Pathophysiology of sickle cell crisis in pregnancy

Clinical Features

Any woman with pregnancy, who is with refractory anaemia and who originally belongs to the Eastern India, especially with good social class, presenting with signs and symptoms of anaemia, in such cases haemoglobinopathies should be excluded.

Any pregnant woman with HbSS can present with shortness of breath, dizziness, headaches, coldness in the hands and feet and palor than normal skin or mucous membranes; jaundice with sudden pain throughout the body is a common symptom of sickle cell anaemia, and this pain is called a sickle cell crisis. Sickle cell crises often affect the bones, lungs, abdomen and joints. These crises occur when sickled red blood cells block blood flow to the limbs and organs. This can cause pain and organ damage. The pain from sickle cell anaemia can be acute or chronic, but acute pain is more common. Acute pain is sudden and can range from mild to very severe. The pain usually lasts from hours to as long as a week or more. Next common presentation of sickle cell crisis is acute chest syndrome characterised by chest pain, tachypnoea, fever, cough and arterial oxygen desaturation. Other presentations of sickle cell crisis, abnormal neurological presentation as a case of stroke or a case of acute anaemia.

Prevention and Management

Primary Prevention

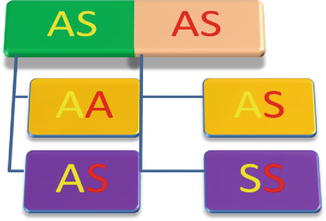

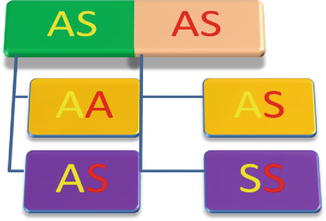

Prevention of the sickle cell anaemia or sickle cell syndrome in offsprings by avoiding marriage of sickle cell trait to another sickle cell trait or any other haemoglobinopathies, such as beta thalassaemia. The inheritance when both parents have sickle cell trait, there is a 1:4 chances with each pregnancy that the offspring will have sickle cell anaemia.

Possible Genotype of offspring of parents with sickle cell trait

Secondary Prevention

Preconception Care

SCD is associated with both maternal and fetal complications and is associated with an increased incidence of perinatal mortality, premature labour, fetal growth restriction and acute painful crises during pregnancy [3]. Some studies also describe an increase in spontaneous miscarriage, antenatal hospitalisation, pre-eclampsia, PIH, maternal mortality, delivery by caesarean section, infection, thromboembolic events and antepartum haemorrhage and infection in postpartum period [4].

Information That Is Particularly Relevant for Women Planning to Conceive Includes

The role of dehydration, cold, hypoxia, overexertion and stress in the frequency of sickle cell crises, how nausea and vomiting in pregnancy can result in dehydration and the precipitation of crises, risk of worsening anaemia, the increased risk of crises and acute chest syndrome (ACS) and the risk of increased infection (especially urinary tract infection) during pregnancy

The Assessment for Chronic Disease Complications Should Include

Screening for blood pressure and urinalysis should be performed to identify women with hypertension and/or proteinuria.

Renal and liver function tests should be performed to identify sickle nephropathy and/or deranged hepatic function.

Screening for pulmonary hypertension with echocardiography. The incidence of pulmonary hypertension is increased in patients with SCD and is associated with increased mortality. A tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity of more than 2.5 m/s is associated with a high risk of pulmonary hypertension.

Retinal screening. Proliferative retinopathy is common in patients with SCD, especially patients with HbSC, and can lead to loss of vision [5].

Screening for iron overload by serum ferritin level. In women who have been multiple transfused in the past or who have a high ferritin level, T2* cardiac magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful to assess body iron loading. Aggressive iron chelation before conception is advisable in women who are significantly iron loaded.

Screening for red cell antibodies. Red cell antibodies may indicate an increased risk of haemolytic disease of the newborn.

Women should be encouraged to have the haemoglobinopathy status of their partner.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Immunisation

Penicillin prophylaxis or the equivalent should be prescribed. Vaccination status should be determined and updated before pregnancy. Patients with SCD are hyposplenic and are at risk of infection, in particular from encapsulated bacteria such as Neisseria meningitides, Streptococcus pneumonia and Haemophilus influenzae. Daily penicillin prophylaxis is given to all patients with SCD, in line with the guidelines for all hyposplenic patients. People who are allergic to penicillin should be recommended erythromycin. In addition, women should be given H. influenza type b and the conjugated meningococcal C vaccine as a single dose if they have not received it as part of primary vaccination. The pneumococcal vaccine (Pneumovax®, Sanofi Pasteur MSD Limited, Maidenhead, UK) should be given every 5 years. Hepatitis B vaccination is recommended, and the woman’s immune status should be determined preconceptually. Women with SCD should be advised to receive the influenza and ‘swine flu’ vaccine annually [6].

Supplementation of Folic Acid

Folic acid should be given once daily both preconceptually and throughout pregnancy.

Folic acid, 5 mg, is recommended in all pregnant women to reduce the risk of neural tube defect and to compensate for the increased demand for folate during pregnancy.

Prevention of Hydroxycarbamide (Hydroxyurea)

Hydroxyurea should be stopped at least 3 months before conception. In spite of hydroxycarbamide decreases the incidence of acute painful crises and ACS, it should be stopped due to its teratogenic effects in animal.

Antenatal Care

Antenatal care should be provided by a multidisciplinary team including an obstetrician and midwife with experience of high-risk antenatal care and a haematologist.

Women with SCD should undergo medical review by the haematologist and be screened for end-organ damage (if this has not been undertaken preconceptually).

Women with SCD should aim:

Document baseline oxygen saturation, blood pressure and urinalysis at each visit and midstream urine for culture performed monthly.

Avoid precipitating factors of sickle cell crises such as exposure to extreme temperatures, dehydration and overexertion. Persistent vomiting can lead to dehydration and sickle cell crisis, and women should be advised to seek medical advice early.

The influenza vaccine should be recommended if it has not been administered in the previous year. Many women become pregnant without preconceptual care. Therefore, all of the actions in preconception care, including vaccinations, review of iron overload and red cell autoantibodies, should take place as early as possible during antenatal care.

Iron supplementation should be given only if there is laboratory evidence of iron deficiency.

Women with SCD should be considered for low-dose aspirin 75 mg once daily from 12 weeks of gestation in an effort to reduce the risk of developing pre-eclampsia.

Women with SCD should be advised to receive prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin during antenatal hospital admissions. The use of graduated compression stockings of appropriate strength is recommended in pregnancy for women considered to be at risk of venous thromboembolism,

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be prescribed only between 12 and 28 weeks of gestation owing to concerns regarding adverse effects on fetal development.

Women should be offered the routine first-trimester scan (11–14 weeks of gestation) and a detailed anomaly scan at 20 weeks of gestation. In addition, women should be offered serial fetal biometry scans (growth scans) every 4 weeks from 24 weeks of gestation.

Routine prophylactic transfusion is not recommended during pregnancy for women with SCD.

If acute exchange transfusion is required for the treatment of a sickle complication, it may be appropriate to continue the transfusion regimen for the remainder of the pregnancy. Blood should be matched for an extended phenotype including full rhesus typing (C, D and E) as well as Kell typing. Blood used for transfusion in pregnancy should be cytomegalovirus negative.

Subsequent visits at 16, 20, 24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34, 36, 38 and 40 weeks of gestation for prevention or early diagnosis and management of complications and crisis.

Offer information and advice about: timing, mode and management of the birth, analgesia and anaesthesia, induction of labour or caesarean section between 38 and 40 weeks of gestation.

Management of Sickle Cell Crisis during Pregnancy and Peripartum Period

Acute Painful Crisis

Women with SCD who become unwell should have sickle cell crisis excluded as a matter of urgency. Painful crisis is the most frequent complication of SCD during pregnancy, with between 27 and 50 % of women having a painful crisis during pregnancy, and it is the most frequent cause of hospital admission. Avoidance of precipitants such as a cold environment, excessive exercise, dehydration and stress is important. Primary care physicians should have a low threshold for referring women to secondary care; all women with pain which does not settle with simple analgesia, who are febrile, have atypical pain or chest pain or symptoms of shortness of breath should be referred to hospital.

On presentation, the woman in sickle crisis should be assessed rapidly for medical complications requiring intervention such as ACS, sepsis or dehydration. History should ascertain if this is typical sickle pain or not and if there are precipitating factors. Examination should focus on the site of pain, any atypical features of the pain and any precipitating factors, in particular whether there are any signs of infection. Pregnant women presenting with acute painful crisis should be rapidly assessed by the multidisciplinary team, and appropriate and prompt management should be started.

Investigation

Initial investigations should include full blood count, reticulocyte count and renal function. Other investigations will depend on the clinical scenario but may include blood cultures, chest X-ray, urine culture and liver function tests.

Management

Oxygen therapy: The requirement for fluids and oxygen should be assessed and fluids and oxygen administered if required. Oxygen saturations should be monitored, and facial oxygen should be prescribed if oxygen saturation falls below the woman’s baseline or below 95 % [7]. There should be early recourse to intensive care if satisfactory oxygen saturation cannot be maintained by facial or nasal prong oxygen administration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree