Neonatal Transport

Karen S. Wood

Carl L. Bose

HISTORY

Neonatal transport began in 1900 with the development of the first mobile incubator for premature infants by Dr. Joseph DeLee of the Chicago Lying-In Hospital (1). This “hand ambulance” provided warmth while transporting premature infants to the hospital following home birth. The development acknowledged the need to create a controlled environment for the transport of infants that simulated the inpatient setting. In 1934, the first dedicated neonatal transport vehicle in the United States was donated to the Chicago Department of Health by Dr. Martin Couney (2), following the closure of the Chicago World’s Fair where the vehicle was used to transport premature babies to the exhibit. The first organized transport program in the United States began in 1948 with the development of the New York Premature Infant Transport Service by the New York Department of Health in conjunction with area hospitals (3,4). This remarkable system, created more than a decade before the evolution of neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), incorporated many of the features of modern neonatal transport programs, including around-the-clock staffing by specially trained nurses, dedicated vehicles, a clerk to receive referral calls, and equipment designed specifically for neonatal transport. During a two-year period, this program transported 1,209 patients, of whom 194 weighed less than 1,000 g (4).

Neonatal transport took to the air in 1958 with the first fixed-wing transport of a newborn infant by the Colorado Air National Guard (2). The 1967 flight of a premature baby to St. Francis Hospital in Peoria, Illinois using the Peoria Journal Star helicopter marked the first rotor-wing neonatal transport (2). Routine use of air transportation for neonatal patients began in 1972 with Flight for Life of Denver’s St. Anthony Hospital (5).

Proliferation of organized transport programs occurred in the late 1970s, in conjunction with regionalization of perinatal care. Regionalization initially minimized the number of infants requiring transport by promoting maternal-fetal transport. Regionalization also shifted the responsibility for transporting infants born in outside centers to the tertiary care center. Subsequently, the next decade saw improvements in perinatal mortality (6) and neonatal morbidity (7) as the percentage of very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants delivered in level III hospitals increased.

Since the late 1980s patterns of referral dictated by schemes of regionalization deteriorated in many areas (8), coincident with an increase in level II hospitals capable of providing some degree of neonatal intensive care. As a result, increasing numbers of infants deliver at centers without subspecialists or the necessary support services demanded by some VLBW infants. Community-based neonatal intensive care creates a need to transport infants at a critical time in their illness, occasionally while receiving therapies such as high-frequency ventilation or inhaled nitric oxide, which are not easily portable. Even in areas where regionalized perinatal care persists and prenatal risk assessment is routine, unpredictable, emergent events may precipitate the delivery of an infant in an unsuitable hospital. Collectively these situations mandate increasingly sophisticated neonatal transport systems.

ORGANIZATION AND ADMINISTRATION

Neonatal transport can be performed by either the community hospital referring the patient (one-way transport) or by the tertiary center receiving the patient (two-way transport). Two-way transport offers an economic advantage, generally more highly skilled and experienced transport personnel (9), and may result in improved survival (10,11). The American Academy of Pediatrics supports two-way transport (12), and in most perinatal regions tertiary centers have assumed this responsibility. Of note the major disadvantage of two-way transport is the time delay in getting the transport crew to the referring hospital. The remainder of this chapter discusses two-way transport exclusively.

Administrative Personnel

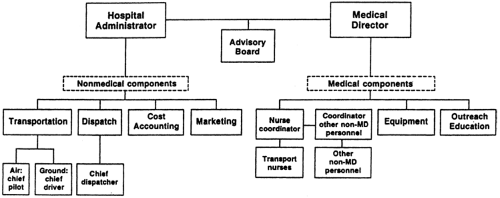

The components of a transport program include those related to medical care and the nonmedical components such as transportation, communications, finances, and

marketing. The medical components must fall under the direction of a physician who is credentialed to supervise the patients served by the program. Direction of the nonmedical components and ultimate responsibility for the program often rests with a hospital administration staff person (Fig. 4-1). The following is a brief discussion of each of the potential contributors to the administration of a transport program (13).

marketing. The medical components must fall under the direction of a physician who is credentialed to supervise the patients served by the program. Direction of the nonmedical components and ultimate responsibility for the program often rests with a hospital administration staff person (Fig. 4-1). The following is a brief discussion of each of the potential contributors to the administration of a transport program (13).

Hospital Administrator

Generally, a hospital administrator manages aspects of the program that are not directly related to patient care. Many decisions regarding program operation require a cost-benefit analysis. While medical personnel are relied on to provide an estimate of benefit, the hospital administrator must assess financial impact. Therefore, the hospital administrator should be prepared to receive advice from medical personnel and develop the nonmedical components of the program in consideration of the financial resources of the institution.

Medical Director

The medical director of a neonatal transport program is usually a neonatologist with expertise or a special interest in transport. The medical director is ultimately responsible for the quality of care provided by the transport team; this is particularly true if physicians do not participate directly in transport. The medical director assumes responsibility for developing and updating training programs, equipment procurement, and treatment protocols. The medical director, in conjunction with the coordinator of nonphysician personnel, must ensure that all personnel have completed training requirements successfully and have satisfied the regulations of the agencies that govern the various professional groups. The director also must develop and maintain a system for reviewing the quality of care provided during transport.

Coordinator of Nonphysician Personnel

Each group of professionals (e.g., nurses, respiratory therapists, paramedics) on the transport team should have a designated coordinator. The coordinator supervises the selection and training of personnel and develops systems of peer review. Additional coordinator responsibilities include scheduling personnel, organizing continuing medical education, ordering supplies and equipment, monitoring documentation standards, promoting effective internal dynamics, and identifying the needs of team members. It is advisable to designate a single person to coordinate team activities who will interface closely with the medical director and, in some programs, the hospital administrator as well.

Consulting Neonatologists and Other Subspecialists

During the transport of a patient, it is important, and often mandated by state law, that a physician provides consultation to the transport team. This physician, known as the medical control officer (MCO), is typically the physician receiving the patient and often has already discussed the patient’s care with the referring physician and made recommendations about interim management. Given this broad consultative role to both the referring physician and to the transport team, the MCO should be a person with extensive training, at a level in excess of that available in the community hospital, such as a neonatologist, a trained pediatric subspecialist, or a postdoctoral fellow. In addition, the MCO must be aware of the handicaps and hazards imposed by the transport environment and must be familiar with the operational aspects of the program.

The Advisory Board

A neonatal transport program should be considered an extension of the inpatient unit to which it delivers patients.

Therefore, the operation of the program should be reviewed periodically by representatives of all services interfacing with the inpatient unit. These representatives, comprising the advisory board, might include the following:

Therefore, the operation of the program should be reviewed periodically by representatives of all services interfacing with the inpatient unit. These representatives, comprising the advisory board, might include the following:

Medical Director of the NICU

Director of the Neonatal Division

Respiratory Therapy Administrator

Nursing Administrator

Outreach Education Coordinator

Director of Public Relations

Representatives of community hospitals involved in transport

Advice should be solicited from the advisory board about all major program changes because of the impact these changes may have on their respective services.

The Transport Team

A variety of personnel participate in the inpatient care of infants, and all should be considered candidates for caretakers during neonatal transport. These personnel include the following:

Neonatologists

Neonatal fellows

Pediatric house staff

Nurse practitioners

Transport nurses

Respiratory therapists

NICU staff nurses

Paramedics

The selection of the type of personnel used by each program is based on the unique aspects of that program; however, some general principles apply that determine the relative desirability of various professionals. As the number of transports increases, it becomes less practical to send physicians on transport. Neonatologists rarely have the time to devote to frequent transports, and reimbursement is not sufficient to justify their presence. Although participation in transport can be very educational, in high-volume programs, time spent on transport by house staff and fellows potentially competes with other aspects of training. In addition, the interest in participation and expertise may vary considerably among trainees. This is a particular problem if participation is mandated. Pediatric residents who participate in transport should be senior-level trainees under close supervision.

Most high-volume programs choose to use nonphysician personnel as attendants during transport. The use of neonatal nurse practitioners offers an attractive alternative to physician attendance (14,15). Nurse practitioners are highly skilled in neonatal stabilization and care and provide a consistency of expertise not usually encountered in other professional groups. They are licensed in most states to perform all the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures required during transport. The greatest disadvantages to the use of neonatal nurse practitioners in some regions are their scarcity and high cost. They are also rarely trained, or willing, to transport patients other than neonates.

As a cost-effective alternative to nurse practitioners, many centers train readily available NICU staff nurses to participate in transport. In addition, most states permit them to perform invasive procedures as an extension of their inpatient nursing role under guidelines and protocols approved by the Boards of Nursing. Therefore, NICU staff nurses can be trained to provide all the care required by a critically ill neonate during transport. This training often is extensive, however, because the cognitive knowledge necessary to diagnose disorders and the experience to perform invasive procedures must be mastered. This extensive training must be considered when estimating the cost of using staff nurses as compared to nurse practitioners. The requirement of training is particularly burdensome when there is a high personnel turnover rate.

Most patients transported to the NICU have either respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation or are receiving supplemental oxygen. Respiratory therapists should be considered when selecting transport personnel because of their expertise in the use and maintenance of respiratory care equipment. The therapists’ ability to adapt this equipment to the unique environment of transport can be lifesaving, particularly in circumstances when unexpected events occur. The only disadvantage of using therapists is the narrow focus of their usual training. Further education and cross-training allows their scope of practice to be expanded.

Eliminating physicians from attendance during transport can create problems that must be anticipated. For example, leadership of the team is not defined by the usual medical model in which a physician assumes this role. Designating one member of the transport team as the leader—who is accountable for communication, decision making, and documentation—solves this problem.

Advisory personnel at the tertiary center, particularly physicians, often are unwilling to endorse a patient care program that does not mandate initial evaluation by a physician. This resistance usually stems from a concern for the well-being of the patient and can be overcome by the selection and training of competent nonphysician personnel. The support and endorsement of an involved medical director may also be critical. A similar attitude may prevail in community hospitals. Referring physicians may find it unacceptable to relinquish care of a critically ill patient to nonphysician personnel. In an environment in which tertiary centers compete for patients, this may be a motivation for maintaining physician attendance during transport. Most referring physicians, however, are concerned only with transferring their patients in a safe and timely fashion. Anecdotal experience, as well as retrospective and prospective studies, suggests that properly selected and trained nurses provide a level of care during transport that approximates the level provided by physicians (5,16,17 and 18). Once a nonphysician team demonstrates competence and efficiency, the concerns of most referring physicians vanish.

Because the use of specially trained nonphysician personnel represents both a safe and economic alternative to physician participation in neonatal transport, most programs now rely on nonphysician personnel for patient care.

Because the use of specially trained nonphysician personnel represents both a safe and economic alternative to physician participation in neonatal transport, most programs now rely on nonphysician personnel for patient care.

Transport personnel must be proficient in cognitive knowledge of neonatal diseases, management principles of acute problems, and technical skills. The method and extent of training necessary to reach proficiency will depend on the type of personnel; however, the pattern of preparation will be similar for all professionals (19). Cognitive knowledge is best provided in didactic sessions in conjunction with self-study exercises. Management principles may also be taught in a didactic setting, but refinement of these skills requires repeated experiences in the inpatient setting. Laboratory simulation of technical skills, such as intubation, umbilical vessel catheterization, and thoracostomy tube placement, provides a good introduction to these procedures. These skills can then be refined in the inpatient setting under supervision. Demonstration of proficiency in these areas should be ensured by examination or observation by a qualified supervisor. After initial preparation, a period of training should be provided, during which the trainee accompanies a more experienced team member on transport. Final certification of competence should be awarded by both the medical director and the coordinator for the trainee’s professional group.

Communication

The quality of the communication system that supports a transport program may be the key determinant for its success. The communication system serves two basic functions: to provide a point of access for referring physicians, and to coordinate the activities of the transport team (20). A single call by the referring physician should provide access to all of the neonatal services of the tertiary center. The use of a toll-free hot line, often associated with a memorable acronym, is favored by some centers (21). Alternatively, referring physicians can call the NICU directly. If consultation is requested, the referring physician should be connected in a timely fashion with a consultant of appropriate training. If transfer is requested and deemed appropriate, an available bed in the NICU of the tertiary center, or an alternate center if necessary, should be identified. Bed procurement and all subsequent details of the transport should occur without additional calls by the referring physician.

Locating an available and appropriate site of care may be difficult because of a shortage of NICU beds or the lack of availability of subspecialty support in some areas. These regions often benefit from an organized system of identifying available resources. Several such programs exist and are of two varieties. In some areas, sophisticated computerized communication networks link neighboring centers (22). An alternative is an operator-assisted central referral or bed locator system. These systems speed the referral of patients and relieve both the referring physician and the physician at the tertiary center of the burden of placing numerous calls to locate a bed.

Once the decision is made to transport the patient and an admission bed is located, the role of the communications system shifts to dispatching the team and disseminating information about the transport. In this role, the system is best served by a communication center that is staffed and equipped for emergency medical service functions. The referring hospital should be informed of the estimated time of arrival and of any necessary preparations for the arrival of the vehicle. The receiving unit should be notified and be provided with medical information necessary for admission of the patient.

During the conduct of the transport, periodic communication between the dispatch center and the vehicle operator is advisable. Unexpected delays or mishaps are identified promptly and appropriate action taken. Some high-volume transport programs use satellite-tracking systems to monitor the movement of their transport vehicles, which can be exceedingly useful if diversion is necessary. When the transport team does not include a physician, the team should have the capability of communicating directly with the consulting physician at all times. This level of communication is mandated by some states’ nurse practice acts. Communication capabilities are usually a trivial problem while in the referring hospital, however they can present a challenge during transit. The gravity of this problem declines each year with the improvement of telecommunications equipment. Cellular phones are typically used during ground transport because of the broad coverage in most areas and the general familiarity of medical personnel with this type of communication. The use of VHF and UHF radios with patching devices to phone lines is an alternative during flight. Typically, air traffic control, medical control, and general communications have separate frequencies.

Many communication centers are equipped with automated devices that record all communications. Although not essential, the recorded transmissions may be valuable educational tools and aids in identifying system errors; in addition, they are often critical if a medicolegal question arises.

Communication should not end with the conclusion of the transport. The transport team should contact both the patient’s family and the referring facility to relate the events of the transport. The receiving physician should update the referring physician following admission and give further followup information at regular intervals, including at the patient’s discharge. This update should be expedited if an acute event occurs and should occur immediately in the event of death. Even with the ease of communication systems, failure to effectively communicate followup information remains one of the most common criticisms of tertiary care centers.

Financial Considerations

Subjecting a transport program to periodic cost-benefit analyses is a critical aspect of the program’s operation. The following elements should be included in the cost of operation:

Medical components

Nonphysician personnel salaries/benefits

Salary support of the medical director

Equipment and supplies

Medication

Expenses related to education of personnel

Nonmedical components

Administrative overhead

Vehicle operation, maintenance, insurance

Communications

Educational and marketing material

Identifying the costs associated with the program may be difficult if its operation is financially integrated into the operation of the NICU. For example, personnel costs often are difficult to quantify because, except in very high-volume programs, transport personnel usually contribute to inpatient services during transport duty time. Therefore, the cost allocated to the transport program should be discounted based on this contribution. The proportion of time devoted by the medical director is even more difficult to quantify and often is ignored in the financial analysis. The cost of equipment most easily separates from the cost of inpatient services as transport equipment rarely is used for other purposes. Included in estimates of equipment costs should be allowances for depreciation and maintenance.

The nonmedical components of a program are often more costly than the medical components because of expenses related to transportation. This is particularly true when air transportation is used. Sharing resources with other hospitals or agencies can minimize these expenses. Ground ambulances can be shared with local emergency medical service agencies or be used for convalescent transport. Aircraft can be used by a consortium of hospitals. The major disadvantage of the shared approach is the possibility of a vehicle being unavailable at the time of a request for transport; however, the potential for this occasional conflict may be far outweighed by the cost reductions.

The revenues of a transport program come from three general sources: reimbursement, support from governmental agencies, and support from other extramural organizations (23). Support from government and charitable organizations is unusual in the United States, and hospitals are increasingly dependent on reimbursement to support transport programs. Most third-party payers will reimburse the majority of the initial transport as long as the care rendered at the receiving hospital was unavailable at the referring hospital. Reimbursement for back transports is less consistent. In general, the cost of a transport program exceeds its revenues. Subsistence of the program, therefore, depends on financial assistance from the sponsor hospital.

The decision to fund a transport program usually is based on a favorable cost-benefit analysis. Providing a service that is unavailable at the outside hospital is clearly of benefit to the patient. Benefit can be quantified by reductions in mortality, morbidity, and length of hospital stay. Among low-birth-weight (LBW) infants with respiratory disease, one study has demonstrated that the services of a hospital-based neonatal transport team reduce hypothermia and acidosis, the greatest prognostic indicators of mortality (10). However, beyond this study little evidence exists to support the benefits of neonatal transport teams. In an attempt to quantify the benefits of a neonatal transport program, the most prudent approach may be to scrutinize carefully the type of patients being transported to ensure potential benefit from transport. These benefits should be combined with nonmedical benefits to the institution, such as improved public relations and the recruitment of new patients. Ultimately, many institutions in the United States elect to support a neonatal transport program, despite its financial disincentives, in order to increase occupancy of NICU beds.

A potential economy for transport programs may be to combine services, either within a program or between programs. An example of the former would be to cross-train members of specialty transport teams (e.g., pediatric, neonatal, and adult) such that the total number of personnel can be reduced. This strategy invariably results in some loss of expertise but may be necessary to ensure financial viability. Collaboration between programs may include sharing vehicles or teams. Smaller institutions may benefit from outsourcing entirely by contracting with larger medical centers for the provision of all transport services.

TECHNICAL ASPECTS

The Transport Environment

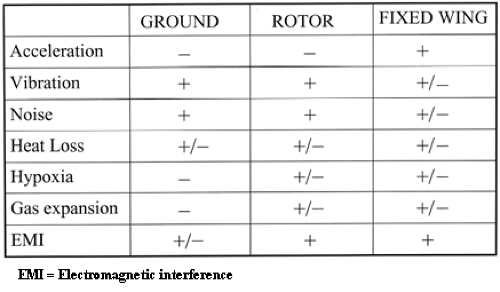

The principles of care provided during transport resemble the principles of inpatient care. Any differences in practice arise from the unique features of the transport environment (24). Many features—including excessive noise, vibration, improper lighting, variable ambient temperature and humidity, changes in barometric pressure, confined space and limited support services—can create problems during transport. The impact of these environmental factors relative to the mode of transportation is summarized in Fig. 4-2.

Noise

High sound levels, in the range of 60 to 70 decibels, are inherent to the NICU (25,26 and 27); but levels recorded on transport are significantly higher, on the order of 90 to 110 decibels (28,29). The effects of exposure to high sound levels on the neonate are not known, but the possibility of physiologic changes is suggested by studies of hospitalized infants (30,31). Brief exposure to high sound levels probably has little long-term effect on transport personnel; however, repeated exposure over time may result in hearing loss. Personnel should protect themselves from exposure by using sound-attenuating devices. Probably the most significant problem resulting from high sound levels is the inability to use auscultation to assess the patient. This handicap must be recognized before transport, and alternative methods for assessing heart rate and respiratory sufficiency must be available during transport.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree