Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity and musculature. These ectopic endometrial implants can occur anywhere in the body but are usually found in the pelvis. Endometriosis has a wide spectrum of symptoms. Women usually present with pelvic pain, with severity of the pain ranging from minimal to debilitating, dyspareunia, and infertility. They may present with a pelvic mass. Endometriosis is a chronic, estrogen-dependent disorder that can have a profound impact on a woman’s life affecting her physical, emotional, and social well-being.

The actual prevalence in the population is unknown, but it is estimated to be about 6 to 10% of reproductive age women in all ethnic and social groups.

1 The prevalence of pelvic endometriosis is 1% in women undergoing major surgery for all gynecologic indications and 30 to 60% in women undergoing diagnostic laparoscopy for pelvic pain.

2,

3,

4 Approximately two-thirds of teenagers undergoing laparoscopy for pelvic pain not responsive to treatment have endometriosis.

5 One-third of women undergoing laparoscopy for infertility are found to have endometriosis.

6 In the United States in 2002, the direct treatment cost of endometriosis was around $18.8 billion, and combination of direct and indirect cost was $22 billion.

7

PATHOGENESIS

Multiple theories have been proposed to explain the histogenesis of endometriosis.

6 No one theory can explain the pathogenesis completely, and it is possible that more than one source or pathway leads to the development of endometriosis. The most widely accepted theory is retrograde menstruation or implantation theory, also known as Sampson theory, where endometrial fragments shed during menstruation are transported retrograde through the fallopian tubes and then implant in the pelvis. The direct transplant theory explains the development of endometriosis in a scar after cesarean section, vaginal repair, or other pelvic surgery. The coelomic metaplasia theory is derived from the embryologic basis that all pelvic organs develop from the spontaneous or induced metaplastic change in mesothelial cells that line the coelomic (peritoneal) cavity. It proposes that the lining of the abdominal cavity contains undifferentiated cells with the ability to differentiate into endometrial cells. Evidence also indicates that endometriosis can spread outside the pelvis through vascular and lymphatic channels.

Anatomy, altered immunity, and genetics influence the development of endometriosis. Anatomic differences in the pelvis, which increase reflux through the fallopian tubes, increase the chance of endometriosis. For example, endometriosis has a higher incidence in females with müllerian anomalies, which result in outflow tract obstruction.

8 However, women with endometriosis do not have a higher incidence of retrograde menstruation compared to women without endometriosis. Although almost all women have retrograde menstruation, not all women develop the disease. The development of endometriosis may depend on alterations in the immune response that recognizes and eliminates refluxed endometrial fragments as well as increased ability of the ectopic endometrial cells to adhere and invade into the peritoneal cavity or other surfaces.

9,10 Endometriotic implants are associated with an increased production of cytokines, prostaglandins, and growth factors, which lead to increased proliferation of ectopic implants, enhanced local angiogenesis, and the attraction of leukocytes to the sites of inflammation.

11 Genetics may also play a role in the development of endometriosis. The first-degree relatives of women with endometriosis have a 7% likelihood of developing or having the disease compared to a 1% likelihood in unrelated women.

12 Numerous studies have looked for specific genes that predispose to the development of endometriosis, but the exact genetic cause is unclear.

13The stem cell theory of endometriosis centers on the idea that mesenchymal stem cells that are derived from bone marrow can differentiate into endometrium and endometriosis.

14 There is evidence that in women who have undergone bone marrow transplants, the endometrium in these women contains a substantial number of donor-derived endometrial cells.

14 It is possible that stem cells that are derived from the bone marrow (even in women who have not been given a bone marrow transplant) reside in the endometrium and may reflux during retrograde menstruation and cause

endometriotic implants just as endogenous endometrial cells may. Further evidence demonstrates that endometriotic implants are populated by bone marrow-derived stem cells. This stem cell theory would also explain cases of endometriosis at sites outside the peritoneal cavity; endometriosis at distant sites may arise from stem cells.

Women with endometriosis also have an increased risk of malignancy and autoimmune diseases. One study of women discharged from the hospital with a diagnosis of endometriosis suggested an increased risk of developing breast, ovarian, and hematopoietic cancers in the future.

15 Rarely, adenocarcinoma may also develop from endometriotic implants.

16 Endometriosis and ovarian cancer share certain risk factors such as early menarche (before age 11 years), shorter cycle lengths (less than 27 days), and lower parity.

17 Studies show that the relative risk of ovarian cancer appears to be increased in women with a long history of endometriosis, although the magnitude of the increased risk is not clear.

18,19 The risk of ovarian cancer appears to be highest for women with endometriosis and primary infertility, although this risk may be reduced with the use of oral contraceptive pills.

20,21 Screening women with endometriosis for ovarian cancer is not recommended however because the incidence is low, and importantly, there is no effective screening test. There is also no evidence that removing sites of endometriosis will decrease the risk of ovarian cancer.

Autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus along with hypothyroidism, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and asthma are also more common in patients with endometriosis.

22

PATHOLOGY

Endometriosis is most commonly found in the ovaries, followed by the anterior and posterior cul de sac, posterior broad ligaments, uterosacral ligaments, uterus, fallopian tubes, and round ligaments. Both ovaries are involved in about 33% of cases. The left side of the pelvis and left ovary are more frequently affected than the right, possibly because the presence of the sigmoid colon decreases peritoneal fluid movement. Gastrointestinal involvement is the most frequent extragenital site of endometriosis, occurs in 5% of cases, and most commonly affects the sigmoid colon.

23 The urinary tract is the third most commonly involved system with superficial endometriotic lesions found in the bladder, followed by the ureter. Other less common sites include the cervix, vagina, cecum, ileum, umbilicus, and inguinal canals. Rare cases have found endometrial implants in the lung, diaphragm, breast, pancreas, liver, gallbladder, kidney, urethra, vertebrate, bone, nervous system, and extremities.

6Microscopically, endometriosis has the characteristics of the uterine endometrium including glands and stroma. The endometriotic lesions also contain fibrosis, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, and blood. The lesions can be superficial or invasive into the ovary or retroperitoneum.

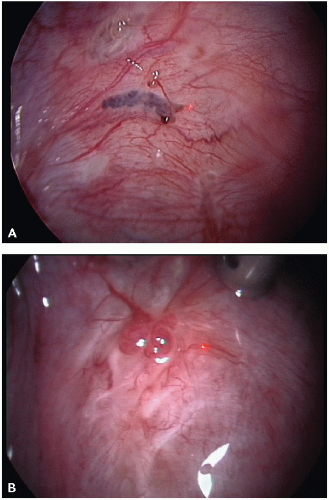

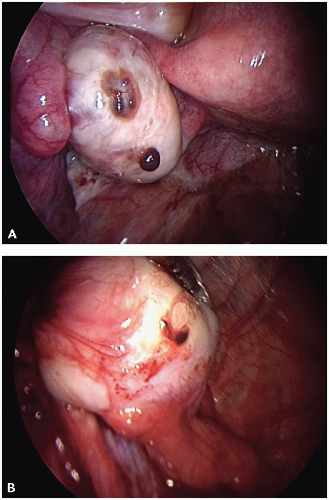

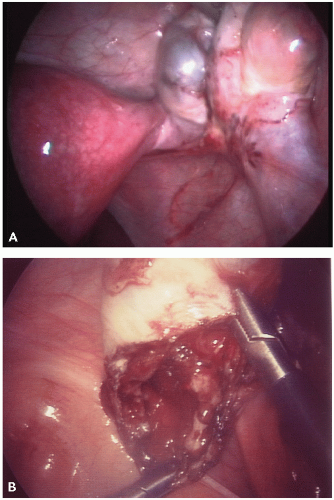

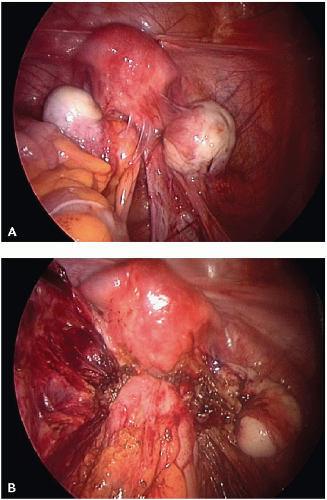

The visual appearance and size of endometrial lesions is extremely variable. Lesions can appear as the bluish black “powder burn” lesions due to the hemosiderin deposits and as whitish opacifications, translucent blebs, raised flame-like patches, or reddish/reddish blue irregularly shaped islands. These lesions are often seen with peritoneal surfaces that appear scarred (see

Figs. 10.1,

10.2,

10.3 through

10.4 for pictures of endometriosis).

Ovarian implants can present superficially or as cystlike structures called endometriomas. Endometriomas, often referred to as chocolate cysts, contain blood, fluid, and endometrial fragments. They are frequently densely adherent to nearby structures.