20 Oral Disorders

Assessment Techniques

Key elements of the oral/dental history include the following:

1 Timing of eruption and exfoliation of primary teeth, timing of eruption of permanent teeth, and any problems encountered

2 Brushing and flossing frequency and technique

3 Dietary habits including frequency of bottle-feeding and breast-feeding in infancy; whether infants and toddlers are put to bed with a bottle; time of weaning; frequency of carbohydrate intake; and possible symptoms of eating disorders in adolescence

4 Current source of dental care and frequency of visits

5 Current history of symptoms: oral pain, redness, swelling, drainage, headaches, abdominal pain, decreased appetite (especially for chewy foods)

6 Problems with bite or occlusion

7 History of dental problems and/or orofacial trauma and their treatment

3 Occlusion (bite) and tooth alignment

4 Mandibular excursion in lateral, vertical, and anterior/posterior planes

5 Integrity of enamel, presence of caries

6 Appearance of gingivae from both labial-buccal and lingual sides

7 Condition of the other oral soft tissues: tongue, palate, mucobuccal folds, and sublingual spaces

Successful examination requires close visual inspection of the face; palpation of suspected areas of abnormality; and systematic inspection of the dentition, its supporting structures, and the oral soft tissues. This can be challenging with young children, but patience and a gentle, even playful manner can be of great help. At least initially, young children should be allowed to sit on the parent’s lap. Toys, puppets, and a rubber glove blown up into a balloon can serve as useful distractions. Drawing a face on a tongue depressor and giving it to the child to hold, as well as letting the child look in the dental mirror, are good ways to introduce these basic instruments and make them less threatening. If an otoscope is being used as a light source in a medical office setting, letting the child “blow out the light” is another good introductory game, as is demonstrating the examination on the parent or examiner. Then the examiner can gradually begin the hands-on assessment. In younger children, a “lap exam” may be a useful way to examine an apprehensive child (Fig. 20-1). The parent places the child in their lap, facing them, and the child’s head reclines into the examiner’s lap. It is important to have the parent hold the child’s hand during the examination. A lap examination is not advised if the mother is pregnant, as the child may accidentally kick the mother. If cooperation cannot be achieved despite these measures, immobilization in a papoose board may be necessary. With older children, examination of the patient in the supine or semirecumbent position with good lighting assists visualization and may be more practical.

Normal Oral Structures

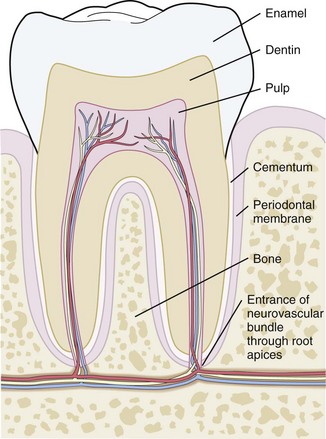

To assist understanding of this chapter and communication when consulting dentists, a review of basic terminology is in order. Each tooth is composed of an outer protective enamel layer; an inner layer of dentin consisting of tubules, which are thought to serve a nutritional function; and a central neurovascular core termed the pulp. The roots of the teeth are anchored in the sockets of the alveolar processes of the mandible and maxilla by an encompassing periodontal membrane or ligament. The neurovascular supply to the root apex also passes through this structure. The bony processes between the teeth are referred to as the interdental septae (Fig. 20-2).

Primary Dentition

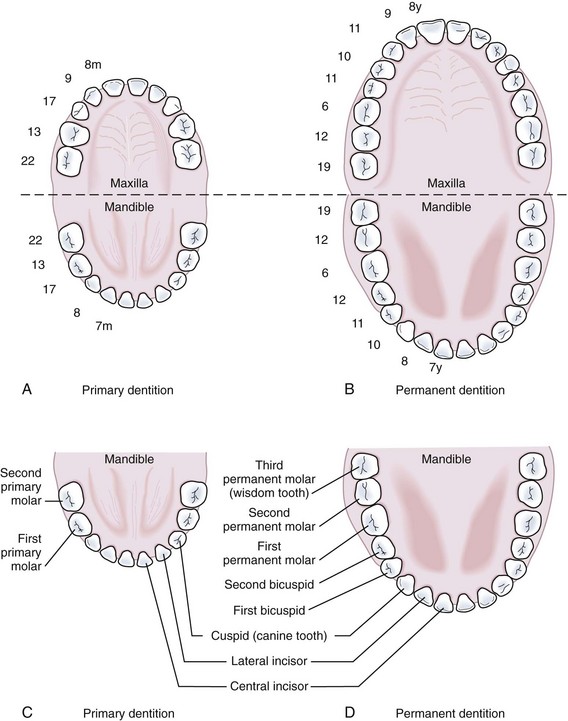

Development of the alveolar bone is directly related to the formation and eruption of teeth, and normal patterns of dental development occur symmetrically. Eruption times and sequence may be extremely variable, but typically at approximately 6 months of age, the mandibular central incisors erupt. This stage is often preceded by a period of increased salivation, local gingival irritation, and irritability. These symptoms may vary in intensity, but they respond well to oral analgesics and usually subside when the primary tooth erupts into the oral cavity. Other symptoms such as fever or diarrhea have never been proven to be directly related to teething. The lower incisors are soon followed by the maxillary central incisors and the maxillary and mandibular lateral incisors (Fig. 20-3). By the end of the first year, all eight anterior teeth are usually visible. At 2 years, all primary teeth have erupted with the exception of the second primary molars, which erupt shortly thereafter. By the age of 3 years, the full primary dentition is typically present and functional (Fig. 20-4).

Figure 20-3 Early primary dentition. The mandibular and maxillary central and lateral incisors are the first to erupt.

During most of the primary dentition stage, the gingiva appears pink, firm, and not readily retractable. A well-defined zone of firmly attached keratinized gingiva is present, extending from the bottom of the gingival sulcus to the junction of the alveolar mucosa. Rarely, local irritation may develop into acute or subacute pericoronitis, with elevated temperature and associated lymphadenopathy (see Fig. 20-50). Topical and/or systemic therapy may be required for treatment; however, lancing the gingiva to relieve such symptoms is not usually indicated.

Mixed Dentition

The mixed dentition stage of development begins with the eruption of the first permanent molars at about 6 years of age and continues for approximately 6 years. During this period, the following teeth erupt from the gums in sequence: mandibular central incisors, maxillary central incisors, mandibular lateral incisors, maxillary lateral incisors, mandibular cuspids, maxillary and mandibular first premolars, maxillary and mandibular second premolars, maxillary cuspids, and mandibular and maxillary second molars (Fig. 20-5).

The mixed dentition during this stage undergoes certain physiologic changes including root resorption followed by exfoliation of primary teeth, eruption of their successors, and eruption of the posterior permanent teeth. During the period of root resorption of primary teeth, and for several months after the eruption of permanent teeth, the teeth are relatively loosely embedded in the alveolar bone and more vulnerable to displacement by trauma. Other minor complications may occur during resorption and exfoliation of primary teeth and eruption of permanent teeth. Gingival irritation can occur as a result of increased mobility of primary teeth but usually disappears spontaneously when the tooth is lost or extracted. Two transient deviations of eruption pattern may occur: the mandibular incisors may erupt in a lingual position behind the primary incisors (“double teeth”) (Fig. 20-6), and the maxillary incisors may assume a widely spaced and labially inclined position (“ugly duckling” stage). Finally, the occlusal surfaces of newly erupted permanent teeth are relatively “rough” (see Figs. 20-5 and 20-43), assisting plaque accumulation that increases the risk of staining, gingivitis, and formation of caries.

Early Permanent Dentition

The stage of early permanent dentition marks the beginning of a relatively quiescent period in dental development. Activities are limited to root formation of a few permanent teeth and the calcification of the third molars. By this time the length and width of the dental arches are well established (Fig. 20-7); however, the jaws undergo a major growth spurt during puberty that alters their size and relative position. The gingiva begins to assume adult characteristics, becoming firm and pink in color, with an uneven, stippled surface texture and a thin gingival margin. Puberty is occasionally associated with gingivitis, thought to be secondary in part to hormonal changes (Fig. 20-8). The gingivae become mildly edematous and erythematous and bleed with brushing (the common chief complaint). Inattention to careful dental hygiene may also contribute to development of this disorder, which necessitates good oral hygiene for control.

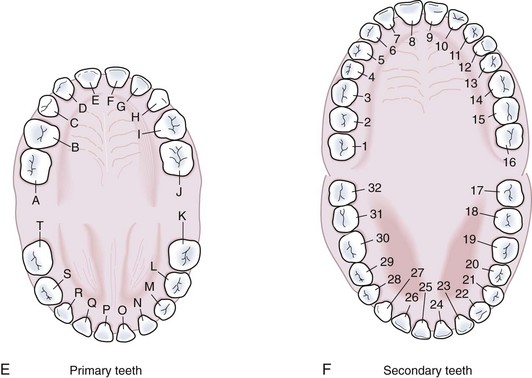

In Figure 20-9 the primary and permanent dentition are presented diagrammatically.

Harmful Oral Habits

Thumb and Finger Sucking

Children often develop sucking habits, using the thumb, finger(s), or objects. Thumb and finger sucking begins antenatally and is considered a normal behavior pattern. However, if the habit persists beyond the late primary dentition stage of dental arch development (5 years), the extrinsic forces applied by the sucking action can produce pathologic changes in the child’s normal arch growth. These deviations range from minor, reversible changes to gross malformations in the dental arches that produce significant anterior open bites and/or posterior crossbites. The degree of change depends on the duration, frequency, and intensity of the sucking habit (Fig. 20-10).

Bottle and Pacifier Habits

The forces produced by prolonged use of bottles and pacifiers can first cause dental malocclusions and may, if the habit persists, worsen the resulting deformity with the involvement of adjacent jaw structures. Usually, if the child is weaned from the bottle and pacifier by the age of 12 months, no permanent changes in bite development can be expected. The longer any force is applied, however, the greater the risk that the distortion in the dental arches and adjacent bony structures will not self-correct (Fig. 20-11).

Thus the use of bottles and pacifiers should be discouraged by the age of 12 months. After this age, changes in the oral structures have been noted with prolonged use and are more likely to be permanent. Counseling parents during the neonatal period not to put their infants to bed with a bottle, but rather to hold them during all feedings, is probably one of the best ways to prevent later difficulties with weaning. Such practices also prevent the development of nursing bottle caries (see Fig. 20-42).

Natal and Neonatal Abnormalities

Teeth

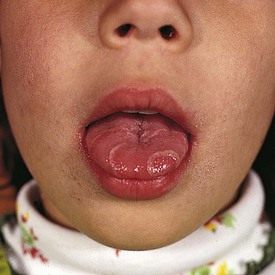

Teeth that are present in the oral cavity at birth are called natal teeth, whereas those erupting during the neonatal period (30 days after birth) are called neonatal teeth. The incidence of natal teeth has been reported to be approximately 1 in 2000 births. Although seen in normal infants, this anomaly is more frequent in patients with cleft palate (Fig. 20-12) and is often associated with the following syndromes: Ellis-van Creveld syndrome, Hallermann-Streiff syndrome, and pachyonychia congenita. The majority, about 90%, of such teeth are true primary teeth, but occasionally they are supernumerary. Some are abnormal, with either hypoplastic defects or poor crown or root development. Natal teeth may cause feeding problems for both the infant and mother. Ulceration of the ventral surface of the tongue by sharp tooth edges (Riga-Fede disease) may develop if natal teeth remain in the oral cavity. This condition is usually transient, but in persistent cases symptomatic treatment or extraction of such teeth may be indicated. Most normal-appearing natal teeth can be retained, but those that are supernumerary, abnormal, or very loose may have to be removed.

Gingival Cysts in the Newborn

1 Epstein pearls are keratin-filled cystic lesions lined with stratified squamous epithelium. They appear as small, white lesions along the midpalatine raphe and contain no mucous glands (Fig. 20-13).

2 Bohn nodules are mucous gland cysts, often found on the buccal or lingual aspects of the alveolar ridges and occasionally on the palate. They are multiple, firm, and grayish white in appearance. Histologically they show mucous glands and ducts (Fig. 20-14).

3 Dental lamina cysts are found only on the crest of the alveolar mucosa. Histologically, these lesions are different because they are formed by remnants of dental lamina epithelium. They may be larger, more lucent, and fluctuant than Epstein pearls or Bohn nodules and are more likely to occur singly (Fig. 20-15).

Figure 20-13 Gingival cysts. The small, whitish cystic lesions seen along the midpalatine raphe are called Epstein pearls.

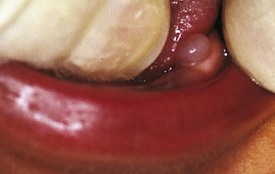

Congenital Epulis in the Newborn

Congenital epulis is a benign, soft tissue tumor seen on the alveolar mucosa at birth or shortly after. It is usually found on the anterior maxilla as a pedunculated swelling (Fig. 20-16) but may appear on the mandible or occasionally on both jaws. The mass is firm on palpation, and the overlying mucosa appears normal. Histologically, sheets of large granular cells are seen. Differential diagnosis should include rhabdomyoma and melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy. The lesion is amenable to conservative surgical excision, and recurrence is infrequent.

Melanotic Neuroectodermal Tumor of Infancy

Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy is a benign yet aggressive tumor, developing during the first year of life and often found on the anterior maxilla in association with unerupted or erupted teeth. It often bulges and destroys the alveolar bone, thus displacing the associated primary tooth. The tumor mass is grayish blue, firm on palpation, and spherical in shape (Fig. 20-17). Careful surgical removal is effective, and recurrence is unusual.

Developmental Abnormalities

Soft Tissue Abnormalities

Geographic Tongue (Benign Migratory Glossitis)

Geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis) is a painless condition characterized by inflamed, irregularly shaped areas on the dorsum of the tongue that are devoid of filiform papillae. Lesions are red, slightly depressed, and bordered by a whitish band (Fig. 20-18). Spontaneous healing followed by the formation of similar lesions elsewhere on the tongue results in a migrating appearance. The etiology is unknown; however, a strong association with stress and allergies is suspected. Although benign, the course of this disorder may be prolonged for months, and it may recur.

Abnormalities of the Frenula

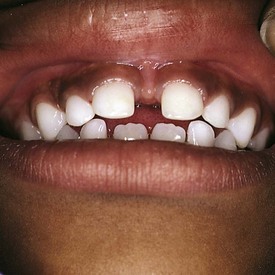

During embryonic life, the maxillary labial frenulum extends as a band of tissue from the upper lip over and across the alveolar ridge and into the incisive (palatine) papilla. Postnatally, as the alveolar process increases in size, the labial frenulum separates from the incisive papilla and becomes relatively smaller. With the eruption of primary and later permanent teeth, the frenulum attachment moves apically and further atrophies as a result of vertical growth of the alveolar process. The developmental gap (diastema) between the maxillary central incisors tends to close with the full eruption of the maxillary permanent canines. On occasion the maxillary frenulum fails to atrophy and the diastema persists (Fig. 20-19). The mandibular midline frenulum only rarely maintains a lingual extension and therefore only rarely causes a diastema between the mandibular central incisors.

Figure 20-19 Large diastema (excessive spacing) between the front teeth secondary to an inferiorly positioned maxillary frenulum.

The lingual frenulum extends almost to the tip of the tongue in early infancy and then gradually recedes. On occasion, ankyloglossia (tongue tie) is seen (Fig. 20-20), but this is rarely associated with feeding or speech difficulties. Various surgical procedures have been advocated to correct this condition. In general, frenulectomy is seldom indicated and should be recommended only after appropriate justification. Congenital anomalies may include an enlarged frenulum, labiolingual frenulum extensions, or supernumerary frenula as seen in orofaciodigital syndrome (Fig. 20-21).

Gingival Hyperplasia

Phenytoin-induced Gingival Hyperplasia

The administration of phenytoin over a period of time frequently causes generalized hyperplasia of the gingiva (Fig. 20-22, A and B). The gingiva may become secondarily inflamed, edematous, and boggy, especially if proper oral hygiene is not practiced. The severity is often related to the degree of local irritation, stemming from poor oral hygiene, mouth breathing, caries, or poor occlusion (alignment). Because hyperplasia tends to recur after surgical excision, gingivectomy is usually reserved for those patients whose overgrowth interferes with function and for those whose therapy has been discontinued.

Eruption Cysts (Eruption Hematoma)

An eruption cyst is a fluid-filled swelling, nontender in the majority of cases, over the crown of an erupting tooth. When the follicle is dilated with blood, the lesion takes on a bluish color and is termed an eruption hematoma (Fig. 20-23). Although the eruption cyst is a superficial form of dentigerous cyst, it rarely impedes eruption. Surgical exposure of the crown is seldom necessary. Rarely, such a cyst may become secondarily infected. In such cases, patients complain of headache or facial pain and the cyst is tender on palpation. Incision and drainage are required typically when infection has developed.

Mucocele and Ranula

A mucocele is a painless, translucent or bluish lesion of traumatic origin, most often involving minor salivary glands of the lower lip (Fig. 20-24). The lesion may alternately enlarge and shrink. The treatment of choice is surgical excision of the lesion and the associated minor salivary gland.

Figure 20-24 A mucocele on the lower lip, with the characteristic translucent coloration secondary to fluid retention.

A simple ranula is a retention cyst in the floor of the mouth that is confined to sublingual tissues superior to the mylohyoid muscle. It appears clinically as a bluish, transparent, thin-walled, fluctuant swelling (Fig. 20-25). Herniation of the ranula through the mylohyoid muscle results in a cervical or plunging ranula that becomes more apparent in the oral cavity with the muscle contraction associated with jaw opening. Simple incision and drainage of the ranula is not an acceptable treatment because healing is followed by recurrence. Marsupialization by suturing the edges of the opened cystic wall to the mucous membrane is the recommended treatment. The plunging ranula must be removed in its entirety along with the associated salivary gland to avoid recurrence.

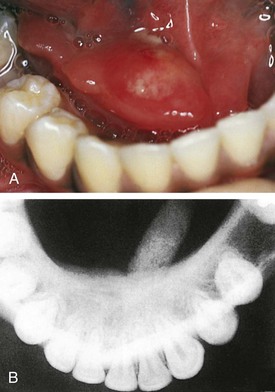

Salivary Calculus (Sialolithiasis)

Formation of a salivary calculus is rare in the pediatric population, but when it does occur it may affect either the Wharton duct or Stensen duct (Fig. 20-26, A). Partial obstruction of the duct results in pain and enlargement of the gland, especially at mealtime. Although palpation of the stone may be possible, dental radiographs confirm the diagnosis and give appropriate information about its size and location (Fig. 20-26, B). Larger salivary stones wedged within the ducts may cause localized irritation and secondary infection. If the calculus cannot be manipulated through the duct, surgical intervention may be necessary.

Hard Tissue Abnormalities

Hyperdontia and Hypodontia

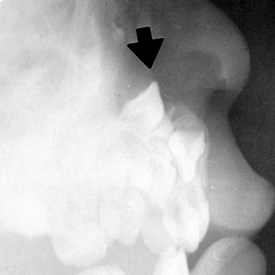

Variations in tooth number include both hyperdontia and hypodontia. Supernumerary teeth occur in about 3% of the normal population, but patients with cleft lip and/or cleft palate and cleidocranial dysplasia have a significantly higher incidence. The most common site is the anterior palate (Fig. 20-27). Supernumerary teeth may have the size and morphology of adjacent teeth or may be small and atypical in shape. They may erupt spontaneously or remain impacted. Early consideration of removal is justified because of complications such as impeded eruption, crowding, or resorption of permanent teeth; cystic changes; or ectopic eruption into the nasal cavity, the maxillary sinus, or other sites (Fig. 20-28).

Figure 20-27 Hyperdontia. Erupted supernumerary tooth lingual to the maxillary central incisor in the deciduous dentition.

Congenital absence of teeth is more often seen in the permanent dentition than in the primary. Most frequently missing are third molars, second premolars, and lateral incisors. Hypodontia is frequently associated with several ectodermal syndromes such as anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia and chondroectodermal dysplasia (Fig. 20-29).

Alterations in Tooth Size and Shape

Teeth that are smaller or larger than normal are termed microdonts and macrodonts, respectively. These teeth are genetic anomalies. They are clinically significant when a discrepancy in tooth size and dental arch length results in severe crowding or spacing of the teeth. Size abnormalities are often localized to one tooth or to a small group of teeth (Fig. 20-30).

Variations in shape also result from the joining of teeth or tooth buds. Fusion is the joining of two tooth buds by the dentin. Concrescence is the joining of the roots of two or more teeth by cementum. Gemination (twinning) results from the incomplete division of one tooth bud, resulting in a large crown with a notched incisal edge and a single root (Fig. 20-31).

Hypoplasia and Hypocalcification

Numerous local and systemic insults are capable of causing the enamel defects of hypoplasia and hypocalcification. The most common etiologic factors are local infection such as an abscessed primary tooth, which, when not diagnosed and treated promptly, may damage the enamel of its developing permanent counterpart. Other causes include systemic infections with associated high fever, trauma (such as intrusion of the primary tooth), and chemical injury, of which excessive ingestion of fluoride is an example. Other etiologic factors include nutritional deficiencies, allergies, rubella, cerebral palsy, embryopathy, prematurity, and radiation therapy. Hypocalcification results from an insult during mineralization of the tooth and is seen as opaque, chalky, or white lesions (Fig. 20-32). Hypoplasia results from an insult during active matrix formation of the enamel and clinically manifests as pitting, furrowing, or thinning of the enamel (see Fig. 20-33).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree