Neurocutaneous Syndromes

George E. Tiller

The neurocutaneous syndromes or phakomatoses (phakos, Gr., a lentil, or lentil-shaped spot) are a group of unrelated disorders characterized by congenital abnormalities of the skin and nervous system. Some are malformations or embryonic dysplasias and are associated with benign or malignant neoplasms. The most common neurocutaneous disorders include neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), tuberous sclerosis (TS), albinism, Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS), and neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). Other less commonly encountered neurocutaneous syndromes include Waardenburg syndrome, incontinentia pigmenti, hypomelanosis of Ito, ataxia-telangiectasia, von Hippel-Lindau (vHL) syndrome, and Proteus syndrome.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

All the neurocutaneous syndromes mentioned in the preceding text (except for SWS) have a genetic basis. Those that are associated with neoplasms (NF1, NF2, TS, vHL) are caused by mutations in tumor-suppressor genes. Some of these disorders (albinism, TS, Waardenburg syndrome) display genetic heterogeneity, meaning that a single mutation in one of several genes is responsible for the disease in a particular family or individual.

MORE COMMON NEUROCUTANEOUS SYNDROMES

Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Incidence: 1/3000

Inheritance: autosomal dominant

Features: neurofibromas, optic gliomas, café au lait spots, axillary and inguinal freckling, Lisch nodules, and osseous lesions

Primary defect: neurofibromin, a tumor-suppressor gene on chromosome 17

NF1 is the most prevalent neurocutaneous syndrome, occurring once in every 3000 births. The clinical manifestations vary widely, and the condition may not be apparent in infancy. Additional stigmata may appear as the patient ages. The disorder is secondary to a defect in the gene neurofibromin (on chromosome 17). NF1 is inherited in an autosomal-dominant pattern. In approximately half the patients with NF1, a parent is similarly affected. In those with no family history of NF1, it is assumed that the patient’s disease is the result of a spontaneous mutation; the disorder is then passed along to the patient’s progeny in an autosomal-dominant manner.

A diagnosis of NF1 in children relies on fulfillment of at least two of the following seven clinical criteria:

1. Six or more café au lait macules >5 mm in diameter (prepubertal) or >1 cm in diameter (postpubertal) (Fig. 35.1)

2. Two or more neurofibromas of any type, or one plexiform neurofibroma

3. Freckling in the axillary or inguinal region (see Fig. 35.1)

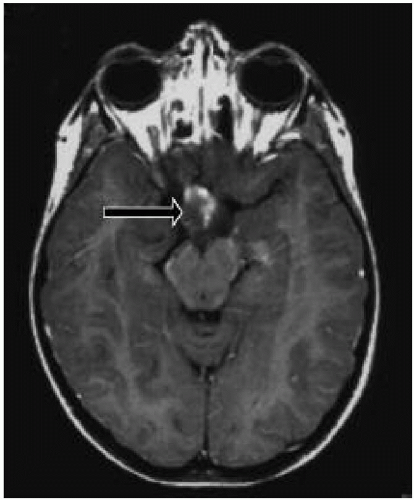

4. Presence of an optic glioma (Fig. 35.2)

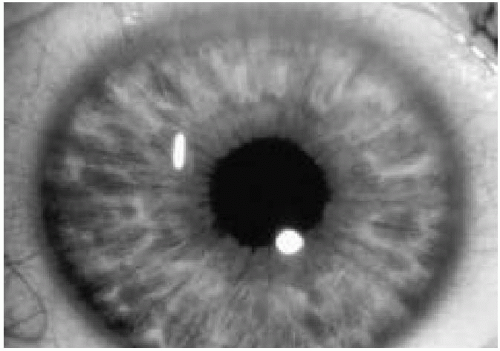

5. Two or more Lisch nodules (Fig. 35.3)

6. A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or pseudoarthrosis

7. A first-degree relative diagnosed with NF1 on the basis of the preceding criteria

Café au lait spots are the most common clinical finding in children with NF1 (see Fig. 35.1). They are usually recognized in the first year of life and appear to “increase” in number, size, and darkness with age. The borders are generally smooth, and detection is enhanced by using a Wood’s lamp. No correlation has been found between the number of spots and the severity of the disorder. Patients

with NF1 may have axillary and inguinal freckling (see Fig. 35.1) and areas of hyperpigmentation over the plexiform neurofibromas.

with NF1 may have axillary and inguinal freckling (see Fig. 35.1) and areas of hyperpigmentation over the plexiform neurofibromas.

Figure 35.1 Café au lait macules and axillary freckling in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. (See color insert.) |

Neurofibromas may develop on any nerve at any location in the body, externally or internally. Cutaneous neurofibromas are rare in infancy but become more common after puberty. Some patients have very few lesions, whereas others have hundreds of them. Neurofibromas rarely transform into neurofibrosarcomas. Plexiform neurofibromas are larger, soft, spongiform masses that may be congenital, may enlarge, and may cause cosmetic and functional problems.

Lisch nodules are pigmented hamartomas of the iris (see Fig. 35.3) that usually appear after school age. They are not a threat to vision. A slit-lamp examination is necessary to identify them. The incidence of optic nerve gliomas in patients with NF1 is 5% to 10%; they usually resorb over time, but may progress and require close follow-up.

