Benign conditions

Infectious mononucleosis

Atypical mycobacterial and other lymphadenitis

Juvenile angiofibroma

Malignant conditions

NUT (nuclear protein in testis) midline carcinoma

Sinonasal carcinoma

Parameningeal rhabdomyosarcoma

Esthesioneuroblastoma

Lymphoma

Cervical neuroblastoma

Nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma

An important entity recently described, which should be included in the differential diagnosis of nasopharyngeal malignancies presenting with aggressive behavior and rapid progression, is NUT (nuclear protein in testis) midline carcinoma. This is a very rare and aggressive malignancy genetically defined by rearrangements of the gene, NUT. In the majority (75 %) of cases, the NUT gene on chromosome 15q14 is fused with BRD4 on chromosome 19p13, creating chimeric genes that encode the BRD-NUT fusion proteins. In the remaining cases, NUT is fused to BRD3 on chromosome 9q34 or an unknown partner gene; these tumors are termed NUT-variant [16]. The tumors arise in midline epithelial structures, typically mediastinum and upper aerodigestive tract, and present as very aggressive undifferentiated carcinomas, with or without squamous differentiation [17]. Although the original description of this neoplasm was made in children and young adults, patients of all ages can be affected. The outcome is very poor, with an average chance of survival of less than 1 year. Preliminary data seem to indicate that NUT-variant tumors may have a more protracted course [17]. Preclinical studies have shown that NUT-BRD4 is associated with globally decreased histone acetylation and transcriptional repression and that this acetylation can be restored with histone deacetylase inhibitors, resulting in squamous differentiation, arrested growth in vitro, and growth inhibition in xenograft models. Response to vorinostat has been reported in a case of a child with refractory disease, thus suggesting a potential role for this class of agents in the treatment of this malignancy [18].

Diagnosis and Evaluation

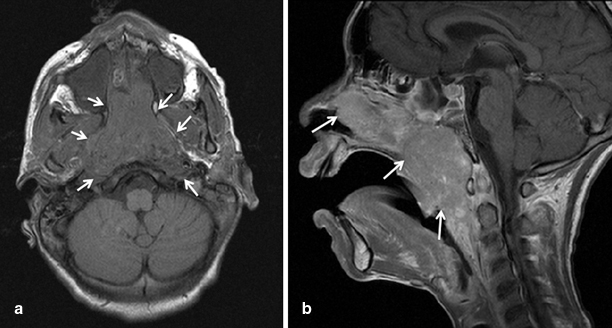

NPC should always be suspected in an adolescent presenting with nasal congestion or epistaxis, headache, and a cervical mass. Most patients present with bilateral cervical metastases, and an asymptomatic cervical disease may be the presenting sign. Nasal endoscopy usually shows a nasopharyngeal mass, and a biopsy of the primary tumor is always recommended; however, a diagnosis can also be made with a biopsy of a cervical lymph node in the context of a suggestive nasopharyngeal mass. Imaging studies should include proper locoregional imaging and evaluation of metastatic sites. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck, extending to the supraclavicular fossa, is recommended, and a computed tomography (CT) may be performed to better define skull base erosion (Fig. 30.1). A CT scan of the chest is also recommended to evaluate the presence of parenchymal metastases as well as mediastinal nodal disease, which usually develops as an extension of the cervical metastases. While the role of a positron emission tomography (PET) scan is not clear at the time of diagnosis, it may facilitate the evaluation of response to therapy [19].

Fig. 30.1

Axial (a), and sagital (b) MRI images showing a large nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a 14-year-old African-American male patient

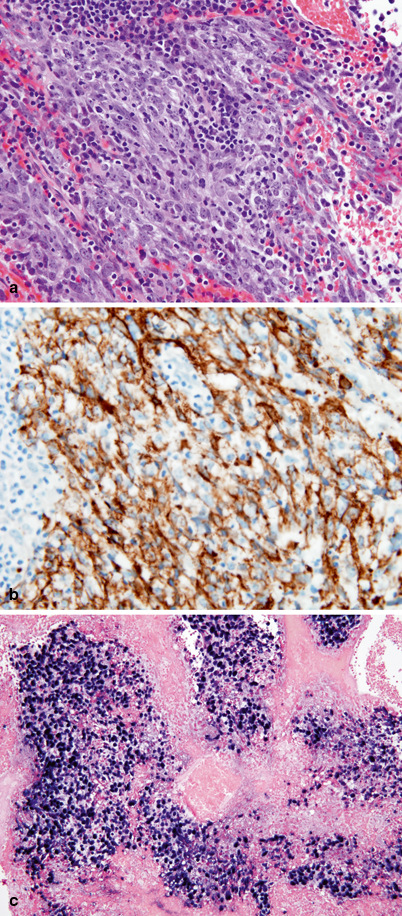

The keratinizing NPCs are conventional squamous cell carcinomas with readily seen keratinization and desmoplastic reaction. The nonkeratinizing carcinomas show minimal or absent keratinization mimicking urothelial transitional cell carcinomas. The undifferentiated type of NPC is the most frequent type seen in the pediatric age group. In this type, the neoplastic cells may have a diffuse, noncohesive growth pattern mimicking a lymphoma or may have a syncytial cohesive growth, forming nests. Characteristically, they lack keratinization. These tumors are associated with a prominent nonneoplastic lymphoid component. By immunohistochemistry, all types of NPC are immunoreactive with cytokeratin. EBV EBER in situ hybridization is positive in all undifferentiated NPCs and 100 % of the neoplastic cells contain the virus (Fig. 30.2).

Fig. 30.2

a Undifferentiated type nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) showing a large group of cohesive neoplastic cells with amphophilic cytoplasm and oval nuclei with single prominent eosinophilic nucleoli. Numerous, interspersed inflammatory cells (predominantly lymphocytes) are also present. b Tumor cells are strongly and diffusely immunoreactive for pancytokeratin AE1AE3. c EBV EBER in situ hybridization showing positive staining (dark blue) in the nuclei of all tumor cells

Staging of NPC usually follows the TNM system, which has shown to be predictive of outcome and very helpful in defining therapy (Table 30.2) [20].

Table 30.2

AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) staging system for nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Value | Definition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

T1 | Tumor confined to the nasopharynx, or tumor extends to oropharynx and/or nasal cavity without parapharyngeal extension | ||

T2 | Tumor with parapharyngeal extension | ||

T3 | Tumor invades bony structures of skull base and/or paranasal sinuses | ||

T4 | Tumor with intracranial extension and/or involvement of cranial nerves, hypopharynx, orbit, or with extension to the infratemporal fossa/masticator space. | ||

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | ||

N1 | Unilateral metastasis in cervical lymph node(s), ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension, above the supraclavicular fossa, and/or unilateral or bilateral, retropharyngeal lymph nodes, ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension | ||

N2 | Bilateral metastasis in cervical lymph node(s), ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension, above the supraclavicular fossa | ||

N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node(s)c> 6 cm and/or to supraclavicular fossa | ||

N3a: > 6 cm in dimension | |||

N3b: Extension to the supraclavicular fossa | |||

M0 | No distant metastasis | ||

M1 | Distant metastasis | ||

Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIA | T2a | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIB | T1 | N1 | M0 |

T2 | N0 | M0 | |

T2 | N1 | M0 | |

Stage III | T1 | N2 | M0 |

T2 | N2 | M0 | |

T3 | N0-2 | M0 | |

Stage IVA | T4 | N0-2 | M0 |

Stage IVB | Any T | N3 | M0 |

Stage IVC | Any T | Any N | M1 |

Treatment

NPC is considered to be unresectable due to the complex anatomical location. NPC is a very radiosensitive tumor, and radiation therapy is considered to be the primary treatment modality. High doses (> 65 Gy) are usually required to achieve good locoregional control [13−15, 21, 22]. The regional lymph nodes in the entire head and neck area are irradiated, and the structures surrounding the nasopharynx and entire neck should be also included in the treatment. The disease control rates with radiation therapy are stage dependent, with survival rates of 65–85 % for patients with stage II and of less than 50 % for patients with stage IV disease [23]. The development of both locoregional and distant recurrence correlates with the size of the primary tumor and the nodal staging. Tumors of undifferentiated histology (World Health Organisation (WHO) type III) are more radiosensitive, and this correlates with better outcome [21].

Despite the progress in the delivery of radiation therapy and supportive care, a significant proportion of patients with locoregionally advanced disease fail treatment, and long-term survival rates are unsatisfactory. Unlike other head and neck cancers NPC is a very chemosensitive neoplasm, and the use of chemotherapy might thus provide benefit for patients with advanced disease. Among the drugs tested those with best single-agent activity include methotrexate, bleomycin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), cisplatin (CDDP), and carboplatin [13−15, 22]. The response rates in combination studies range from 38–91 %, with CDDP-containing regimens showing clear advantage over non-CDDP containing regimens. Most of the information on the role of chemotherapy derives from studies performed in adult NPC [24]. Chemotherapy has been administered in the neoadjuvant, concurrent, and adjuvant settings. Considering the chemosensitivity of NPC, the administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy has the advantage of inducing an immediate response and symptom alleviation, while allowing for more time for radiation planning. Cisplatin may enhance radiation toxicity by inhibiting the repair of sublethal damage, reoxygenation and recruitment of cells into a proliferative state, and radiosensitization of hypoxic cells [25]. Thus, the administration of cisplatin during radiation therapy (concurrent chemoradiation) has a strong rationale, and randomized studies have shown a survival advantage when compared with radiation alone [24]. Administration of chemotherapy after radiation therapy has also been explored; however, this sequence seems to be much less tolerable, and compliance is lower [24]. In a meta-analysis evaluating randomized clinical trials that explored the role of neoadjuvant, concurrent, and adjuvant chemotherapy for NPC, the greatest survival advantage was associated with the use of concurrent chemoradiation, with a survival benefit of 20 % . Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was also associated with improved survival, as result of a decrease in distant and local relapses [24]. Administration of chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting does not seem to be associated with any significant benefit, and was shown to be associated with more toxicity and lower compliance rates [24, 26]. Few studies have evaluated the impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemotherapy, but this seems to be an approach associated with reasonable toxicity and good outcomes in adult NPC [27].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree