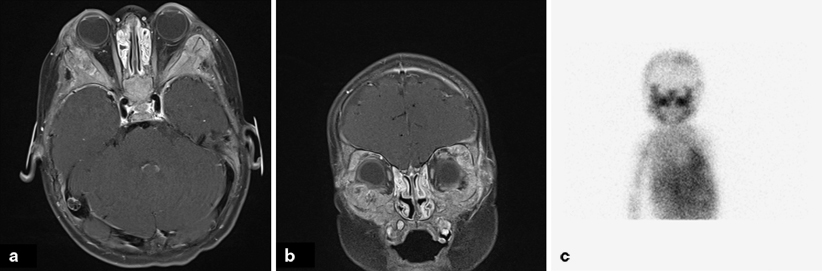

Fig. 31.1

MRI of a 4-month-old infant who presented with right Horner syndrome. T1 coronal (a) and T2 axial (b) images show a mass within the carotid space. Biopsy showed neuroblastoma

Bone is the most frequent site of metastasis in patients with NB, with the posteriolateral part of the bony orbits being one of the most frequent sites of clinical presentation. (Fig. 31.2) With bony or soft tissue metastasis around the eye, proptosis can occur. “Raccoon eyes,” a dramatic presentation of the disease, is a result of metastatic hemorrhagic tumor in orbital bone and soft tissue.

Fig. 31.2

Metastatic neuroblastoma. a Axial T1 MRI image showing diffuse expansile marrow infiltration involving the bilateral craniofacial bones. b Coronal T1 MRI image showing diffuse involvement of the orbital bones. c I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan showing uptake in the involved structures

Respiratory and Gastrointestinal Issues

Respiratory distress due to trachea compression can occur with large masses or masses that arise in the retropharyngeal space.

Difficulty swallowing and vocal cord paralysis have also been reported [21].

Differential Diagnosis

Most patients will present with a mass; thus the differential diagnosis includes mostly a variety of neoplastic and few nonneoplastic conditions (Table 31.1).

Table 31.1

Differential diagnosis of neuroblastoma

Primary site | Differential diagnosis |

|---|---|

Abdomen | Wilms tumor |

Hepatoblastoma | |

Rhabdomyosarcoma | |

Lymphoma | |

Thorax and retroperitoneum | Lymphoma |

Germ cell tumor | |

Neck | Lymphoma |

Infection | |

Bone | Lymphoma |

Rhabdomyosarcoma | |

Soft tissue sarcomas | |

Langerhans cell histiocytosis | |

Bone marrow | Lymphoma |

Leukemia (especially megakaryoblastic leukemia) | |

Spinal canal | Desmoid tumor |

Epidermoid tumor | |

Teratoma | |

Astrocytoma | |

Skin | Dermoid cysts |

Subcutaneous fat necrosis | |

Infantile fibrosarcoma | |

Rhabdomyosarcoma | |

Congenital leukemia |

Diagnosis and Evaluation

Physical Examination

Physical examination should include a detailed head and neck evaluation looking for fixed, hard cervical masses as well as common ocular presentations of the disease, including Horner’s syndrome, opsoclonus, proptosis, and periorbital ecchymoses. Skull based metastatic lesions may also be palpable. The abdominal exam should aim to assess for the presence of hepatomegaly and/or a fixed, hard abdominal mass, as primary tumors arising from the adrenal gland are most common. Lastly, a detailed neurologic exam specifically looking for an evolving paralysis is essential in all patients with NB until paraspinal masses have been ruled out.

Laboratory Data

Urinary catecholamine metabolites 4-hydroxy-3-methoxymandelic acid (VMA) and homovanillic acid (HVA) are elevated in greater than 90 % of patients with NB.

Standard preoperative laboratory studies (complete blood count (CBC) with differential, clotting times (PT/PTT), type and cross (T&C) for blood bank, chemistry panel (Chem 10)).

Imaging Evaluation

Evaluation of the head and neck usually should include an MRI for better evaluation of extent of disease and compromise of vital structures (Figs. 31.1 and 31.2).

As most cases of NB have a primary lesion in the abdomen either arising from the adrenal gland or somewhere along the sympathetic chain, CT and/or MRI will likely be needed to assess tumor burden in the abdomen.

Chest radiograph (Posterior Anterior and lateral) is needed to assess for thoracic disease. If positive, CT of the chest should follow.

Evaluation of the bony skeleton is necessary to assess for metatstatic lesions. I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG), an agent that concentrates in cells that receive sympathetic innervation, is taken up by 90 % of NBs. As a result, MIBG scans are more sensitive and specific than a bone scan. The 123I MIBG scan is thought to be a better diagnostic tool than the 131I MIBG scan [22]. Most institutions will perform a bone scan and 123I MIBG scan at presentation, but will then limit to 123I MIBG scan if the scans are concordant (Fig. 31.2).

Pathology

The International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification (INPC), established in 1999 and later revised in 2003, uses morphologic features including Schwannian stroma development, grade of neuroblastic differentiation, and mitosis-karyorrhexis index (MKI) to determine if neuroblastic tumors are of favorable or unfavorable histology (Table 31.2) [23, 24]. The INPC includes age at diagnosis as well, but the morphologic features alone have been found to be prognostic independent of age [25].

Table 31.2

International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification. (Shimada index)

Schwannian stroma | Age (years) | Grade of neuroblastic differentiation | MKI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Favorable | ≥ 50 % | All | GN of GNB, non-nodular | |

< 50 % | 1.5–5 | Differentiated | MKI < 100 | |

< 50 % | < 1.5 | MKI < 200 | ||

Unfavorable | ≥ 50 % | All | Nodular | |

< 50 % | > 5 | |||

< 50 % | 1.5–5 | Undifferentiated | ||

< 50 % | < 1.5 | MKI < 200 |

Undifferentiated and poorly differentiated NB are the most immature and aggressive of the neuroblastic tumors with no significant Schwannian stroma and composed of neuroblasts without or with neuropil, respectively (Fig. 31.3a). MKI can vary throughout the tumor cells. NB is one of the many small round blue cell tumors of childhood and when devoid of neuropil can be difficult to distinguish from other small round blue cell tumors such as lymphoma, osteosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Ewing Sarcoma. Immunohistochemistry using antibodies that specifically interact with neural tissue such as synaptophysin and chromogranin, is often positive in NB. Ganglionic differentiation as well as the presence of significant Schwannian stroma in neuroblastic tumors are important in the histopathologic classification. In differentiating NB, more than 5 % of tumor cells show ganglionic differentiation (Fig. 31.3b). Ganglioneuroma is benign and composed entirely of mature ganglion cells (Fig. 31.3c; a variant of ganglioneuroma, the maturing ganglioneuroma is also benign but some ganglion cells are small and not fully developed). Ganglioneuroblastomas are composite tumors made of NB and ganglioneuroma . There are two variants: the intermixed ganglioneuroblastoma in which poorly differentiated neuroblasts are dispersed within the ganglioneuroma and the nodular ganglioneuroblastoma in which the NB component form separate grossly visible nodules.

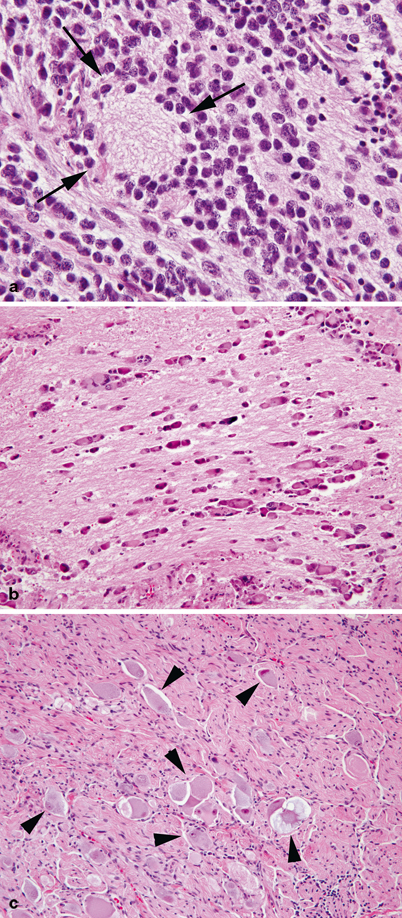

Fig. 31.3

a Poorly differentiated neuroblastoma. Round blue cells are immersed in a fibrillary background rich in neuropil. A characteristic rosette centered around neuropil is indicated by arrows. b Differentiating neuroblastoma. Ganglionic differentiation is present in most of the tumor cells, which are separated by abundant neuropil. c Ganglioneuroma. Tumor composed of numerous mature ganglion cells (arrowheads) and a bland neurofibroma-like stroma are shown.

Pathologic review of the bone marrow aspirate and biopsy from bilateral iliac crests as well as the primary mass should be performed in the evaluation of NB. Approximately ten core needle biopsies of the mass should be obtained for histopathologic diagnosis.

Treatment

Surgical Therapy

Current International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) pretreatment risk stratification takes into account disease stage, patient age, histopathology classification, MYCN amplification status, ploidy and allelic loss of heterozygosity at 1p or 11q. It is this risk stratification that determines the next steps in NB treatment (Table 31.3) [26].

INRG stage | Age (months) | Histological category | Grade of tumor differentiation | MYCN | 11q aberration | Ploidy | Pretreatment risk group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

L1/L2 | GN maturing; GNB intermixed | Very low | |||||

L1 | Any, except GN maturing or GNB intermixed | NA | Very low | ||||

Amp

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|