The skeletal manifestations of NF1 include scoliosis, kyphosis, short stature, pseudoarthrosis, and pectus excavatum. Infants should be examined for pseudoarthrosis, and children entering adolescence should be closely observed for kyphoscoliosis.

The neurologic aspects of NF1 may include macrocephaly, hydrocephalus, skull defects, central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system tumors, mental retardation, learning disabilities, and epilepsy.

Patients with NF1 may also have vascular disorders. Renal artery stenosis with aneurysm formation may cause hypertension and pheochromocytoma, and cerebrovascular lesions may result in hemorrhage and stroke.

If a child is suspected of having NF1, a complete physical examination, including blood pressure measurement, formal funduscopic examination, and an assessment of visual acuity and visual fields, should be undertaken. Cutaneous lesions should be recorded. If cutaneous lesions enlarge rapidly, become painful, or develop in an

area that causes discomfort, such as the foot or waistline, the patient should be referred for removal of the lesions. If diminished visual acuity or a visual field cut is noted, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with orbital views performed with and without contrast is indicated. Many children have benign macrocephaly. Patients should be followed up yearly, and they and their parents should be questioned concerning development or change in any of the neurologic symptoms. Because the incidence of learning disabilities in children with NF1 is very high (35%), early intervention should be considered in an effort to identify and remediate any learning difficulties.

area that causes discomfort, such as the foot or waistline, the patient should be referred for removal of the lesions. If diminished visual acuity or a visual field cut is noted, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with orbital views performed with and without contrast is indicated. Many children have benign macrocephaly. Patients should be followed up yearly, and they and their parents should be questioned concerning development or change in any of the neurologic symptoms. Because the incidence of learning disabilities in children with NF1 is very high (35%), early intervention should be considered in an effort to identify and remediate any learning difficulties.

Figure 35.3 Pigmented hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules) in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. (See color insert.) |

Genetic counseling is necessary in all instances. When NF1 is identified in a child, the parents should undergo a cutaneous examination and a slit-lamp examination. If NF1 is recognized in either of them, that parent should be followed up yearly. As the pediatric patient reaches maturity and enters the reproductive years, genetic counseling is again indicated. DNA testing for NF1 is not 100% sensitive, and therefore is not routinely utilized.

Neurofibromatosis Type 2

Frequency: 1/35,000

Inheritance: autosomal dominant

Features: late onset (approximately 22 years), acoustic neuromas (cranial nerve [CN] VIII), schwannomas, gliomas, meningiomas, neurofibromas, cataracts, and few café au lait spots

Complications: hearing loss, tinnitus, and visual loss

Primary defect: schwannomin (a.k.a. merlin) gene on chromosome 22

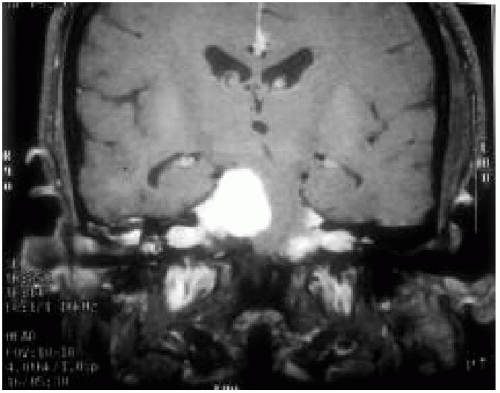

NF2, initially thought to be the “central” form of NF1, is now recognized as a separate disorder. It is secondary to an abnormality in the schwannomin gene (on chromosome 22). Patients usually present in early to middle adult life with hearing loss, at which time bilateral acoustic neuromas are identified (Fig. 35.4). Their children should undergo a thorough examination, including MRI of the head and spine and auditory evoked potentials. NF2 is more aggressive if presenting in childhood, and most pediatric patients have acoustic neuromas and spinal cord tumors at the initial evaluation. Patients with NF2 must be evaluated and followed up by a geneticist, and they require the lifelong services of neurologists, otologists, and neurosurgeons.

The diagnostic criteria for NF2 (only one criterion is required):

Bilateral CN VIII mass on MRI with gadolinium

Positive family history (parent, child, or sibling)

and either unilateral CN VIII mass or one of the following:

Neurofibroma

Meningioma

Glioma

Schwannoma

Posterior capsular cataract (at young age)

Tuberous Sclerosis

Frequency: 1/25,000

Inheritance: autosomal dominant

Features: ash leaf spots, shagreen patches, café au lait spots, adenoma sebaceum, subungual fibromas; epilepsy, mental retardation, intracranial calcifications; cardiac rhabdomyoma; renal anomalies

Primary defect: tuberin (chromosome 16), or hamartin (chromosome 9) mutations

TS is an autosomal-dominant condition that occurs in 1 in 25,000 live births; however, the spontaneous mutation rate is 60% to 70%. The disorder is caused by an abnormality in either the hamartin gene (on chromosome 9) or the tuberin gene (on chromosome 16). Characteristic manifestations include skin abnormalities, epilepsy, and mental retardation. Roach and Sparagana (2004) suggested that the features of this disorder can be classified as major or minor. The major features include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree