Mental Retardation

Pasquale J. Accardo

Jennifer A. Accardo

Arnold J. Capute

In the English-speaking world, the terms intellectual disability or cognitive impairment are replacing the term older mental retardation (see Box 98.1 for an overview of the history of the definition, diagnosis, and treatment of cognitive impairment). Global learning disability is preferred in England proper. All these terms characterize serious deficits, predominantly in the cognitive realm, rather than a medical diagnosis. Like cerebral palsy, intellectual disability is best understood as a family of syndromes with similarities that render considering individual clinical presentations separately less helpful to the medical management of the child. Despite much debate among professionals about the model approach to cognitive impairment, the paradigm of the child with brain damage (static encephalopathy) remains the point of departure from which the pediatrician can best pursue diagnosis and counseling.

DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION

The definition of intellectual disability (the 317 to 319 codes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [DSM-IV-TR] for mental retardation) has three components:

Some degree of cognitive delay

Impaired adaptive behavior

Onset before 18 years of age

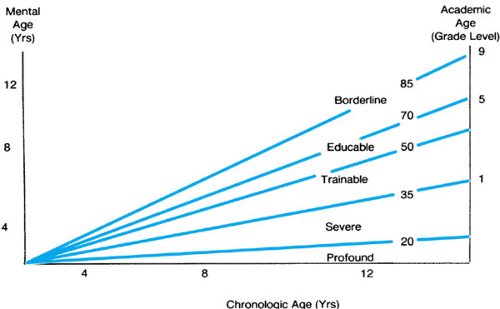

Cognitive delay is delineated by the IQ, with the levels of mental retardation roughly correlating with the number of standard deviations below the mean (Fig. 98.1). It is as imperative in intellectual disability as in other developmental disorders to remember that no child or adult ever can be reduced to a single number, such as IQ. Human behavior does not admit such simplistic reductionism. The limited utility of IQ scores is further confused by such variables as chronic disease; sensory deficits; prematurity; environmental deprivation; intensive stimulation; the skill and experience of the examiner; the race, gender, and age of the child; the bias of the instruments used; and the interfering presence of behavioral and emotional disorders in the child and the family. These complicating factors need not reduce the IQ score to insignificance; they should instead be viewed as part of the complex clinical circumstances in which children’s cognitive behavior is assessed, just as physicians know to interpret quantitative laboratory tests within a broader clinical context. These difficulties also highlight the importance of special competence for the pediatrician attempting to formulate a developmental diagnosis.

The single most important qualification for a diagnosis of intellectual disability remains a validly obtained IQ score of more than two standard deviations below the population mean for the test. Subject to various qualifications, the specific IQ score is the deciding basis for developmental diagnosis, biomedical assessment, parent counseling, educational habilitation, vocational rehabilitation, and disability determination. For using and interpreting the test instruments, the IQ cutoffs for the different levels of retardation (e.g., 70, 50, 35, 20) are more accurately viewed as ranges (e.g., 65 to 75, 45 to 55, 30 to 40, 15 to 25). Using IQ ranges allows a better correlation with cognitive level. In contrast to the more statistically defined field of psychometrics, the measurement of adaptive behavior is less precisely quantified. Clinical judgment of self-help and socialization skills can be aided by instruments such as the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS).

The third criterion, onset before 18 years of age, is least problematic because most cases of intellectual disability are

congenital, prenatal, or perinatal, and the onset and diagnosis are rarely delayed until adolescence. The rare cases of dementia (i.e., degenerative central nervous system [CNS] disease) and postnatally acquired brain damage are readily recognizable.

congenital, prenatal, or perinatal, and the onset and diagnosis are rarely delayed until adolescence. The rare cases of dementia (i.e., degenerative central nervous system [CNS] disease) and postnatally acquired brain damage are readily recognizable.

BOX 98.1 History

Cognitive impairment was recognized in the ancient and medieval worlds, but little interest was exhibited in pursuing the problem beyond the bare minimums necessary to resolve questions of property rights. Radical conceptual changes in the philosophy of human nature and significant advances in science had to occur before the right questions could be posed. The requisite progress came together at the time of the French Revolution. Victor, a “feral child” found in the woods at Aveyron, was pronounced an idiot by Pinel, one of the founders of modern psychiatry. Itard received one of the first government research grants to attempt to educate this significantly delayed boy. Over a 5-year period, Itard virtually invented the discipline of special education and pioneered much of behaviorist psychology. His student, Seguin, continued working on habilitation techniques and became an influential leader of the new residential school movement when he emigrated to the United States. With few changes, the special education methodologies these two physicians devised to help persons with mental retardation became the foundation for the early childhood education system popularized in the first half of the twentieth century by a third physician, Maria Montessori.

In the early nineteenth century, Esquirol differentiated “imbeciles” from three classes of more severely limited “idiots” by their functional ability to use language. In 1877, Ireland published the first modern medical textbook on mental retardation, On Idiocy and Imbecility, in which he proposed an etiologic classification that would remain valid for most of the next century. Ireland’s book also publicized the 1866 description by Down of one of the first specific mental retardation syndromes. However, until 1959 when Lejeune identified the specific chromosomal trisomy, difficulty in clinically differentiating Down syndrome from cretinism and other disorders persisted. The pseudoscientific eugenics movement of the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries precipitated sterilization laws and euthanasia practices and distorted the initial idealism of the educational movement pioneered by Itard and Seguin. The flowering of the age of syndrome identification and molecular genetics in the latter half of the twentieth century somewhat redeemed the contribution of scientific genetics to the study of intellectual disability.

Major progress in the medical and behavioral areas depended heavily on the development of well-designed psychometric instruments for accurate classification. In 1905, the psychologist Binet and the physician Simon published the first standardized intelligence test (later translated into English at Stanford University). This advance ushered in more than half a century of use and abuse of psychometric instrumentation that only partially filled the authors’ original intentions of introducing an objective and unbiased measurement device to replace the subjective and sometimes arbitrary opinion of the classroom teacher and untrained professionals. The pediatrician and psychologist Gesell was the first to extend the quantification of development to the period of infancy and early childhood, and his assessment approach avoided some of the major pitfalls of IQ mismeasurement: (a) test scores did not stand alone but acquired meaning only within the broader context of past history, biological risk and repeated assessments, and (b) the dissociation between the various streams of development was used to focus the medical evaluation.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Despite continued medical advances in prenatal maternal care and the prenatal and perinatal treatment of the fetus and newborn, the overall incidence of intellectual disability has remained relatively stable at approximately 2% to 3% of the population. More than 80% of all persons with intellectual disability are in the mildly delayed range, with twice as many male as female patients. Atypical children with the developmental pattern of normal to borderline intelligence and superimposed language disorders and other deviance or dissociation can be misclassified as intellectually disabled. The recent increase in the occurrence of autism has resulted in large part from a reclassification as autistic of children who previously

would have been called mentally retarded. Careful attention to the pattern of delayed language and socialization skills in the presence of intact to superior nonverbal problem-solving skills should allow the identification of such children as autistic, thus lowering of the incidence of mild intellectual disability.

would have been called mentally retarded. Careful attention to the pattern of delayed language and socialization skills in the presence of intact to superior nonverbal problem-solving skills should allow the identification of such children as autistic, thus lowering of the incidence of mild intellectual disability.

The effect of technologic innovations in neonatal intensive care units is twofold. First, the mortality and morbidity curves retain the same shape and magnitude but are shifted horizontally (i.e., babies who in the past would have died may now survive with handicaps, and babies who would have survived with handicaps now survive without them). Second, neonatal intensive care unit follow-up and other epidemiologic surveys all suggest a marked increase in the newer morbidity of learning and behavior disorders in children. Some of this latter increase, however, is a product of improvements in diagnostic skills, test sensitivity, and methodologic refinement on the part of the examiners. The further extension of this improved ability to discriminate the finer shades of neurobehavioral dysfunction into the area of mental retardation represents a future research direction for neurodevelopmental pediatrics.

DIAGNOSIS

The early identification of intellectual disability is the responsibility and prerogative of the pediatrician who provides well-child care. Early diagnosis is essential for successful treatment and follow-up of the child.

Screening and Early Diagnosis

Existing screening instruments are far from ideal, and the pediatric practitioner must integrate the specific tests and milestones, neurobehavioral observations, and parental concerns into a larger pattern of specific disability categories. Adequate screening cannot be defined apart from the comfort level of the physician who reaches a specific developmental diagnosis.

No ideal screening or assessment methodology exists for the office pediatrician who must work separate from a range of multidisciplinary diagnostic services. When signs and symptoms of delay were noticed in the past, they were often judged to be temporary phases. Although this occasionally may have been true, they were frequently early markers for mild neurodevelopmental dysfunction, such as the spontaneously resolving early articulation disorder that can later reappear as a reading problem. In some cases, such delays predicted more severe global intellectual disability.

The first step in the pediatric assessment of cognitive impairment is to define the child at risk. Genetic, familial, prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors that can affect the developmental rate should be documented. However, an at-risk category is distinct from a developmental diagnosis. Most at-risk children progress normally, while many older children with confirmed developmental diagnoses were never at risk. At-risk children should have their development monitored more closely, with early signs and symptoms of brain dysfunction being weighted more heavily. The treatment of undiagnosed children categorized as at risk remains problematic.

With few exceptions, motor development is relatively independent of cognitive development. Significant intellectual disability is compatible with normal motor milestones. However, cerebral palsy is associated with cognitive impairment in 50% to 75% of patients, and persons with severe intellectual disability often exhibit some degree of motor dysfunction, such as hypotonia, visual motor organization problems, clumsiness, tremor, and ataxia. Some mental retardation syndromes exhibit motor deterioration over time, as occurs early in Rett syndrome and late in cognitive impairment with autistic spectrum disorder.

The most sensitive early marker for intellectual disability is language development. Prelinguistic vocalizations in the first year of life show a clear pattern of delay even in mild cognitive impairment (Box 98.2). However, a significant disorder of language or a learning disability also may present with a distortion of early language milestones, so these delays must be supplemented by an assessment of problem-solving skills. The evaluation can range from an observational description of preferred type of interaction (i.e., 0 to 3 months, visual tracking; 3 to 6 months, reach, grasp, mouthing; 6 to 9 months, grasp, transfer, bang; 9 to 12 months, voluntary casting and release) to the use of formal assessment instruments such as the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) and the Capute Scales. The pediatrician also may use formal (Box 98.3) or informal lists of developmental milestones or maturational sequences to arrive at one or more developmental quotients (DQs), where DQ = functional age equivalent/chronological age × 100.

BOX 98.2 Clinical Linguistic and Auditory Milestones Scale*

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree