Chapter 693 Marfan Syndrome

Pathogenesis

Aberrant TGF-β signaling might also play a role in the wider spectrum of manifestations of MFS. Increased TGF-β signaling has been observed in many tissues in MFS mice, including the developing lung, skeletal muscle, mitral valve, and dura. Treatment of these mice with agents that antagonize TGF-β signaling attenuates or prevents pulmonary emphysema, skeletal muscle myopathy, and myxomatous degeneration of the mitral valve. Patients with heterozygous mutations in TGF-β receptors 1 and 2 (TGFβR1 and TGFβR2) have MFS-like manifestations yet normal fibrillin-1. Paradoxically, these mutations also appear to result in increased TGF-β signaling in tissues of these patients. The resulting Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS) has much phenotypic overlap with MFS, but it also has many discriminating features (see Differential Diagnosis).

Clinical Manifestations

Skeletal System

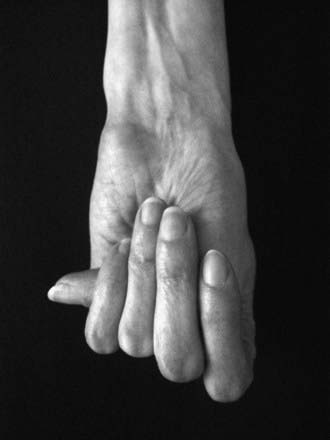

Disproportionate overgrowth of the long bones is often the most striking and immediately evident manifestation of MFS. Anterior chest deformity is caused by overgrowth of the ribs, pushing the sternum anteriorly (pectus carinatum) or posteriorly (pectus excavatum). Overgrowth of arms and legs can lead to an arm span >1.05 times the height or a reduced upper to lower segment ratio (in the absence of severe scoliosis). Arachnodactyly (overgrowth of the fingers) is generally a subjective finding. The combination of long fingers and loose joints leads to the characteristic Walker-Murdoch or wrist sign: full overlap of the distal phalanges of the thumb and fifth finger when wrapped around the contralateral wrist (Fig. 693-1). The Steinberg or thumb sign is present when the distal phalanx of the thumb fully extends beyond the ulnar border of the hand when folded across the palm (Fig. 693-2), with or without active assistance by the patient or examiner.

Thoracolumbar scoliosis is commonly present and can contribute to the systemic score of the diagnosis (Table 693-1). Protrusio acetabuli (inward bulging of the acetabulum into the pelvic cavity), which is generally asymptomatic in young adults, is best identified with radiographic imaging. Pes planus (flat feet) is commonly present and varies from mild and asymptomatic to severe deformity, wherein medial displacement of the medial malleolus results in collapse of the arch and often reactive hip and knee disturbances. Curiously, a subset of patients with the disorder present with an exaggerated arch (pes cavus). Although joint laxity or hypermobility is often identified, joints can be normal or even develop contractures. Reduced extension of the elbows is common and can contribute to the systemic score of the diagnosis (see Table 693-1). Contracture of the fingers (camptodactyly) is commonly observed, especially in children with severe and rapidly progressive MFS. Several craniofacial manifestations are often present and can contribute to the diagnosis (Fig. 693-3). These include a long narrow skull (dolicocephaly), recession of the eyeball within the socket (enophthalmos), recessed lower mandible (retrognathia) or small chin (micrognathia), malar hypoplasia (malar flattening), and downward-slanting palpebral fissures.

Table 693-1 Diagnostic Criteria for Marfan Syndrome (MFS)

In the absence of a family history of MFS, a diagnosis can be reached in 1 of 4 scenarios:

In the absence of a family history of MFS, alternative diagnoses to MFS include:

In the presence of a family history of MFS, a diagnosis can be reached in 1 of 3 scenarios:

SCORING OF SYSTEMIC FEATURES (IN POINTS)†

CRITERIA FOR CAUSAL FBN1 MUTATION

US/LS, upper segment/lower segment ratio.

* Without discriminating features of SGS, LDS, or vEDS (as defined in Table 693-2) and after TGFBR1/2, collagen biochemistry, COL3A1 testing if indicated. Other conditions/genes will emerge with time.

† Maximum total: 20 points; score ≥7 indicates systemic involvement.

From Loeys BL, Dietz HC, Braverman AC, et al: The revised Ghent nosology for the Marfan syndrome, J Med Genet 47:476–485, 2010.

Cardiovascular System

Manifestations of MFS in the cardiovascular system are conveniently divided into those affecting the heart and those affecting the vasculature. Within the heart, the atrioventricular (AV) valves are most often affected. Thickening of the AV valves is common and often associated with prolapse of the mitral and/or tricuspid valves. Variable degrees of regurgitation may be present. In children with early onset and severe MFS, insufficiency of the mitral valve can lead to congestive heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, and death in infancy; this manifestation represents the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in young children with the disorder (Chapter 422.3). Aortic valve dysfunction is generally a late occurrence, attributed to stretching of the aortic annulus by an expanding root aneurysm. Both the aortic and AV valves seem to be more prone to calcification in persons with MFS.

Ventricular dysrhythmia has been described in children with MFS (Chapter 429). In association with mitral valve dysfunction, supraventricular arrhythmia (e.g., atrial fibrillation or supraventricular tachycardia) may be seen. There is also an increased prevalence of prolonged QT interval on electrocardiographic surveys of patients with MFS. Dilated cardiomyopathy, beyond that explained by aortic or mitral valve regurgitation, seems to occur with increased prevalence in patients with MFS, perhaps implicating a role for fibrillin-1 in the cardiac ventricles. However, the incidence seems to be low, and the occurrence of mild to moderate ventricular systolic dysfunction is often attributed to mitral or aortic insufficiency or to the use of β-adrenergic receptor blockade.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree