Office-Based Procedures

Silvia T. Linares

Jenny J. Duret

Office-based procedures have been an integral part of the gynecologic practice. Colposcopy, cervical and vaginal biopsies, and intrauterine devices insertion are done in the office since their inception more than 50 years ago. The increment in office procedures probably corresponds to better reimbursements, greater satisfaction for patients and physicians, and a safe and efficient way to provide a service.1 Patients have better scheduling options, a known environment within the office, and can avoid the hassle of going to a hospital or a surgery center to have a procedure done. For doctors and their staff, the advantages are clear: control of costs and sense of doing something innovative with better time management.1,2,4 In 2013, the Joint Commission established the national patient safety goals for the ambulatory health care accreditation program. Some of those goals are very relevant to the implementation of an office-based procedure program. For example2,3:

Goal 1 improves the accuracy of patient identification. (Use at least two patient identifiers.)

Goal 2 improves the safety of medication use. (Label all medications, medications containers, and other solutions on and off the sterile field in perioperative and other procedural settings; maintain and communicate accurate patient medication information.)

Goal 7 reduces the risk of health care-associated infections (hand hygiene guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] or the World Health Organization [WHO].)

The introduction of the universal protocol for preventing wrong site, wrong procedure, specifically:

Conduct a preprocedure verification process. In gynecology, a written diagram can be used with the patient because it is anatomically impossible or impractical to mark the site.

A time out is performed before the procedure.3

OFFICE SET UP

Make sure that the room assigned is in compliance with the fire, occupational safety, and health administration codes; has all the necessary equipment to supply the level of anesthesia needed or chosen instruments such as a pulse oximeter, blood pressure and pulse heart rate monitors, reliable oxygen source, resuscitation equipment including defibrillator, cardiac monitor, auxiliary electrical power source; and that the equipment used for the procedures has been serviced, tested, and inspected.2,5, 6, 7

With the increase in office-based procedures, it is imperative to have a safe practice. It is preferable to have a special room and identified staff dedicated to the offered procedures. Depending on the type of practice (solo vs. group), a responsible practitioner needs to ensure the creation of protocols, checklists, and policies within the practice that will assure the success of more invasive and technological difficult procedures.5

PAIN MANAGEMENT FOR OFFICE PROCEDURES

Pain management is the most challenging component of a successful office procedures program. Have in mind that patient selection and experience will probably overcome this obstacle. There are different levels of anesthesia (pain control)6,8,9:

Level 1: local anesthesia with minimal or no preoperative oral anxiolytic medication

Level 2: moderate sedation

Level 3: deep sedation or general anesthesia

Level 1 (local anesthesia with minimal or no sedation) is the recommended level for the majority of the office procedures described in this chapter, but have in mind

that level 2 is an option in the office setting if you can have an anesthesiologist present during the procedure or there is a non-anesthesiologist with training to provide deep sedation or general anesthesia in your practice.8,9

that level 2 is an option in the office setting if you can have an anesthesiologist present during the procedure or there is a non-anesthesiologist with training to provide deep sedation or general anesthesia in your practice.8,9

Paracervical Block

Paracervical block has been described in the literature since the beginning of the last century.10 It was used to provide pain control in early labor11 and is actually the procedure of choice for gynecologic office procedures.12 Innervation of the uterus and cervix arise from the S2-S4 roots and nerves travel to the uterus in the lower portion of the broad ligament to the paracervical ganglion. Anesthesia of this plexus is the basis of the paracervical block.11,13 Paracervical block is used for LEEPs, diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy (tubal occlusion and global endometrial ablation), pregnancy terminations, some difficult endometrial ablations, IUD insertions, and cervical biopsies.12, 13, 14

Contraindications are allergy to anesthetic agent and local infection. The technique of paracervical block itself is not standardized. Several studies have demonstrated that paracervical block diminished pain perception in patients going under in-office gynecologic procedures. There are multiple reports describing where the local anesthetic should be injected, for example, at 4 and 8 o’clock,15 3 and 9 o’clock, 3-5-7-9 o’clock,16 and injecting the anesthetic at the cervicovaginal junction or in the cervical stroma.13 Beneficial techniques include use of carbonated lidocaine, deep injection to 3 cm, a foursite injection, slow injection (over 60 seconds), and waiting 3 to 5 minutes before the schedule procedure.14,17,18

22-gauge, 1.5-in needle × 1 (to inject), 18-gauge needle × 2 (to draw)

Needle extender × 1

10 mL syringe × 1, 20 mL control syringe (Luer lock type) × 1

Single-tooth tenaculum

Lidocaine (1%) 20 mL

Ropivacaine (0.2%) 30 mL

2 mL 8.4% sodium bicarbonate

Sterile Q tip (6, large)

Sterile cup (to mix anesthetics)

Antiseptic (povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine)

Speculum

Procedure

Mix 30 mL ropivacaine, 10 mL lidocaine, and 10 mL normal saline in a sterile cup and 2 mL 8.4% sodium bicarbonate.

Use 20 mL control syringe and an 180-gauge needle to draw the anesthetics; change to 22-gauge, 1.5-in needle on a needle extender.

Insert the speculum, examine the cervix, and use a large Q-tip and antiseptic to clean the cervix and the fornices.

Inject 1 mL of the preparation or 1% lidocaine at 12 o’clock position of the cervix, at the tenaculum site.

Apply single-tooth tenaculum.

Inject 7.5 to 10 mL of the preparation at 3-5-7-9 o’clock or 4 and 8 o’clock.

Wait 3 to 5 minutes for the preparation to work.

Complications

Local anesthetic toxicity and intravascular injection that can produce convulsions, cardiac arrhythmias, and respiratory arrest. After the injection, ask patient about metallic taste because it is an early sign of systemic toxicity.19

Vasovagal reaction with rapid onset of bradycardia, hypotension, pallor, and faintness

Anaphylaxis signs are hypotension, bronchospasm, urticaria, and edema.20

All complications can be fatal and the provider needs to have advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) training and all the necessary equipment to manage the complications and a plan in place to transfer patients to a nearby hospital.

BARTHOLIN DUCT CYST AND ABSCESS

Bartholin gland cysts and abscesses account for 2% of gynecologic visits per year21 and result from an obstruction of the Bartholin duct, which is followed by the accumulation of mucus within the duct. This fluid may become infected and become purulent, therefore constituting an abscess. The Bartholin cysts are commonly asymptomatic, but patients with larger cyst may complain of discomfort during intercourse or pain while sitting or walking. Patients with Bartholin abscesses, however, tend to complain of pain and a rapidly enlarging unilateral vulvar mass,22 and on exam, erythema of the skin overlying the abscess may be present, as well as fever, tachycardia, cellulitis, and an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count. These abscesses are usually fluctuant masses located on the right or left of the introitus, external to the hymenal ring and at the lower aspect of the vulva near the posterior fourchette (at 5 and 7 o’clock). Once drained, the purulent fluid from the abscess may be sent for culture and usually reveals a polymicrobial infection. The bacteria commonly found are Bacteroides species, Peptostreptococcus species, Escherichia coli, and Neisseria gonorrhea.23 Incision and drainage (I&D) alone may give immediate relief but probably temporary. Unless a new tract is created, the incision edges may seal and cause a re-accumulation of mucus or pus.

Permanent resolution usually occurs following an I&D with Word catheter placement and marsupialization, which are the two main outpatient managements

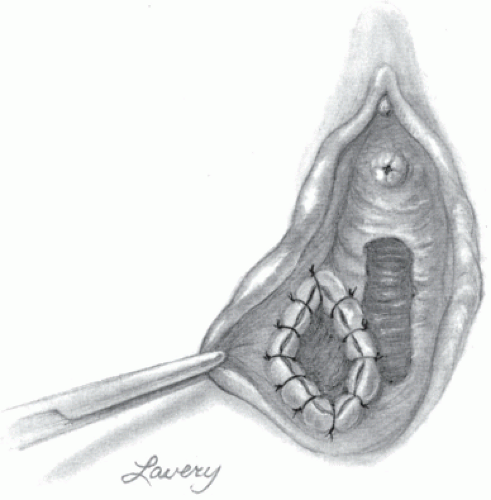

used and discussed in this chapter. Silver nitrate gland ablation and carbon dioxide laser treatments have also been used. The silver nitrate treatment has only been documented in Turkey and has been associated with vulvar mucosal cauterization,22 but when compared to marsupialization revealed complete healing with less scar formation.24 Both silver nitrate ablation and carbon dioxide laser treatments need further data before they can be accepted as standard treatment methods25 (Figs. 28.1 and 28.2).

used and discussed in this chapter. Silver nitrate gland ablation and carbon dioxide laser treatments have also been used. The silver nitrate treatment has only been documented in Turkey and has been associated with vulvar mucosal cauterization,22 but when compared to marsupialization revealed complete healing with less scar formation.24 Both silver nitrate ablation and carbon dioxide laser treatments need further data before they can be accepted as standard treatment methods25 (Figs. 28.1 and 28.2).

Incision and Drainage With Word Catheter Placement

Indication

Small asymptomatic cysts should be left alone. In symptomatic Bartholin cyst or any Bartholin abscess, an I&D followed by Word catheter placement is an option for management and provides in most cases immediate relief to the patient. The Word catheter is made of latex with an inflatable balloon at one end and an injection hub at the other end. The principle behind this procedure is to create a fistula by placing the catheter into the cyst to form a permanent epithelialized tract.21 The procedure can be performed under local anesthesia. The Word catheter has its limitations however, such as difficulty of maintaining the catheter in the correct place for the appropriate interval time of 4 to 6 weeks.

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to performing an I&D and Word catheter placement.

Equipment

1% lidocaine with syringe to inject it

Scalpel (no. 11 blade) and handle

FIGURE 28.1 Vulvar disease, Bartholin gland cyst. (Courtesy of LifeART image copyright © 2014 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights reserved.)

FIGURE 28.2 Bartholin gland cyst. (Image from Rubin E, Farber JL. Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999.)

Betadine (or another antiseptic solution)

Hemostat

Culture swab

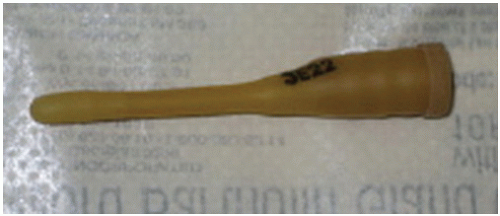

Word catheter (Fig. 28.3)

Syringe with 2 to 3 mL of sterile saline

Procedure

Place the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position.

Cleanse the area of the Bartholin cyst/abscess with a suitable antiseptic solution.

Inject 1% lidocaine at the expected incision site.

With the scalpel, make a 1 cm incision, which should be on the medial side of the cyst, close and parallel to the hymenal ring. The thinnest area is desired.

Send culture of the drained fluid.

A hemostat may be used to break any loculations.

Biopsy of the cyst wall may be indicated in women older than 40 years of age.

Diluted Betadine placed into a syringe can be used to irrigate the cyst cavity.

A Word catheter is then placed into the cyst cavity to keep the drainage tract open. The tip of the deflated Word catheter is placed into the cyst cavity and the balloon is then inflated by injecting 2 to 3 mL of sterile saline into the port of the catheter.

Finally, tuck the hub of the catheter into the vagina to prevent dislodgement.

Aftercare

If the procedure was performed for an abscess, significant cellulitis may be present, warranting an antibiotic regimen. The antibiotic should be broad spectrum to cover polymicrobial infections (anaerobes and aerobes).21 Patients should be instructed to perform sitz baths twice daily. Ideally, the catheter is to remain in place for 4 to 6 weeks, although it often falls before this time. There is no need to try to replace the catheter if dislodged early; it is usually impossible to do due to a decrease in cavity size. If the catheter remains in place for 3 to 4 weeks, the tract becomes epithelialized and the catheter can be removed.

Complications

Patients should be counseled about the risks of bleeding, pain, and repeat infection. A recurrence of the Bartholin cyst or abscess is common following an I&D alone or with early dislodgement of the Word catheter. The recurrence rate is 2 to 17%. Patients should be aware of the possible need for a repeat I&D or a marsupialization.

Marsupialization

Indications

Recurrences of Bartholin cysts or abscesses are common after a simple I&D. In these cases, a marsupialization is an option. Since the use of the Word catheter, however, the marsupialization procedure has had limited use. Their recurrence rates are similar and the marsupialization procedure requires a larger incision, placement of sutures, and longer procedure time compared to the I&D and Word catheter placement.24 The procedure entails creating a new duct to prevent a re-accumulation of mucus or pus.

Recurrence rates after a marsupialization is low and it makes it possible to avoid excising the gland with the cyst, allowing preservation of the secretory function of the gland for lubrication. The excision of the gland, a bartholinectomy, has been associated with many complications, including failure to remove the entire cyst, intraoperative or postoperative hemorrhage or hematoma, and occasionally, formation of scarring tissue. The marsupialization can be performed in the office (under local anesthesia or a pudendal block) or in the operating room (under general or regional anesthesia).

Contraindications

Marsupialization of a Bartholin abscess is contraindicated. In general, definitive surgical management is best deferred until a period of quiescence.

Equipment

1% lidocaine with syringe to inject it

Scalpel

Alice clamps

Hemostat

Delayed absorbable suture

Needle holder

Suture scissors

Procedure

The patient should be placed in the dorsal lithotomy position and the vagina and the vulva should be sterilely prepped.

A 2- to 3-cm skin incision parallel to the hymenal ring is performed using the scalpel. Care should be taken to only incise the skin and not puncture the cyst wall. The fluid-filled cyst should be visualized at this time.

The cyst wall is then incised with the scalpel, and the incision is extended superiorly and inferiorly. Allis clamps are then placed at the superior, inferior, right, and left edges of the cyst.

Using the tip of a hemostat, break any loculations that may be present in the cyst cavity.

Biopsy of the cyst wall may be indicated in women older than 40 years of age.

The cavity should be rinsed with normal saline.

The edges of the cyst wall are then sutured to the vestibule with interrupted sutures using 2-0 or 3-0 delayed absorbable suture.

Aftercare

Warm sitz baths once or twice daily are recommended to aid in pain relief and wound cleansing. Patients should be seen within a week after the procedure to confirm that the new duct is still patent. Within 2 to 3 weeks, the ostium shrinks to a 5 mm or less opening.

Complications

Recurrences after marsupialization are rare. However, if a recurrence occurs, a marsupialization may be repeated or a bartholinectomy may be warranted.

INTRAUTERINE DEVICE PLACEMENT AND REMOVAL

There was a time when approximately 7% of sexually active women in the United States used an intrauterine device (IUD) for contraception. However, the popularity

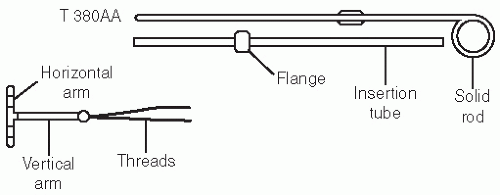

of the IUDs has fallen. In 1995, the National Survey of Family Growth reported that fewer than 1% of women who use contraception use an IUD.28 The IUDs are more common in China where 40% of women use them for contraception.28 The two devices approved for use in the United States are the Mirena (levonorgestrel-containing device) and the Paraguard T 380A (copper-containing). The respective failure rates for these devices are 0.1 and 0.8%, respectively.29 The Mirena releases levonorgestrel at a constant rate of 20 mcg/day. The Paraguard is wound with fine copper wire for a total of 380 mm2 of copper.30

of the IUDs has fallen. In 1995, the National Survey of Family Growth reported that fewer than 1% of women who use contraception use an IUD.28 The IUDs are more common in China where 40% of women use them for contraception.28 The two devices approved for use in the United States are the Mirena (levonorgestrel-containing device) and the Paraguard T 380A (copper-containing). The respective failure rates for these devices are 0.1 and 0.8%, respectively.29 The Mirena releases levonorgestrel at a constant rate of 20 mcg/day. The Paraguard is wound with fine copper wire for a total of 380 mm2 of copper.30

Indications

IUDs are effective reversible contraceptive methods, made of nonabsorbable material (most often polyethylene), that do not have to be replaced for 5 (Mirena) and 10 years (copper T). The Mirena can also be used as management for menorrhagia by reducing menstrual blood flow, which in turn is often associated with reduction in dysmenorrhea.31,32 Even though there is a higher up-front cost, their long-term cost effectiveness is competitive with other forms of contraception.30

Contraindications

General contraindications to IUD placement are pregnancy, uterine abnormalities causing distortion of the endometrial cavity, acute cervicitis or pelvic inflammatory disease, postpartum endometritis or infected abortion in the past 3 months, abnormal uterine bleeding of unknown etiology, women with multiple sexual partners, and a history of a prior ectopic pregnancy.28,30

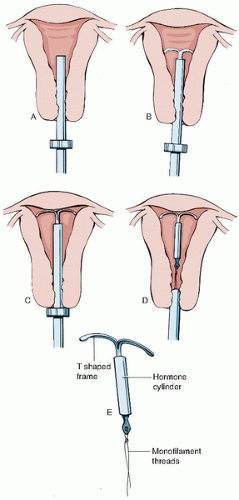

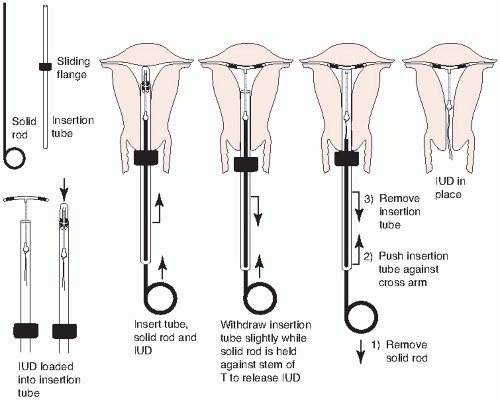

FIGURE 28.4 ParaGard insertion. (From Beckmann CRB, Frank W, Smith RP, et al. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.) |

The Paraguard is also contraindicated in patients with a copper allergy or history of Wilson disease. The Mirena is contraindicated in women with known or suspected carcinoma of the breast, hypersensitivity to any component of the device, or with acute liver disease or tumor.33

Equipment

Practitioners should have this list of equipment for placement of an IUD:

Sterile gloves

Speculum

Betadine solution (or another antiseptic solution)

Single-tooth tenaculum

Uterine sound

IUD package

Scissors

Procedure

Once the practitioner rules out any contraindications to placement, the patient should be counseled about all the risks and benefits associated with the device. Patient should sign an informed consent before the procedure.

Paraguard Placement (Figs. 28.4 and 28.5)

Place the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position.

Perform a bimanual exam to note the size and position of the uterus and assess for any adnexal masses.

If any abnormalities are found, they should be evaluated prior to placement of the device.

Place a speculum in the vagina, allowing visualization of the cervix.

Cleanse the cervix with an antiseptic solution, such as Betadine.

Using sterile technique, place the single-tooth tenaculum at the anterior lip of the cervix.

Sound the uterus and then place the blue plastic flange on the outside of the inserter tube at the sounded distance from the tip of the device.

Load the device into the inserted tube and tuck the arms into the tip of the inserter.

While stabilizing the cervix and straightening the cervical canal with the tenaculum, the inserter tube, with the device loaded, is then passed through the external os into the endometrial cavity until the blue flange abuts the cervix.

Hold the solid white rod in the tube steady, and then withdraw the inserter tube no more than 1 cm to allow release of the arms into the cavity.

Move the insertion tube upward toward the fundus until resistance is felt to ensure placement of the device at the highest position in the uterus.

Withdraw the solid white rod and the insertion tube. Only the strings should be visible protruding through the cervix.

Cut the strings so that 2 to 3 cm of thread protrude into the vagina.

Remove the tenaculum and assure hemostasis at the tenaculum puncture sites. Hold pressure if needed.

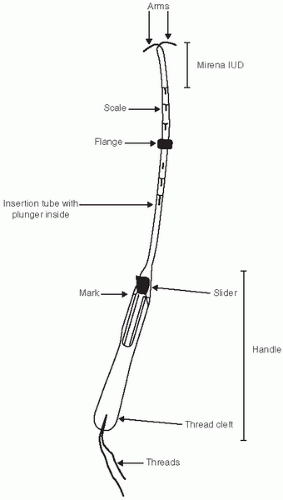

Mirena Placement (Figs. 28.6 and 28.7)

The Mirena placement is slightly different from the Paraguard.

Pick up the Mirena from the package and release the strings from behind the slider.

The slider should be positioned at the top of the handle, end closest to the device.

Align the arms of the device horizontally and pull on the threads to draw the device into the insertion tube.

Set the flange at the distance measured by the sound.

With the tenaculum placed at the anterior lip of the cervix, apply some traction on the cervix and insert the tube into the endometrial cavity until the flange is ˜1.5 cm away from the external os.

While holding the insertion tube steady, release the arms by pulling the slider back until the top of the slider reaches the raised horizontal mark on the handle.

Push the inserter forward until the flange touches the cervix, which should bring the device to the fundus.

Release the device by pulling the slider down all the way. This will release the threads.

Remove the inserter from the uterus and cut the threads so that they protrude 2 to 3 cm for the external os.

Aftercare

Patients should be allowed to feel the consistency of the threads after placement of the device and counseled to check for the strings every month after their menses to

confirm the device is still in place. Patients should also return to their practitioner to confirm visualization of the strings 1 month after placement.

confirm the device is still in place. Patients should also return to their practitioner to confirm visualization of the strings 1 month after placement.

Complications

Numerous complications from these devices have been described. However, they are usually not serious and the serious complications are not common.28,30,34

Expulsion

The expulsion of the device is most common in the first month after placement. Patients should be taught how to palpate for the strings. Patient should be examined 1 month after placement to confirm appropriate placement by visualizing the strings.

Uterine Perforation

A uterine perforation may be silent or clinically apparent. It is a complication that can occur early in the placement of the devices, while sounding the uterus or during insertion. Its occurrence rate is approximately 1 per 1000 insertions.35 The devices may also migrate through the uterine wall and can be partially or completely in the abdominal cavity.35

Loss of Device

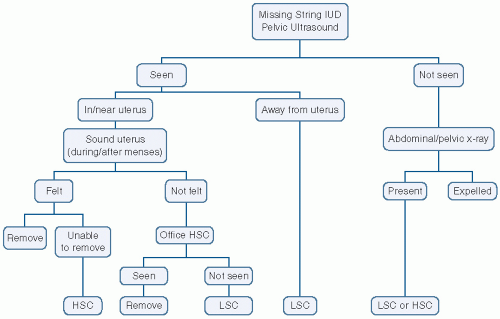

When the strings of the device cannot be visualized protruding through the external os, the device may have been expelled or may have migrated in the uterus or perforated the uterus into the peritoneal cavity. Gentle probing with a hook may be performed because in some instances the strings could be in the cervical canal in a well-positioned IUD. If the device is not felt with gentle probing, sonography to evaluate the uterine cavity should be performed.36 If the device is in the uterus and removal is needed or desired, it can be performed hysteroscopically. If the device is not visualized in the uterine cavity, a plain x-ray of the abdomen and pelvis is warranted.36 Laparoscopic removal of the device can be performed once identified in the abdominal cavity37 (Fig. 28.8).

Cramping and Bleeding

Patients should be counseled that uterine cramps and bleeding soon after the insertion of the IUD is common and may persist for a variable time. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be administered to decrease the cramping. Irregular menses for a period of time can also be experienced, especially with the Mirena.

Menorrhagia

Infection

The major risk of infection is at the time of insertion and does not increase with long-term use.28,34 The main risk factors for an infection are sexual behavior and history

of sexually transmitted diseases. Therefore, appropriate counseling and patient selection are key. With suspected pelvic infection, however, there is mixed evidence of whether the IUD should be removed after therapy has been initiated.41

of sexually transmitted diseases. Therefore, appropriate counseling and patient selection are key. With suspected pelvic infection, however, there is mixed evidence of whether the IUD should be removed after therapy has been initiated.41

FIGURE 28.8 Algorithm for managing the “missing string” IUD. (From Baggish MS, Valle RF, Guedj H. Hysteroscopy: Visual Perspectives of Uterine Anatomy, Physiology and Pathology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|