Chapter 11 Miscarriage and abortion

AETIOLOGY OF SPONTANEOUS MISCARRIAGE

The causes of miscarriage are:

Implantation

In the early weeks of pregnancy (0–10 weeks) ovofetal factors account for most miscarriages; in the later weeks (11–22 weeks) maternal factors become more common (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1 Aetiological factors in 5000 abortions

| FACTOR | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|

| Fetal or ovular | |

| Defective ovofetus | 60 |

| Defective implantation or activity of trophoblast | 15 |

| Maternal | |

| General disease | 2 |

| Uterine abnormalities | 8 |

| Psychosomatic | ?15 |

Maternal factors

Systemic maternal disease (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus), and particularly maternal infections, account for 2% of miscarriages. A further 8% are associated with uterine abnormalities, such as congenital defects, uterine myomata, particularly submucous tumours, or cervical incompetence (see p. 104). Psychosomatic causes have been suggested as leading to miscarriage, but the evidence is difficult to evaluate. Women who smoke 10 cigarettes or more per day double their risk.

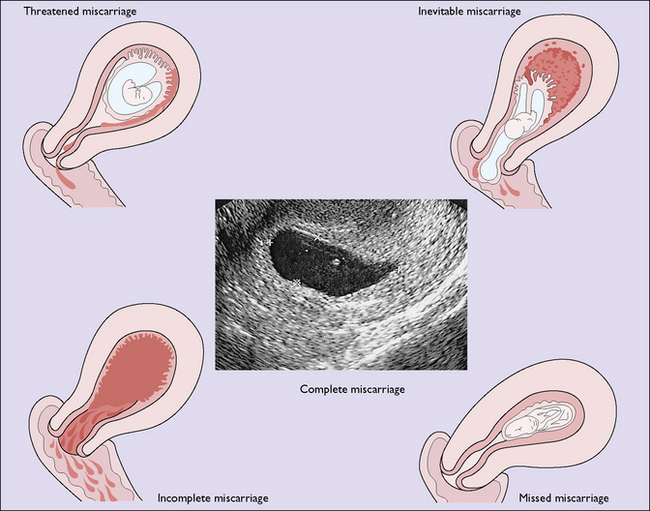

VARIETIES OF SPONTANEOUS MISCARRIAGE

For descriptive purposes the miscarriage is classified according to the findings when the woman is first examined, but one kind may change into another if the aborting process continues. If infection complicates the miscarriage, the term septic miscarriage is used. The various types of miscarriage are shown in Figure 11.1 and each will be considered separately later.

Threatened miscarriage

A real-time pelvic ultrasound examination will clarify the diagnosis. This may show: