13 Nephrology

Urinary Screening and Urinalysis

Gross Inspection

On gross inspection, the color of urine may be described as clear, yellow, dark yellow, green, brown, tea colored, pink, clear red, grossly bloody, blue, or even black. Smoky, brown, or tea-colored urine is indicative of stagnated blood that has decomposed; the iron component has oxidized in the renal tubules. This commonly occurs in glomerulonephritis. Trauma, kidney stones, urinary tract infections, and strenuous exercise frequently result in frank hematuria. In the absence of hematuria on dipstick screening, numerous natural chromogens and vitamins found in foods, dyes, or medications may alter the normal yellow-amber color of urine imparted by the hemoglobin breakdown product urochrome (Table 13-1).

Table 13-1 Causes of Urine Color Alteration without Presence of Red Blood Cells

1 “Red diaper syndrome.” This is typically the result of a benign condition such as uric acid supersaturation or overgrowth of Serratia marcescens.

2 “Black diapers or undergarments.” In this disorder, yellow to dark urine becomes black to brown on exposure to air. This condition is also known as alkaptonuria and results from a defect in the enzyme homogentisate 1, 2-dioxygenase, which degrades tyrosine, leading to tissue accumulation and high urinary excretion of the tyrosine byproduct homogentisic acid.

3 “Blue diaper syndrome.” This occurs in Hartnup disease (neutral aminoaciduria) and is also seen in tryptophan gastrointestinal malabsorption syndrome, in which indigotin or indigo blue is excreted in the urine.

Microscopic Examination

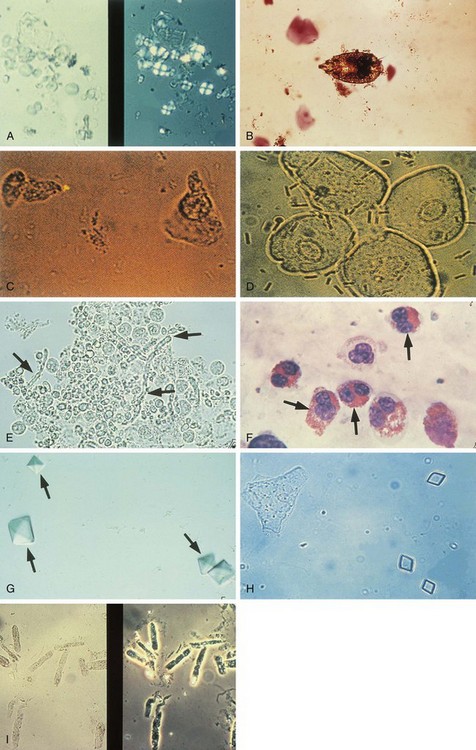

Meticulous examination of the urine sediment begins with centrifugation of 10 mL of freshly voided urine for 5 to 7 minutes at 3000 rpm. Such standardized preparation enables semiquantitative comparison of sequential samples in individual patients and often provides invaluable information concerning the etiology of numerous renal disorders as well as the anatomic location of hematuria or pyuria. Abnormalities commonly encountered on microscopy are shown in Figure 13-1. Dysmorphic RBCs, best seen in uncentrifuged urine by phase microscopy, are usually of glomerular origin as opposed to urologic origin. White blood cells (WBCs) coated with antibody tend to become agglutinated or clumped. Such clumped WBCs are indicative of pyelonephritis or interstitial nephritis rather than cystitis. The presence of several tubular epithelial cells is abnormal.

Hematuria

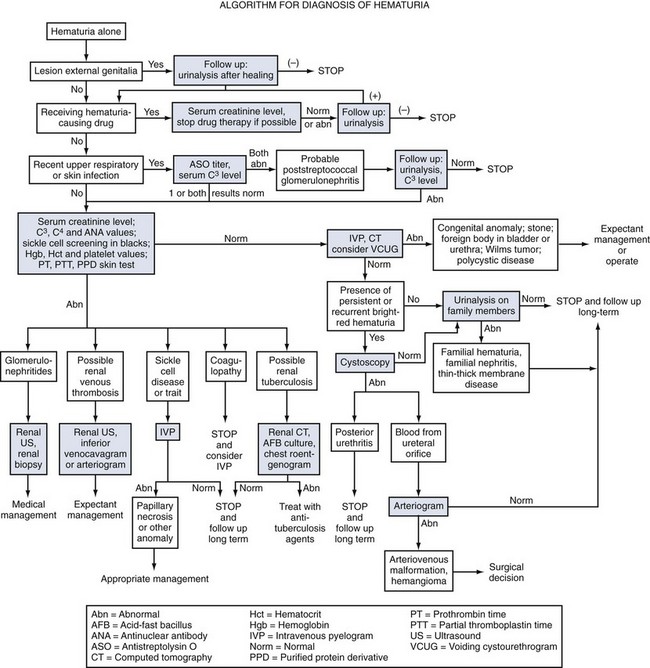

Isolated gross or microscopic hematuria is probably the most common symptom prompting nephrologic assessment in children. Many such children have asymptomatic microscopic hematuria often detected during routine office visits or physical examinations required before participation in sport activities. Because of the large number of conditions associated with persistent hematuria in children, several algorithms have been devised to aid in the systematic evaluation of this condition (Fig. 13-2).

Figure 13-2 Algorithm for diagnosis of hematuria.

(From Brewer ED, Benson GS: Hematuria: algorithms for diagnosis, JAMA 246:877-880, 1981. Copyright 1981, American Medical Association.)

Glomerular Disorders

Nephritis and Nephrosis

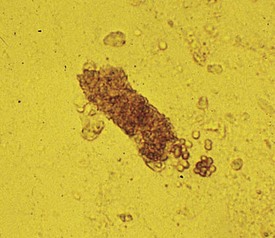

In children suspected of having a glomerular disease, the urinary sediment can provide important clues that may expedite the diagnosis and help formulate therapeutic plans. A classic example of nephritic syndrome is that of acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis, in which the urinalysis reveals variable levels of proteinuria; and granular, red (Fig. 13-3) and, less frequently, white (Fig. 13-4) blood cell casts. Acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis is the most common and classic example of postinfectious glomerulonephritis, although other preceding infections can cause glomerulonephritis. On the other hand, the urine of children with classic nephrotic syndrome, such as minimal change disease, shows heavy proteinuria (>40 mg/m2/hour or 1000 mg/m2/day), free fat droplets and oval fat bodies, and little or no hematuria or other sediment abnormalities.

Acute Glomerulonephritis

A typical presentation is that of a child 3 to 10 years of age, whose symptoms during the preceding few days have included mild periorbital edema, headache, and decreasing urine output. The urine is described as being smoky or tea colored. Medical history reveals that 2 weeks earlier the child experienced a febrile illness with painful pharyngitis for which he received no medical attention. Clinical examination reveals a blood pressure of 140/105 mm Hg, mild periorbital edema, and tenderness on palpation of the kidneys. A urinalysis shows the following values: 2+ protein, 3+ blood, and an SG of 1.020. Red blood cell casts (see Fig. 13-3) are seen on urinalysis. Laboratory studies are consistent with mild renal insufficiency and also revealed a protein excretion rate of 1.1 g/24 hours, a low plasma C3 level, and elevated streptozyme and anti-DNase B titers, evidence that strongly implicates a streptococcal infection in the pathogenesis of the glomerulonephritis.

Chronic Glomerulonephritis

White blood cell casts may be seen in the urine sediment of patients with acute or chronic glomerulonephritis, vasculitis, pyelonephritis, and other disorders resulting in tubulointerstitial nephritis. The cast shown in Figure 13-4 occurred in a child with systemic lupus erythematosus whose only symptom was mild back pain. Urinalysis demonstrated 2+ protein, microhematuria, pyuria without bacteria, and red and white blood cell casts. Diagnosis was confirmed by immunologic findings including low serum C3 and C4 levels, high anti-nuclear antibody titer, and antibodies against double-stranded DNA. Renal biopsy revealed diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. Several acute glomerular syndromes may progress to chronic glomerulonephritis. In the final stages, many such patients develop hypertension and severe renal failure (uremia). On renal ultrasonography, the kidneys appear small and hyperechoic due to fibrosis.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

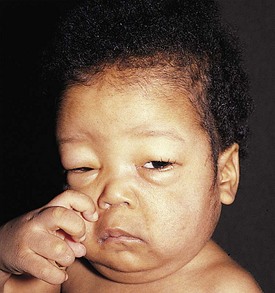

Three weeks after a respiratory infection, a 2-year-old boy experienced symptoms of generalized malaise, abdominal pain, periorbital edema, and difficulty walking “as if his legs were hurting.” One day later he developed an ecchymotic, purpuric rash, the characteristic clinical manifestation of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). The rash covered the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the buttocks but spared the trunk. Individual lesions faded over 1 week, but new lesions appeared or recurred over several weeks. Other cutaneous manifestations of the vasculitic lesions in this disorder are shown in Figures 13-5 and 13-6.

Nephrotic Syndrome

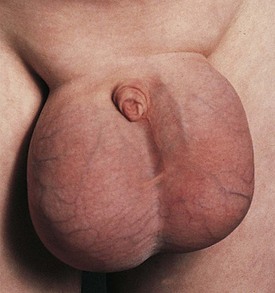

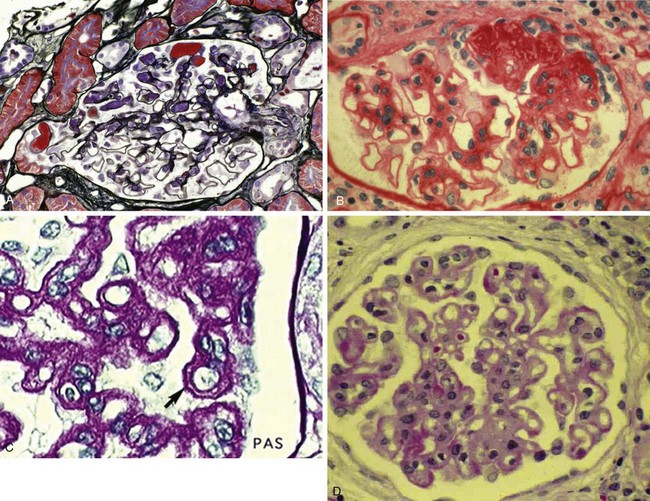

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is defined as any renal disorder resulting in marked proteinuria (≥40 mg/m2/hour, ≥1000 mg/m2/day, or spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio > 2.0), leading to hypoalbuminemia, hypercholesterolemia, and edema. Generalized edema and rapid weight gain are characteristic features of this condition, with the former showing a predilection for the eyelids, pleural spaces, abdomen, scrotum, and lower extremities (Figs. 13-7 and 13-8). Although edema usually provokes few complaints, at times it may be disfiguring, and it may produce skin induration and breakdown, or interference with respiratory, genitourinary, or gastrointestinal function. Children with NS rarely have an underlying systemic illness or a history of drug intake and thus are designated as having primary or idiopathic NS. The most common histopathologic entities of noninflammatory glomerular disorders associated with primary NS of childhood include minimal change disease (MCD), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN); membranous glomerulopathy (MGP) is also encountered in older children and in adults. Examples of the pathology of these disorders are depicted in Figure 13-9, A-D.

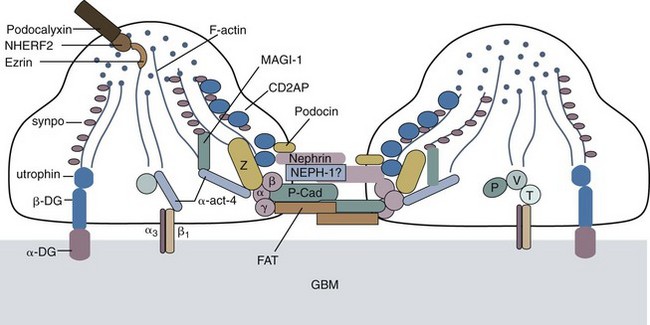

Although genetic mutations of laminin B2 and B3 chain genes and other structural proteins of the glomerular basement membrane can lead to NS, genetic mutations leading to derangements in transcription of several proteins that maintain the structure and function of the slit diaphragm of podocytes are much more common and underscore the importance of this structure as the main barrier to proteinuria (Fig. 13-10). The Finnish-type congenital NS is the prototype of a genetic mutation of nephrin and accounts for 6.25% of children with SRNS. Podocin mutations account for most familial cases of FSGS and of steroid-resistant cases (18%), especially among African-American children. Actinin IV mutations are autosomal dominant and cause a cytoplasmic defect in the podocytes (not in the slit pore diaphragm). African Americans with a form of the specific MYH9 polymorphism that encodes myosin heavy chain IIA have a much higher risk for developing FSGS in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection even during the first few months of life. This may lead to poor association of myosin and actin and disruption of the podocyte cytoskeleton.

Steroids are also useful in managing less common causes of NS such as MPGN (see Fig. 13-9, C), or steroids alternating with cyclophosphamide for 6 months in adolescents with membranous glomerulopathy (see Fig. 13-9, D).

Pediatric Nephrolithiasis

The diagnosis of nephrolithiasis should be entertained in any child with acute onset of costovertebral angle or abdominal/flank colicky pain. In younger children, renal colic is poorly localized and is often described as diffuse abdominal pain. Small stones may produce no pain and may be detected only after an episode of painless gross hematuria, pyuria, or UTI. Thus, a strong index of suspicion is required on the part of the clinician so that appropriate diagnostic studies are undertaken. Although dietary phytate is a more common cause of endemic stones in the Far East and UTI is more common in Europe, metabolic disorders predominate in children with nephrolithiasis in the United States. Relatively few children pass gravel or stones, and the kind of crystals found in the urine are rarely of diagnostic value. The clinical history and laboratory evaluation often reveal the cause of the stones. Direct chemical analysis of the calculus may also disclose the composition of the stone. One diagnostic approach to pediatric nephrolithiasis is shown in Table 13-2.

Table 13-2 Evaluation of Nephrolithiasis

| Clinical History |

Family history of nephrolithiasis Immobilization or other protracted illness or stress Excessive salt or calcium ingestion Excessive intake of vitamins or over-the-counter medications Symptoms of UTI or history of pyelonephritis Source and calcium content of drinking water Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|