12.3 Meningitis and encephalitis

Bacterial meningitis

Human genetic factors

• Defects in the various complement pathways predispose to meningococcal disease. First recognized were mutations of terminal complement components, then properdin.

• More recently, variants in mannose-binding protein and factor H binding protein have been identified as increasing the risk of meningococcal infection.

• For Hib, genetic variation in Toll-like receptor-4 and associated pathways are linked to increased risk.

• The risk of pneumococcal disease is increased by an inherited defect in interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-4 (IRAK-4), leading to a failure to make cytokines following stimulation with Toll-like receptor agonists such as interleukin-1β.

• Congenital absence of the spleen may have a genetic basis and predisposes to infection with encapsulated organisms.

• Immunoglobulin deficiencies (X-linked or recessive) predispose to meningitis generally, whereas recurrent meningococcal disease may be associated with immunoglobulin (Ig) M deficiency.

Other factors that increase the risk of meningitis:

• Acquired impaired immunity (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus infection) and splenectomy

• Congenital or acquired neuroanatomical defects (e.g. base of skull fracture)

• Penetrating head injuries, neurosurgical procedures

• Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak

• Congenital dural defect (dermal sinus or myelomeningocele)

Aetiology

The most common pathogens in each age group are:

Pathogenesis

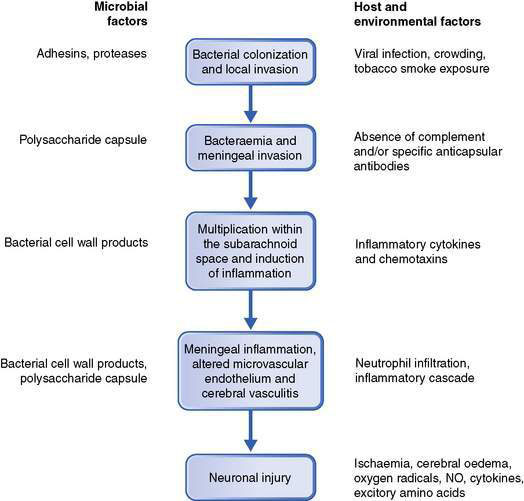

The development of bacterial meningitis usually follows: (1) colonization of the nasopharynx by encapsulated bacteria; (2) invasion of the host causing bacteraemia and then invasion of the meninges; (3) bacterial multiplication and induction of inflammation within the subarachnoid space; and (4) neuronal injury (Fig. 12.3.1).

Clinical presentations

Children aged at least 3 years

Symptoms and signs are more obvious:

• severe headache, vomiting, photophobia

• fever, neck stiffness, delirium or deteriorating consciousness.

Convulsions are a presenting feature in 20–30% of infants and children with bacterial meningitis. Those with meningococcal meningitis or septicaemia may have a petechial and/or purpuric rash over the trunk, limbs and, in extremis, the face. Initially the rash may be blanching, but within hours become non-blanching purpuric lesions that may progress through dermal vascular necrosis to peripheral gangrene (Fig. 12.3.2).

Diagnosis

Paired serology is helpful, but only in retrospect.

• Needle aspirate from skin lesions for Gram stain and culture is useful for diagnosis in meningococcal disease.

• Suprapubic aspirate or catheter urine specimen, if less than 6 months old, may reveal dual sites of infection.

• Full blood count, including white blood cell differential, C-reactive protein or procalcitonin may all point to the seriousness of infection.

• Serum electrolytes, glucose and creatinine should be monitored and managed.

Lumbar puncture is delayed for patients with any of the following:

• absent or non-purposeful responses to pain

• focal neurological signs (or a false localizing sixth nerve palsy)

• abnormal pupil size or reaction

• decerebrate or decorticate posturing

• irregular breathing, rising blood pressure and falling pulse (despite peripheral vasoconstriction)

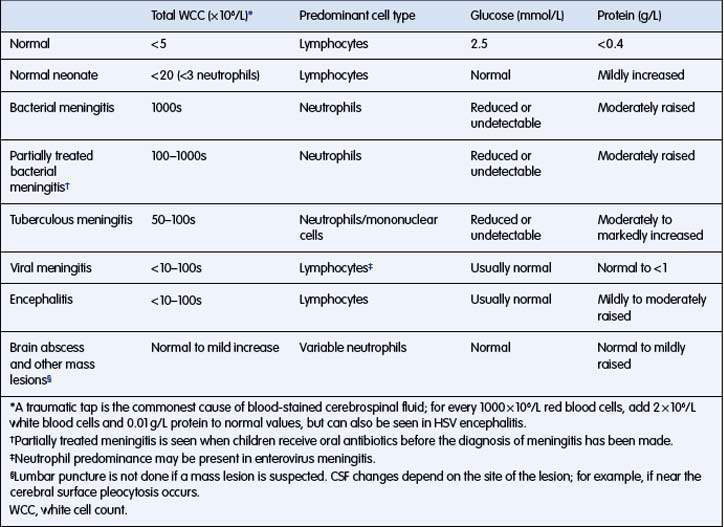

The typical CSF changes in bacterial meningitis are outlined in Table 12.3.1. Organisms are often seen on Gram stain of the CSF, making a presumptive diagnosis possible.

CSF examination may be difficult to interpret, especially when prior antibiotics have been given.

Antibiotic treatment

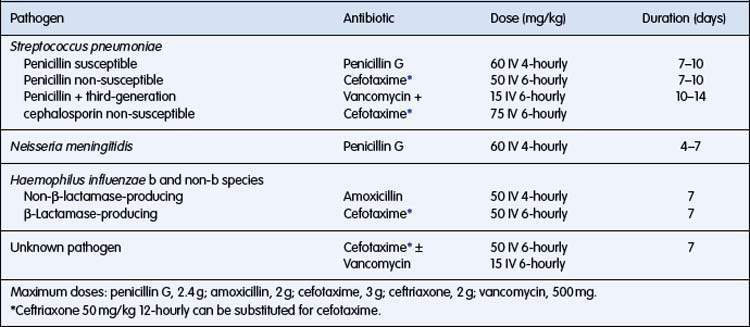

Subsequent adjustments depend on culture and sensitivity results.

Dosage and duration of antibiotic treatment are outlined in Table 12.3.2.