Medication Errors

John Chuo

George Lambert

Definitions

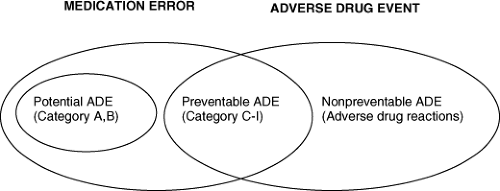

A medication error is defined as the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of the wrong plan to achieve a specific aim (1). A medication error is such an error that occurs during the medication use process (2). Essentially, the right drug must be given to the right patient, in the right route, at the right dose, and at the right time (five rights) (3). Figure 60.1 illustrates the relationship among medication errors and potential, preventable, or unpreventable adverse drug events (ADEs) (4,5). ADEs are any injury due to medications (2). Preventable ADEs are medication errors that harm patients, whereas unpreventable ones are considered adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and not errors. Potential ADEs are errors that do not harm patients. A potentially harmful medication error (potential ADE) that is identified and corrected prior to drug administration is classified as a near miss, and a nonintercepted potential ADE that by chance does not result in patient injury is classified as a no-harm event. Errors can be acts of commission or omission. The authors of this chapter would like to call attention to a third error type—propagation errors—acts that permit errors committed at an earlier use process stage to pass on to the next stage or reach the patients.

Introduction

Medication errors exact a high toll on patient safety and health care costs, resulting in approximately 7,000 deaths per year (6). In the hospital setting, where most of the reports have been generated, approximately 47% of medical errors are medication related (6). Kaushal et al. reported that ADEs occur at 2.3 per pediatric admissions and approximately 19% of them are preventable (7). The 2007 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on prevention of medication error estimates that a hospital patient may be subjected to at least one medication error per day (6). In terms of ADEs, at least 1.5 million occur each year in the United States: 380,000 to 450,000 in hospital care, 800,000 in long-term care, and 530,000 in ambulatory care. The financial burden is significant. Each medical error adds approximately 4.6 days to hospitalization and $5,857 to the patient care cost (8).

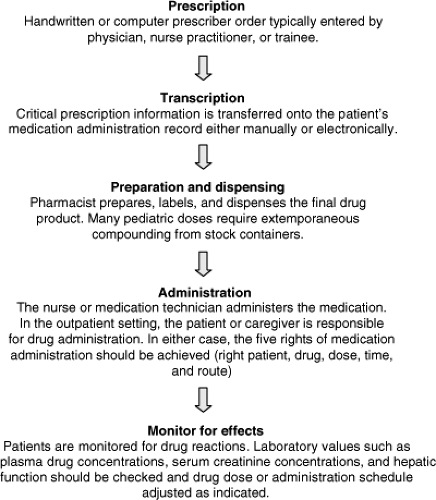

Medication errors are preventable mishaps occurring during any step of the drug use process that can lead to inappropriate drug use and patient harm (9). The opportunities for error are staggering when one considers that hundreds of medication orders are prescribed each day in larger neonatal units. Each medication use process has five steps beginning with conception to prescription, transcription dispensing, administration, and ends with effects monitoring (Fig. 60.2); each step has subprocesses that must get all five rights correct. In total, a single antibiotic order will have at least a dozen error opportunities, assuming that no process variations exist. However, medication use processes operate frequently in the midst of certain barriers that will, no doubt, produce process variation and greatly increase error opportunities. For example, distractions may cause a physician to prescribe the wrong dose; a ward clerk, nurse, or pharmacist to transcribe a written prescription incorrectly onto the pharmacy’s queue; the pharmacist to make a calculation error or dispense the wrong medication; or the patient’s nurse to administer the drug to the wrong patient or to the right patient at the wrong time. In the outpatient setting the patient’s parent or caregiver may measure the dose incorrectly. Finally, in a patient with renal disease, the patient may start therapy with the correct drug and dose, but inadequate monitoring of serum creatinine concentrations could subsequently prevent the necessary dosage adjustment should renal function decline. Most errors fall into the commission category in which the correct medication plan is executed incorrectly. Omission errors are those in which the wrong medication plan (including no treatment) is executed. Propagation errors are “passive” in the sense that the usual safeguards (i.e., five rights checklist) are not used to stop an error committed earlier in the use process from reaching the patient. Workflows producing these errors involve complex human and environmental factors. The IOM report “To Err Is Human,” attributes most patient injuries not to culpable individuals, but systemic factors such as poor communication systems, and unrealistic dependency on human memory and vigilance (1).

Prevention can happen at many levels. The IOM report summarizes patient-centered patient safety support at four levels—the federal, institution, unit, and patient. Ideally, support at each level would operationally complement one another. For example, the state of Pennsylvania mandates

QI reporting, the institution builds reporting infrastructure that is user-friendly and establishes a “nonblame” culture, the unit ward develops communication and educational forums that leverage the staff’s expertise to identify systemic improvements (which will feedback to the institution), and the patient and family become an active part of the care team.

QI reporting, the institution builds reporting infrastructure that is user-friendly and establishes a “nonblame” culture, the unit ward develops communication and educational forums that leverage the staff’s expertise to identify systemic improvements (which will feedback to the institution), and the patient and family become an active part of the care team.

Frequency of Medication Errors

Reports on medication error rates vary widely depending on the reporting mechanism (10,11,12,13,14). Somewhat structured written “incident reports” are most commonly used through a voluntary reporting system. Significant underreporting exists, especially for near misses. This is partly due to a hesitancy to report errors given the traditional approach to medication error management of blaming the responsible individual(s) rather than focusing on correcting a flaw in the medication delivery system that allowed the error to occur. The IOM committee, in its “Preventing Medication Errors” publication, comments that the reports of about 400,000 preventable ADE annually are likely to be underestimates. Detection methods include review of written orders, prompted reporting, chart review, electronic record extraction, and direct participation in clinical care (6). Jha et al. emphasized the complementary effect of using three methods, computerized surveillance of medical records, chart review, and voluntary reporting, together to find errors (15). Recently, trigger-based detection methods, such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement global trigger tool, have been shown to be effective in identifying error clues in retrospective chart reviews (16). Its success has prompted adapting its use for other medical errors in clinical care.

When studying and comparing medication error rates, it is critical to remember that the denominator may change the rate value significantly (17). For example, prescribing errors have ranged from 12.3 to 1,400 per 1,000 admissions, 0.61 to 53 per 1,000 orders, and 1.5 to 9.9 per 100 error opportunities (2,18,19,20,21,22,23). Preventable ADE rates per 1,000 admission range from 3.7 to 84.1 (24,25,26). Preparation and dispensing error rates are reported to be 2.6 per 1,000 admissions in general and 26% to 49% per preparation for intravenous medications (23,27,28). Errors in adults and pediatrics are approximately equal (29,30,31,32,33,34) at about 5%.

In the ambulatory setting, it is estimated that four invalid doses per 100 immunizations are given to children, or 36% of children are being immunized at least one invalid dose during childhood (35). Overimmunization happens in approximately 21% of patients (36). In two emergency room reports, 10 and 3.9 errors per 100 patients happen in the prescribing and administering phases, respectively (37). In the hospital setting, where most of the reports have been generated, approximately 47% of medication errors are medication related.

There is controversial evidence of an alarming increase in the incidence of medication errors and related mortality in the United States since the introduction of prospective pricing by Medicare in 1983 (38,39,40,41,42). Evaluating mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) codes during the period spanning 1983 to 1998, the authors reported a 157% increase in the incidence of medication errors (38). Based on ICD-9 E850 through E858, the authors’ definitions

of medication errors involving the patient or medical staff included accidental drug overdoses, accidental administration of the wrong drug, and accidents involving the administration of drugs or biologic agents during medical or surgical procedures (39). The associated increase in patient mortality during this time period was 137% among hospitalized inpatients and 907% among outpatients (38). The authors mentioned that a number of potential factors contributing to the apparent increase in medication errors, including the increasing complexity of the health care system and the cost containment measures aimed at shortening the length of hospitalization, have increased the utilization of outpatient care and limited the time available for direct contact between patient and physician (38). It should be pointed out that the results of the study have been criticized for possibly mislabeling accidental poisoning deaths, a sizable proportion of which involved drugs of abuse, as medication errors (40,41,42). This criticism is based on the use of the term “accidental poisoning” rather than “medication error” in the ICD-9 codes, and on the characteristics associated with the patient population. For example, of the 7,391 mortalities reported in 1993, the term “drug abuse” was used in approximately 30% of cases, whereas only 0.6% to 3.4% of cases included a description of chronic illness, such as ischemic heart disease, pulmonary disease, or cancer (42).

of medication errors involving the patient or medical staff included accidental drug overdoses, accidental administration of the wrong drug, and accidents involving the administration of drugs or biologic agents during medical or surgical procedures (39). The associated increase in patient mortality during this time period was 137% among hospitalized inpatients and 907% among outpatients (38). The authors mentioned that a number of potential factors contributing to the apparent increase in medication errors, including the increasing complexity of the health care system and the cost containment measures aimed at shortening the length of hospitalization, have increased the utilization of outpatient care and limited the time available for direct contact between patient and physician (38). It should be pointed out that the results of the study have been criticized for possibly mislabeling accidental poisoning deaths, a sizable proportion of which involved drugs of abuse, as medication errors (40,41,42). This criticism is based on the use of the term “accidental poisoning” rather than “medication error” in the ICD-9 codes, and on the characteristics associated with the patient population. For example, of the 7,391 mortalities reported in 1993, the term “drug abuse” was used in approximately 30% of cases, whereas only 0.6% to 3.4% of cases included a description of chronic illness, such as ischemic heart disease, pulmonary disease, or cancer (42).

In summary, medication error rates are underreported. Reporting standards needs further specifications. Nevertheless, reported error rates are unacceptably high and can be used to track the effectiveness of medication error prevention programs and focus efforts.

Common Types of Medication Errors

It is estimated that at least 380,000 to 450,000 preventable ADEs occur in US hospitals annually (26,43). Many reported ADEs were preventable (27% to 50%) and occurred in the prescription and administration stages (39% and 38%, respectively) (44). Prescription error types were predominately wrong dose, known allergy, wrong frequency, and drug–drug interaction. In the Bates et al. study, 53% of the prescription errors were missing doses; of the remaining 250 medication errors, 31% were dose errors, 31% wrong frequency, 10% wrong route of drug administration, 6% illegible prescription handwriting, and 4% drug administration to a patient with a documented allergy to the agent, numbers that more closely resemble the percentages reported by the other studies listed in Table 60.1 (2,12,37,45,46). Leape et al. (47) analyzed 264 preventable and potential ADE events and identified the three top proximal causes of error as lack of knowledge of the drug, lack of information about the patient, and rules violations (22%, 14%, and 10%, respectively). Most errors occurred in the prescription and administration phase (39% and 38%, respectively). They found that poor access to information accounted for 78% of the errors, with the top three system failures being drug knowledge dissemination, dose and identity checking, and patient information availability (29%, 12%, and 11%, respectively). Studies also suggest that overdoses are the most common type of dosing error, with the majority of errors occurring at the drug ordering state (32,46,48). Not surprisingly the drug classes most often involved in medication errors are the ones most often prescribed to hospitalized patients (Table 60.2) (2,45,46). Antibiotics are most often associated with medication errors in the hospitalized patients, accounting for approximately 20% to 40% of all medication errors. Other drug classes commonly involved in medication errors include cardiovascular agents, gastrointestinal agents, vitamin or mineral products, electrolyte concentrates, and nonnarcotic and narcotic analgesics.

Table 60.1 Common Types of Medication Errors, as a Percentage of Total Medication Errors Identified in Each Respective Study | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Underutilization of medications (errors of omission) deserves mention and is reported mostly by the adult literature. Most studies report a wide variation in compliance with “in time treatment” of acute myocardiac infarction, antibiotic prophylaxis, and thromboembolic prophylaxis. Depending on the exact treatment (error of omission), myocardial infarction (MI) was at 51% to 93%, surgical antibiotic prophylaxis was at 70% to 98%, and thromboembolic prophylaxis was at 5% to 90% (38,39,40,41,42,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61).

Table 60.2 Drug Classes Most Often Involved in Medication Errors, as a Percentage of Total Medication Errors Identified in Each Respective Study | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree