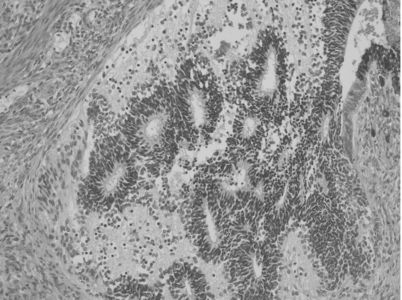

Figure 11.1 Schiller-Duvall bodies, papillary structures with central blood vessels, are seen in the endodermal sinus pattern of yolk sac tumor.

Embryonal Carcinoma

Embryonal carcinoma is rarely seen in the ovary. On gross examination, embryonal carcinoma characteristically displays areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. Microscopically, this tumor is composed of very crowded cells that display overlapping nuclei in paraffin sections. The nuclei are very pleomorphic, and they contain large, prominent nucleoli. The mitotic rate is high in these tumors. Glandular, solid, and papillary patterns may be seen. Vascular invasion is common. Embryonal carcinoma stains positively for PLAP, pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3 and CAM 5.2), CD30, and OCT3/4. Some embryonal carcinomas display focal AFP positivity that may represent partial transformation to yolk sac tumor. Syncytiotrophoblast cells may be present, resulting in positive stains for hCG.

Polyembryoma

Polyembryoma is a very rare malignant ovarian tumor. In the few cases reported, the embryoid bodies characteristic of this germ cell tumor have coexisted with other germ cell tumor types. The microscopic appearance of embryoid bodies with an embryonic disc separating a yolk sac and an amniotic cavity may actually be due to an admixture of yolk sac tumor and embryonal carcinoma.

Choriocarcinoma

Primary nongestational ovarian choriocarcinoma is rare. It is most often seen as a component of mixed germ cell tumors of the ovary. Choriocarcinomas display abundant hemorrhage and necrosis on gross examination. Microscopically, these neoplasms show a plexiform pattern composed of an admixture of syncytiotrophoblast and cytotrophoblast cells. Numerous mitoses are usually easily identified in the histologic specimen. These tumors produce hCG due to the presence of syncytiotrophoblast cells. Choriocarcinoma may also stain for cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen. Nongestational choriocarcinoma must be distinguished from gestational choriocarcinoma because the former has a worse prognosis and requires more aggressive therapy. The identification of paternal genetic material indicates that the tumor is of gestational origin.

Mixed Germ Cell Tumors

Mixed germ cell tumors of the ovary contain two or more different types of germ cell neoplasm, either intimately admixed or as separate foci within the tumor. They are much less common in the ovary than in the testis, accounting for only about 8% of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors.

The diagnosis and prognosis of malignant mixed germ cell tumors depend on adequate tumor sampling in order to detect small areas of different types of germ cell tumor because the types of tumor identified may affect therapy and prognosis.

Teratomas

Teratomas are germ cell tumors that contain tissue derived from two or three embryonic layers. Teratomas are subclassified according to whether the tumor elements represent mature or immature tissue types. In addition, some teratomas are composed of a predominance of one tissue type such as thyroid tissue (struma ovarii).

Most teratomas are mature cystic teratomas that contain differentiated tissue components such as skin, cartilage, glia, glandular elements, and bone. Any tissue type present in adults may be represented in teratomas. Mature cystic teratomas represent benign neoplasms unless they contain a somatic malignancy such as squamous carcinoma, papillary thyroid carcinoma, or other non–germ cell tumors arising in differentiated elements of the teratoma.

ITs in adult women, in contrast to mature cystic teratomas, are uncommon tumors. They represent only about 3% of all ovarian teratomas, but ITs are the third most common form of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors.

Most immature ovarian teratomas are unilateral, although they can metastasize to the opposite ovary and can also be associated with mature teratoma in the opposite ovary. They are predominantly solid tumors, but they may contain some cystic areas. The cut surface of an IT is soft and fleshy in appearance. Areas of hemorrhage and necrosis are common. Microscopically, these tumors contain a variety of mature and immature tissue components. The immature elements almost always consist of immature neural tissue in the form of small round blue cells focally organized into rosettes and tubules (Fig. 11.2). There is a correlation between the disease prognosis and the degree of immaturity in the teratoma.

Figure 11.2 Ovarian IT. Immature neural tissue forms tubules.

A three-tiered grading system is still the one most often used:

- Grade 1 neoplasms display some immaturity, but the immature neural tissue does not exceed in aggregate the area of one low-power field (40×) in any slide.

- Grade 2 teratomas contain more immaturity, but immature neural tissue occupies no more than an area equal to three low-power fields in any slide.

- Grade 3 neoplasms contain immature neural tissue that occupies an area greater than three low-power fields in at least one slide.

The amount of mitotic activity and immature neural tissue (characterized as rosettes and tubules) increases with increasing tumor grade. In patients whose neoplasm has disseminated beyond the ovary, the grade of the tumor metastasis is important in predicting survival and determining treatment. Occasionally, patients may have peritoneal implants that contain only mature tissue, but these mature glial implants may represent host tissue and not actual tumor implants. It is extremely important to sample peritoneal disease thoroughly in order that foci of IT (that may coexist with mature glia) are identified.

Sex Cord–Stromal Tumors

The current World Health Organization classification of ovarian sex cord–stromal tumors includes granulosa cell tumors, thecomas, fibromas, sclerosing stromal cell tumors, Sertoli cell tumors, Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors, sex cord tumors with annular tubules, gynandroblastomas, and steroid cell tumors.

Granulosa Cell Tumors

Granulosa cell tumors comprise 5% of all ovarian malignancies, but account for approximately 70% of malignant sex cord–stromal tumors. The peak incidence for these tumors occurs during the perimenopausal decade. They are subdivided into adult type and juvenile type.

The majority of patients with adult-type granulosa cell tumors present with one or a combination of the following clinical findings: abnormal vaginal bleeding, abdominal distention, and abdominal pain. The endocrine function of adult-type granulosa cell tumors, specifically the production of estrogens, has been demonstrated by assessments of the end organ, the endometrium, and measurements of peripheral levels of estrogen. Adult-type granulosa cell tumors have an average diameter of 12 cm. They are predominately cystic, with numerous loculi filled with fluid or blood and separated by solid tissue. The solid tissue may be gray-white or yellow and soft or firm. Microscopic examination reveals a population of granulosa cells often with an additional component of theca cells, fibroblasts, or both. In well-differentiated tumors, the granulosa cells have a microfollicular pattern characterized by numerous small cavities (Call-Exner bodies).

Approximately 90% of the granulosa cell tumors diagnosed in prepubertal girls and women less than 30 years of age will be of the juvenile type. The majority of prepubertal patients present with clinical evidence of isosexual precocious pseudopuberty. Serum estradiol levels are reported as increased in these cases with pseudopuberty. The appearance of juvenile-type granulosa cell tumors is similar to the adult form: a solid and cystic neoplasm in which cysts contain hemorrhagic fluid. Microscopic examination typically reveals a predominately solid cellular tumor with focal follicle formation. Call-Exner bodies are rarely encountered.

Thecoma

Theca cell tumors, or thecomas, are composed of lipid-laden stromal cells, occasionally demonstrating luteinization, and are almost invariably clinically benign. Thecomas account for approximately 1% of ovarian neoplasms. The primary presenting signs and symptoms are abnormal vaginal bleeding and/or pelvic mass. Thecomas are considered to be among the most hormonally active of the sex cord–stromal tumors.

Fibroma–Fibrosarcoma

Fibromas are the most commonly encountered sex cord–stromal tumor, accounting for approximately 4% of all ovarian neoplasms. These endocrine- inert tumors are seldom bilateral and vary in size. As their size increases, fibromas tend to become more edematous, leading to the escape of increasing quantities of fluid from the tumor surfaces. Ascites is detected with 10% to 15% of ovarian fibromas exceeding 10 cm. Furthermore, 1% of patients develop a hydrothorax in addition to hydroperitoneum (Meigs syndrome).

Ovarian fibromas are generally benign, but 10% will demonstrate increased cellularity and varying degrees of pleomorphism and mitotic activity. Fibromatous tumors characterized histologically by an increased cellular density and brisk mitotic activity are considered to be of low malignant potential. In contrast, fibrosarcomas are highly malignant neoplasms distinguished by their greater cellular density and marked pleomorphism.

Sclerosing Stromal Tumors

Accounting for less than 5% of sex cord–stromal tumors, sclerosing stromal cell tumors are a rare tumor characteristically different from both thecomas and fibromas. Histologically, the presence of pseudolobulation of cellular areas separated by edematous connective tissue, increased vascularity, and prominent areas of sclerosis are distinguishing features. The signs and symptoms that most commonly necessitate medical evaluation include menstrual irregularities and/or pelvic pain.

Sertoli Cell Tumors

Sertoli cell tumors are rare. Evidence of estrogen production is observed in approximately two thirds of cases. Consistent with estrogen excess, isosexual precocious puberty has been witnessed during the first decade of life, menstrual disorders during the reproductive decades, and postmenopausal bleeding in the decades after the climacteric. These rare tumors are typically solid, lobulated, and yellow.

Sertoli–Leydig Tumors

Sertoli–Leydig tumors are extremely uncommon, accounting for less than 0.2% of all ovarian tumors. As implied by their designation, the tumors contain both Sertoli and Leydig cell elements. The average patient age at diagnosis is approximately 25 years old. The most frequent complaints at the time of presentation are menstrual disorders, virilization, and nonspecific symptoms resulting from abdominal mass. Frank virilization occurs in 35% of the patients with Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors, and another 10% to 15% have some clinical manifestations consistent with androgen excess. The majority of these tumors are solid, often yellow, and lobulated. Well-differentiated Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors are characterized by a predominately tubular pattern. A nodular architecture is often conspicuous, with fibrous bands intersecting lobules composed of small, round, hollow, or—less often—solid tubules, separated by Leydig cells.

Sex Cord Tumor with Annular Tubules

These unique ovarian tumors are characterized by either simple or complex ring-shaped tubules, giving them the morphologic designation ovarian sex cord tumor with annular tubules. The distinctive cellular elements of these neoplasms are judged to be histologically representative of an intermediate between Sertoli cell tumors and granulosa cell tumors. Approximately one in three sex cord tumors with annular tubules occurs in association with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Abnormal vaginal bleeding is the most common presenting complaint, including menstrual irregularities during the reproductive era and postmenopausal bleeding during the mature years.

Gynandroblastoma

Gynandroblastoma is an extremely rare sex cord–stromal tumor. Microscopically these tumors must demonstrate readily identifiable granulosa cells and tubules of Sertoli cells. Patients present at an average age of 29.5 years with primary symptoms of menstrual disturbances consistent with the predominant functional status of the tumor.

Steroid Cell Tumors

Steroid cell tumors constitute only 0.1% of all ovarian neoplasms. The predominant components of these tumors are steroid hormone–secreting cells including lutein cells, Leydig cells, and adrenocortical cells. Steroid cell tumors are stratified into subclasses based on their hormone secretion.

Stromal luteomas are relatively small (<3 cm) tumors localized within the parenchyma of the ovary, accounting for approximately 25% of steroid cell tumors. Eighty percent occur after the climacterium. The predominant functional profile is estrogenic, with abnormal vaginal bleeding being the primary complaint.

Leydig cell tumors account for 15% to 20% of steroid cell tumors. Histologically, the cellular elements are indistinguishable from lutein cells or adrenocortical cells except for the presence of crystals of Reinke. The initial clinical manifestations are usually consistent with a hyperandrogenic state. Overt signs of virilization are observed in over 80% of the patients.

Neoplasms identified as steroid cell tumors but lacking the specific characteristics of stromal luteomas or Leydig cell tumors are collectively classified as steroid cell tumors not otherwise specified. These generally solid yellow tumors are larger than other steroid cell tumors, with a higher frequency of bilaterality. Clinical signs and/or symptoms of androgen excess ranging from heterosexual precocity in prepubertal girls to amenorrhea, hirsutism, and virilization during the reproductive and postmenopausal ages prompt the majority of patients to seek medical advice.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF GERM CELL TUMORS

KEY POINTS

- Germ cell tumors account for 2% to 3% of all ovarian cancers and usually occur in girls or young women.

- Most patients present with stage I disease.

- hCG and AFP are useful tumor markers for some subsets of germ cell tumors.

Abdominal pain associated with a palpable pelvic–abdominal mass is present in approximately 85% of patients with germ cell tumors. Approximately 10% of patients present with acute abdominal pain, usually caused by rupture, hemorrhage, or ovarian torsion. This finding is somewhat more common in patients with endodermal sinus tumor or mixed germ cell tumors. Less common signs and symptoms include abdominal distention (35%), fever (10%), and vaginal bleeding (10%). A few patients exhibit isosexual precocity, presumably due to hCG production by tumor cells.

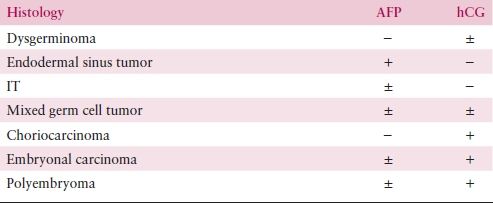

Many germ cell tumors possess the unique property of producing biologic markers that are detectable in serum. The development of specific and sensitive radioimmunoassay techniques to measure hCG and AFP led to dramatic improvement in patient monitoring. Serial measurements of serum markers aid the diagnosis and, more importantly, are useful for monitoring response to treatment and detection of subclinical recurrences. Table 11.1 illustrates typical findings in the sera of patients with various tumor histologic types. Endodermal sinus tumor and choriocarcinoma are prototypes for AFP and hCG production, respectively. Embryonal carcinoma can secrete both hCG and AFP, but most commonly produces hCG. Mixed tumors may produce either, both, or none of the markers, depending on the type and quantity of elements present. Dysgerminoma is commonly devoid of hormonal production, although a small percentage of tumors produce low levels of hCG. The presence of an elevated level of AFP or high level of hCG (>100 U/mL) denotes the presence of tumor elements other than dysgerminoma. Therapy should be adjusted accordingly. Although ITs are associated with negative markers, a few tumors can produce AFP. A third tumor marker is lactic dehydrogenase, which is frequently elevated in patients with dysgerminoma or other germ cell tumors. Unfortunately, it is less specific than hCG or AFP, which limits its usefulness. CA-125 can also be nonspecifically elevated in patients with ovarian germ cell tumors.

Table 11.1 Serum Tumor Markers in Malignant Germ Cell Tumors of the Ovary