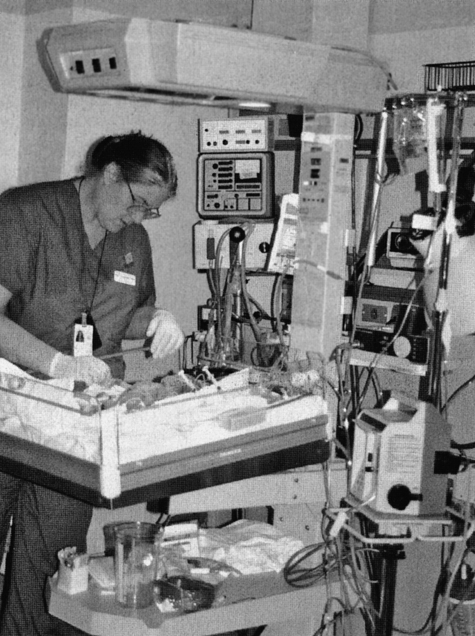

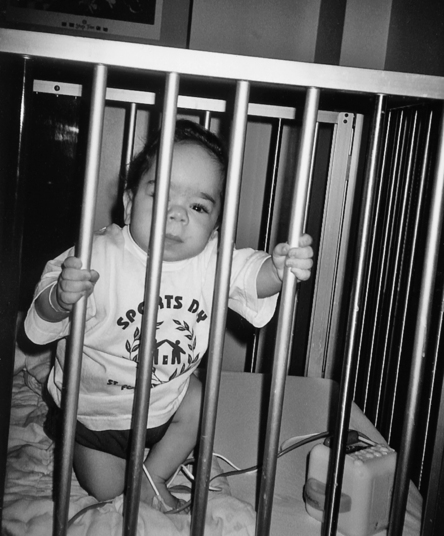

3 DAWN B. OAKLEY and KATHLEEN BAUER After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Describe occupational therapy practice in a medical system. • Identify and discuss the components (i.e., settings and key members) of a pediatric medical system. • Differentiate among pediatric acute care, subacute care, long-term care, and home care medical settings. • List five commonly assessed areas of function in a pediatric medical-based occupational therapy evaluation. • Differentiate among the multidisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and interdisciplinary styles of collaboration. • Discuss the roles of the occupational therapist and the occupational therapy assistant during the process of intervention and documentation in a pediatric medical system. • Discuss medical reimbursement issues and payment options for pediatric medical services. • Identify the important challenges faced by a medical-based pediatric OT practitioner. A medical system includes many team members, including children, families, specialists, generalists, nurses, physicians, physical therapists, child life or therapeutic activity therapists, speech and language pathologists, and occupational therapists. A pediatric medical care system comprises a group of individuals (professional, paraprofessional, and nonprofessional) who form a complex and unified whole dedicated to caring for children who are ill (Box 3-1).9 This environment may initially be overwhelming to an entry level OT practitioner. The medical team closely monitors the medical status of NICU clients. A neonatologist serves as the leader of the NICU team (Figure 3-1). In addition to conducting a neonatal assessment, the neonatologist consults with the other professionals on the medical team about the specific needs of the infant. The following conditions may indicate that an infant should be admitted to the NICU: 1. Cyanosis—an infant who turns blue because of insufficient oxygen 2. Bradycardia—a heart rate of less than 100 beats per minute (bpm) 3. Low birth weight (LBW)—a weight of less than 2500 g 4. Very low birth weight (VLBW)—a weight of less than 1500 g 5. Extremely low birth weight (ELBW)—a weight of less than 750 g When the medical team determines that the infant has met certain physiologic requirements, the infant is moved out of the NICU. If the infant still requires some form of hospital-based medical care, the infant can be transferred to a step-down nursery or pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) (Figure 3-2). In addition to continuing to address the infant’s acute symptoms, the goals of the PICU team are to attempt to wean the infant from external sources of medical support and, when applicable, provide sensorimotor stimulation. As the infant is moved from one unit to another, additional team members may be required, and the services of certain other members may no longer be needed. For example, in the PICU, the infant’s medical team leader is no longer a neonatologist; it is a pediatrician. As an infant’s condition improves, he or she may no longer require the level of care provided in a PICU; however, the infant may not yet be ready to be discharged home. In this instance, the infant may be transferred to a subacute setting (Figure 3-3). The medical needs of the infant, as well as the desires of the infant’s primary caregivers affect this decision. The goals of the subacute team are to provide appropriate medical treatment while continuing to wean the infant off medical supports and carrying out development-based therapeutic interventions. The infants receive medical care through scheduled clinic and outpatient hospital-based visits (Figure 3-4). The coordination of an infant’s nursing, therapy, and equipment needs are often transitioned to a community-based home care agency. These agencies monitor clients’ medical needs and coordinate home-based therapeutic services. The age of the client determines where the services are provided. Infants and young children usually receive home-based services. As children mature, their services may remain at home, or they may transition to an outpatient clinic or community-based early intervention (EI) or Early Head Start setting.

Medical system

Medical care settings

Neonatal intensive care unit

Pediatric intensive care unit

Subacute setting

Home

Role of occupational therapy in the pediatric medical system

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Medical system

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue