14 Menopause and osteoporosis

Features of the Menopause

What exactly is the menopause?

Menopause by definition is the time of cessation of menstruation. Women are said to be postmenopausal after 1 year of amenorrhoea. This occurs on average at 51.4 years1; in smokers, those with a hysterectomy and chronic disease, however, it occurs earlier.2 The perimenopause refers to those years leading up to and including the menopause. Premature menopause (that which occurs before the age of 40) occurs in up to 2.5% of women.3 It is usually iatrogenic, coming about as a result of bilateral oophorectomy, radiation or chemotherapy.

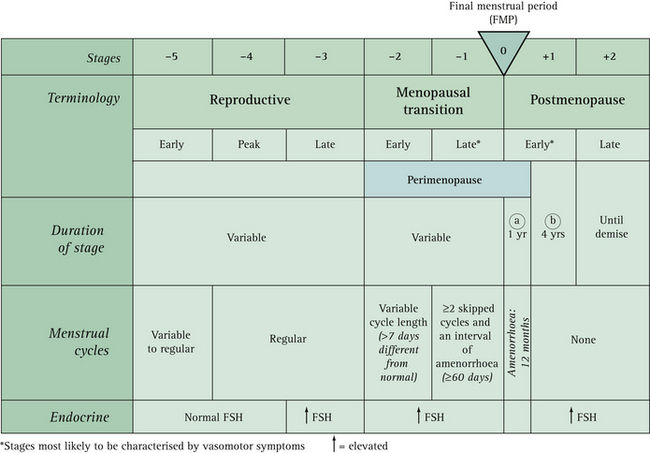

The current nomenclature used to describe stages of reproductive aging4 is described in Box 14.1 and shown in Figure 14.1.

From just after menarche (stage –5) cycles can be irregular for several years, but should then occur every 21 to 35 days for a number of years (stages –4 and –3). In the early menopausal transition (stage 2), the menstrual cycle remains regular but the length changes by 7 days or more (regular cycles are now every 24 instead of 31 days). The late menopausal transition (stage +1) is characterised by two or more skipped menstrual cycles and at least one intermenstrual interval of 60 days or more.4

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels gradually increase throughout the menopausal transition, but the variability is high and an FSH level of 40 IU/L or more is not necessarily as predictive of the late menopausal transition as amenorrhoea of 60 days or more.5

How can women tell if the menopause is imminent?

The dominant feature of the early menopausal transition is cycle length variability of 7 days or more, with cycle irregularity marking for most women the approach of their final menstrual period. The time when a woman is most likely to experience menopausal symptoms is during the late menopausal transition when there is amenorrhoea of 60 days or more. An indicator of the approach of menopause (less than 20 cycles remaining) is a rise in cycle length to 42 days or greater.6 Bleeding patterns are most indicative sign of menopausal stage, not necessarily hot flushes.5

Are there any investigations that can be used to determine whether menopause has occurred?

In women still experiencing menstrual bleeding, FSH levels measured on day 2 or day 3 after the onset of bleeding are considered increased when they exceed 10–12 IU/L, which is an indication of diminished ovarian response.7 FSH levels over 40 IU/L are indicative of the late menopausal transition.5 However, studies show that a single FSH determination alone poorly predicts menopausal status and cannot be used to predict final menstrual period.8 It has been common practice to consider ovarian failure highly likely when two measurements of FSH >30 IU/L are obtained at least 1 or 2 months apart. FSH should be measured when the woman is not taking either HT or hormonal contraception.

What are the true signs and symptoms of the menopause?

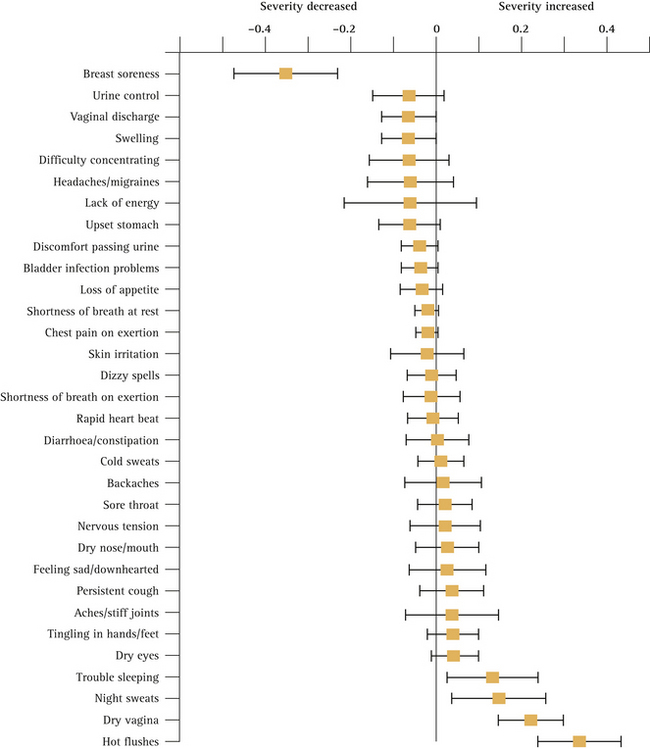

Despite the fact that all women pass through the menopause if they live long enough, the symptoms directly attributable to the menopausal transition are difficult to quantify because of confounding factors such as age, social class and education. One study9 found that vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats), difficulty falling asleep, decreased sexual interest and vaginal dryness are all associated with menopause after controlling for the effects of age. Sexual satisfaction, however, was not related to menopausal status and symptoms often associated with menopause, such as cognitive difficulties, depression and irritability, were more strongly associated with social class and employment. Dennerstein et al10 found that from early to late perimenopause increasing numbers of women reported five or more symptoms (+14%), hot flushes (+27%), night sweats (+17%) and vaginal dryness (+17%). Breast soreness/tenderness decreased with the menopausal transition (–21%). Figure 14.2 (p 258) illustrates the association between hormone status and symptoms in the women they studied. A list of the common signs and symptoms associated with menopause is given in Box 14.2 (p 259).

FIGURE 14.2 Geometric means (± 95% confidence interval) of hormone levels by menopausal status

(From Dennerstein et al10)

BOX 14.2 Signs and symptoms commonly attributed to the menopause

Another important point to note about menopausal symptoms is that, while a large proportion of women may experience menopausal symptoms, the proportion of women who experience the symptom as a problem is much less. For example, a British study11 found that 57% of women experienced hot flushes but only 22% said they were a problem, 66% reported sleep problems but only 33% said this was a problem. Interestingly, only 10% of women seek help from healthcare providers.12

How long do menopausal symptoms usually last?

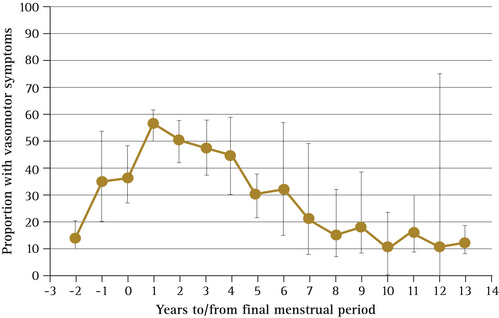

For most women, symptoms are transient, with 30–50% of women improving within several months. Hot flushes usually last for 4–5 years and in some women may take longer to resolve. A recent meta-analysis has shown peak vasomotor symptom prevalence at 1 year after the final menstrual period, with 50% of women reporting symptoms after 4 years and 10% reporting symptoms as long as 12 years later13 (Fig 14.3).

What are the long-term health implications of the menopause?

Osteoporosis, urogenital atrophy, cardiovascular disease and stroke all increase in incidence in women after menopause. While twice as many women as men suffer from Alzheimer’s disease (the most common cause of dementia among the elderly), this may in part be due to longer life expectancy.14 Interestingly, limited clinical trial evidence suggests that HT does not improve symptoms or slow disease progression in Alzheimer’s disease and that it may actually increase dementia risk when initiated after age 64 years.15,16,17 Observational studies suggest that HT used by younger women around the time of menopause is associated with lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease. However, further research is needed to determine whether there might exist an early window during which HT effects on Alzheimer’s disease risk are beneficial rather than harmful.

Hormone Therapy (HT)

What has been the uptake and usage of HT by women in recent times?

CASE STUDY: ‘Should I take hormones if I have a family history of breast cancer?’

Today, she presented wanting to discontinue her ET. After taking a history, an examination was undertaken, which was normal. Marion’s case highlights some of the complexities of giving advice about ET or HT use. Given her family history, she is right to be cautious, but the oestrogen-only arm of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study found no increased risk of breast cancer after 7 years of use compared to the oestrogen/progestogen arm of the study.18 The only two reasons to be on HT/ET are for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and the prevention of osteoporosis. While Marion is not at increased risk of the latter, some women continue to have hot flushes for many years after the menopause. In about 1 in 10 women who discontinue hormone therapy, the recurrence of menopausal symptoms is severe and persistent.19 Marion could try again to come off the ET; if this were not tolerated, other treatments for vasomotor symptoms could be offered such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (e.g. venlafaxine or paroxetine) or clonidine.

by pharmaceutical companies to prescribe HT as both a therapeutic and preventive agent, as the potential market for HT is enormous (all women over 45).

Despite this, it is interesting to note that less than 20% of population samples of postmenopausal women in the USA have ever had HT prescribed. In addition, less than 40% of women who commence HT are still using it 1 year later,20 and after 3 years that percentage drops further to 25%.21 The reasons for this poor compliance may be related to the side effects that women experience when they use HT, such as bloating, breast tenderness and withdrawal bleeds, or to the perceived risks, especially breast cancer.

Up until 2002, when the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study results were publicised,22 use of HT in postmenopausal women varied from <10% in the UK, to 30–40% in the US. Australia was slightly less than the US with 28% of postmenopausal women taking HT and 12–22% throughout Europe.23 In Australia, prescriptions for oestrogen/medroxyprogesterone acetate fixed-dose preparations dropped by 55.4% in the following 12 months; uptake of HT preparations decreased by about 30% in the same period and continued to fall at a lower rate following publication of the oestrogen-only (9%) and memory arms of the WHI (4%).24

What advice should general practitioners give patients seeking information about the pros and cons of HT?

In recent years, controversy has raged over the indications for HT and the risks and benefits of using HT in peri- and postmenopausal women. Much of this controversy stems from the undue fears and confusion that have resulted from the misinterpretation of clinical studies and the overrepresentation of risks arising from these studies,25 in particular:

In counselling women about HT, it is essential that GPs are skilled in representing risk accurately (Box 14.3). Common non-cancer risks and benefits are outlined in Table 14.1.

BOX 14.3 Understanding terminology associated with risk (the possibility or chance of harm)

From North America Menopause society18)

Relative risk (RR)

TABLE 14.1 The benefits and harms of using HT for 1 year in 10,000 women aged 65–74 years

| Consequences | Number of cases | |

|---|---|---|

| Benefits (events prevented) | ||

| Harms (events caused) | ||

(From Nelson et al82)

Practice tips

Consider the following when explaining and presenting risk to patients18:

Guideline recommendations

The following is a summary of the NAMS position statement on HT18 and represents current guidelines on HT use.

Vasomotor symptoms

HT is the most effective treatment for hot flushes and night sweats. These symptoms remain the primary indication for HT.

Diabetes mellitus (DM, or type 2 diabetes)

DM is not a contraindication for HT. Limited evidence suggests that HT may actually reduce the incidence of DM in the order of 15 per 10,000 women per year of therapy, but this is not a reason in itself to prescribe. When prescribing oestrogen for a woman with DM, non-oral preparations may be preferred because of their reduced impact on raising triglycerides.

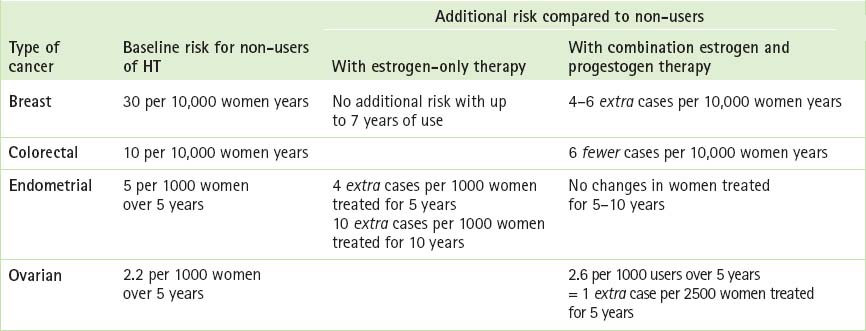

Breast cancer

Table 14.2 describes cancer risks and benefits associated with HT and may be helpful when counselling patients. Box 14.4 (p 264) contains the current recommendations of the National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre (NBOCC) regarding breast cancer risks and hormone therapy.28

BOX 14.4 Recommendations regarding HRT and breast cancer risk

Women with no personal or family history of breast cancer

Women with a personal or family history of breast cancer

Cognitive ageing/decline and dementia

HT cannot be recommended at any age for the sole purpose of preventing cognitive ageing or dementia. The WHIMS study16 showed an increase in dementia when HT was initiated in women over 65. Available data do not currently address whether HT used soon after the onset of menopause increases or decreases later dementia risk.29

Summary of key points

Practical therapeutic issues

Progestogen indication

Progestogen is indicated to safeguard the endometrium. Given the evidence suggesting that progestogen added to oestrogen increases breast cancer risk, cardiovascular risk and adverse symptoms, it would obviously be best to reduce exposure to the least amount necessary in order to protect the endometrium.

Regimens

Research findings are inadequate to favour one regimen of dosing over another. There is insufficient evidence regarding endometrial safety to recommend as an alternative to standard EPT regimens the off-label use of: long-cycle regimens (14 days of progestogen every 2–6 months), vaginal administration of progestogen, the Mirena or low-dose oestrogen without progestogen. If any of these regimens are used, close surveillance is warranted. For a definition of the different EPT regimens, see Table 14.3.

TABLE 14.3 Terminology defining some types of EPT regimens

| Regimen | Oestrogen | Progestogen |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclic | Day 1–25 | Last 10–14 days of ET cycle |

| Cyclic combined | Day 1–25 | Day 1–25 |

| Continuous—sequential | Daily | 10–14 days every month |

| Long cycle | Daily | 14 days every 2–6 months |

| Continuous—combined | Daily | Daily |

| Continuous—pulsed | Daily | Repeated cycles of 3 days on and 3 days off |

(From North American Menopause Society18)

Duration of use

When started in close proximity to menopause, the only long-term risk (beyond 5 years) might be an increased risk of breast cancer. Women who have reasons to remain on HT must have regular and appropriate follow-up, including mammography. As stated by the North American Menopause Spciety (NAMS),18 provided that a woman is on the lowest effective dose, is well aware of the potential benefits and risks and has clinical supervision, extending HT use for individual treatment goals is acceptable under some circumstances for:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree