Management of the Normal Newborn

Regina Reynolds

Elizabeth H. Thilo

Adam A. Rosenberg

The care and evaluation of the normal newborn infant includes an assessment of the mother’s past and current pregnancy history, delivery care of the newborn, and a complete physical assessment of the newborn. Elements of normal newborn care involve a risk assessment for potential medical and social problems, monitoring of feeding and elimination during a 24- to 72-hour hospital stay, performance of routine screening tests, and the transition to home with adequate outpatient follow-up. The environment should promote maternal–infant bonding and be sensitive to the needs of both mother and infant.

BOX 23.1 Commonly Performed Prenatal Screening Tests

Blood type, Rh, antibody screen

Rubella antibody screen

Hepatitis B surface antigen

Serologic test for syphilis

Human immunodeficiency virus status

Tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia

Diabetes screen

Triple- or quad-screen (maternal serum for alpha-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, estriol, inhibin A)

Group B streptococcal culture

HISTORY

The newborn infant history, no matter how brief, is always important. The history of this pregnancy, previous pregnancies, and the mother’s and father’s medical and genetic history are relevant. In the review of the current pregnancy, both antepartum and intrapartum events should be included, as well as the mother’s medical history: age, gravidity, parity, chronic medical conditions, medications, diet, tobacco use, and acute illnesses during pregnancy. The results of the prenatal screening laboratory tests (Box 23.1), ultrasound examinations, amniocentesis information, and tests of fetal well-being (nonstress tests, fetal biophysical profiles, and Doppler assessment of fetal blood flow patterns) are important. These will help to assess the risk of asphyxia, congenital and genetic abnormalities, hyperbilirubinemia, hypoglycemia, and bacterial and viral infections. The social history will identify the mother’s support system and readiness to care for a newborn infant. The family history may reveal an increased risk for genetic diseases and hyperbilirubinemia.

Preexisting diseases (e.g., asthma and diabetes mellitus) and pregnancy-specific conditions (e.g., pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia/eclampsia, preterm labor, vaginal bleeding, premature rupture of membranes, gestational diabetes, and acute infections) may alter fetal outcome. Maternal fever, fetal distress, meconium-stained fluid, type of delivery, and the infant’s condition after delivery, including the need for resuscitation, are important.

DELIVERY ROOM MANAGEMENT

The infant should be dried under a radiant heat source. The nose and mouth should be suctioned as needed. The heart rate, respirations, and color should be evaluated. A cap should be placed to avoid heat loss. Resuscitation should be initiated if indicated. Apgar scores should be assigned. A stable infant can be bundled and given to the mother. Depending on the condition, the infant can either be left with the mother or taken to the nursery for closer observation and monitoring.

GROWTH AND GESTATIONAL AGE ASSESSMENT

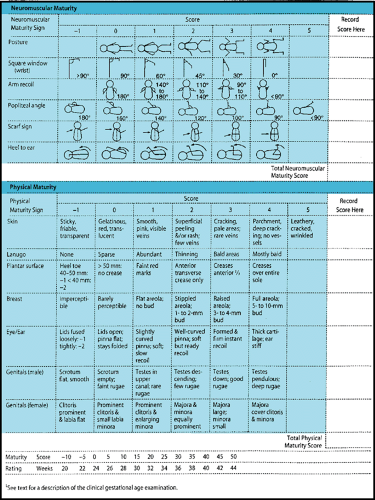

Weight, length, and occipitofrontal circumference should be measured and plotted on an appropriate growth chart to determine the infant’s growth percentiles for gestational age. Infants can be categorized as small for gestational age (SGA; less than or equal to 10% for weight), appropriate for gestational age (AGA), or large for gestational age (LGA; greater than or equal to 90% for weight). Categorization depends on the accuracy of the last menstrual period supported by an early obstetric ultrasound, if available. A postnatal examination can also be used to assess gestational age, because fetal physical characteristics and neurodevelopment progress in a predictable fashion (Fig. 23.1). Postnatal assignment of gestational age is generally within 2 weeks of the infant’s actual gestational age.

If weight, length, and head circumference are all less than or equal to 10% in an SGA infant, the infant is symmetrically growth restricted. This implies a causative factor from early pregnancy such as a constitutionally small infant or a chromosomal disorder, drug or alcohol abuse, or viral infection. Asymmetric growth restriction (only the weight less than or equal to 10%) implies a causative factor later in pregnancy, such as pregnancy-induced hypertension or placental insufficiency. Asymmetric growth restriction tends to be associated with better later growth and developmental outcome.

Infants that are SGA or LGA are at increased risk for neonatal problems. SGA infants are at increased risk for fetal distress, hypoglycemia secondary to decreased glycogen stores, and polycythemia. LGA infants are at risk for birth trauma due to shoulder dystocia, hypoglycemia secondary to hyperinsulinemia, cardiomyopathy, and polycythemia.

INITIAL NEWBORN EXAMINATION

Much of a newborn’s initial examination can be performed by inspection. For example, an infant breathing without chest wall retractions or grunting respirations with good skin color is unlikely to have underlying lung pathology. Much of the neurologic examination can also be accomplished by observation. Any previously unknown abnormalities should be pointed out to the parents at the time of discovery.

Cardiovascular

The cardiovascular examination should be performed first, ideally with the infant sleeping. Observation will show central cyanosis, the presence of which suggests congenital heart disease. Cyanosis of the hands and feet, or acrocyanosis, is normal in a newborn infant. Mild cyanosis around the mouth, or circumoral cyanosis, is normal if the tongue is pink. Next, the heart rate should be measured. A newborn heart rate can vary between 100 and 160 beats per minute while the infant is awake and quiet and may be as low as 75 to 80 beats per minute during sleep. Irregularities of rhythm are not uncommon; they usually result from premature atrial or ventricular contractions. The irregularity usually disappears when the infant becomes active and the heart rate increases. Heart murmurs in the first day of life are common and usually benign. On the other hand, congenital heart disease can be present without a murmur. Pulses should be palpated in both the upper and lower extremities. Diminished pulses in all extremities may be indicative of left ventricular dysfunction or critical aortic stenosis. Diminished femoral pulses when compared to brachial pulses suggest coarctation of the aorta or an interrupted aortic arch.

Chest and Lungs

The respiratory examination is also best accomplished when the infant is quiet. Again, observation of the chest and its movements can reveal much about the infant’s status. One should

observe for respiratory rate (normal = 30 to 60) and for chest wall retractions, grunting respiration, and nasal flaring as signs of respiratory difficulty. Tachypnea in a newborn infant is a respiratory rate greater than 60 per minute. In an infant with normal lungs, the abdomen will rise and fall with inspiration and expiration due to diaphragm excursion, but with no associated subcostal retractions. Retractions indicate accessory muscle use and increased work of breathing. Asymmetry of the chest may indicate a problem as well.

observe for respiratory rate (normal = 30 to 60) and for chest wall retractions, grunting respiration, and nasal flaring as signs of respiratory difficulty. Tachypnea in a newborn infant is a respiratory rate greater than 60 per minute. In an infant with normal lungs, the abdomen will rise and fall with inspiration and expiration due to diaphragm excursion, but with no associated subcostal retractions. Retractions indicate accessory muscle use and increased work of breathing. Asymmetry of the chest may indicate a problem as well.

Auscultation should first evaluate air entry to confirm that it is equal bilaterally. Asymmetry of air entry in conjunction with displacement of the heart tones can indicate a pneumothorax or a space-occupying mass (e.g., congenital diaphragmatic hernia). Heart tones may be distant when a pneumomediastinum is present. A decrease in air entry in combination with expiratory grunting and retractions may be indicative of respiratory distress syndrome. An irregular breathing pattern may be observed in normal newborn infants. Periods of rapid breathing interspersed with respiratory pauses for 10 to 15 seconds are referred to as periodic breathing.

Abdomen

A newborn infant’s abdomen is rounded and full. A scaphoid abdomen accompanied by respiratory distress is a sign of a diaphragmatic hernia. A mild narrow midline protrusion of the abdominal wall is likely diastasis recti, a benign condition resulting from the incomplete union of the rectus abdominus muscles. Umbilical hernias are also common. Either of the aforementioned may be revealed only with crying and may not be observed until the infant is several weeks old.

The umbilical cord should have three vessels. Superficial veins are often visible on the abdomen. Palpation of the abdomen is necessary for determination of distention; tenderness; liver, spleen, and kidney size; and masses. The liver examination is best approached by beginning palpation far below the right costal margin, palpating gently while moving upward to determine the location of the liver edge. In the normal newborn, the liver edge is generally located 1 to 2 cm below the right costal margin. The spleen is not normally palpable. Kidney palpation is more difficult. One hand should be placed under the flank and one anteriorly. Most abdominal masses in the newborn are associated with the kidney (e.g., multicystic or dysplastic, hydronephrosis). The bladder may be palpated just below the umbilicus. A palpable full bladder that does not resolve raises the concern of bladder outlet obstruction (e.g., posterior urethral valves).

Genitalia, Perineum, and Anus

Male

The inspection of the penis should reveal a foreskin that covers the entire glans penis. It does not retract, but the urethral orifice is found at the distal end and should be examined for its exact location. A hooded foreskin (a “natural circumcision”) indicates hypospadias. The examination of the scrotum should include size and degree of rugation. Palpation of the testes notes their location and size. The size of the penis and scrotum, the degree of scrotal rugation, and the location of the testes change with gestational age (Fig. 23.1).

Female

Inspection of the female external genitalia is best accomplished with the legs in frog-leg position. The labia majora usually cover the labia minora completely in a term infant. The clitoris is visible and should be examined for size. Separation of the labia brings the vaginal and urethral orifices into view. A white discharge is normal at this time and may become bloody over the first few days secondary to withdrawal of maternal estrogen. The hymen should be examined. An intact hymen without perforation should be noted. In a female infant with frank breech presentation, the labia may be edematous for several days.

Anus

The anus is inspected for location and patency. The examiner must be careful to determine patency by spreading the buttocks apart as a superficial dimple may resemble an anus.

Extremities

The infant’s extremities should be observed for obvious deformities or anomalies such as extra digits, webbing, absent extremities, and clubfeet. Palpating the extremities serves to determine the presence of fractures. All joints should be observed for active range of motion and examined for passive range of motion. Arthrogryposis, or multiple joint contractures, may indicate a paucity of amniotic fluid in utero or a congenital neuromuscular disorder, either of which limits movement in utero.

Hips

Leg length inequality or asymmetric skin folds near the buttocks may indicate a dislocated hip, but the best way to assess this is by Ortolani and Barlow maneuvers. Since the femur is generally dislocated posteriorly, the hips should be flexed to a right angle while the examiner’s finger is placed over the greater trochanter and thumb over the lesser trochanter and the hips then abducted until the knee has reached the lateral position. This allows the posteriorly dislocated femur head to relocate to the correct position. This maneuver, referred to as Ortolani sign, will result in a “clunk” into place if the hip is dislocated. Another maneuver can be used to detect a hip at risk for dislocation. With the finger and thumb in the same position, the examiner should attempt to move the femur laterally and downward with the thumb and then medially and upward. With normal hips, no movement is felt. Barlow sign, or positive movement during this maneuver indicating excessive laxity in the hip joint, means that an infant should be followed closely for later dislocation.

Back

The infant’s back should be examined by inspection for a myelomeningocele, as well as for skin pigmentation changes, tufts of hair, or dimples at the base of the spine indicating occult spinal dysraphism. The examiner should palpate the spine for occult spina bifida if a tuft of hair or dimple is present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree