Obstetric Hysterectomy

Obstetric hysterectomy refers to surgical removal of the pregnant or recently pregnant uterus. The term includes hysterectomy with the pregnancy in situ, as well as operations related to complications of delivery. This chapter focuses on peripartum hysterectomy including cesarean hysterectomy and postpartum hysterectomy. These procedures are indispensable for management of intractable obstetric hemorrhage unresponsive to other treatment. The procedure frequently is lifesaving and should be within the capabilities of all obstetric consultants. Peripartum hysterectomy can be a formidable operation, particularly when performed for a life-threatening emergency, and the skills necessary for its performance are best acquired with an experienced mentor during scheduled nonemergency cases.

HISTORY

Obstetric hysterectomy was developed in the late eighteenth century to make it possible for women to survive cesarean delivery. Cesarean deliveries were uniformly fatal until the late nineteenth century. Until that time, bleeding and infections were untreatable complications. There were no intravenous fluids, antimicrobial drugs, or blood transfusions. Anesthetics were limited or nonexistent, and surgical antisepsis was not widely practiced. Obstetricians lacked the knowledge and techniques to perform safe pelvic surgery.

Pelvic deformities from nutritional deficiencies or infectious diseases were common until the early twentieth century. Women with a deformed pelvis had no reliable contraception, and mothers with a very small or distorted pelvis often labored to exhaustion and died along with their babies. Some attendants used fetal destructive operations to attempt to save the mothers, who often had extensive pelvic soft tissue injuries if they survived.

Joseph Cavallini of Florence developed the concepts that enabled the development of obstetric hysterectomy in the late eighteenth century. In 1768, he used animal experiments to disprove the prevailing idea that the uterus was an essential organ for life, and he removed the uterus successfully in pregnant and nonpregnant animals (Durfee, 1969). Investigators in Germany and England in the early 1800s concluded that abdominal delivery in animals was less dangerous if they removed the uterus after delivery (Young, 1944). These experiments prepared the way for safe cesarean delivery, as well as for obstetric hysterectomy.

The earliest documented human peripartum hysterectomy was performed in 1868 by Horatio Robinson Storer of Boston (Bixby, 1869). Storer was America’s first specialist in diseases of women, and he was confronted by a woman whose labor was obstructed by a large uterine tumor. The baby was already dead, but the tumor prevented any fetal destructive procedures. Storer performed cesarean delivery and because of life-threatening hemorrhage, he removed the uterus with its “fibrocystic tumor the size of a baby’s head.” Ligatures around the cervix and the tumor pedicle controlled bleeding. The cervical stump was seared with a hot iron and returned to the pelvis, after which the abdominal wound was closed with silver wire. The patient recovered from the chloroform anesthetic but died 3 days later.

Eduardo Porro (1876) published the first case report to describe a patient who survived hysterectomy after cesarean delivery. For this reason, some clinicians still refer to cesarean hysterectomy as the “Porro operation.” Before this case, Porro had previously performed an emergency cesarean delivery in a woman with obstructed labor from a rachitic pelvis. She had died, as had almost every woman after abdominal delivery. Determined to prove the safety of cesarean delivery, Porro repeatedly rehearsed cesarean hysterectomy in the animal laboratory.

Isaac Taylor of New York performed the first Porro operation in the United States in 1880 (Durfee, 1969). The woman died of a pulmonary embolism 3 weeks after an otherwise successful operation. Soon after, E. Richardson reported the first maternal survival after a Porro operation in the United States. In 1880, Robert P. Harris reviewed the world literature on cesarean hysterectomy. He collected 50 cases from seven countries. The maternal mortality rate was 58 percent and the fetal survival rate was 86 percent. In 1884, Clement Godson of England reviewed a total of 134 cases. At that time, the most common indication for surgery still was a contracted pelvis due to rickets. He reported a maternal mortality rate of 45 percent with death usually due to peritonitis, shock, and septicemia.

European surgeons modified the Porro procedure in an attempt to reduce operative risks and to improve outcomes. Tait (1890) of England published changes that were widely adopted. The Tait-Porro operation enjoyed increasing popularity, and indications for the procedure expanded beyond absolute emergencies as surgical techniques improved.

The extensive experiences with cesarean hysterectomy at Charity Hospital in New Orleans began in 1938 and were reported by Barclay (1970) and Mickal and associates (1969). The ongoing Charity Hospital experiences have since been reported periodically with steadily improving outcomes (Bey and coworkers, 1992; Gonsoulin and associates, 1991; Plauché and colleagues, 1981, 1983).

The majority of obstetricians reserved peripartum hysterectomy for life-threatening emergencies. Davis (1951) of Chicago, however, championed elective cesarean hysterectomy and cited a 20 percent incidence of hysterectomy in a series of 736 cesarean deliveries. Brenner and colleagues (1970) concluded that complications outweighed benefits if hysterectomy was performed for sterilization and that tubal ligation after either cesarean or vaginal delivery was safer.

Currently, enthusiasm for nonemergency peripartum hysterectomy varies by region across the United States. Some programs teach obstetric hysterectomy when indications for cesarean delivery coexist with gynecologic indications for hysterectomy. Most reserve peripartum hysterectomy for major obstetric emergencies.

CLASSIFICATION

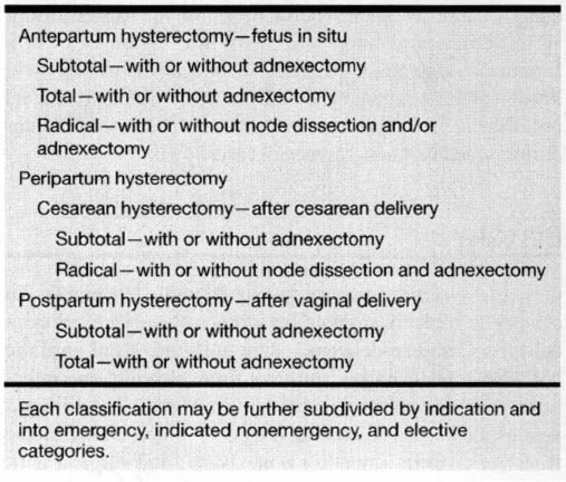

Shown in Table 16-1 is a classification for obstetric hysterectomy. Careful classification considers the timing, indication, extent, and circumstances associated with each case. Peripartum hysterectomies include those following cesarean delivery (cesarean hysterectomy) and those following vaginal delivery (postpartum hysterectomy). Either operation may be subtotal, total, or radical, with or without removal of one or both adnexa. Each operation may be identified as an emergency, an indicated nonemergency, or an elective case. Only when all these factors are considered can valid conclusions be drawn about comparative risks and outcomes.

TABLE 16-1. Classification of Obstetric Hysterectomy

INDICATIONS FOR OBSTETRIC HYSTERECTOMY

EMERGENCY INDICATIONS

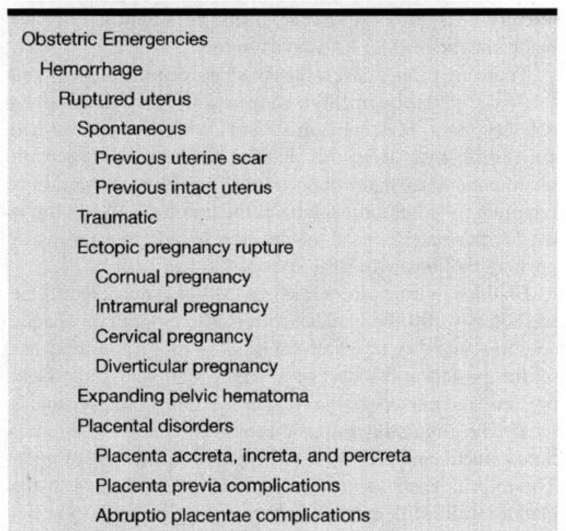

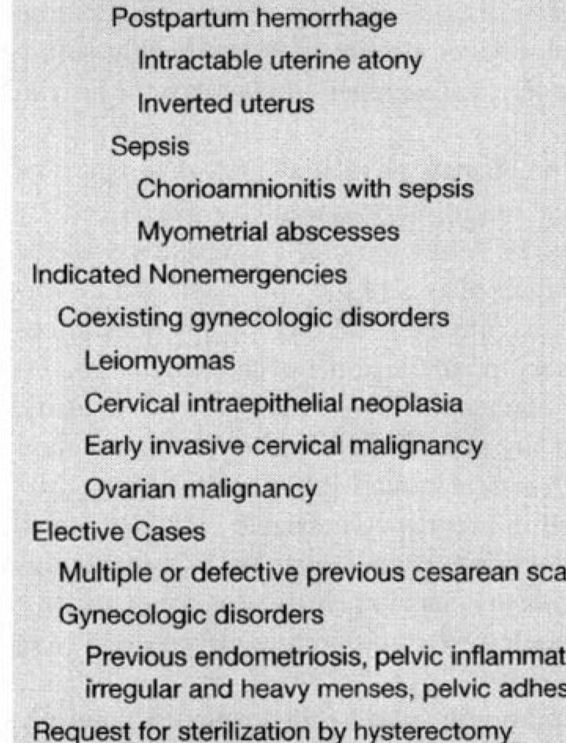

Listed in Table 16-2 are many of the published indications for obstetric hysterectomy. Emergency indications are less common than in the past, as there are now less-invasive alternative treatments available.

TABLE 16-2. Indications for Obstetric Hysterectomy

Contemporaneously, hysterectomies are performed as final efforts to stop intractable hemorrhage. In 1964, Bowman and colleagues reported that 55 percent of cesarean hysterectomies at Charity Hospital were done for postpartum hemorrhage and two-thirds of these were for uterine atony. While less-invasive methods control most cases of uterine atony, some unresponsive cases still require hysterectomy as a lifesaving measure. More recently, uterine atony was the indication for 20 percent of emergency peripartum hysterectomies reported by Stanco and colleagues (1993) from Los Angeles County Hospital, and by Zelop and associates (1993) from Harvard.

Ruptured uterus is the second most common indication for emergency hysterectomy for hemorrhage. In the Los Angeles report cited above, all uterine ruptures that required emergency hysterectomy were in women with previous cesarean delivery scars. Similarly, 60 percent of emergency hysterectomies in the Harvard series were done in women who previously had cesarean deliveries. A previous cesarean section increases the likelihood of placenta previa, placenta accreta, scar dehiscence, and overt uterine rupture, and each of these diagnoses increases the risk for emergency hysterectomy (Leung and colleagues, 1993; Zelop and coworkers, 1993).

There has been great interest in the risk of uterine rupture during trials of vaginal birth after cesarean section. Uterine rupture required hysterectomy in 1 of 555 trials of labor cited in the review by Stanco and colleagues (1993). Leung and coworkers (1993) reported scar rupture requiring laparotomy in 70 of 8513 cases (1 in 122). In earlier years, uterine scar dehiscence discovered at repeat cesarean section was a common indication for hysterectomy. For example, almost half of the Charity Hospital cases in the first three decades were performed for a defective scar. Contemporary management is now quite different, as experience has accrued that scars that appear thin and minor dehiscences may be safely repaired rather than performing hysterectomy.

Major scar dehiscences and overt ruptures can be managed either by repair or by hysterectomy. Catastrophic uterine ruptures, particularly of the unscarred uterus, most often require hysterectomy; however, there is a recent trend for repair in selected cases (Plauché, 1991). The decision of uterine repair versus removal depends on the extent of damage, the hemodynamic stability of the woman, and the desire for future pregnancies. The operating environment and experience and training of the surgeon also play important roles in the decision.

Placental disorders are the third most frequent cause of emergency obstetric hysterectomy for bleeding. Most of these are from placenta accreta with or without an associated previa. Accreta has increased in frequency as an emergent indication for hysterectomy, and 65 percent of emergency procedures in the Harvard series were performed for this reason.

Severe uterine infections that formerly required cesarean hysterectomy usually respond to modern antimicrobial therapy. Sepsis from chorioamnionitis is rare because of aggressive management of prematurely ruptured membranes. Tinga (1986) reported several women with neglected infections that developed myometrial abscesses or intractable uterine atony that required hysterectomy and pelvic drainage.

NONEMERGENCY INDICATIONS

Peripartum hysterectomy is more controversial when performed for reasons other than obstetric emergencies. These indicated but nonemergent procedures are performed when women requiring cesarean delivery also have a gynecologic disorder that is usually managed by hysterectomy. These have been variously termed nonemergency, planned, or anticipated cesarean hysterectomies (Plauché, 1991; Zelop and colleagues, 1993). The rationale is to perform both cesarean delivery and hysterectomy with a single procedure and anesthetic.

Uterine leiomyomas and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia are common indications (Plauché, 1991). McNulty (1984) reviewed a 10-year experience with 80 planned cesarean hysterectomies performed in several California private hospitals. The most prevalent diagnoses in this series were uterine leiomyomas (25 percent) and defective scars after previous cesarean operations (28 percent). Another 25 percent had other benign gynecologic conditions and 5 percent had a pelvic malignancy. These are similar to the 5-year British experience reported by Sturdee and Rushton (1986). Conversely, Yancey and associates (1993) reported that abnormal gynecologic bleeding (34 percent) or chronic pelvic pain (32 percent) constituted the most common indicators.

ELECTIVE

Completely elective obstetric hysterectomies are not endorsed by most investigators (McNulty, 1984; Mickal and colleagues, 1969; Plauché, 1986). Although in earlier series, sterilization was the ostensible indication for cesarean hysterectomy, none of these authors encouraged primary abdominal delivery to create opportunities for surgical sterilization by hysterectomy.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

There are a number of anatomic and physiologic changes in pregnant women that increase the likelihood of intraoperative problems. The uterus is markedly enlarged and pelvic blood vessels are large and tortuous. Collateral vessels are also enlarged. Moreover, pelvic tissues are edematous and more friable than in nonpregnant women. Rapid control of all vascular supply to the uterus is essential. Dilated vessels and multiple collaterals require careful dissection. Extra clamps are necessary to avoid retrograde blood loss from severed blood vessels. The distal two-thirds of clamps hold tissues and vessels with maximum security. Clamps on vascular pedicles should be manipulated as little as possible. All pedicles should be inspected several times for hemostasis before completing the case.

The bulky uterus is difficult to manipulate during obstetric surgery. It cannot be safely manipulated by means of clamps on friable adnexal structures. A tumor tenaculum placed on the uterine fundus is an efficient traction device. A finger in the apex of a vertical cesarean incision also provides effective traction and manipulation.

The bladder wall becomes edematous and friable during labor and may be injured by blunt dissection. Rotating retractors held under tension can also injure the bladder. Assistants should release traction before repositioning bladder retractors. A laparotomy sponge placed between the retractor blade and the bladder helps avoid injury.

There are often dense adhesions between the bladder and the lower uterine segment in women with previous cesarean delivery scars. Metzenbaum scissors with the curve turned downward, away from the bladder, can be used to accomplish meticulous sharp dissection. When blunt dissection is required, rolled umbilical tape in the tip of a Kelly clamp is used with small, focused movements. Avoid gross rolling or pushing motions with large sponges.

Bladder injuries are sometimes difficult to detect. One method is to fill the bladder with sterile colored or opaque solutions and then to search for small or hidden perforations of the posterior bladder wall. Many find that milk from presterilized nursery bottles and drawn into a bulb syringe is ideal. The circulating nurse attaches the syringe to the urethral catheter and fills the bladder with 200–300 mL of milk. The milk is easily seen flowing from small defects in the bladder wall. Milk can be used repeatedly during a case because it does not stain tissues. Bladder defects are repaired promptly using a two-layer closure with absorbable suture (see Chap. 25). Undetected, unrepaired bladder injuries can result in fistulas.

The ureter in pregnancy is dilated and sluggish. The ureter and bladder might be damaged or displaced by trauma, hematomas, or pelvic tumors. The proximity of the ureter is observed at all phases of the operation, and dissection of its course is recommended if there is any question of its safety. If necessary, open the dome of the bladder and insert retrograde ureteral catheters to ensure ureteral integrity. Repair and support any identified ureteral injury by standard methods along with expert intraoperative consultation.

The vaginal wall in pregnancy is friable and edematous, particularly in the laboring woman. Firm traction on clamps attached to the vagina may lacerate the tissues. Postoperative bleeding can be avoided by incorporating all vaginal layers in the cuff closure.

Sutures may cut through friable pedicles unless carefully secured. Pedicles shrink in size as edema subsides after delivery. Single circumferential sutures may allow vessels to escape control. Transfixing sutures improve hemostatic control when edema subsides. Hematomas can result if transfixing sutures are used alone without circumferential proximal ties.

Traction or twisting of clamps on vascular pedicles may strip pedicles away from adjacent tissues. This technique opens blood vessels that are difficult to clamp and suture without injury to nearby structures, particularly the ureter and bladder. Clamps should be supported, not manipulated, during suturing.

Meticulous hemostatic and aseptic technique reduce infectious complications. Careful hemostasis at the vaginal cuff prevents postoperative bleeding and cuff hematomas. Infected cuff hematomas may suppurate to form cuff abscesses. Prophylactic antimicrobials are recommended for women who have been in labor (see Chap. 35). In grossly infected cases, the skin and subcutaneous tissues may be left open under surgical dressings. Delayed closure after antimicrobial treatment reduces the risk of wound suppuration and dehiscence.

THE ORIGINAL PORRO HYSTERECTOMY

Porro’s original technique is described for its historical interest and for contrast with current methods. Porro carefully followed nineteenth-century surgical techniques. The amphitheater was heated to a precise 18°C. The surgeons washed their hands with dilute carbolic acid. Chloroform anesthesia was induced, and a 12-cm vertical midline infraumbilical incision was made. A vertical uterine incision allowed delivery of a 3300 g female by version and extraction. Attempts at manual and suture control of bleeding after removal of the placenta were unsuccessful. He wrote: “It was providential that we had made all the preparations necessary for hysterectomy; otherwise the patient would surely have died.” An assistant elevated the uterus out of the abdominal wound. Porro slipped the wire noose of a Cintrat constrictor over the uterus and adnexa. The loop was tightened and the uterus and adnexa incised with a scalpel. He drained the culde-sac, treated the cervical stump with perchloride of iron, and exteriorized the Cintrat constrictor onto the abdominal wall. The abdominal wound was closed around these with silver wire mass sutures. The operation lasted 26 minutes.

The exteriorized constriction device was left on the cervical stump under dressings for 4 days. The wound sutures were removed on postoperative day 7. The ischemic cervical pedicle detached 7 days later. The woman left the hospital at 6 weeks.

CONTEMPORARY TOURNIQUET METHOD

Some surgeons still use a tourniquet around the lower uterine segment for hemostasis, as did Porro and his successors. The following method for peripartum hysterectomy is attributed to Leon Gaillard of Louisiana State University School of Medicine: Cesarean delivery is performed as usual. The assistant elevates the uterus out of the abdominal cavity. The operator transilluminates the broad ligaments to identify avascular spaces. Kelly clamps are placed through these windows on each side below the level of the uterine incision. A tourniquet is passed through the two openings in the broad ligament to encircle the uterus below the hysterotomy incision. The tourniquet can be a rubber catheter, heavy Penrose drain, or plastic intravenous tubing. The tourniquet is drawn very tight and secured by an Ochsner (Kocher) clamp at the back of the uterus. Hysterectomy then proceeds using the chosen technique.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree