KEY POINTS

• The physiologic changes of pregnancy are a significant factor in the anesthetic care of women during childbirth and sometimes increase the risks of anesthesia.

• Neuraxial anesthesia procedures, including epidural and combined spinal–epidural (CSE) analgesia, provide excellent pain relief during labor and are used in the majority of childbirths in the United States.

• Both neuraxial and general anesthesia techniques provide effective anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Historically, anesthesia-related maternal mortality has been greater when general anesthesia is used, but the difference in mortality rate between general and regional anesthesia has narrowed in the United States.

• Ensuring maternal safety and maintaining adequate uteroplacental perfusion and fetal oxygenation are the most important goals when anesthesia is administered for nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy.

BACKGROUND

Obstetric anesthesia is an important component in the care of most women during childbirth. Many women choose to receive neuraxial analgesia while in labor, and all women who undergo cesarean delivery require some type of anesthesia. Anesthesia care is also provided to the many women who require other surgical procedures while pregnant.

Pathophysiology

• The physiologic changes of pregnancy have a significant impact on the administration of both regional and general anesthesia to women during childbirth.

• Sensitivity of nerves to local anesthetics is enhanced during pregnancy (1).

• As a result, the local anesthetic dose requirements for both spinal anesthesia during surgery and epidural labor analgesia are decreased in pregnant women (2,3).

• The sedative effects of increased progesterone levels and the activation of the endorphin system during pregnancy also decrease general anesthesia requirements.

• The minimum alveolar concentration of halogenated volatile anesthetic agents, which is defined as the drug concentration at which 50% of patients do not move when exposed to a noxious stimulus, is decreased by approximately 30% in women during pregnancy (4).

• The dose of intravenous propofol needed to induce general anesthesia is also decreased in pregnant women (5).

• The physiologic changes of pregnancy may affect the safety of administering anesthesia to pregnant women.

• Aortocaval compression from the gravid uterus decreases venous return and can result in significant hypotension when a pregnant woman assumes the supine position, especially during late pregnancy.

• The sympathetic block produced by spinal and epidural anesthesia causes vasodilatation that results in a further decrease in venous return.

• The sympathectomy induced by neuraxial anesthesia impairs a pregnant woman’s ability to compensate via vasoconstriction for the decreased venous return caused by aortocaval compression. As a result, the degree of hypotension that occurs during neuraxial anesthesia is significantly greater in pregnant compared to nonpregnant women.

• Anesthesia-related maternal mortality is more common during general anesthesia than regional anesthesia although the difference in mortality rate between the anesthetic techniques has declined since 1990.

• A study of anesthesia-related maternal mortality in the United States between 1991 and 2002 found that the overall rate was 1.2 per million live births, which was a 59% decrease from 1979 to 1990; and 86% of those deaths occurred during cesarean delivery.

• The anesthesia-related case fatality rate for cesarean delivery under general anesthesia was 16.8 per million anesthetics from 1991 to 1996 with a decrease to 6.5 per million anesthetics for 1997–2002.

• The anesthesia-related case fatality rate for cesarean delivery under regional anesthesia was 2.5 per million regional anesthetics for 1991–1996 and 3.8 per million anesthetics for 1997–2002.

• Therefore, the risk of anesthesia-related mortality was 6.7 times greater for pregnant women receiving general anesthesia compared to regional anesthesia for 1991–1996, but the risk ratio had decreased to 1.7 for the period 1997–2002 (6).

• The majority of deaths during general anesthesia resulted from airway management problems, such as failed intubation and aspiration, while high neuraxial block was the most common cause of regional anesthesia-related deaths (6).

• The physiologic changes of pregnancy play a significant role in the increased risk of general anesthesia for pregnant women.

• Airway edema caused by pregnancy-induced capillary engorgement of the mucosa can distort airway anatomy and contributes to the increased incidence of difficult intubation in pregnant women.

• One study found that the incidence of difficult or failed intubation was approximately eight times greater in obstetric patients compared to nonpregnant patients (7).

• Respiratory changes of pregnancy, including decreased functional residual capacity and increased oxygen consumption, result in a more rapid development of hypoxemia when apnea occurs (8). Therefore, when difficult intubation is encountered during the induction of general anesthesia, an obstetric patient will become hypoxemic more quickly than a nonobstetric patient.

• A variety of physiologic factors contribute to the risk of aspiration in parturients.

• Gastric emptying is prolonged during labor (9,10). In addition, anatomic changes resulting from displacement of the stomach by the gravid uterus and decreased lower esophageal sphincter tone, caused by increased progesterone levels, produce an increased incidence of gastroesophageal reflux in pregnant women.

• Both delayed gastric emptying and gastroesophageal reflux are risk factors for gastric aspiration during the induction of general anesthesia.

• Aspiration is more likely to occur when difficult airway management is encountered and securing of the airway with tracheal intubation is delayed.

Epidemiology

• The majority of pregnant women in the United States will receive obstetric anesthesia.

• All patients undergoing cesarean delivery require anesthesia, and the cesarean delivery rate in the United States continues to rise; it had reached 32.8% of all deliveries in 2010 and 2011 (11).

• Approximately 75% of women who deliver at a hospital in the United States with greater than 1500 deliveries per year receive neuraxial analgesia during labor (12).

• Finally, based on estimates of the rate of surgery during pregnancy (0.3% to 2.2%), as many as 87,000 pregnant women in the United States undergo anesthesia for non–pregnancy-related surgical procedures each year (13).

EVALUATION

History

• Before providing obstetric anesthesia care, the anesthesiologist must perform a focused history and physical examination.

• Important components of the patient’s medical history include the presence of serious underlying medical conditions—especially cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurological disorders. The anesthesiologist must also be aware of any current pregnancy complications because the presence of these complications will affect decisions concerning anesthetic management.

• Crucial medical history information for the anesthesia care provider includes any available information concerning previous general or regional anesthetics. The anesthesiologist will seek any evidence of technical difficulties with regional or general anesthesia procedures, including a history of failed or difficult intubation.

• Adverse reactions to anesthetic drugs and a history of anesthesia-related inheritable disorders in the patient or her relatives, such as malignant hyperthermia and atypical pseudocholinesterase, should be noted.

Physical Examination

• The anesthesiologist’s focused physical examination of the obstetric patient will include auscultation of the heart and lungs and careful assessment of the airway.

• When a neuraxial anesthesia technique is planned, examination of the back is also essential.

• Most anesthesiologists would agree that the most important component of the physical examination in healthy pregnant women is airway assessment. Evaluation of the airway includes mouth opening, neck movement, thyromental distance, Mallampati classification, and the upper-lip bite test.

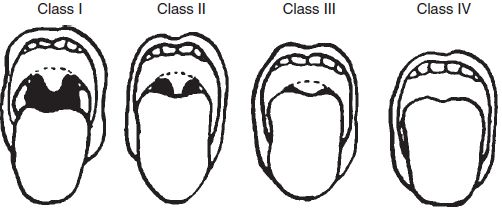

• The Mallampati airway classification system evaluates the size of the tongue relative to the size of the oropharyngeal cavity. Patients are assigned an airway class based on the pharyngeal structures that can be visualized when the patient opens her mouth wide and sticks out her tongue (Fig. 3-1). A correlation exists between Mallampati airway class and ease of intubation (14).

• Airway classification using the upper-lip bite test, which assesses a patient’s ability to cover the upper lip with the lower incisors, has also been shown to correlate with ease of intubation (15).

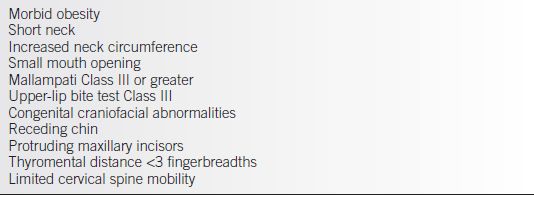

• Patient factors that increase the risk of difficult intubation are listed in Table 3-1.

• The anesthesiologist’s preanesthetic evaluation also involves an assessment of fetal status because fetal condition is an important factor when deciding upon an anesthetic plan of care.

Figure 3-1. Mallampati classification of the airway based on pharyngeal structures that are visible with mouth open. Class I: the soft palate, uvula, and tonsillar pillars are visualized. Class II: the uvula is only partially visualized, and the tonsillar pillars are not visualized. Class III: soft palate only is visualized. Class IV: not even the soft palate is visualized. (Reprinted from Chestnut DH. Obstetric anesthesia: principles and practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2004, with permission.)

Table 3-1 Risk Factors for Difficult Intubation

Laboratory Tests

• Healthy women who have received comprehensive prenatal care that included routine laboratory testing with normal results do not usually require additional laboratory tests before proceeding with regional or general anesthesia.

• If obstetric or other factors place the patient at increased risk for hemorrhage during delivery, a complete blood count and a blood type and screen or type and cross are indicated.

• Because the incidence of thrombocytopenia is increased in patients with preeclampsia, platelet count should be measured in these patients before performing regional anesthesia or surgery.

• If the platelet count is greater than 100,000/mm3, no other coagulation testing is required (16).

• If the patient does have a platelet count less than 100,000/mm3 or abnormal liver function tests, some anesthesiologists do request other coagulation studies, including prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, and activated partial thromboplastin time before initiating neuraxial anesthesia procedures.

There are data suggesting routine prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time testing is not necessary, even in the preeclamptic patient with thrombocytopenia (17).

There are data suggesting routine prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time testing is not necessary, even in the preeclamptic patient with thrombocytopenia (17).

When thrombocytopenia is present, some anesthesia care providers perform testing of platelet function, using either thromboelastography or PFA-100 analysis, before deciding whether to proceed with a regional anesthesia technique.

When thrombocytopenia is present, some anesthesia care providers perform testing of platelet function, using either thromboelastography or PFA-100 analysis, before deciding whether to proceed with a regional anesthesia technique.

• Although the lowest platelet count at which an anesthesiologist will perform a neuraxial technique varies widely among practitioners, an increasing number of anesthesiologists perform regional anesthesia for patients with platelet counts less than 100,000/mm3, especailly if the platelet count is at least 70,000/mm3.

LABOR ANALGESIA

Background

• Labor pain and approaches to its relief have been controversial for thousands of years. In the 15th century, midwives were burned at the stake for offering pain relief. Some advocates of psychoprophylaxis have suggested that labor pain is minor.

• In reality, the experience of labor pain varies widely among women.

• Although nearly a quarter of the women in one study reported their labor pain as minimal or mild, another 23% rated the pain as severe or intolerable (18).

• Using a questionnaire developed by one of the pioneers of modern pain research, labor pain was rated as more painful than cancer pain. Using this same questionnaire, nulliparous women who had not received prepared childbirth training rated their labor pain as nearly as painful as traumatic amputation of a digit (19).

• Since approximately 75% of women in labor in the United States receive neuraxial labor analgesia, one can safely assume that the majority of pregnant women do consider labor pain significant.

Pathophysiology

• To provide adequate labor analgesia, an understanding of the physiology and mechanisms of labor pain is necessary.

• First stage: The pain women experience during the first stage of labor is primarily visceral pain caused by cervical dilation. These visceral afferents travel via the T10-L1 nerve roots. Therefore, analgesia during the first stage of labor can be provided via blockade of these peripheral afferents using either epidural block of the T10-L1 dermatomes or paracervical block. Pain during the first stage of labor can also be relieved via blockade of pain transmission within the spinal cord using the subarachnoid injection of opioids and/or local anesthetics.

• Second stage: During the second stage of labor, patients continue to experience the visceral pain described above. In addition, they experience somatic pain that results from stretching of the vagina and perineum as the fetal head traverses through the birth canal. These somatic pain impulses travel via the pudendal nerve, which is composed of nerve fibers from the S2-S4 nerve roots. Blockade of these pain impulses can be achieved by extending epidural or subarachnoid block to include the S2-S4 dermatomes or by performing a pudendal nerve block.

TREATMENT

Medications

Opioids

• Although several studies have shown that neuraxial analgesia techniques provide superior pain relief and cause less neonatal depression than do systemic opioids, the use of parenteral medications to provide labor analgesia remains relatively common for several reasons.

• Some hospitals, especially those with few obstetric patients, do not have sufficient anesthesia care providers available to provide daily, 24-hour neuraxial labor analgesia services.

• Some patients have medical contraindications to regional anesthesia, and some patients refuse neuraxial procedures.

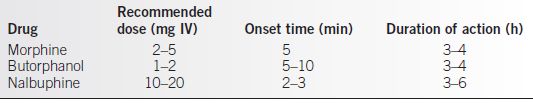

• Several different opioids can be used to provide labor analgesia. The obstetrician should be aware of the advantages and disadvantages, as well as the duration of action for each drug when deciding which systemic opioid to administer to a woman in labor.

• Table 3-2 describes the recommended dosing, onset time, and duration of action for commonly used systemic opioid medications.

• All systemic opioids rapidly cross the placenta and gain access to the fetus.

• Some adverse effects of systemic opioids are common to all of the medications, although to a greater or lesser extent depending on which drug was administered. These include decreased fetal heart rate variability and both maternal and neonatal respiratory depression.

• Meperidine has previously been one of the most widely used systemic opioids for labor analgesia in the United States and remains a commonly used systemic analgesic. There are significant disadvantages to this drug, however.

• Metabolism of meperidine and its active metabolite, normeperidine, is prolonged in newborns due to their immature livers. Compared to a maternal half-life of 2.5 to 3 hours, the half-life of meperidine in the newborn is 18 to 23 hours (20). The half-life of normeperidine in newborns is approximately 60 hours (21).

• These prolonged half-lives are responsible for the subtle neurobehavioral changes that have been reported in infants for as long as 5 days after maternal administration of meperidine (22).

• If meperidine is used for labor analgesia, attention should be paid to the anticipated time interval between drug administration and delivery. Maximal fetal uptake of the drug occurs 2 to 3 hours after administration, and increased risk of respiratory depression has been noted in infants who were born 2 to 3 hours after meperidine administration (23).

• Butorphanol and nalbuphine have become the systemic analgesics of choice in many labor and delivery suites.

• Butorphanol and nalbuphine are mixed agonist/antagonist opioids and provide analgesia similar to that provided by meperidine.

• One advantage of these drugs is that a ceiling effect on respiratory depression is reached as the dose of the drug is increased.

• Many women who receive these drugs during labor experience significant sedation.

• Agonist/antagonist opioids should not be administered to patients who are opioid dependent because they could precipitate withdrawal symptoms.

Table 3-2 Commonly Used Systemic Opioids for Labor Analgesia

Patient-Controlled Analgesia

• Although parenteral medications provide less effective labor analgesia than do neuraxial analgesia techniques, improved pain relief has been achieved with the administration of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV PCA) using potent, short-acting opioids such as fentanyl and remifentanil.

• In one study that used fentanyl IV PCA, 65% of women were satisfied with their labor analgesia and reported that they would use the technique again. Among these women, no maternal respiratory depression or significant sedation occurred. Although the authors reported no adverse neonatal outcomes, 16% of the newborns did receive naloxone (24).

• Remifentanil is an ultra-short-acting drug that would be expected to produce less neonatal depression than do other opioids. Its use for labor analgesia has increased significantly over the past few years. Because it is such a potent opioid requiring increased patient monitoring, most anesthesiologists prefer to offer this technique only to patients in whom neuraxial anesthesia is contraindicated. Some labor and delivery units have been successful in offering it as an analgesic option to all laboring women (25).

• In a recent study that compared IV PCA with remifentanil, fentanyl, or meperidine, women who received remifentanil reported lower pain scores and higher satisfaction with their labor analgesia (26).

• In the most recent study of remifentanil PCA in laboring parturients, 91% of women were satisfied with their pain management. Moderate maternal sedation occurred, and 27% of women did require supplemental oxygen for oxygen saturation less than 92%. No adverse neonatal effects were reported (27).

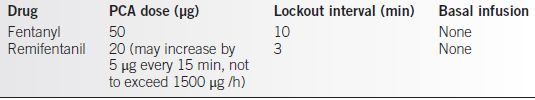

• Recommended dosing strategies for both fentanyl and remifentanil IV PCA are listed in Table 3-3.

• Because both of these drugs are significantly more potent than are other opioids commonly used for labor analgesia, caution is necessary when administering these medications in order to avoid serious respiratory depression.

• Administration of fentanyl and remifentanil should be supervised by health care providers experienced in the use of these drugs.

• Continuous pulse oximetry monitoring and close nursing surveillance are also needed.

Table 3-3 Recommended Dosing for Intravenous Patient-Controlled Labor Analgesia

PCA, patient-controlled analgesia.

Procedures

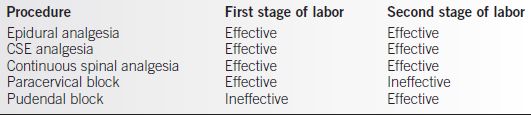

• Table 3-4 describes the techniques that are effective in providing pain relief during the first and second stages of labor.

• Epidural analgesia is the most common technique anesthesiologists use to provide labor analgesia. Every study that has compared epidural analgesia to systemic opioids for labor analgesia has found that epidural analgesia provides superior pain relief.

• CSE analgesia is another procedure commonly performed by anesthesia care providers to deliver excellent pain relief during labor.

• Continuous spinal analgesia is another acceptable procedure for providing labor analgesia in certain situations.

• Nerve blocks performed by the obstetrician can also be useful for achieving labor pain relief.

Table 3-4 Procedures for Providing Effective Labor Analgesia

Epidural Analgesia

• Epidural analgesia is the anesthetic procedure most commonly used in the United States to provide labor analgesia. In a recent national survey, hospitals that had more than 1500 births per year reported that 61% of their laboring patients received epidural analgesia (12).

• The advantages of epidural analgesia that make it so popular among anesthesiologists, patients, and obstetricians include an excellent quality of pain relief and versatility.

• With appropriate dosing, a segmental block from T10-L1 can be achieved early in labor with the block being extended over time to include the sacral nerve roots once the second stage of labor has been reached.

• By increasing the dose and concentration of drugs administered, epidural labor analgesia can be converted to a more dense, extensive block that provides anesthesia when a cesarean or operative vaginal delivery is necessary.

• A variety of dosing techniques have been used to provide effective pain relief during labor. The goal of the anesthesiologist when administering epidural labor analgesia is to provide effective analgesia while minimizing motor block, so the woman’s expulsive efforts during the second stage of labor are not adversely affected.

• One study found that the administration of higher concentrations of local anesthetic (bupivacaine 0.25%) for labor analgesia resulted in an increased incidence of operative vaginal deliveries (28). As a result, there has been a trend over the past 20 years to use lower concentrations of local anesthetics.

• Lipid-soluble opioids are commonly added to the local anesthetic solutions because they decrease local anesthetic requirements while achieving an equivalent quality of labor analgesia (29).

• Local anesthetics that produce relatively less motor block at equianalgesic doses, such as bupivacaine and ropivacaine, are also preferred for providing labor analgesia.

• A continuous infusion technique is commonly used (sometimes in conjunction with patient-controlled epidural analgesia [PCEA]) to provide labor analgesia. Recent data, however, suggest that programmed intermittent epidural boluses provide equivalent pain relief and higher patient satisfaction compared with a continuous infusion while using less local anesthetic (30). Epidural pumps that can be programmed to deliver automated boluses have recently become commercially available.

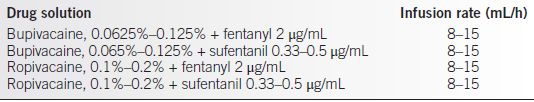

• Suggested dosing regimens for providing epidural labor analgesia with a continuous infusion technique are listed in Table 3-5. The degree of pain experienced by women in labor varies widely, and the dosing regimen used for individual patients should be titrated to meet their pain-relief requirements.

• The use of PCEA is an ideal technique for providing pain relief that can be individualized to meet each woman’s needs throughout labor. Many anesthesiologists prefer using PCEA rather than a continuous infusion.

• Several studies have compared PCEA with continuous infusion epidural analgesia during labor. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that women who received PCEA used less local anesthetic, developed less motor block, and required less interventions by anesthesia personnel. Despite using less local anesthetic, women who received PCEA achieved pain relief equivalent to that of women who received continuous infusions. Although some anesthesiologists have suggested that the patient’s ability to actively participate in her pain management will lead to increased satisfaction, a meta-analysis showed no difference in maternal satisfaction between women receiving PCEA or continuous infusion epidural analgesia. In addition, no differences in obstetric outcomes have been found between these two techniques of epidural analgesia, despite the use of less local anesthetic in women receiving PCEA (31).

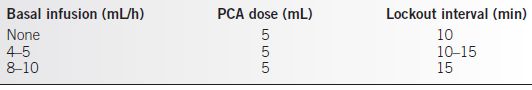

• A variety of dosing strategies have been suggested for the PCEA technique, and currently, no consensus exists on whether use of a basal infusion is worthwhile.

• Several recommended options for PCEA dosing during labor are listed in Table 3-6. The same drug solutions used for continuous infusion epidural analgesia are usually also used for PCEA.

• One study reported no benefit from using a basal infusion (32), but another study found that less physician-administered boluses were required when a basal infusion of 6 mL/h was included in the PCEA dosing regimen (33).

• The need for a basal infusion during PCEA is largely determined by the motivation level of patients to be actively involved in their pain management.

• The newest dosing strategy for epidural labor analgesia is PCEA + automated intermittent mandatory boluses. Compared to PCEA with basal infusion, this technique has been shown to increase patient satisfaction and decrease total local anesthetic dose (34). Larger boluses administered over longer time intervals (10 mL bolus every 60 minutes) provide equivalent pain relief with less local anesthetic consumption compared to smaller boluses administered over shorter intervals (2.5 mL every 15 minutes or 5 mL every 30 minutes) (35). Because commercially available pumps that can be programmed for this dosing technique have just recently been approved for use in the United States, it is not yet clear how frequently used this labor analgesia technique will become.

Table 3-5 Recommended Dosing for Continuous Infusion Epidural Labor Analgesia

Table 3-6 Suggested Dosing Strategies for PCEA

PCA, patient-controlled analgesia.

Combined Spinal–Epidural Analgesia

• CSE analgesia is another commonly used technique for labor analgesia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree