Fig. 29.1

Melanoma of the scalp in a 5-year-old girl

However, the presentation of pediatric melanoma can be nonspecific, mimicking a benign or dysplastic nevus, a hemangioma, a Spitz nevus, a pyogenic granuloma, or a verruca. Also importantly, compared with adult melanoma, pediatric melanoma is often amelanotic or raised [12], and often the above symptoms are absent [13].

Seven percent of melanomas that develop in an existing nevus are asymptomatic [14].

The scalp and neck are the most common head and neck areas involved [15], although other tissues, including the mucus membranes or eyes, can be involved.

Patterns of Evolution

The low incidence and differences in presentations from adult disease make pediatric melanoma difficult to diagnose and may result in late diagnosis and increased mortality in up to two-thirds of cases [16].

Evaluation at Presentation

After complete characterization of the lesion by exam, punch biopsy should be performed. Punch biopsy is considered superior to shave biopsy because it offers more information on depth of invasion [13].

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of melanoma is wide (Table 29.1), and thus proper referral and early biopsy should be done when melanoma is suspected. In early childhood, the diagnosis of Spitz nevus (also called spindle cell nevus or benign juvenile melanoma) should be considered. This entity usually presents during childhood, as uniformly pink, tan, or red-brown dome-shaped papules or nodules, in the face or lower extremities. Spitz nevus is usually well circumscribed and small (< 1 cm).

Table 29.1

Differential diagnosis of melanoma

Spitz nevus |

Traumatized common congenital/acquired nevus |

Pyogenic granuloma |

Dysplastic nevus |

Traumatized verrucae |

Blue nevi |

Hemangioma |

Angiokeratoma |

Thrombosed lymphangioma |

Keloid |

Seborrheic keratosis |

Pigmented basal cell carcinoma |

Diagnosis and Evaluation

Physical Examination

The physical exam diagnostic criteria are similar to those used in adults:

Size greater than 10 mm

Inconsistent color

Asymmetry

Poorly demarcated borders

Ulceration

It should be noted, however, that some pediatric melanomas will not meet any of these criteria, so consideration of the diagnosis in other lesions is crucial for timely diagnosis.

Laboratory Data

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is well-tolerated and indicated for all melanomas greater than 1 mm thick, those with ulceration or Clark level III or IV, or with aggressive or uncertain pathology. If positive, a complete lymph node dissection should be undertaken [5]; if negative, patients are saved the morbidity of the complete dissection .

SLN biopsy should include injection of both blue dye and radionucleotide lymphoscintigraphy to increase accuracy of sentinel node identification, especially in the head and neck, where there is great variability of lymphatic drainage. This procedure led to clearly identifiable SLNs in a series of seven pediatric head and neck melanoma cases, with excellent correlation between the two markers.

SLN biopsy was definitive in differentiating melanoma from a benign lesion in this same case series [17], which can be difficult in children [18]. Results from this series also suggested that likelihood of positive sentinel node increased with primary lesion thickness, just as in adults [17].

SLNs should be examined by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining; if this is negative for melanoma, immunohistochemistry should be performed for melanoma-specific antigens.

Imaging Evaluation

Imaging studies are usually recommended when nodal involvement is present. This should include imaging of the region to evaluate for nodal disease, as well as metastatic workup to evaluate for liver and lung involvement (Fig. 29.2). Although there are little data in children, PET imaging has been shown to be useful in the metastatic evaluation of adults with cutaneous melanoma, leading to a change in management in 35 % of patients and allowing a higher sensitivity than CT for occult metastases [19].

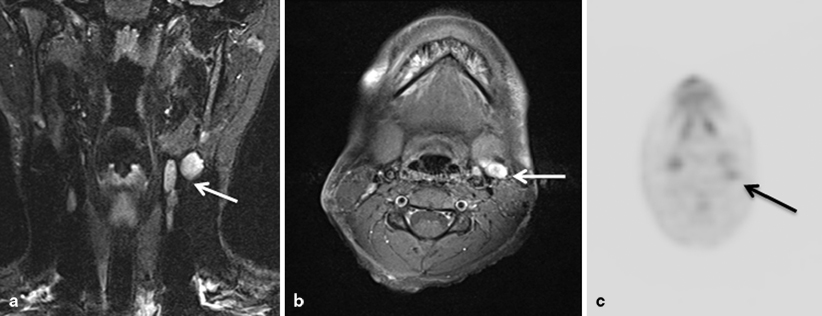

Fig. 29.2

Coronal (a) and axial (b) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images of the head and neck in a child with melanoma of the scalp showing multiple enlarged lymph nodes (arrow). Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) of the same patient shows FDG update in the involved nodes (arrow) (c)

Pathology

On microscopic examination, the following features are suggestive of malignancy, though no one factor alone is diagnostic: prominent intraepidermal pagetoid of single cell spread, irregular intraepidermal tumor nests formation, atrophy or ulceration of the epidermis, extension into the dermis or subcutaneous tissue, expansive deep border, cellular atypia, deep or atypical mitoses, and absence of maturation [20]. Superficial spreading melanoma is easily the most common subtype in children, with the nodular subtype second. The lentigo maligna subtype, common in adults, appears to be very rare in pediatrics [15]. Amelanotic disease is more common than in adults [5]. Spitzoid melanoma and nevoid melanoma often appear different pathologically and require awareness of these diagnoses to differentiate them from benign conditions. In the case of Spitz nevus, immunohistochemistry for HMB-45 and Ki-67 can help differentiate the condition from spitzoid melanoma. Mucosal melanoma is very rare and generally resembles cutaneous melanoma microscopically. About two-thirds of patients with Clark level IV–V or Breslow thickness greater than 1.5 mm have nodal disease, whereas nodal spread is unusual in thinner lesions [1]. The most common cytologic appearance and immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma are shown in Fig. 29.3.

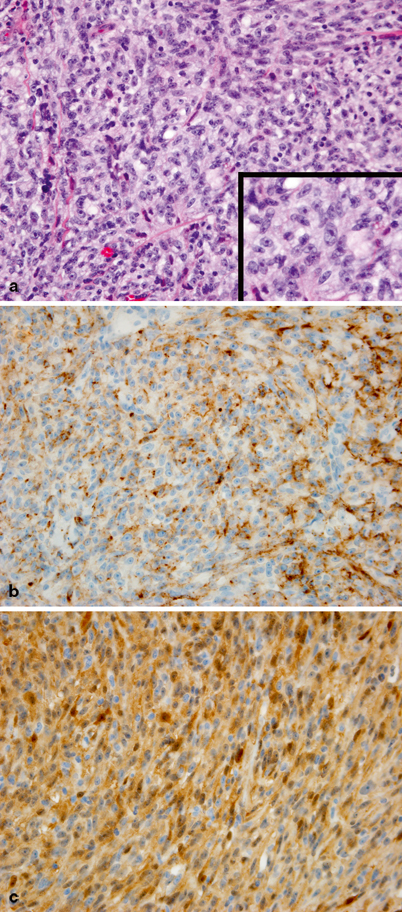

Fig. 29.3

a Undifferentiated tumor cells with a solid and vaguely nesting pattern of growth. Tumor cells have spindled and epithelioid morphology with large nuclei and prominent single, centrally located, eosinophilic nucleoli. Inset at higher magnification. b Tumor cells are diffusely immunoreactive for HMB45. c Strong immunoreactivity for S100 protein is also observed

Treatment

Surgical excision is the cornerstone of treatment of melanoma in children. For patients with high risk of recurrence, including those with thick lesions and/or nodal spread, adjuvant treatment with high-dose interferon (IFN) is becoming the standard of care .

IFN α2b is recommended as an adjuvant therapy for high-risk melanoma (thickness greater than 4 mm or presence of nodal disease) in adults [21]; in general, an intense induction month is followed by several months of lower-dose maintenance treatment. Children tolerate the treatment better than adults do [22]; the most common side effects are anxiety, agitation, and depression [13]. The efficacy in pediatrics, however, is unclear.

For patients with unresectable, metastatic, or recurrent melanoma, systemic therapy is indicated. Standard chemotherapy has limited effect; DTIC, temozolomide, and taxanes are the most active agents, but responses are seen in only 20–30 % of patients, and usually do not last more than 4–6 months. High-dose IL-2 has also shown to be effective, and combinations of IL-2 with chemotherapy are often used.

Melanoma is a very immunogenic neoplasm; in addition to IFN and IL-2, other immunological approaches have shown remarkable results for patients with advanced disease in recent years. Recently, the anti-CTLA4 monoclonal antibody ipilimumab demonstrated survival prolongation of several months in recurrent advanced melanoma [23]. In addition, treatment with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes achieved a durable remission over years in a substantial minority of patients with metastatic, mostly refractory disease [24].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree