Normal Infant and Childhood Development

Sharon B. Richter

Barbara J. Howard

Raymond Sturner

A major joy of pediatrics is observing and interpreting the child’s changing developmental abilities for the parents. A child’s development is based on changes in central nervous system maturation and myelination, modulated by interpersonal and environmental factors. What impacts the family are the continual and often sudden shifts in behavior, cognition, and emotional functioning. These changes result from neurologic readiness and then acclimatization to new experiences in all the child’s environments: home, peer groups, and school, as well as the larger macrosystem of the community and culture. Theories about the socioemotional development of children that describe development in terms of achieving different developmental tasks can be very helpful to recognizing what may be motivating a child or confronting a parent. Concepts of neuromaturation can be helpful in making observations of developmental progress and in assisting professionals in remembering typical ages for achieving that progress. Understanding the meaning of the child’s behavior is critical to a parent’s ability to adapt to or manage it optimally. Successful mastery of normal developmental tasks is considered necessary for the incorporation of new skills to form future developmental competencies. This progression leads to adaptive functioning in later life. This chapter will describe the normal course of development through these tasks as defined by Erikson.

BIRTH TO 18 MONTHS: FROM SURVIVAL TO EXPLORATION

Erik Erikson described the first major developmental task in life as establishing a sense of basic trust rather than remaining in mistrust. This is achieved when the caregiver is responsive to the needs of the baby. He describes this in his book Childhood and Society:

“The infant’s first social achievement, then, is his willingness to let the mother out of sight without undue anxiety or rage, because she has become an inner certainty as well as an outer predictability … Mothers create a sense of trust in their children by that kind of administration which in its quality combines sensitive care of the baby’s individual needs and a firm sense of personal trustworthiness within the trusted framework of their culture’s life style.”

The interactions that establish trust also form the basis for attachment. Attachment may be defined as the permanent affective two-way bond that connects people. For parents and infants, this bond develops through interaction over the first 1 to 2 years. Bonding refers to the special initial feelings of affection the caregiver has toward the infant. A sensitive—but not critical—period for the establishment of bonding appears to exist. This period covers the first hours and days of the infant’s life and is enhanced by early infant alertness, skin-to-skin contact, and long opportunities to be with the parent, such as when rooming-in after birth. While bonding sets the stage for attachment, it is not essential, as clearly evident in securely attached children who are adopted at later ages. The primary attachment relationship is an important foundation and model for the establishment of trust in others and the understanding of self. Research associates later secure patterns of attachment with repeated early experiences of receiving prompt and sensitive care contingent to the infant’s signals of need. When infants experience care unpredictably or care that does not meet their needs, they are more likely to develop a pattern of insecure attachment that, while still considered normal, is associated with less optimal outcomes.

The attachment patterns that develop in infancy have effects into childhood and even into adult life. Secure attachment also leads to a more cooperative relationship between the parent and child. Thus, the degree of attachment has important implications as it affects parental discipline and how the child will conform to family norms. Young children with secure patterns of attachment are more social and more popular during the preschool years and show more joy in mastery of tasks. They have also been shown to have better relationships with other adults and authority figures such as teachers and camp counselors. Apart from relating to others, children who are securely attached develop a better self-concept and emotional maturity than those who are not securely attached. Thus, how a parent responds to an infant sets the stage for how the child sees him or herself and expects his or her needs to be filled in the future.

These basic needs of infancy that must be consistently and warmly met for a secure attachment pattern to develop are discussed in the following sections.

Need for State Regulation

Within the first 2 to 3 months of life the major developmental tasks are physiologic regulation, state regulation, motor regulation, and interaction. For example, physiologic regulation describes emerging control over the survival functions of regular breathing, bowel motility, temperature control, sucking, and swallowing that mature with time. State regulation refers to the infant’s level of alertness and ability to modulate changes from one level of arousal to another. States range from deep sleep, to restless sleep, drowsiness, alertness, fussiness, and restlessness, to full crying.

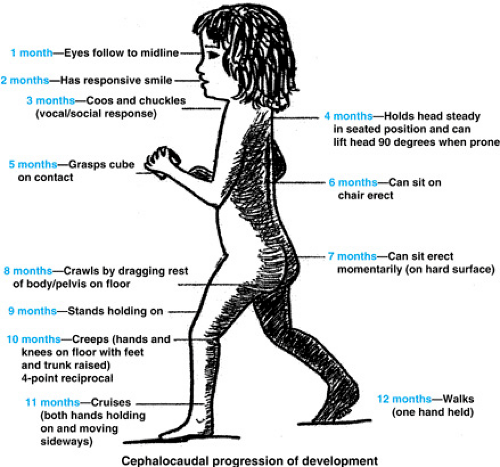

At birth, infants have the capacity to come to an alert state for brief periods during which they can actively fixate on and search the faces of their caregivers, follow slowly moving targets laterally with their eyes, and localize sounds by turning their heads when human voice range is presented for several seconds. It can be easily recalled that in the first 3 months the major attainments are in the control of the oculomotor system and state (Fig. 96.1; think “eyes”). Over the first few weeks, the periods of alertness increase and attentional/interactive regulation improves with faster and more reproducible fixing and following. At 6 weeks postterm the gaze at the caregiver results in responsive smiling (think “mouth”). By 2 months infants track

with their eyes past the midline, and by 4 months tracking is reliable for 180 degrees horizontally and vertical tracking is also possible. State control is more evident in longer bouts of sleep at night, even though total sleep is unchanged, and in more robust alertness during the day. The success of how parents help their infant regulate state cycles by setting routines of eating and sleeping, providing salient visual stimuli (such as faces and high-contrast rounded shiny objects), and avoiding overstimulation (such as excessive noise or handling) contribute to the development of attachment. Assistance with regulation of state is especially important for infants prone to suboptimal state control, such as those who are temperamentally irregular or have trouble adapting and those with neurologic damage, or neurotoxin or neuropharmacologic effects such as lead poisoning, or prenatal substance exposure.

with their eyes past the midline, and by 4 months tracking is reliable for 180 degrees horizontally and vertical tracking is also possible. State control is more evident in longer bouts of sleep at night, even though total sleep is unchanged, and in more robust alertness during the day. The success of how parents help their infant regulate state cycles by setting routines of eating and sleeping, providing salient visual stimuli (such as faces and high-contrast rounded shiny objects), and avoiding overstimulation (such as excessive noise or handling) contribute to the development of attachment. Assistance with regulation of state is especially important for infants prone to suboptimal state control, such as those who are temperamentally irregular or have trouble adapting and those with neurologic damage, or neurotoxin or neuropharmacologic effects such as lead poisoning, or prenatal substance exposure.

Behavioral concerns parents may have related to state regulation include excessive crying and colic. Normal crying increases at 2 weeks postterm age and peaks around 6 to 8 weeks at 2¾ hours per day. It is usually worse at 6 to 11 PM at night. Crying decreases coinciding with increasing capacity to supress responses to sensory stimuli and new neural organization seen by such markers as a more adult-like EEG and visual evoked responses seen by 3 months of age and by the emergence of cooing and more hand-to-mouth movements and sucking. Parents can help reduce crying by swaddling tightly, providing white noise or shushing, vestibularly stimulating in the form of rocking or gentle swinging, or offering a finger or pacifier to suck.

Colic is defined as crying that is greater than or equal to 3 hours per day, 3 or more days per week for at least 3 weeks. Colic researchers usually also require additional signs such as burping, a reddened face, pulling the legs up to the stomach, and inconsolability to fully define colic. Crying reduces to 1 hour per day on its own by 4 months as the baby develops increased control over arousal, but colic-type crying may persist to 6 months. Although medications do not reliably reduce colic, use of hydrolysate formula in addition to the consoling techniques previously described can help.

Sleep problems are another manifestation of emerging state regulation early in infancy but can easily become learned behavior even in the first 4 months. Initial regulation issues manifest as day–night reversal, but by 4 months postterm infants can have trained night feeding if it is reinforced by feeding and trained night waking if it is reinforced by attention and play. When object permanence is established around 8 to 10 months, night crying that is easily consoled can best be resolved over a 4 to 5 day stretch by allowing the baby to adapt to silent parental company if the infant does not return to sleep on his own. All sleep problems can be complicated by sleep associations after 2 months of age if infants are not helped to learn to fall asleep on their own by being placed in bed awake.

By 12 months of age state regulation problems manifest as temper tantrums, which are common as children’s ideas overwhelm their abilities to do or say and their ability to control the resulting feelings. Parents should be advised that providing consistent rules helps reduce frustration and encourages the development of self-regulation. Although parents should not give in to the demands that result in temper tantrums, they can sympathize with and hold their child without reinforcing tantrum behavior. Children’s efforts to regulate their own state—thumb sucking, head banging, rocking, masturbating—may be seen as problems by their caregivers (see later).

Need for Positive Emotional Tone and Need for Assistance Regulating Negative Affect

All children have a need for a positive emotional tone from their caregivers and assistance in regulating their negative affect. Positive emotional tone encourages development of secure attachment and enhances resilience under stress, which

otherwise can evoke negative affect and aggression. When infants are unable to regulate their own negative emotions, assistance from their caregivers occurs through parental techniques of avoiding stress, distracting, and modeling coping strategies. Caregivers should acknowledge and verbalize the feelings their child is experiencing, thus giving the message that the child is understood and cared about. Excess hostility in the family raises tension and models aggression and may bring about an insecure attachment. Corporal punishment includes pain that can increase aggression and negative affect (Table 96.1).

otherwise can evoke negative affect and aggression. When infants are unable to regulate their own negative emotions, assistance from their caregivers occurs through parental techniques of avoiding stress, distracting, and modeling coping strategies. Caregivers should acknowledge and verbalize the feelings their child is experiencing, thus giving the message that the child is understood and cared about. Excess hostility in the family raises tension and models aggression and may bring about an insecure attachment. Corporal punishment includes pain that can increase aggression and negative affect (Table 96.1).

TABLE 96.1. NORMAL MILESTONES AT 3 TO 12 MONTHS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Need for Mastery

By 9 months of age infants have an increased need for mastery. A common example of conflict from this occurs around feeding, even to the point of failure to thrive when infants are not allowed to exercise mastery over newly developed skills such as feeding themselves. If parents are unable to let them do this—most commonly because they want to avoid a mess or they are afraid that their child is not eating enough—then infants may actually refuse food. The solution is mandating self-feeding. To do this the anxious caregiver may need to read a magazine or do chores nearby to avoid showing concern or taking over the feedings.

Over the first 18 months of life, advances in cognitive, motor, and language development allow the infant to learn about and master the environment through sensory and motor exploration. Some principles about this developmental process are useful to recognize. An infant’s response to outside stimuli progresses from generalized reflexes involving entire body movements to localized voluntary actions that are under more control. This allows the infant to develop intentional and precise movements. As the central nervous system (CNS) matures, afferent nerves undergo myelination before efferent nerves, explaining why sensory perception precedes motor development. For example, ocular combining (i.e., comparing objects visually) occurs before motor grasp (i.e., combining the hand with the object physically). As the efferent nerves are myelinated, development proceeds in a cephalocaudal–proximal–distal direction. This is seen as babies gain head control before trunk control and gain trunk control before they can reach with their hands. Development occurs in a continuous fashion, building on what has gone before; thus, premature infants can be expected to attain milestones at a chronologic age that is adjusted for their weeks of prematurity throughout life (although the adjustment becomes insignificant after about age 2 years). The sequence of attaining milestones of development is always the same in normally developing children, but there is a range in the age at which this occurs. In this chapter all ages should be considered typical of the range rather than defining norms. It is now evident that progress, even including physical growth, normally occurs in spurts with plateaus in progress in between.

Gross Motor Development

Gross motor development from 3 to 6 months extends caudally to include the neck and upper trunk, including the arms, and is characterized by extensor control emerging before control of flexor muscles. Thus, the head is lifted up 90 degrees when prone at 4 months (think “neck”) before head lifts forward when supine at 5 months. Increasing abilities caudally in the lower back and legs allow supported sitting by 6 months (think “upper trunk”) and unsupported sitting at 7 months (think “lower trunk”). The chest is held off the table and swimming

movements occur when prone at 5 months. Development at 6 to 9 months includes distal control of the entire trunk and fingers such that after 6 months the infant can explore his or her world by drag crawling (think “pelvis”) and by 9 months can stand with support (think “knees”). Around 10 months the child can creep, often in an odd way (think “put all together”) and is soon able to pull to stand and cruise (think “ankle”). At 9 to 12 months distal control is completed, all the way to the feet for walking and fingers for pincering. Learning to stand alone and then walk by 12 months (think “toes”) is the most notable gross motor milestone of the first year of life for parents. Once an infant begins to practice walking, the process seems to fuel itself, often replacing all other developmental progress for weeks at a time. Carrying, holding, or diapering an autonomy-driven 12-month-old can be almost impossible and can require jollying, distraction, fast action, and above all a sense of humor.

movements occur when prone at 5 months. Development at 6 to 9 months includes distal control of the entire trunk and fingers such that after 6 months the infant can explore his or her world by drag crawling (think “pelvis”) and by 9 months can stand with support (think “knees”). Around 10 months the child can creep, often in an odd way (think “put all together”) and is soon able to pull to stand and cruise (think “ankle”). At 9 to 12 months distal control is completed, all the way to the feet for walking and fingers for pincering. Learning to stand alone and then walk by 12 months (think “toes”) is the most notable gross motor milestone of the first year of life for parents. Once an infant begins to practice walking, the process seems to fuel itself, often replacing all other developmental progress for weeks at a time. Carrying, holding, or diapering an autonomy-driven 12-month-old can be almost impossible and can require jollying, distraction, fast action, and above all a sense of humor.

Fine Motor Development

Advances in fine motor control proceed distally along with inhibition of the opposite extremity to make object exploration possible for the baby. In the concept of continuous development, consider that primitive reflexes may assist this increased control (e.g., the asymmetric tonic neck reflex places the hand in view on the extended arm the baby faces; a parachute response is needed to be safe when learning to walk). Primitive reflexes are often incorporated into subsequent voluntary movements (e.g., the reflex grasp becoming the voluntary grasp). Inhibition of primitive reflexes is often needed for normal movement patterns to proceed (e.g., inhibition of the reflex grasp is needed to acquire a voluntary release; inhibition of the asymmetric tonic neck reflex is needed to roll over). Babies continue to explore by putting their fingers into everything they can, a drive that should not be interpreted as willful hurting or misbehavior. The period between 3 and 6 months is also the time when fine motor capabilities develop rapidly (think “hand”), progressing from barely detectable, prereach movements of the fingers at 3 months, to batting, bilateral reaching, and midline play at 4 months, to the ability to reach with the closer hand at 5 months, to a unilateral reach at 6 months. Fine motor progresses as more precise coordination of the hand makes it possible to pick up small objects. The superior overhand index finger–thumb pincer grasp is perfected by 1 year. At 12 months, children can make stabbing marks on paper with a pencil. By 15 months, they are able to control the pencil enough for scribbling marks, and at 18 months, they can imitate marks on paper. Fundamental manipulative skills reach adult levels by the end of infancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree