Chapter 521 Nephrotic Syndrome

Etiology

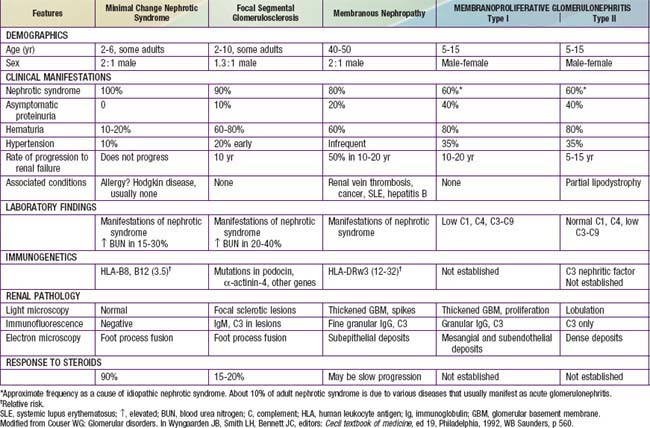

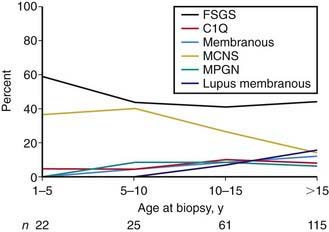

Most children with nephrotic syndrome have a form of primary or idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (Table 521-1). Glomerular lesions associated with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome include minimal change disease (the most common), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, membranous nephropathy and diffuse mesangial proliferation (Table 521-2). These etiologies have different age distributions (Fig. 521-1).

Table 521-1 CAUSES OF CHILDHOOD NEPHROTIC SYNDROME

GENETIC DISORDERS

Nephrotic Syndrome (Typical)

Proteinuria with or Without Nephrotic Syndrome

Multisystem Syndromes with or Without Nephrotic Syndrome

Metabolic Disorders with or Without Nephrotic Syndrome

IDIOPATHIC NEPHROTIC SYNDROME

SECONDARY CAUSES

Infections

Drugs

Immunologic or Allergic Disorders

Associated with Malignant Disease

Glomerular Hyperfiltration

Note: Childhood nephrotic syndrome can also be consequence of inflammatory glomerular disorders, normally associated with features of nephritis, e.g., vasculitis, lupus nephritis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy.

From Eddy AA, Symons JM: Nephrotic syndrome in childhood, Lancet 362:629–638, 2003.

Nephrotic syndrome may also be secondary to systemic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, malignancy (lymphoma and leukemia), and infections (hepatitis, HIV, and malaria) (see Table 521-1).

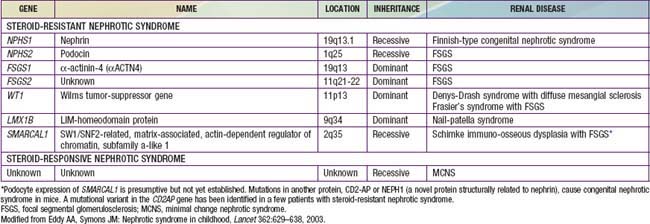

A number of hereditary proteinuria syndromes are caused by mutations in genes that encode critical protein components of the glomerular filtration apparatus (Table 521-3).

Pathophysiology

The underlying abnormality in nephrotic syndrome is an increased permeability of the glomerular capillary wall, which leads to massive proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia. On biopsy, the extensive effacement of podocyte foot processes (the hallmark of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome) suggests a pivotal role for the podocyte. Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome is associated with complex disturbances in the immune system, especially T cell–mediated immunity. In focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, a plasma factor, probably produced by a subset of activated lymphocytes, may be responsible for the increase in capillary wall permeability. Alternatively, mutations in podocyte proteins (podocin, α-actinin 4) and MYH9 (podocyte gene) are associated with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (see Table 521-3). Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome can be associated with mutations in NPHS2 (podocin) and WT1 genes, as well as other components of the glomerular filtration apparatus, such as the slit pore, and include nephrin, NEPH1, and CD-2 associated protein.

Del Rio M, Kaskel F. Evaluation and management of steroid-unresponsive nephrotic syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:163-170.

Hodson EM, Alexander SM. Evaluation and management of steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:145-150.

Liapis H. Molecular pathology of nephrotic syndrome in childhood: a contemporary approach to diagnosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2008;11:154-163.

1978 Nephrotic syndrome in children: Prediction of histopathology from clinical and laboratory characteristics at time of diagnosis. A report of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. Kidney Int. 1978;13:159.

Tryggvason K, Patrakka J, Wartiovaara J. Hereditary proteinuria syndromes and mechanisms of proteinuria. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1387-1399.

Van de Walle JGJ, Donckerwolcke RA. Pathogenesis of edema formation in the nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2001;16:283.

521.1 Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome

Pathology

In focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), glomeruli show lesions that are both focal (present only in a proportion of glomeruli) and segmental (localized to ≥1 intraglomerular tufts). The lesions consist of mesangial cell proliferation segmental scarring on light microscopy (Fig. 521-2 and see Table 521-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree