Eryn Hart Dutta, DO

INTRODUCTION

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) is considered a “normal” part of pregnancy, with every woman experiencing a myriad of symptoms to varying degrees for a period of time starting in early pregnancy. In the more severe cases, hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) can develop, often requiring a prolonged hospital admission with pharmacotherapeutic management. As a result, early recognition and implementation of a management strategy is crucial. These strategies consist of more conservative measures like dietary and lifestyle modifications, to oral pharmacotherapy in an outpatient setting or intravenous pharmacotherapy in the inpatient setting. Once a treatment plan is implemented, counseling regarding adherence is essential in order to prevent progression or relapse of symptoms.

Reflux is another common problem that may precede the onset of pregnancy, begin with the onset of NVP, or worsen as the pregnancy progresses. Like NVP, the normal physiologic changes of pregnancy contribute to its development and often make management difficult. Unlike NVP, symptoms may persist well into the second or third trimesters due to the enlarging uterus and displacement of the intra-abdominal organs and lower esophageal sphincter. Comanagement of NVP and reflux is often necessary in order to maximize treatment benefit. The aim of this chapter is to present the clinical presentation; diagnosis and management strategies of NVP, HG, and reflux; and the more infrequent occurrence of ptyalism in pregnancy.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

NVP and HG

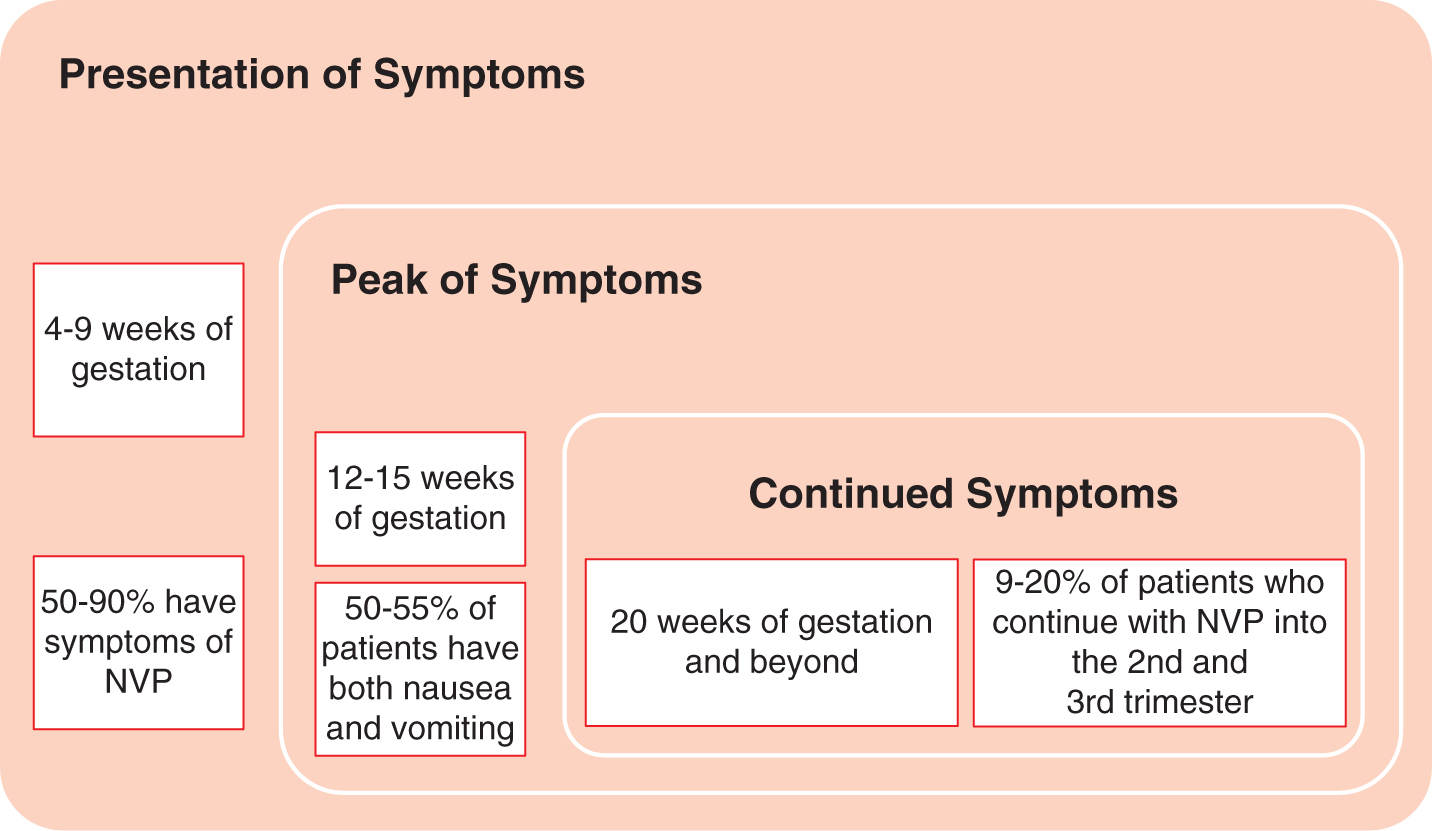

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) is a very common medical condition in pregnancy that often goes underdiagnosed and/or undertreated. The symptoms of NVP occur in 50% to 90% of pregnancies, with approximately 50% to 55% of patients having both nausea and vomiting and 25% with nausea alone.1–7 Despite the fact that NVP is often referred to as “morning sickness,” symptoms can occur at any time of the day, last for varying periods of time and vary from day to day. The usual onset of NVP is between 4 and 9 weeks gestational age, with maximal symptoms at 12 to 15 weeks, and resolution by 20 weeks gestational age.1,4,8 There are a small percentage of pregnant women (approximately 9%-20%), however, who experience symptoms beyond 20 weeks gestational age and into the late second and third trimesters or until delivery8,9 (Figure 21-1). Conservative measures are successful at treating symptoms in most cases, with NVP following a benign and typical clinical course. However, some women will require multiple visits to the ER, provider’s office or labor and delivery triage with inpatient admission for the more severe cases of NVP.

FIGURE 21-1. Clinical presentation of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.

Although the physical examination in patients with NVP is typically benign and vital signs are normal, careful history taking and thorough examination are still necessary to rule out any contributing or coexisting medical conditions. The symptoms of NVP can include any combination of the following: nausea, gagging, dry retching, dry heaving, vomiting, and odor/food aversions.10–12 In addition, women will typically have certain precipitating factors that trigger the nausea and/or vomiting episodes, that is movement, heartburn, certain foods, and/or odor triggers.13 If symptoms are prolonged and/or severe, dehydration is likely present, and clinical signs may include tachycardia, postural hypotension, and dry mucous membranes.14

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) occurs in 0.3% to 3% of pregnancies and is typically defined as severe and persistent nausea and vomiting with or without retching, with a loss of 5% or more of prepregnancy body weight, electrolyte abnormalities, ketonuria, dehydration, and potential vitamin (ie, thiamine) or mineral deficiencies.1–7

The symptoms reported with HG are similar to that seen with NVP, only to a greater degree. If the symptoms are prolonged and/or severe and dehydration is present, the patient may have orthostasis, muscle wasting, weakness, or signs of central nervous system abnormalities on clinical presentation.14 A majority of women with these findings will require hospital admission for control of their symptoms. It is particularly important to ascertain the duration of vomiting episodes in these patients to assess the risk for Wernicke encephalopathy, a neurologic emergency that will be discussed later.

Reflux

Approximately 40% to 85% of pregnant women will report symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) during pregnancy, with 50% of women reporting symptoms in the first trimester.12,15 Symptoms include heartburn, belching, indigestion, retrosternal discomfort, regurgitation, and an acid taste in the mouth that worsen as the pregnancy progresses.14–17 A prospective cohort study by Naumann and colleagues, 2012, examined the risk factors, treatment, and outcomes for nausea/vomiting and heartburn during pregnancy.16 They found that prepregnancy heartburn, multigravidity, higher prepregnancy body mass index, and increased pregnancy weight gain were all independent risk factors for heartburn. A prospective longitudinal cohort study by Malfertheiner et al, 2012, assessed the prevalence and severity of GERD symptoms during pregnancy.17 They found that the symptoms of GERD were present in 26% of women in the first trimester, 36% in the second trimester, and 51% in the third trimester. Finally, complications of GERD, esophagitis and structure formation, are infrequent in pregnancy.

As seen with NVP and HG, the hormonal changes of pregnancy likely play a significant role in the development of these symptoms with estrogen and progesterone causing a decrease in the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter by approximately 50%.16 This, in addition to the increase in intra-abdominal pressure from the growing uterus and slower GI transit time, predisposes the pregnant woman to the symptoms of GERD.17 In contrast to the symptoms of NVP/HG, the symptoms of GERD are likely to present later in pregnancy and worsen as the pregnancy progresses, and women with preexisting GERD are more likely to experience more severe symptoms of NVP/HG.15,16 Finally, it is not uncommon for women to present on the first trimester with NVP or HG and have coexisting symptoms of GERD. As a result, inquiry into whether GERD is present should occur and both conditions should be treated. Symptoms of GERD typically resolve soon after delivery.

Ptyalism Gravidarum

Ptyalism gravidarum, or sialorrhea, occurs in up to 2.4% of pregnancies.18 It is in the spectrum of disease of NVP and HG. In fact, 60% of patients with HG will also have excess salivation or the more extreme diagnosis of ptyalism.19 The disorder typically starts in the first trimester of pregnancy and can be associated with and preceded by NVP or HG. It was once thought that ptyalism only occurred in pregnant women with underlying psychosis; however, it has since been shown that there is a predominant physiologic basis for this disorder. It is known that progesterone and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) are responsible for increased salivary viscosity in the first trimester followed by increased salivary production throughout the remaining trimesters due to gastric acid production.20,21 Another possible etiology of this condition is stimulation of the parasympathetic nerve supply of the salivary glands which induces excessive salivation during pregnancy.20,21

Although there is a mild increase in salivation in normal pregnancy, ptyalism is excessive salivary secretion that may persist throughout all trimesters of pregnancy and even until delivery in some cases.21–23 In addition, these patients also exhibit an ostensible inability or difficulty in swallowing their saliva, which forces them to continuously spit in a cup or other container throughout the pregnancy.24 Some patients report that attempting to swallow the saliva precipitates episodes of nausea.25 On presentation and physical examination, women may have distended cheek pouches, speech difficulties due to swollen salivary glands, excoriation of the buccal mucosa, maceration of the skin around the mouth, and an enlarged, coated, red tongue.18,23,26 This excessive salivation often becomes distressing to the pregnant woman due to feelings of embarrassment and being uncomfortable. As a result, there may a significant psychosocial impact on her daily activities throughout the pregnancy.

DIAGNOSIS

NVP and HG

Regardless of when the patient presents, it cannot always be assumed that nausea and vomiting is due to NVP. It is more appropriate to take the pregnancy-related versus nonpregnancy-related approach when determining the etiology, even in the first trimester.10 During initial history taking, questioning on the onset, timing, severity, and aggravating and alleviating factors may point to another cause for the nausea and vomiting. Although it is most likely NVP if the patient initially presents with symptoms before 10 weeks, a thorough history and physical examination and confirmation of pregnancy is still required to elicit any potential contributing or confounding factors. If symptoms present for the first time after 10 weeks of gestation, NVP/HG are unlikely to be the cause.27 If NVP is suspected, no specific laboratory testing is indicated.

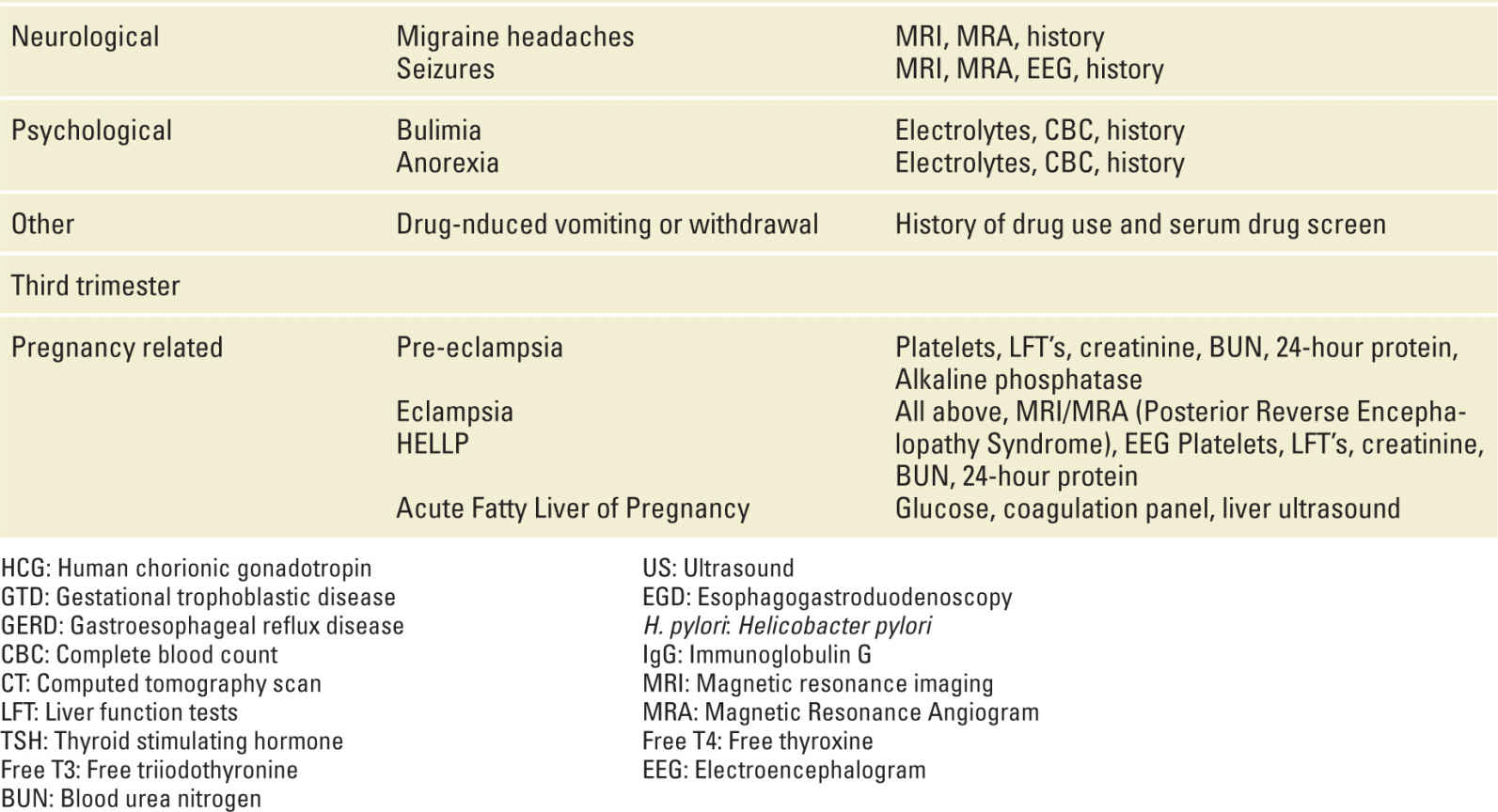

HG is the most extreme form of NVP, and is considered a diagnosis of exclusion.28 If HG is suspected, a more comprehensive workup is indicated and other causes of the nausea and vomiting should be considered. Moreover, because HG often recurs in subsequent pregnancies, reported absence of similar symptoms in a prior pregnancy makes the diagnosis of HG less likely.29 Hospitalization is necessary if the patient is not tolerating food and liquids because of severe persistent vomiting and outpatient management has failed.4 The patient should be evaluated for urinary ketones and specific gravity, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), amylase, lipase, bilirubin, glucose, and electrolytes (ie, hyponatremia and hypokalemia).30 Electrolyte abnormalities may be manifested as a hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis or metabolic acidosis with significant volume depletion.31

In the more severe cases of nausea and vomiting, evaluation of thyroid function may be necessary. Physiologic stimulation of the thyroid gland is common in early pregnancy due to the structural similarity between the α-subunit of hCG and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), or thyrotropin.32 Because hCG cross-reacts with TSH, thus stimulating thyroid gland production of thyroid hormones, TSH, free T4 (FT4), and free T3 (FT3) should be checked.30 TSH may be low and FT4 may be normal to high normal, or even high, in patients with HG, which is similar to that seen in Graves disease, but without the clinical symptoms and findings of Graves disease or thyroid antibodies.33 Approximately 70% of patients with severe NVP or HG will have a low TSH and high FT4.33 This form of transient hyperthyroidism or biochemical thyrotoxicosis usually resolves by 20 weeks gestational age without specific treatment.14 However, if the patient has clinical signs and symptoms or a personal history of hyperthyroidism, and/or a goiter on physical examination, pharmacologic treatment is indicated and may help with managing symptoms of NVP/HG.

Prolonged nausea and vomiting in the setting of NVP or HG can lead to maternal vitamin and mineral deficiencies. As mentioned above, Wernicke encephalopathy is a potential serious or fatal maternal complication due to severe vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency. Approximately 47% of patients with this condition will present with a history of prolonged nausea and vomiting along with the triad of abnormal ocular movements, ataxia, and confusion; an additional percentage will also have diplopia.32,34 Symptoms can also be more variable and include memory loss, apathy, autonomic disturbances, decreased level of consciousness, or blurred vision.34,35 Although this condition is reversible with prompt treatment, 60% of women will have residual impairment and there is a 37% fetal loss rate.34 In addition, permanent neurologic defects or maternal death can occur in severe deficiency. Because maternal serum thiamine levels are not useful in making the diagnosis, any pregnant woman who presents with prolonged nausea and vomiting and neurologic abnormalities should be empirically treated with intravenous (IV) thiamine.

Deficiencies in vitamins B6 and B12 are rare and not as potentially serious but can cause anemia and peripheral neuropathy associated with hematemesis, malnutrition, and psychological effects.32 Although rare, Vitamin K deficiency and coagulopathy can also occur, leading to an abnormal coagulation profile and bleeding.36 Folic acid, calcium, and iron deficiencies may also be present. If any of these deficiencies are suspected, appropriate laboratory testing should be done, especially if the patient has a history of disorders of the GI tract or gastric bypass surgery (Table 21-1).

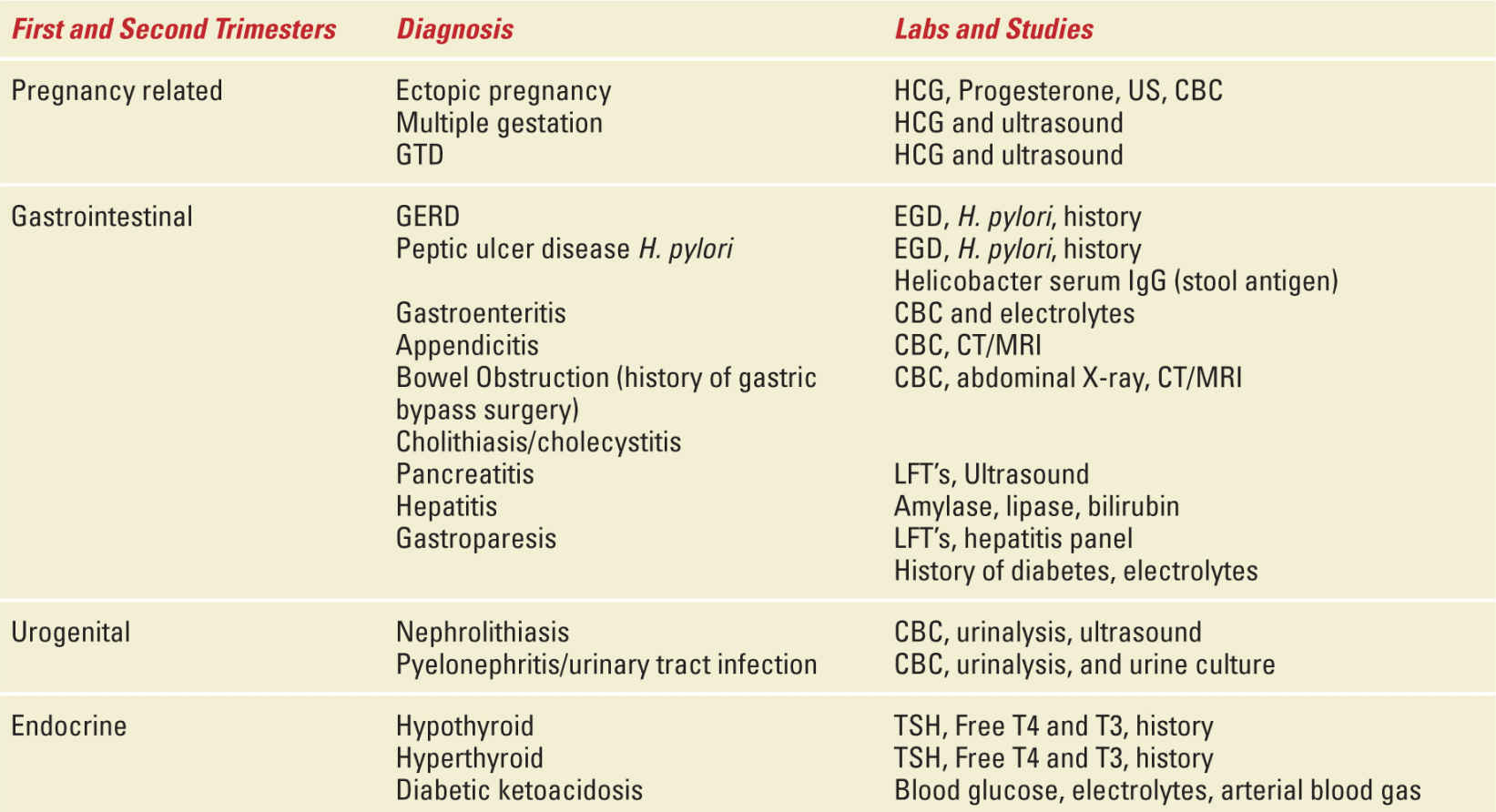

Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy-Differential Diagnosis by Trimester |

Other Causes of NVP

If NVP or HG have been diagnosed and there is poor response to initial interventions or an atypical presentation occurs (eg, abdominal pain precedes onset of vomiting or presentation starts late in pregnancy), other causes of nausea and vomiting must be explored such as infections, cholecystitis, appendicitis, pancreatitis, thyroid disease, and diabetic ketoacidosis.3,4,6,7 If there is fever or leukocytosis, a source of infection should be sought (ie, pyelonephritis, hepatitis, meningitis). Specific signs, such as peritoneal irritation, severe epigastric pain radiating to the back, bilious emesis, or changes in bowel habits, should raise the suspicion for GI disorders. Nausea and vomiting associated with right upper quadrant pain and hypertension should raise the suspicion for preeclampsia or acute fatty liver of pregnancy.10,29 Elevated aminotransferases could be a result of persistent nausea and vomiting secondary to volume depletion and ischemic hepatitis or be the result of acute or chronic hepatitis infection.29 If hematemesis is present, a Mallory-Weiss esophageal tear from prolonged vomiting or a GI ulcer may be the cause. Finally, metabolic disorders such as diabetic ketoacidosis should always be considered. Serum glucose, electrolytes, and ketones should be obtained to assess for this risk (Table 21-2).

TABLE 21-2 | Potential Laboratory Abnormalities and Signs/Symptoms with HG |

Reflux

The diagnosis of GERD in pregnancy is similar to that in the nonpregnant patient. It is primarily based on symptoms and/or a prior history of the condition. A thorough history and physical examination are still necessary in order to rule out more serious sequelae of GERD. There is no specific laboratory testing recommended, unless coexisting Helicobacter pylori infection is suspected. If H. pylori is suspected, testing for the presence of the stool antigen is recommended. Invasive studies such as endoscopy and other radiographic studies are typically not performed during pregnancy because of the potential maternal risk and fetal exposure. If it is decided that invasive testing should be done because of severe and refractory symptoms, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) can be performed with adequate anesthesia and maternal and fetal surveillance.37

Ptyalism Gravidarum

The diagnosis of ptyalism is based on clinical presentation. There are no defined physical or biochemical abnormalities with this disorder. Currently, there is no recommended laboratory testing.

MANAGEMENT

NVP and HG

Patients with NVP may be conservatively managed with dietary and lifestyle changes, outpatient pharmacologic treatment or may require multiple triage visits for IV fluid hydration and antiemetics, with inpatient admission in the more severe cases. It is important to remember that every woman is different, experiences different symptoms, and has her own perception of disease severity and desire for treatment. If a woman primarily experiences nausea, this should not be dismissed as nausea alone as it can be more disruptive and affect quality of life to a greater degree than episodes of vomiting. In addition, early recognition and initiation of treatment is essential in

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree