Chapter 584 Neurologic Evaluation

History

The history should begin with the chief complaint, as well as a determination of the complaint’s relative significance within the context of normal development (Chapters 7–14). The latter step is critical because a 13 mo old who cannot walk may be perfectly normal, whereas a 4 yr old who cannot walk might have a serious pathology.

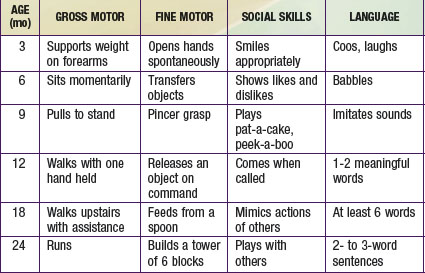

The most important component of a neurologic history is the developmental assessment (Chapters 6 and 14). Careful evaluation of a child’s social, cognitive, language, fine motor, and gross motor skills is required to distinguish normal development from either isolated or global (i.e., in two or more domains) developmental delay. An abnormality in development from birth suggests an intrauterine or perinatal cause, but a loss of skills (regression) over time strongly suggests an underlying degenerative disease of the CNS, such as an inborn error of metabolism. The ability of parents to recall the precise timing of their child’s developmental milestones is extremely variable. It is often helpful to request old photographs of the child or to review the baby book, where the milestones may have been dutifully recorded. In general, parents are aware when their child has a developmental problem, and the physician should show appropriate concern. Table 584-1 outlines the upper limits of normal for attaining specific developmental milestones. A comprehensive review of developmental screening tests and their interpretation is listed in Chapter 14.

Neurologic Examination

The neurologic examination begins at the outset of the interview. Indirect observation of the child’s appearance and movements can yield valuable information about the presence of an underlying disorder (Chapters 6 and 14). For instance, it may be obvious that the child has dysmorphic facies, an unusual posture, or an abnormality of motor function manifested by a hemiparesis or gait disturbance. The child’s behavior while playing and interacting with his or her parents may also be telling. A normal child usually plays independently early in the visit but will rapidly engage in the interview process. A child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder might display impulsive behavior in the examining room, and a child with neurologic impairment might exhibit complete lack of awareness of the environment. Finally, note should be made of any unusual odors about the patient, because some metabolic disorders produce characteristic scents (e.g., the “musty” smell of phenylketonuria or the “sweaty feet” smell of isovaleric acidemia). If such an odor is present, it is important to determine whether it is persistent or transient, occurring only with illnesses.

The examination should be conducted in a nonthreatening, child-friendly setting. The child should be allowed to sit where he or she is most comfortable, whether it be on a parent’s lap or on the floor of the examination room. The physician should approach the child slowly, reserving any invasive or painful tests (e.g., measurement of head circumference, gag reflex) for the end of the examination. In the end, the more that the examination seems like a game, the better the child will cooperate. Because the neurologic examination of an infant requires a somewhat modified approach from that of an older child, the two groups are considered separately (Chapters 7, 8, and 88).

Head

Correct measurement of the head circumference is important. It should be performed at every visit for patients younger than 3 yr and should be recorded on a suitable head growth chart. To measure, a nondistensible plastic measuring tape is placed over the mid-forehead and extended circumferentially to include the most prominent portion of the occiput. If the patient’s head circumference is abnormal, it is important to document the head circumferences of the parents and siblings. Errors in the measurement of a newborn skull are common owing to scalp edema, overriding sutures, and the presence of cephalohematomas. The average rate of head growth in a healthy premature infant is 0.5 cm in the 1st 2 wk, 0.75 cm in the 3rd wk, and 1.0 cm in the 4th wk and every week thereafter until the 40th wk of development. The head circumference of an average term infant measures 34-35 cm at birth, 44 cm at 6 mo, and 47 cm at 1 yr of age (Chapters 7 and 8).

If the brain is not growing, the skull will not grow; therefore, a small head reflects a small brain, or microcephaly. Conversely, a large head may be associated with a large brain, or macrocephaly, which is most commonly familial but may be due to a disturbance of growth, neurocutaneous disorder (e.g., neurofibromatosis), chromosomal defect (e.g., Kleinfelter syndrome), or storage disorder. Alternatively, the head size may be increased secondary to hydrocephalus (Fig. 584-1) or chronic subdural hemorrhages. In the latter case, the skull tends to assume a square or boxlike shape, because the long-standing presence of fluid in the subdural space causes enlargement of the middle fossa.

The shape of the head should be documented carefully. Plagiocephaly, or flattening of the skull, can be seen in normal infants but may be particularly prominent in hypotonic or weak infants, who are less mobile. A variety of abnormal head shapes can be seen when cranial sutures fuse prematurely, as in the various forms of inherited craniosynostosis (Chapter 585.12).

Cranial Nerves

Optic Nerve (Cranial Nerve II)

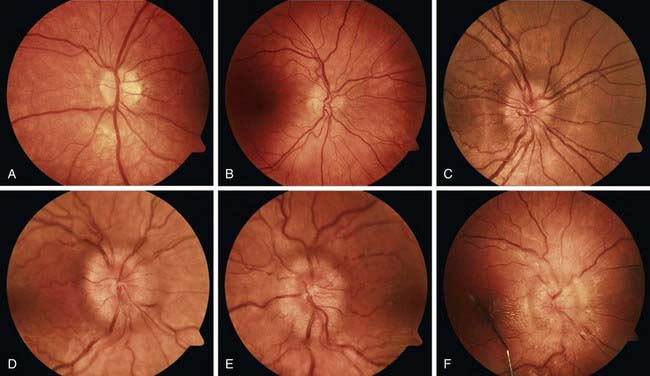

Disc edema refers to swelling of the optic disc, and papilledema specifically refers to swelling that is secondary to increased intracranial pressure. Papilledema rarely occurs in infancy because the skull sutures can separate to accommodate the expanding brain. In older children, papilledema may be graded according to the Frisen scale (Fig. 584-2). Disc edema must be differentiated from papillitis, or inflammation of the optic nerve. Both conditions manifest with enlargement of the blind spot, but visual acuity and color vision tend to be spared in early papilledema in contrast to what occurs in optic neuritis.

Oculomotor (III), Trochlear (IV), and Abducens Nerves (VI)

Disconjugate gaze can result from extraocular muscle weakness; cranial nerve (CN) III, IV, or VI palsies; or brainstem lesions that disrupt the medial longitudinal fasciculus. Infants who are <2 mo old can have slightly disconjugate gaze at rest, with one eye horizontally displaced from the other by 1 or 2 mm (strabismus). Vertical displacement of the eyes, known as skew deviation, is always abnormal and requires investigation. Strabismus is discussed further in Chapter 615.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

to 3 yr of age can identify the objects on a pediatric eye chart (Allen chart) at a distance of 15-20 ft.

to 3 yr of age can identify the objects on a pediatric eye chart (Allen chart) at a distance of 15-20 ft.