Fig. 1

Bado classification of Monteggia fractures (Courtesy of Dan A. Zlotolow, MD)

A modification of Bado’s classification was described specifically for children by Letts and associates (Letts et al. 1985). Five types were described with type A, B, and C subtypes of Bado’s type I anterior radial head dislocation. In Letts’ type A, the dislocation is accompanied by plastic deformation of the ulna with an apex anterior deformity (Fig. 2). Type B is a greenstick fracture of the ulna, and type C is a complete fracture of the ulna (Fig. 3). A Lett’s type D corresponds with a Bado type 2; a Lett’s type E corresponds with a Bado type 3.

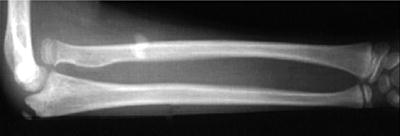

Fig. 2

Acute Monteggia fracture with ulnar plastic deformation

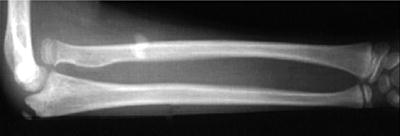

Fig. 3

Acute Monteggia fracture with anterior radial head dislocation

Acute Injury Diagnosis/Assessment

Monteggia fractures are uncommon in childhood and can be easily misdiagnosed. Correct diagnosis and early treatment is essential to avoid elbow dysfunction and chronic dislocation of the radial head. An injury should always be suspected when a child presents with a painful elbow and limited motion after a fall. A child with a Monteggia injury will demonstrate pain, swelling, and possible deformity of the forearm and elbow. On exam, both flexion-extension and pronation-supination will be painful and limited. Obvious dislocation may be noted with careful palpation of the radial head. Palpation along the length of the ulna will also be painful. If there is plastic deformation along the ulna, a step-off may not be present. A careful neurovascular exam should be undertaken with special attention to the radial and posterior interosseous nerve. Although less common, median and ulnar nerve injuries have also been described (Li et al. 2013).

Imaging

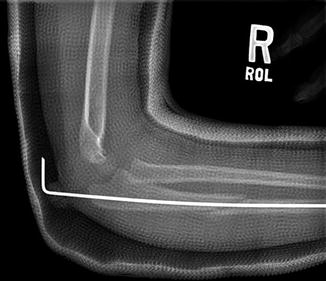

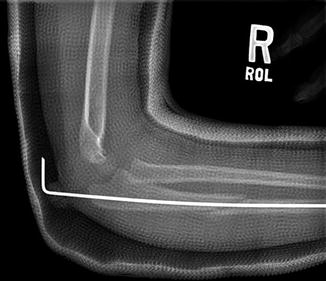

It is essential to obtain radiographic studies of the elbow with true anteroposterior and lateral views. The most common reasons for missed Monteggia fractures are inadequate radiographs and inaccurate interpretation of the radiographs (Gleeson and Beattie 1994). With any suspicion of injury to the elbow, high-quality dedicated radiographs must be taken. To avoid missing a Monteggia fracture, several assessments should be made on radiography. The radial head must be carefully examined for congruency and alignment with the capitellum. A line drawn through the longitudinal axis of the radius should align with the capitellum on all radiographic views regardless of elbow position. Additionally, plastic deformation of the ulna is unique in children and should lead to careful scrutiny for radiocapitellar dislocation. The ulnar bow sign can assist in making the correct diagnosis (Lincoln and Mubarak 1994; Degreef and De Smet 2004). On a true lateral plain radiograph of the elbow, the ulnar bow line is drawn along the dorsal border of the ulna from the olecranon to the distal metaphysis. The ulna normally has a linear border and any deviation from this line may signify injury. When plastic deformation occurs, the location of maximum deformity is usually found to be near the mid-ulna (Lincoln and Mubarak 1994).

Acute Injury Treatment

The goal of treatment in acute Monteggia fractures is restoration of the length and alignment of the ulna and reduction of the radiocapitellar joint. Usually, anatomic reduction of the ulna will reduce the radiocapitellar joint. The rich vascular supply and periosteum surrounding the pediatric elbow contributes to a rapid healing response. It is critical to recognize and treat an acute Monteggia fracture before chronic misalignment occurs. If delayed beyond 1 week, a closed reduction of the radiocapitellar joint may no longer be possible (Ring and Waters 1996).

In acute Monteggia fractures, management depends upon the type of ulnar injury (Ring et al. 1998). With plastic deformation or incomplete fracture of the ulna, a closed reduction with cast immobilization is performed. Following closed reduction, the radiocapitellar joint can be reduced with a combination of elbow flexion, supination, and direct manipulation over the radial head. The elbow should be immobilized in 90° of flexion and full supination (Bado 1967; Kay and Skaggs 1998). With complete fractures of the ulna, there is a risk of displacement and loss of joint reduction after closed reduction and cast immobilization (Olney and Menelaus 1989, Ring and Waters 1996, Nakamura et al. 2009). Operative treatment is necessary if stable reduction is not achieved (Table 1). With a transverse or short oblique fracture, closed reduction with intramedullary wire/nail fixation is often necessary (Fig. 4). If fixation with an intramedullary wire/nail is not stable, a construct with plate and screws may be needed (Table 2). Complete fractures with a long oblique pattern are more unstable and prone to collapse or shortening. Fixation with plate and screws is usually necessary to achieve stable fixation in this fracture pattern.

Table 1

Preoperative planning for acute Monteggia fracture

Operative fixation for acute Monteggia fracture |

|---|

Preoperative planning |

OR table: standard with hand table |

Position/positioning aids: supine, body position at edge of table allowing for fluoroscopy |

Fluoroscopy location: approach from end of hand table |

Equipment: Kirschner wires, flexible titanium intramedullary nails, small fragment compression plating system |

Tourniquet: sterile, proximal |

Fig. 4

Acute Monteggia fracture with closed reduction and intramedullary nail fixation

Table 2

Surgical steps for acute Monteggia fracture

Operative fixation for acute Monteggia fracture |

|---|

Surgical steps |

Initial closed treatment of ulnar fracture |

Reduction of radiocapitellar joint |

If unstable with transverse or short oblique ulnar fracture, intramedullary nail fixation with insertion through proximal olecranon |

If unstable with long oblique or comminuted ulnar fracture, plate fixation using longitudinal incision over the fracture site |

If radiocapitellar joint irreducible, extended Kocher approach with joint exploration |

Assess elbow stability after reduction and fracture fixation |

Anatomic reduction of the ulna usually allows stable reduction of the radiocapitellar joint. However, radiocapitellar joint reduction may be blocked by soft tissue interposition including the capsule, annular ligament, and/or posterior interosseous nerve. An irreducible joint warrants exploration, especially in the setting of a posterior interosseous nerve palsy, which may signify nerve entrapment (Rahbek et al. 2011; Eygendaal and Hillen 2007; Li et al. 2013). After fracture fixation, the ligamentous stability of the elbow should be assessed. Occasionally, the lateral ulnar collateral ligament is disrupted and requires open repair.

Loss of reduction is important to recognize after acute treatment. Weekly reevaluation following initial treatment allows assessment for recurrent radial head dislocation or subluxation (Table 3). This is more common with isolated closed reduction of the ulna. When promptly recognized, a repeat closed reduction with fixation is performed.

Table 3

Postoperative protocol for acute Monteggia fracture

Operative fixation for acute Monteggia fracture |

|---|

Postoperative protocol |

Type of immobilization: long arm cast |

Length of immobilization: 4–6 weeks or until evidence of fracture healing |

Rehab protocol: early active range of motion after fracture healing; gradual return to full weight-bearing |

Return to sport protocol: gradual increase in weight-bearing; return to contact sports at 3 months |

Acute Monteggia Preferred Treatment

In the acutely diagnosed Monteggia fracture, closed reduction with cast immobilization is the initial and preferred treatment for children. This can be accomplished with anatomic reduction of the ulna which generally provides a stable and anatomically reduced radiocapitellar joint. After a careful preoperative evaluation, longitudinal traction and reduction of the ulnar fracture is performed. The elbow is then flexed and direct pressure applied over the radial head guiding reduction. With the radial head reduced, the elbow is examined in pronation and supination to assess the most stable position. The elbow is then immobilized in approximately 90° of flexion in the most stable position of pronation or supination.

After closed reduction and long arm cast application, accurate postreduction radiographs are obtained. All views should demonstrate a reduced radiocapitellar joint. The patient then returns for weekly radiographic reevaluation, including dedicated forearm and elbow series, for the first 3 weeks following the manipulation. If the fracture alignment and radiocapitellar joint reduction are maintained, the patient returns at 6 weeks postreduction for cast removal and a new series of radiographs. It is important to obtain radiographs of the forearm as well as true radiographs of the elbow.

If anatomic reduction is not possible with closed treatment, operative treatment is indicated. With a transverse or short oblique ulnar fracture, fixation is attempted with an intramedullary nail. If the ulnar fracture is long oblique, comminuted, or unstable to pin fixation, plate fixation is performed.

Occasionally the radiocapitellar joint is irreducible after anatomic reduction of the ulna. Soft tissue interposition may be blocking the reduction which may involve a torn annular ligament, an osteochondral fragment, or the posterior interosseous nerve. Open reduction and evaluation of the elbow joint is performed. An open lateral approach using the extended Kocher interval is performed. The radiocapitellar joint is visualized and examined for any interposed soft tissue. If the preoperative evaluation demonstrated a posterior interosseous nerve palsy, then the fracture is carefully examined for incarceration of the nerve. After removal of any soft tissue, the joint is reduced and checked for stability. The annular ligament is not routinely reconstructed (although it may be repaired) and a transcapitellar pin is not used since the radiocapitellar joint is stable if the ulnar fracture is anatomically reduced.

After open reduction and ulnar fixation, the arm is immobilized for 4–6 weeks in a long arm cast. The arm is casted in 90° of flexion and the most stable position of pronation or supination. The patient is brought in for weekly follow-ups including dedicated elbow radiographs, for the first 3 weeks after surgery, to ensure the joint remains reduced.

Chronic Injury Diagnosis/Assessment

If the acute Monteggia fracture is not recognized, a persistent radiocapitellar dislocation will result. The pediatric elbow is well vascularized and fracture healing and remodeling occurs quickly. The natural history of the child with a chronic Monteggia fracture includes pain, loss of motion, progressive cubitus valgus deformity, and instability. Subsequent tardy ulnar nerve palsy may also develop.

The missed Monteggia fracture results in a chronic dislocation of the radial head that becomes more disabling with time (Nakamura et al. 2009; Rahbek et al. 2011). The initial injury may be misdiagnosed between 16 % and 33 % of the time, especially with plastic deformation of the ulna (Dormans and Rang 1990). Up to 60 % of children may develop significant pain and up to 50 % may develop limited range of motion with conservative treatment alone (Nakamura et al. 2009). Left untreated, the radial head undergoes hypertrophic change with loss of the articular surface concavity (Fig. 5). This is accompanied by flattening of the capitellum. With time a valgus deformity of the radial neck may also develop. These morphological changes result in the radial head failing as a component in elbow stability. With time a progressive cubitus valgus deformity develops (Fig. 6). This may place the ulnar nerve on increasing stretch and friction resulting in potential for a late ulnar nerve palsy. Both posterior interosseous and median neuropathies have also been described in missed Monteggia injuries (Chen 1992; Nakamura et al. 2009).