Neonatology: Past, Present and Future

Gordon B. Avery

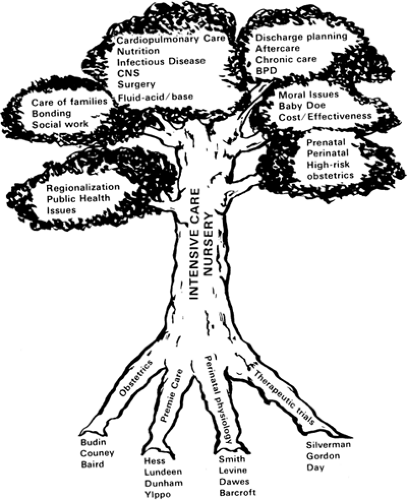

Rapid change has characterized neonatology since the name was coined in 1960 by Alexander Schaffer. Structurally, it can be compared with a tree (Fig. 1-1). Its roots—obstetrics, pediatrics, and physiology—began at the turn of the century. A sturdy trunk has developed in the intensive care nurseries (ICNs) scattered across the United States and around the world. The branches have spread so widely that it is difficult for a single person to be expert in all the areas of activity required for a tertiary neonatology service. Important interactions have gone beyond allied disciplines such as obstetrics, anesthesiology, cardiology, radiology, and surgery. Neonatologists today struggle with hospital administrators, pediatric training program directors, legislatures, Congress, the courts, the federal government, malpractice lawyers, right-to-life groups, and ethicists in an effort to determine their proper roles and limits. Caught in a cross-fire between strenuous cost-containment measures and regulations mandating the vigorous treatment of all newborns regardless of prognosis, many neonatologists wonder when a stable situation will be reached. Yet stimulating growth has occurred, mainly since 1960.

PAST: THE ROOTS

One of the main roots from which neonatology grew was supplied by obstetricians such as Pierre Budin and Sir Dugald Baird, who were interested in the babies they delivered and not merely in the immediate welfare of the mother. It may be a serious oversimplification to imply that, in former times, obstetricians were content if the baby was born alive. Childbirth, however, was the cause of a significant number of maternal deaths and for many was a fearful experience. Premature infants were expected to die, as were most neonates with malformations. There was a feeling that natural selection should be allowed to discard the “runt of the litter,” as suggested by the designation of premature babies as weaklings. It was Budin and his pupil Couney who pioneered incubator care of premature infants and thus helped change some of the early, pessimistic attitudes toward these babies.

Another significant root of neonatology can be found in the “quiet premature nursery,” such as that operated by Julius Hess and Evelyn Lundeen in Chicago in the early 1900s (1). Only premature infants were admitted to these nurseries, and gentleness with minimal intervention was the policy. To prevent infection, staff wore gowns, caps, and masks and set up a scrub routine that excluded parents and minimized traffic in the area. Feedings of breast milk by eyedropper were delayed for up to 72 hours, and the infants were handled as little as possible. Yet the supportive conditions needed to allow the body to recover, as described by Florence Nightingale, were present: “warmth, rest, diet, quiet, sanitation, space, and others” (2). Perhaps some of the high-tech nurseries of today could benefit from an infusion of this superb nurturing orientation.

Physiology is a taproot of neonatology. Advances in neonatal care rest directly on descriptions of the changing body processes of the newborn infant. Men such as Barcroft and Dawes began delineation of fetal circulation and placental function. These studies in turn led to the establishment of the fetal lamb model, which subsequently was widely exploited. Neonatal metabolic, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and central nervous system functions were studied by Levine, Smith, Peiper, and others. The 1945 publication of the first edition of Clement Smith’s textbook, The Physiology of the Newborn Infant, was a signal event in our evolving ability to care for sick newborns in a rational manner (3).

A final anchoring root of neonatology is the therapeutic trial. Innumerable traditional teachings about premature infants eventually have been proved false. Without scientific testing as a guide, neonatologists would constantly be off course. As it is, several dangerous misadventures have been averted by clinical trials. An example is prophylactic sulfonamide treatment of premature infants, which was

found to cause increased kernicterus (4). Silverman, Gordon, and Day were pioneers who insisted on rigor in such trials.

found to cause increased kernicterus (4). Silverman, Gordon, and Day were pioneers who insisted on rigor in such trials.

PRESENT: THE TRUNK

The ICN is the institution that forms the sturdy trunk of endeavors in neonatology. The ICN is a therapeutic environment, a collection of equipment, and a multidisciplinary team that is guided by dedicated leadership, by a group of specific protocols, and by a body of relevant scientific knowledge. It is the ICN as an integrated organism, rather than any single person or collection of people, that takes care of the sick neonate—in a sense, this is holistic medicine turned inside out. The ICN is very effective in the care of desperately ill babies, but its rationale remains difficult to explain to hospital administrators, insurance companies, and the U.S. Congress.

Over the years, there has been a steady increase in the intensity of illness observed in the ICN. With this rise has come an increase in the number and variety of personnel and the amount of technically sophisticated equipment. In the 1950s, premature care was a major concern. The principal interventions were resuscitation, thermoregulation, careful feeding, simple and exchange transfusion, and supportive care of respiratory distress. By the 1960s, electronic monitors came into use, and blood gases began to be measured. Feedings were aided by nasogastric tubes, and in-creased laboratory monitoring became possible. Antibiotics became available for treatment of neonatal sepsis.

By the 1970s, the use of umbilical catheters and arterial pressure transducers was routine, and respirator therapy for hyaline membrane disease began to succeed. Nutritional support for sick infants was aided by transpyloric feeding tubes and finally by complete intravenous alimentation. Microchemistry tests for most necessary parameters became widely available. Neonatal surgery was shown to be feasible for many congenital abnormalities, including serious cardiac defects. With the 1980s came the advent of computed tomography and ultrasonography. Significant concern centered around ventricular hemorrhages and consequent post hemorrhagic hydrocephalus in small premature infants. Transcutaneous electrodes became available first for measurement of oxygen and then for carbon dioxide. Pulse oximetry was used increasingly for continuous physiologic monitoring. Nutritional and metabolic supports were significantly refined. Surfactant replacement has reduced the severity of lung disease in premature infants. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation permitted the survival of some previously unsalvageable infants. In the 1990s, magnetic resonance imaging improved visualization of lesions, and positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance spectroscopy promise to reveal the physiology of the intact brain. As survival has become common for infants who weigh as little as 600 g (1.3 lb) at birth, increased attention has swung to assuring intact survival, and the 1990s have been dubbed the decade of the brain.

THE BRANCHES

Perinatology

A body of specialized knowledge, a group of subspecialized professionals, the advent of technically advanced equipment, and the formation of special care units all contributed to the development of neonatology. In obstetrics, these same elements came together approximately 10 years later and resulted in the specialty of maternofetal medicine. Perinatologists developed high-risk prenatal clinics and special delivery facilities for unstable patients. A steadily growing body of literature from animal and clinical investigations allowed improved management of pregnancy complications and monitoring of fetal status. Ultrasonography detected fetal abnormalities and determined fetal size, anatomy, activity, breathing, and response to stress. For the first time, mothers were given drugs designed to treat fetal conditions, and intrauterine transfusions were performed in cases of threatened hydrops. Fetal surgery has yet to find its proper place, but prenatal shunts have been inserted for hydrocephalus, obstructed urinary tracts have been drained, and diaphragmatic hernia repair has been attempted.

In many major teaching hospitals, perinatal obstetric and neonatal services have joined forces to form perinatal centers. Often with codirectors from the two disciplines,

these centers foster cooperation in the best interests of the high-risk patient. Integrated planning and management in optimal cases consist of a high-risk prenatal clinic, timing and management of labor and delivery, resuscitation, and intensive care in the nursery. Statistics on morbidity and mortality, reviewed in periodic joint conferences, permit constant refinement of policy and technique. These centers facilitate training programs in both perinatology and neonatology and are important sources for research. They demonstrate the best survival rates for small premature and other categories of infants at highest risk, and they provide the standard by which perinatal care is judged.

these centers foster cooperation in the best interests of the high-risk patient. Integrated planning and management in optimal cases consist of a high-risk prenatal clinic, timing and management of labor and delivery, resuscitation, and intensive care in the nursery. Statistics on morbidity and mortality, reviewed in periodic joint conferences, permit constant refinement of policy and technique. These centers facilitate training programs in both perinatology and neonatology and are important sources for research. They demonstrate the best survival rates for small premature and other categories of infants at highest risk, and they provide the standard by which perinatal care is judged.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree