Chapter 280 Malaria (Plasmodium)

Epidemiology

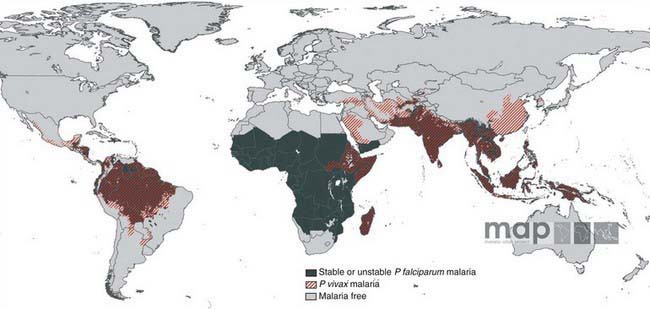

Malaria is a major worldwide problem, occurring in more than 100 countries with a combined population of over 1.6 billion people (Fig. 280-1). The principal areas of transmission are Africa, Asia, and South America. P. falciparum and P. malariae are found in most malarious areas. P. falciparum is the predominant species in Africa, Haiti, and New Guinea. P. vivax predominates in Bangladesh, Central America, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. P. vivax and P. falciparum predominate in Southeast Asia, South America, and Oceania. P. ovale is the least common species and is transmitted primarily in Africa. Transmission of malaria has been eliminated in most of North America (including the USA), Europe, and the Caribbean, as well as Australia, Chile, Israel, Japan, Korea, Lebanon, and Taiwan.

Pathogenesis

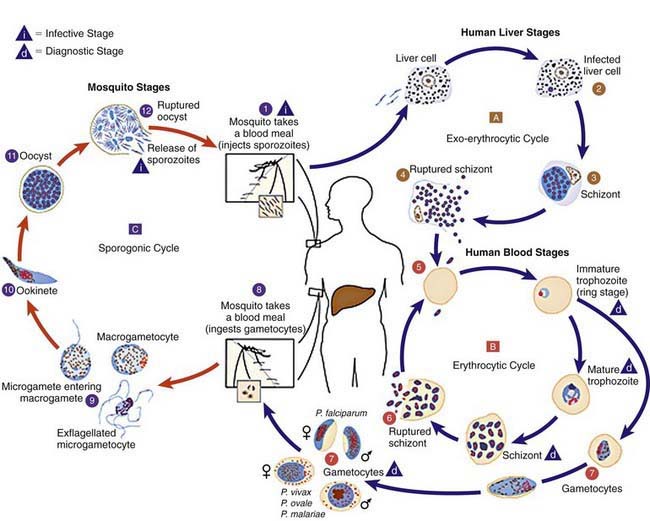

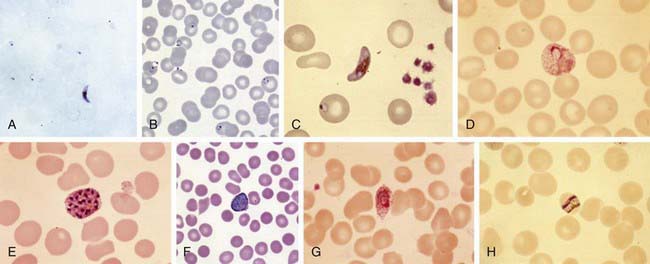

Plasmodium species exist in a variety of forms and have a complex life cycle that enables them to survive in different cellular environments in the human host (asexual phase) and the mosquito (sexual phase) (Fig. 280-2). A marked amplification of Plasmodium, from approximately 102 to as many as 1014 organisms, occurs during a 2-step process in humans, with the 1st phase in hepatic cells (exoerythrocytic phase) and the 2nd phase in the red cells (erythrocytic phase). The exoerythrocytic phase begins with inoculation of sporozoites into the bloodstream by a female Anopheles mosquito. Within minutes, the sporozoites enter the hepatocytes of the liver, where they develop and multiply asexually as a schizont. After 1-2 wk, the hepatocytes rupture and release thousands of merozoites into the circulation. The tissue schizonts of P. falciparum, P. malariae, and apparently P. knowlesi rupture once and do not persist in the liver. There are 2 types of tissue schizonts for P. ovale and P. vivax. The primary type ruptures in 6-9 days, and the secondary type remains dormant in the liver cell for weeks, months, or as long as 5 yr before releasing merozoites and causing relapse of infection. The erythrocytic phase of Plasmodium asexual development begins when the merozoites from the liver penetrate erythrocytes. Once inside the erythrocyte, the parasite transforms into the ring form, which then enlarges to become a trophozoite. These latter 2 forms can be identified with Giemsa stain on blood smear, the primary means of confirming the diagnosis of malaria (Fig. 280-3). The trophozoite multiplies asexually to produce a number of small erythrocytic merozoites that are released into the bloodstream when the erythrocyte membrane ruptures, which is associated with fever. Over time, some of the merozoites develop into male and female gametocytes that complete the Plasmodium life cycle when they are ingested during a blood meal by the female anopheline mosquito. The male and female gametocytes fuse to form a zygote in the stomach cavity of the mosquito. After a series of further transformations, sporozoites enter the salivary gland of the mosquito and are inoculated into a new host with the next blood meal.

Figure 280-2 Life cycle of Plasmodium spp.

(From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Laboratory diagnosis of malaria: Plasmodium spp. [pdf]. www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/PDF_Files/Parasitemia_and_LifeCycle.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2010.)

(A, B, and F from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: DPDx: laboratory identification of parasites of public health concern. www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/. C, D, E, G, and H courtesy of David Wyler, Newton Centre, MA.)

Clinical Manifestations

P. falciparum is the most severe form of malaria and is associated with higher density parasitemia and a number of complications. The most common serious complication is severe anemia, which also is associated with other malaria species. Serious complications that appear unique to P. falciparum include cerebral malaria, acute renal failure, respiratory distress from metabolic acidosis, algid malaria and bleeding diatheses (see later section on complications, and Table 280-1). The diagnosis of P. falciparum malaria in a nonimmune individual constitutes a medical emergency. Severe complications and death can occur if appropriate therapy is not instituted promptly. In contrast to malaria caused by P. ovale, P. vivax, and P. malariae, which usually results in parasitemias of less than 2%, malaria caused by P. falciparum can be associated with parasitemia levels as high as 60%. The differences in parasitemia reflect the fact that P. falciparum infects both immature and mature erythrocytes, while P. ovale and P. vivax primarily infect immature erythrocytes and P. malariae infects only mature erythrocytes. Like P. falciparum, P. knowlesi has a 24 hr replication cycle and can also lead to very high density parasitemia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree