediatric intensive care, there is only one combined PICU/NICU in Australia and New Zealand.

There are 28 level III neonatal nurseries in Australia and New Zealand. Level III nurseries are those that care for ventilated babies. These nurseries are of varying size – King Edward Memorial Hospital in Western Australia has 105 cots which service the entire population of Western Australia, while, for example, Sydney Children’ Hospital (which also has PICU beds) has four cots. New South Wales with a population of six million is covered by nine neonatal units, while WA, with two million people, has one. New Zealand has six units widely spread across the country. While many of these units are attached to or part of maternity hospitals and hence receive most admissions directly from the delivery suite, others are part of pediatric hospitals and receive admissions directly from the emergency department or transport services. Approximately 8,000 babies were admitted to level III nurseries in 2006. This represents 2.2 % of all live births in Australia and New Zealand. Of these babies, 45.6 % were less than 32 weeks gestation. Almost all of these babies required some form of assisted ventilation, either invasive ventilation or CPAP. Overall 91.3 % of babies admitted to level III neonatal nurseries in Australia and New Zealand required assisted ventilation at some stage during their admission.

Of the 7,591 babies requiring assisted ventilation, 47 % required invasive ventilation, 76 % required noninvasive ventilation, and 6–7 % required high-frequency ventilation (HFV). Invasive ventilation, including HFV, was much more frequently used in babies of lower gestational ages, although even at gestational ages of 26–27 weeks, noninvasive ventilation was still commonly used (50 %) (Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network 2006).

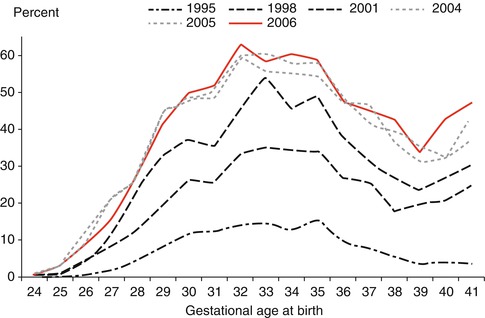

Trends over the last 10 years (Fig. 72.2) demonstrate that the use of CPAP has increased markedly.

Fig. 72.2

Trends in the use of CPAP as the only form of ventilation by gestational age (From Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network 2006, published with permission)

The use of HFV in babies born less than 28 weeks has been stable for the last 7 years after a dramatic increase in use in 1999. Since then, about 25–30 % of babies born less than 28 weeks gestation received HFV.

The use of inhaled nitric oxide however has continued to increase since 1997 with about 8 % of babies, both preterm and term, being given nitric oxide in 2006.

72.2 Pediatric Services

Pediatric critical care services in Australia and New Zealand are among the most centralized in the world. The entire pediatric population of Australia and New Zealand are serviced by eight full-time pediatric intensive care units across the country. Australia is divided up into seven states and territories, and each state/territory provides transport services to its region.

Over 8,000 children are admitted to intensive care each year in Australia and New Zealand, the majority being at eight full-time pediatric units. Of those patients, over half are mechanically ventilated on admission to intensive care. Although most children are cared for in dedicated PICUs, 14 general intensive care units also admit children throughout Australia and New Zealand. The median length of stay for mechanically ventilated patients was 2.17 days (Australian and New Zealand Paediatric Intensive Care Registry 2007).

In Australia, all major capital cities are serviced by a specialized PICU. In Tasmania, Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory; however, the population cannot sustain these stand-alone services, and children in these areas are either cared for in adult ICUs or transferred to PICUs in other areas. In New Zealand, the demographics are a little different in that only one city, Auckland, has a substantial enough pediatric population to maintain a stand-alone pediatric ICU. There are, however, a number of larger cities with substantial populations on both the north and south island of New Zealand, and children in these areas are generally cared for in adult ICUs or transferred to Auckland if tertiary pediatric critical care (e.g., cardiac surgery) is required.

The case mix requiring mechanical ventilation in Australia and New Zealand has altered over the past decade. Although the burden from some disease has probably lessened due to improving living conditions, better preventative measures against injury and infection and improved primary medical care, other conditions requiring mechanical ventilation have increased. More complex surgical procedures particularly surgery for congenital heart disease and more aggressive support of patients with chronic or progressive conditions have contributed to maintain the need for ventilatory support in children.

Of the children admitted to specialized pediatric intensive care units, over half are mechanically ventilated with ventilation rates ranging from 35 to 73 % in tertiary pediatric ICUs.

While there have been no surveys looking at mechanical ventilation in general, in Australia and New Zealand, the recently published lung injury survey looked at details of mechanical ventilation of children with acute lung injury in Australia and New Zealand over a 12-month period (Erickson et al. 2007).

In children with acute lung injury, the most common mode of ventilation was SIMV (51 %), followed by PRVC (20 %). High-frequency oscillation was the initial mode used in 12 % of patients with ALI but was used in 29 % of these patients during their admission in ICU.

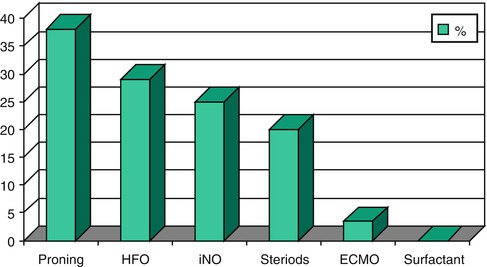

In patients with ALI, the use of adjuncts to mechanical ventilation was consistent in all units in the region and is shown in Fig. 72.3.