2 Menstrual problems

Premenstrual Syndrome

What is the difference between premenstrual tension, premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder?

While premenstrual tension (PMT) is the term commonly used by women to describe the constellation of symptoms some experience prior to periods, premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) are medically defined terms. Premenstrual syndrome is a diagnosis in the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). The only criterion for this diagnosis is that there should be a history of a single physical or mood symptom occurring in a cyclical basis.1 Premenstrual dysphoric disorder is a much more specific condition listed by the American Psychiatric Association in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) and supersedes the condition ‘late luteal phase dysphoric disorder’ listed in the DSM-III.2 The diagnostic criteria for PMDD are listed in Box 2.1.

What symptoms do women complain of when they have PMS?

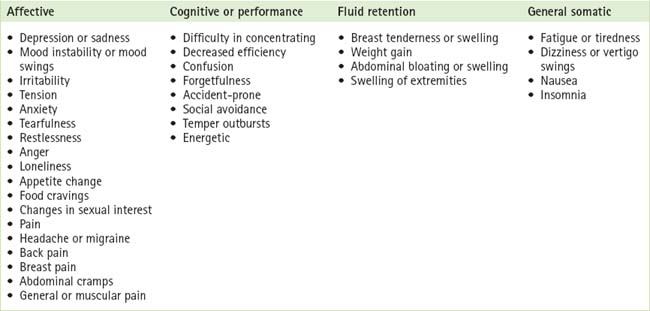

Women complain of many different kinds of symptoms when they have PMS. Premenstrual symptoms are commonly experienced as disturbances of affect, cognition and performance, and as somatic discomforts. Table 2.1 outlines the various symptoms and symptom clusters experienced. A woman tends to have the same set of symptoms from one cycle to the next.3

How common is it?

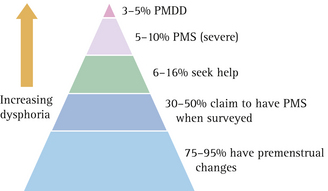

While many women complain of PMS or PMT, studies suggest that only 5–8% of women with hormonal cycles have moderate to severe symptoms.4 Premenstrual symptoms such as breast fullness and tenderness, bloating and irritability can in fact be considered as physiological, with up to 90% of women experiencing some cyclical variation in mood and physical symptoms, and 50% of women claiming to have PMS.5 Some 35% of women with the condition will seek medical treatment6 and up to 20% of all women of fertile age have premenstrual complaints that could be regarded as clinically relevant.7 A diagrammatic model that is useful in explaining this concept to patients is given in Figure 2.1.

FIGURE 2.1 A diagrammatic representation of the prevalence of premenstrual symptoms in women

(From Vanselow10)

What causes PMS?

In the past various hypotheses regarding the aetiology of PMS were upheld. These are listed in Box 2.2 (p 18). Because the symptoms of PMS are linked to the menstrual cycle, researchers believed for a long time that there must be some kind of hormonal imbalance at the root of PMS. However, multiple studies failed to demonstrate a link between PMS and circulating oestradiol or progesterone.8

The most recent theories9 suggest the following:

It is controversial whether the somatic symptoms of breast tenderness, bloating and joint and muscle pains result from a reduced tolerance to physical discomfort while in a dysphoric mood state, or are caused by changes in hormone-responsive tissues in the periphery, there being no evidence of water retention or weight gain in the premenstrual phase.4 Psychosocial factors may influence the degree to which the symptoms interfere with daily life.

Do any conditions masquerade as PMS?

PMS is probably best dealt with in the general practice context because intercurrent illness, be it psychiatric, medical or gynaecological, can contribute to premenstrual symptoms and may present as ‘PMS’. Difficulties in the social context, such as with a partner or children or at home, are probably the most common precipitating causes of presentation.10

Links have been found between PMS and sexual abuse, as well as with posttraumatic stress disorder.11 It is therefore important to identify these issues, together with any current or previous intimate partner violence. Concurrent alcohol and drug use to alleviate symptoms of depression and anxiety may also be an issue.

Research has found that a large number of women who present with symptoms of PMS do not have the condition at all. One study found that 20.5% did not have a symptom-free period in the follicular phase, 20.1% had another psychiatric condition, 16.6% had menstrual irregularities, 10.2% were menopausal or perimenopausal and 8.4% had other medical disorders.12

To produce a successful outcome, therefore, the astute practitioner needs to ensure that any comorbid conditions are detected and managed. This is particularly so because PMS may be the label a woman has given to symptoms she does not understand. One study, for example, found that the majority of women who referred themselves to a PMS clinic met the diagnostic criteria for affective disorders—most commonly major depression or anxiety disorders.13

Are there any investigations to carry out?

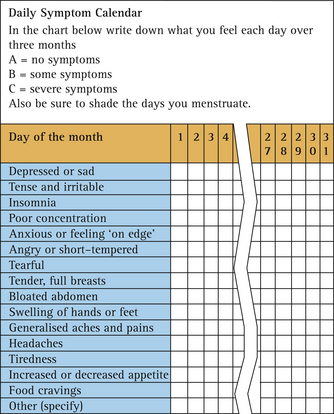

Symptom charting will help to clarify what the major symptoms are and whether they are indeed cyclical in nature. It needs to be carried out prospectively before a diagnosis of PMS or PMDD can be made. An example of a symptom chart is given in Figure 2.2.

It is important to detect and treat any underlying psychopathology. A history of mood disorder, trauma, unresolved losses or ongoing threats of harm (e.g. violence, abandonment, incarceration, homelessness, hunger or job loss) raises the likelihood of an affective diagnosis.15 Simple depression questionnaires administered premenstrually and in the follicular phase can also assist in diagnosing underlying depression.

What general approach can GPs use when managing women with PMS?

Once other pathologies have been ruled out, management can focus on the following principles:

A recurrent complaint of women with PMS is that they feel they are not believed.16 Often a sympathetic ear and a good explanation are all that is required, together with some reassurance that many women suffer from PMS to a certain degree.

A healthy lifestyle will help to overcome the condition and gain wellbeing and self-confidence. The positive effects of moderate exercise on mood and general health are well documented,17 and women engaging in moderate aerobic exercise at least three times a week have significantly fewer premenstrual symptoms than sedentary women.18,19 Learning and implementing relaxation techniques such as yoga or meditation can also be helpful because they give the patient time to herself to unwind and ‘de-stress’.20 Eating a healthy, low-fat, high-fibre diet, with adequate vitamins and minerals and reduced salt, alcohol, sugar and caffeine intake, is good general advice to give too.

Which specific treatments are effective in treating PMS?

Because SSRIs reduce both mood symptoms and somatic complaints, as well as improving quality of life and social functioning, many believe that SSRIs should be regarded as first-line treatment for PMS patients with severe mood symptoms.21 The most recent Cochrane systematic review confirms that SSRIs are highly effective in treating physical, functional and behavioural symptoms.22 All SSRIs (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine, citalopram) are effective in reducing premenstrual symptoms and can be prescribed as either luteal phase only (intermittent) or by continuous administration.22

When counselling women regarding the use of SSRIs in the management of PMDD, it is important to cover the points listed in Box 2.3.

BOX 2.3 Prescribing advice regarding use of SSRIs to treat moderate–severe premenstrual symptoms

(From Yonkers et al4)

Because, until recently, the aetiology of PMS has been so unclear, all kinds of other therapies have been promoted as cures for PMS. Despite the publication of systematic reviews of the evidence behind these ‘cures’, 24–26 women continue to use unproven treatments, often on prescription or the recommendation of their GP.

A systematic review of randomised, controlled trials (RCTs) of complementary and alternative therapies for PMS24 reviewed the evidence for the therapies shown in Box 2.4. Disappointingly, the authors concluded that on the basis of current evidence, none of the complementary/alternative therapies listed could be recommended as a treatment for premenstrual syndrome.

In a review of the efficacy of progesterone and progestogens in the management of PMS,26 its authors found no evidence to support the claimed efficacy of progesterone in the management of premenstrual syndrome and insufficient evidence to make a definitive statement about progestogens (current evidence suggesting that they are not likely to be effective).

Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) is a cofactor in neurotransmitter synthesis and is therefore thought to behelpful in treating mood-related disorders. A systematic review by Wyatt et al25 concluded that randomised, placebo-controlled studies of vitamin B6 treatment for premenstrual symptoms were of insufficient quality to draw definitive conclusions. There was limited evidence to suggest that a dose of 100 mg of vitamin B6 daily (and possibly 50 mg) is likely to be beneficial in the management of premenstrual syndrome. In particular, vitamin B6 was significantly better than a placebo in relieving overall premenstrual symptoms and depression associated with premenstrual syndrome, but the response was not dose-dependent. Importantly, no conclusive evidence was found of neurological side effects with these doses.

Evening primrose oil, another very popular therapy among women, contains the essential fatty acids linoleic and gammalinolenic acid. These are precursors of prostaglandins. Most women use evening primrose oil in an attempt to alleviate premenstrual breast symptoms. Large quantities are recommended in the order of eight 500 mg capsules a day. A review of RCTs that compared evening primrose oil with a placebo failed to show any significant benefit.27

Another option is to totally suppress ovulation in an effort to alleviate premenstrual emotional and physical symptoms. However, the use of medications such as the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonists leads to prolonged low oestrogen levels and cardiac and osteoporotic health risks. When using this medication, women will experience hot flushes and sweats, but these may be preferable to the cyclical depression, irritability and headaches of PMS. Add-back hormone replacement therapy (HRT), in which women take oestrogen in order to overcome the oestrogen-lowering side effect of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone, may be required. Danazol can also be used to treat PMS, acting by inhibiting pituitary gonadotrophins, but its side effects include androgenic and virilising effects. When used only during the luteal phase, side effects are minimised. However, while mastalgia may be relieved, the general symptoms of PMS are not.28

The humble oral contraceptive pill (COCP) can also suppress ovulation and so should theoretically improve PMS. However placebo-controlled studies have been few and mostly negative.4 A recent Cochrane review found that the new 24-day drospirenone plus EE 20 mcg COCP may help to treat premenstrual symptoms, but studies showed a large placebo effect. Further studies are necessary to clarify whether the COCP works beyond three cycles for women with less severe symptoms, and whether the drospirenone COCP is better than other COCPs in treating premenstrual symptoms.29

For specific symptom control, bromocriptine is effective in alleviating cyclical mastalgia.30

An option for patients who have expectations of negative symptoms or of impaired performance around the menses is cognitive behavioural therapy.31

Summary of key points

Secondary Amenorrhoea

What is secondary amenorrhoea?

Secondary amenorrhoea is defined as the absence of menstruation for 6 consecutive months in a woman who previously had regular periods.32 It does not include the physiological causes of amenorrhoea—namely pregnancy, lactation and menopause.

How is secondary amenorrhoea different from primary amenorrhoea?

Primary amenorrhoea occurs when there is failure to establish menstruation and is generally regarded as abnormal by the age of 14 years in girls without signs of secondary sexual development or by the age of 16 in the presence of normal secondary sexual characteristics.33 (For further information on primary amenorrhoea, see Chapter 1.)

How common is secondary amenorrhoea?

In general, secondary amenorrhoea (prevalence of 1–3%)34 is much more common than primary amenorrhoea (prevalence of about 0.3%).35 However, when considering certain population groups, such as the infertile (10–20%),36 competitive runners training 130 kilometres per week (up to 50%)32 and ballet dancers (up to 44%),32 the prevalence of amenorrhoea is much higher.

What are the common causes of secondary amenorrhoea seen in general practice?

From a clinical perspective, GPs should firstly rule out the possibility of pregnancy and ensure that it is secondary amenorrhoea and not primary amenorrhoea that they are dealing with. The majority of cases are then accounted for by one of four conditions: polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), hypothalamic amenorrhoea, hyperprolactinaemia or ovarian failure.37

PCOS is present in approximately 30% of women with amenorrhoea38 but is of itself more likely to cause oligomenorrhoea (76%) than amenorrhoea (24%).39

Up to one-third of cases of secondary amenorrhoea are caused by a prolactin-secreting adenoma.40 In women with amenorrhoea associated with hyperprolactinaemia, the main symptoms are usually those of oestrogen deficiency.41 Galactorrhoea is found only in up to one-third of hyperprolactinaemic patients, although its appearance is not correlated either with prolactin levels or with the presence of a tumour.42

Ovarian failure or menopause is considered premature if it occurs before the age of 40. In 20–40% of cases it is caused by autoantibodies;43,44 however, other causes include mumps, surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

In order to sustain a normal menstrual cycle, a woman’s body mass index needs to be >19 (normal = 20–25 kg/m2).32 Amenorrhoea is induced when a woman loses 10–15% of her normal weight for height.32 This weight loss can be due to a number of causes, from illness to anorexia to exercise. Exercise-induced amenorrhoea is found in women undertaking endurance events, such as long-distance running, and in those who participate in activities where appearance is important, such as ballet and gymnastics.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree