Neonatal Syphilis

Pablo J. Sánchez

Jane D. Siegel

EPIDEMIOLOGY

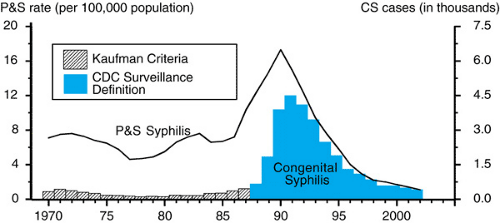

Congenital syphilis, a result of fetal infection with Treponema pallidum, remains a major public health problem worldwide. In the United States, from 1977 through 1990, a steady increase was seen in the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis among women (Fig. 81.1). This increase was greatest among African Americans and Hispanics of lower socioeconomic status who resided in large urban areas such as Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, and New York City. A major contributor to the increase of syphilis in these populations was the exchange of illegal drugs (notably crack cocaine) for sex with multiple partners whose identities were not known. Partner notification, a traditional syphilis-control strategy, was impossible to implement. Moreover, these women rarely sought prenatal care.

Subsequently, the number of cases of early congenital syphilis reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention increased from 108 in 1978 to more than 4,000 cases in 1991 (see Fig. 81.1). This dramatic increase was caused by both an increase in actual cases and the use of revised reporting guidelines. Beginning in 1989, the surveillance definition for congenital syphilis was broadened. The new definition includes not only all infants with clinical evidence of active syphilis, but also asymptomatic infants and stillbirths born to women with untreated or inadequately treated syphilis. Use of the new surveillance case definition increases the number of confirmed or presumptive cases of congenital syphilis by almost fourfold.

During the 1990s, a decrease in early syphilis was noted (see Fig. 81.1); this finding heightened expectations for the eventual control and even elimination of the disease in the United States. Syphilis rates had been at their lowest since reporting began in 1941, having declined 84% during the 1990s. This downward trend was attributed to innovative, community-based programs that identify locations with a high prevalence of syphilis, so-called core environments, such as specific sex-for-drugs locations, as well as core populations at high risk of infection, rather than on a sole reliance on named sexual contacts. Moreover, the awareness of the syphilis epidemic of the late 1980s resulted in wider serologic screening practices in clinics, emergency rooms, and hospitals. Since 2001, however, syphilis has increased among homosexual males, prompting concern for possible cotransmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In addition, syphilis continues to occur disproportionately in the rural southern United States.

PATHOGENESIS

Pregnant women with early syphilis are at highest risk of delivering infected infants. Among women with untreated primary, secondary, early latent, or late latent syphilis at delivery, approximately 30%, 60%, 40%, and 7% of infants, respectively, will be infected. Transmission of infection to the fetus usually occurs transplacentally from maternal spirochetemia, but the neonate also can be infected through contact with a genital lesion at the time of delivery. Although congenital infection can occur anytime during gestation, the risk of fetal infection increases as the stage of pregnancy advances. The theory that the Langerhans cell layer of the cytotrophoblast forms a placental barrier against fetal infection before the eighteenth week of pregnancy was disproved by demonstration of spirochetes in fetal tissue from spontaneous abortion at 9 and 10 weeks’ gestation and recovery of spirochetes from amniotic fluid at 14 weeks of pregnancy. Electron microscopy findings also disprove this theory by demonstrating the persistence of the Langerhans cell layer throughout pregnancy.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COMPLICATIONS

Syphilis during pregnancy is associated with premature delivery, spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, nonimmune hydrops, perinatal death, and two characteristic syndromes of clinical disease, early and late congenital syphilis. Early congenital syphilis refers to those clinical manifestations that appear within the first 2 years of life. Those features that occur after 2 years are designated as late congenital syphilis. The clinical manifestations and laboratory findings of early congenital syphilis may be present at birth or may be delayed for several months if the infant remains untreated. The physical signs are a direct result of active infection and inflammation.

Infants with congenital syphilis may be growth restricted at delivery. Hepatitis with hepatosplenomegaly occurs in 50% to 90% of affected infants. Splenomegaly does not occur without liver enlargement. Extramedullary hematopoiesis is seen in both the liver and spleen. Approximately one-third of infants have direct and indirect hyperbilirubinemia and elevated transaminase levels, which may worsen transiently after the initiation of penicillin therapy. Liver abnormalities may require more than 1 year to resolve, but they rarely lead to

cirrhosis. Generalized nontender lymphadenopathy occurs in 20% to 50% of cases, with characteristic involvement of the epitrochlear nodes. Hemolytic anemia with a negative Coombs’ test result is common. The peripheral leukocyte count can show either leukopenia or leukemoid reaction. Thrombocytopenia with petechiae and purpura occurs in approximately 30% of infants and may be the sole manifestation of congenital infection.

cirrhosis. Generalized nontender lymphadenopathy occurs in 20% to 50% of cases, with characteristic involvement of the epitrochlear nodes. Hemolytic anemia with a negative Coombs’ test result is common. The peripheral leukocyte count can show either leukopenia or leukemoid reaction. Thrombocytopenia with petechiae and purpura occurs in approximately 30% of infants and may be the sole manifestation of congenital infection.

Mucocutaneous lesions are specific for congenital syphilis and occur in 40% to 60% of affected infants. The rash of congenital syphilis usually is maculopapular and located on the extremities. The lesions are initially oval and pink but then turn coppery brown and desquamate. Desquamation occurs mainly on the palms and soles. A characteristic vesicular bullous eruption known as pemphigus syphiliticus may develop with erythema, blister formation, and eventual crusting as healing occurs (see color Fig. 128.8 in color section). Nasal discharge associated with rhinitis or snuffles is initially watery, but it may become thick, purulent, and even tinged with blood (Fig. 81.2). Nasal discharge and vesicular fluid contain large concentrations of spirochetes and are highly infectious. Rarely, mucous patches of the lips, tongue, and palate and condyloma lata in the perioral and perianal areas may occur.

FIGURE 81.2. Sniffles or rhinitis in an infant with early congenital syphilis. This mucous discharge develops after the first week of life. See Color Figure 81.2 in color section. (Courtesy of Dr. George H. McCracken, Jr., Dallas, TX.) |

Bone roentgenography shows skeletal abnormalities consisting of osteochondritis, periostitis, and osteitis in 80% to 90% of infants (Figs. 81.3 and 81.4). These abnormalities tend to be multiple and symmetric, with the lower extremities involved more often than the upper extremities. The long bones (tibia, humerus, femur), ribs, and cranium principally are affected. Rarely, bone lesions may be painful or have superimposed fractures resulting in pseudoparalysis of the affected limb (pseudoparalysis of Parrot). Osteochondritis involves the metaphysis and is evident roentgenographically approximately 5 weeks after fetal infection. Typical findings are metaphyseal demineralization and a radiodense band below the epiphyseal plate that represents a widened and enhanced zone of provisional calcification. An underlying zone of osteoporosis is evident as a radiolucent band. Bilateral demineralization and osseous destruction of the proximal medial tibial metaphysis are referred to as Wimberger sign (see Fig. 81.3). The classic transverse saw-toothed appearance of the metaphysis (see Fig. 81.4)

often is not seen on plain roentgenography but is evident on xeroradiography of long bones of stillborn infants with congenital syphilis. Periostitis requires 16 weeks for roentgenographic demonstration and consists of multiple layers of periosteal new bone formation in response to diaphyseal inflammation. Osteitis creates a “celery stalk” appearance in long bones (see Fig. 81.3), resulting from involvement of the medullary canal with resultant diaphysitis. After several months, complete healing of the affected bones occurs, even without antibiotic therapy.

often is not seen on plain roentgenography but is evident on xeroradiography of long bones of stillborn infants with congenital syphilis. Periostitis requires 16 weeks for roentgenographic demonstration and consists of multiple layers of periosteal new bone formation in response to diaphyseal inflammation. Osteitis creates a “celery stalk” appearance in long bones (see Fig. 81.3), resulting from involvement of the medullary canal with resultant diaphysitis. After several months, complete healing of the affected bones occurs, even without antibiotic therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree