Americans With Disabilities Act Requirements and Incentives

Passed in 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is the landmark civil rights legislation intended to eliminate discrimination against individuals with disabilities. Its four titles apply to employers, public and private entities and telecommunication services, and require these covered entities to provide equivalent access to programs and services to people with disabilities. Health care providers are most impacted by Title III of the ADA, which mandates certain accommodations in private entities. Title III requires places of public accommodation, including professional offices of health care providers, to reduce environmental barriers by modifying physical access if such modifications are readily achievable. The ADA spells out particular architectural accessibility requirements for buildings constructed after 1992 (http://www.ada.gov/stdspdf.htm). Older buildings may be required to renovate or retrofit in order to be in compliance, if such renovations can be reasonably accomplished. Any facility that is undergoing extensive remodeling is required to include accessibility features as specified in the Act and its

regulations. Owners of buildings in which offices are leased may be responsible for access improvements under the law in some cases. Whether removal of a physical barrier is readily achievable or not is judged on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the cost of the modification and the financial resources of the covered entity, among other things. Tax credits and incentives are available for businesses that incur expenses for removal of barriers or improving access to persons with disabilities (see http://www.ada.gov/archive/taxpack.htm for details).

The ADA requires accommodations beyond physical space alterations, for example, by prohibiting discrimination against persons with disabilities in the form of restrictive actions or policies. Under the ADA, exclusion, segregation, or unequal treatment of individuals with disabilities is not permitted. Thus, denial of service to a woman because of her disability is prohibited. Similarly, women with disabilities cannot be denied equal opportunity to access services, for example, by a policy requiring a driver’s license for identification. Individuals with disabilities cannot be required to receive services in a segregated location (e.g., entry through a back door or waiting in a separate waiting room), unless such a location or arrangement is the only accessible means for her to receive services.

Covered entities are also required by the ADA to provide auxiliary aids and services necessary to ensure equal access to services to individuals with disabilities that substantially limit the ability to communicate, such as vision, hearing, or speech impairments. Auxiliary aids and services sufficient to ensure effective communication are required at the covered entity’s expense; the type of aid or service required depends on the length and complexity of the communication involved. A common situation to which this provision applies is the requirement for covered entities to provide a qualified sign language interpreter for an individual with a hearing impairment who communicates using sign language and must discuss complex medical information with a health care provider. Other examples include Braille and largeprint reading materials, or reading a patient information pamphlet, consent form, or bill aloud to a woman with low vision. Providers are encouraged to consult directly with women with disabilities to determine what type of aid or service will ensure effective communication.

The nondiscrimination requirements of the ADA are not limitless. Entities may raise a number of key defenses to a charge of discrimination under the ADA. Failure to provide an accommodation may be defensible if (a) provision of the accommodation would fundamentally alter the nature of services provided by the entity; (b) providing the accommodation would cause the entity undue burden, defined as “significant difficulty or expense”; or (c) providing the accommodation would cause a direct threat to others. In each case, the entity accused of discrimination bears the burden of showing that failure to provide the accommodation meets the defense standard; this is judged on a case-by-case basis. Details on the requirements and limitations of ADA Title III are discussed in the ADA Title III Technical Assistance Manual (http://www.ada.gov/taman3.html).

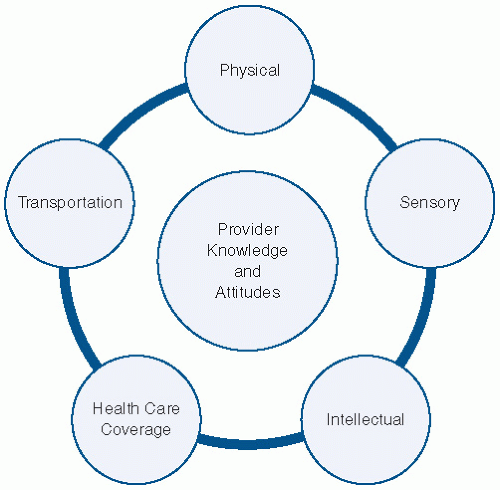

Physical Access

Office practices must ensure adequate physical access for women with disabilities, from parking, to building and office entryways, to waiting areas, reception counters, restrooms, hallways, and examination rooms.

10 Growing attention is being given to the concept of universal design in the built environment, in which facilities are designed to be inherently accessible and usable by the maximum number of individuals, regardless of ability.

11Improving access in the office will serve not only to make a woman’s visit more comfortable, it will allow the provision of better care. In some cases, substantial structural remodeling may be needed, but other simple steps and modifications to office procedures can simplify a woman’s visit. Offices can improve access for women with disabilities by the following:

Ensuring that there is at least one reserved accessible parking space and that there is a safe and barrier-free (i.e., no curbs or steps) path between the parking space and entrance.

Installing ramps to overcome architectural barriers. Ramps may be purchased or built and must include 12 inches of length for every 1-inches increase in elevation.

Enlarging door widths to at least 30 inches; 32- to 36-inches doorways are ideal.

Removing or adapting doorway thresholds that are not flush with the floor.

Ensuring that trash cans, plants, or other items do not block elevator call buttons.

Locating a building directory so it is visible from wheelchair height; using a font large enough to be read by people with vision impairment.

Installing a power door opener or a doorbell for use by people who cannot open a door independently.

Exchanging round doorknobs with “lever” door handles.

Having at least a portion of the reception desk lowered to wheelchair height.

Mailing long medical history and other intake forms to patients in advance.

Training reception staff to come around the desk to assist patients with check in, especially if the reception desk is not lowered. Offering assistance with completing forms in a private location.

Preserving a space for a wheelchair in the waiting area.

Clearing boxes, equipment, or other items from office hallways.

Allowing flexibility in scheduling to accommodate late arrivals related to transportation difficulties. Scheduling longer appointments to accommodate patients’ additional needs (e.g., assistance with forms,

undressing or transfer assistance, communication through an interpreter).

Inviting women with disabilities to assess office layout and practices and make suggestions for improvement.

Communication

Providing quality primary and preventive care relies heavily on communication; this is especially so for care visits for women with disabilities. Practitioners and staff should avail themselves of the expertise each woman with a disability holds about her condition, her specific needs, and how those needs can be addressed. Asking a woman questions about her disability and how she believes it may relate to any health concerns is not only greatly informative, but it demonstrates respect and that her input is valued.

10Barriers to effective communication need to be addressed. Women with hearing impairments may choose to communicate in one or more of a number of ways, including American Sign Language, other manual signs, speech-reading (or lip reading), or cued speech (a combination of speech reading and hand cues). Clinicians should ask women who are deaf or hard of hearing how they would prefer to communicate and then comply with that preference

12 with flexibility and adapting to the needs of the situation.

8

Assistance and Accommodation

One of the first accommodations a woman with a disability may require for a quality gynecologic office visit is time. Additional assistance and support in the office and examination room are frequently needed, ranging from help completing paper-based history and insurance forms, assistance with undressing, transfer to the examination table, completion of a pelvic examination, or discussing a management plan through a sign language interpreter. Scheduling staff can facilitate quality care by asking new patients if they will need any special assistance during their office visit, and adjusting appointment length accordingly.

Plan to perform the patient’s history and physical examination in the largest, most accessible room or rooms possible, keeping in mind the width of hallways and doors. Practicing the steps needed to provide a competent and successful office encounter can ensure that when women with disabilities present for care, their experience is as comfortable as possible.