Chapter 238 Measles

Epidemiology

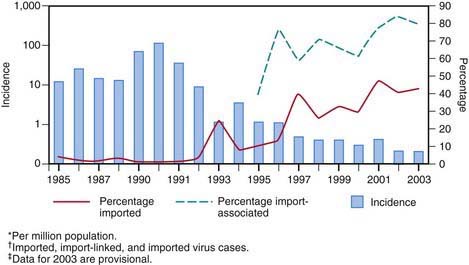

Measles continues to be imported into the USA from abroad; therefore, continued maintenance of >90% immunity through vaccination is necessary to prevent widespread outbreaks from occurring (Fig. 238-1).

Figure 238-1 Incidence* and percentage of import-associated† measles cases, by year in the USA, 1985–2003‡.

(From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Epidemiology of measles—United States, 2001–2003, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 53:713–716, 2004.)

Clinical Manifestations

Measles is a serious infection characterized by high fever, an enanthem, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and a prominent exanthem. After an incubation period of 8-12 days, the prodromal phase begins with a mild fever followed by the onset of conjunctivitis with photophobia, coryza, a prominent cough, and increasing fever. Koplik spots represent the enanthem and are the pathognomonic sign of measles, appearing 1 to 4 days prior to the onset of the rash (Fig. 238-2). They first appear as discrete red lesions with bluish white spots in the center on the inner aspects of the cheeks at the level of the premolars. They may spread to involve the lips, hard palate, and gingiva. They also may occur in conjunctival folds and in the vaginal mucosa. Koplik spots have been reported in 50-70% of measles cases but probably occur in the great majority.

Figure 238-2 Koplik spots on the buccal mucosa during the 3rd day of rash.

(From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Public health image library, image #4500 [website]. http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/details.asp.)

Symptoms increase in intensity for 2-4 days until the 1st day of the rash. The rash begins on the forehead (around the hairline), behind the ears, and on the upper neck as a red maculopapular eruption. It then spreads downward to the torso and extremities, reaching the palms and soles in up to 50% of cases. The exanthem frequently becomes confluent on the face and upper trunk (Fig. 238-3).

Figure 238-3 A child with measles displaying the characteristic red blotchy pattern on his face and body.

(From Kremer JR, Muller CP: Measles in Europe—there is room for improvement, Lancet 373:356–358, 2009.)

Differential Diagnosis

Typical measles is unlikely to be confused with other illnesses, especially if Koplik spots are observed. Measles in the later stages or inapparent or subclinical infections may be confused with a number of other exanthematous immune-mediated illnesses and infections, including rubella, adenoviruses, enteroviruses, and Epstein-Barr virus. Exanthem subitum (in infants) and erythema infectiosum (in older children) may also be confused with measles. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and group A streptococcus may also produce rashes similar to that of measles. Kawasaki syndrome can cause many of the same findings as measles but lacks discrete intraoral lesions (Koplik spots) and a severe prodromal cough, and typically leads to elevations of neutrophils and acute-phase reactants. In addition, the characteristic thrombocytosis of Kawasaki syndrome is absent in measles (Chapter 160). Drug eruptions may occasionally be mistaken for measles.