Obesity in children 2 to 19 years of age is defined as a BMI ≥the 95%ile using age- and sex-specific growth charts. If the same BMI criteria used for adult obesity (BMI >30) is used for the 12 to 19 year olds, they have a fairly high prevalence of 13.9% (95% CI, 10.9-17.7) of obesity and further risks of increasing BMI with each subsequent pregnancy.3

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Obesity and excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) synergistically and independently contribute to adverse maternal, neonatal, and infant outcomes. However, obesity alone contributes to increased risks of miscarriage, thromboembolism, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, dysfunctional labor, cesarean section, postpartum hemorrhage, anesthetic complications, postpartum infection, and neonatal death. Congenital anomalies are noted more frequently in the fetuses of obese women compared with normal weight women with the risk of neural tube defects almost doubled. 9–11

Stillbirth is also noted more frequently among obese pregnancies with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.07 (95% CI, 1.59-2.74).12 Further, in a recent systematic review, increased maternal BMI was associated with increased fetal death, stillbirth, and infant death. This systemic review accessed primarily cohort studies, defined fetal death as a spontaneous fetal death during pregnancy or labor, stillbirth as fetal death greater than 20 weeks of gestation and infant death as death of a live born between birth to 1 year. Relative risk for infant demise increased with each five unit increase in maternal BMI and was most pronounced for a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or greater as shown by the following: fetal death 3.54 (95% CI, 2.56-4.89), stillbirth 2.19 (95% CI, 2.03-2.36), and infant death 1.95 (95% CI, 1.73-2.19).13

MANAGEMENT

In the past, obesity was simply considered as a state of energy imbalance, with excessive nutrient or energy intake outpacing energy expenditure. However, recently, the American Medical Association has taken the necessary steps to identify obesity as a disease worthy of a full range of medical interventions for both treatment and prevention. Management of the overweight and obese pregnant woman is particularly important due to increased maternal and infant morbidity associated with obesity.

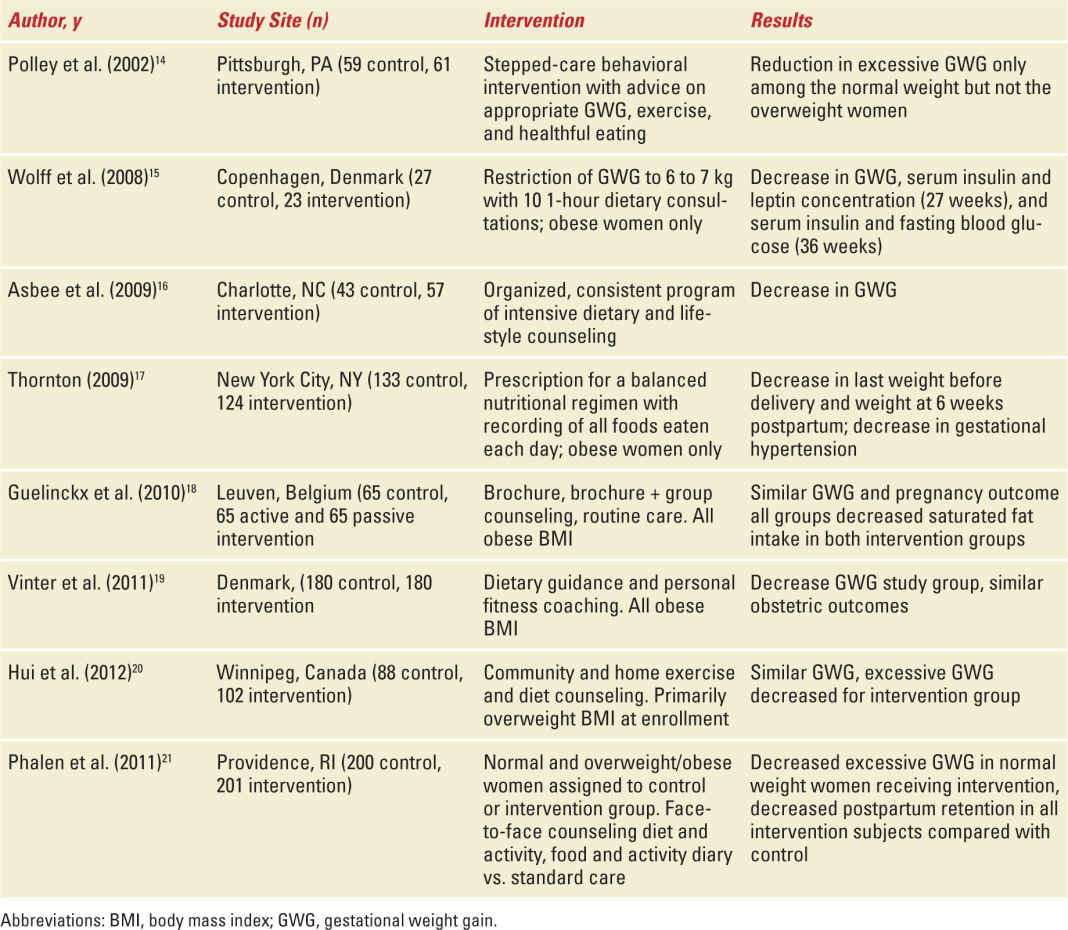

Lifestyle modification and educational trials have been conducted during pregnancy with the aim of affecting GWG and pregnancy outcome. Although dietary adjustments targeted for weight loss are not recommended during pregnancy, nutritional education to maintain GWG within the recommended limits of the Institute of Medicine guidelines is warranted. Available randomized trials focused on type and duration of lifestyle modification during pregnancy have yet to be completed. Randomized trials involving obese pregnant women (Table 17-2) have met with varying success but have not resulted in additional adverse outcomes. Two recent systematic reviews of this topic show conflicting results for diet and physical activity modifications effectively improving pregnancy outcome or reducing GWG, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and preterm birth without introducing other adverse effects. 22,23 Finally, it is possible to introduce an intervention that increases adverse pregnancy outcome. Antenatal dietary and supplementation advice as reviewed by the Cochrane group suggests that advice aimed at a balanced diet with appropriate macronutrients is effective at increasing maternal protein intake and reducing preterm birth. A balanced protein supplementation also appeared to improve prenatal growth and decrease stillbirth. However, high protein and an unbalanced supplementation were not beneficial and seemed associated with increased risk for small for gestational age infants.23

TABLE 17-2 | Lifestyle Intervention Studies During Pregnancy |

Although a specific lifestyle intervention best adapted for use during pregnancy has not been identified, nutritional education should always be addressed as a part of prenatal care.

First, the nutritional needs of the patient will need to be identified. The daily requirement for energy is defined as the estimated energy requirement (EER). The EER accounts for individual energy intake, energy expenditure, age, gender, weight, height, level of physical activity, and special conditions such as pregnancy. Consuming in excess of one’s EER results in weight gain.24 The EER needs during pregnancy were determined by using the combined information derived from total energy requirements (TEE) of nonpregnant women plus the changes in TEE during pregnancy as identified by studies using double labeled water in several hundred pregnant women.25

During the first trimester of pregnancy, the EER is similar to nonpregnant levels but will increase by 340 kcal/day in the second trimester and 452 kcal/day in the third trimester. This is an approximate overall increase of 77 to 80,000 kcal during the entire course of pregnancy and generally translates into a daily requirement between 2200 and 2900 kcal for most pregnant women.25 For example, a 30-year-old, nonpregnant, 5 foot 4 inch woman, weighing 200 pounds, and admitting to low activity would have an EER of approximately 2400 kcal. In her first trimester, the EER will remain 2400 kcal, while during the second and third trimesters, it will increase to 2740 and 2852 kcal, respectively. In the course of discussing nutrition with a patient you will encounter macronutrients (carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) and micronutrients (iron, folate, calcium, vitamin D, and others) which will likely be expressed as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs), Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA), and Adequate Intake (AI), Tolerable Upper Intake Level, or Estimated Average Requirement.25,26

Acceptable macronutrient distribution ranges for adults have been estimated as follows: carbohydrate 45%-65%, fat 20%-35%, and protein 10%-35% (average 15%).8,24 During pregnancy, the DRIs for macronutrients can also be expressed as carbohydrate 175 g/day (RDA), fats as linoleic acid 13 g/day (AI) and α- linolenic acid 1.3 g/day (AI), and protein 71 g/day (AI).24 The requirement for folic acid and iron roughly double while the requirements for the following nutrients increase but to a lesser degree: calcium, phosphorus, iodine, thiamin, zinc, magnesium, vitamin C, and pyridoxine.27

Nutritional counseling needs to be culturally sensitive and individualized, developing strategies to identify food adaptations for each patient.28 Food choices have changed dramatically over the past two decades, fast food options are readily available, are often chosen over other nutritional choices, and when used on a weekly basis are associated with increasing obesity. It is important that food choices be nutrient dense. The top 10 out of the 25 most frequently listed food choices by adults 19 years and older, as listed in the USDA Dietary Guidelines include: grain and dairy-based desserts, yeast breads, chicken dishes, alcoholic beverages, pizza, tortillas, pasta, and beef dishes.29 Many of these foods are nutrient poor food choices, meaning they offer calories but few micronutrients. Nutritional counseling can be difficult in a busy setting with limited resources but can be streamlined using patient educational brochures from reputable sources such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) or USDA and online sources such as www.choosemyplate.gov.29 The site www.choosemyplate.gov has replaced “my pyramidplaced “my gov.choosemyplate.gov”d Gynecologists (es from reputable sources such as cronutrients. es are often chosen over othe, as well as detailed nutritional reports.

EXERCISE

The ACOG recommends 30 minutes or more of moderate exercise a day for pregnant women.30 This is consistent with recommendations from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association for exercise in healthy adults aged 18 to 65 years to participate in moderate intensity activity at least 5 days a week.31 During pregnancy, exercise should only be undertaken in the absence of contraindications to aerobic exercise such as significant heart or lung disease, obstetric complications, extreme morbid obesity, sedentary lifestyle, orthopedic limitations, and poorly controlled comorbid medical conditions. Contact sports or activities with an increased risk of falling should best be avoided during pregnancy.30

Studies have shown that the physical activity of most pregnant women does not meet the above recommendations, and sedentary habits increase in the third trimester. Aerobic exercise may be difficult for the extreme obese individual due to locomotive limitations and muscle deterioration, but progressive resistance training may work well for this group improving muscle strength.31

Detection of congenital anomalies becomes more difficult with increasing BMI. Dashe et al. demonstrated decreasing ability to visualize fetal anatomy with approximately 50% or more of the anatomy of interest not clearly seen in obese individuals.32 In some cases, using the maternal umbilicus as a window to improve ultrasound transmission can enhance imaging. The umbilicus is filled with ultrasound gel after which a transvaginal probe is inserted into the umbilicus. In a small study by Rosenberg et al, this improved visualization of the fetal heart.33

Labor has been studied in obese, overweight, and normal weight women noting no difference between groups in terms of uterine contractility. A longer active phase of labor was noted in the obese group, but ultimately no difference in the second stage or operative delivery rates was found.34 Cesarean delivery rate is increased in obese and morbidly obese women compared with normal weight women (33.8% and 47.4% vs. 20.7%, respectively).35 Postoperative infectious morbidity is also increased two- to threefold when the BMI >30 kg/m2.36 Postoperative morbidity and the approach to the skin incision warrants further discussion for the obese patient. The characteristics of the pannus create challenges for placement of the skin incision and subsequently the location of the uterine incision. First is the choice of skin incision. Two primary incisional choices are the low transverse or vertical skin incision. Comparisons between the two methods show conflicting results. Wall et al. 37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree