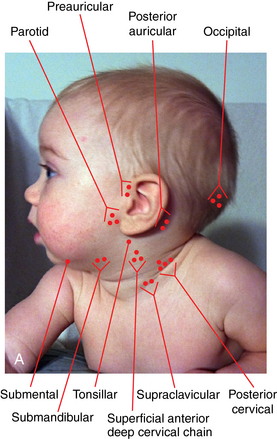

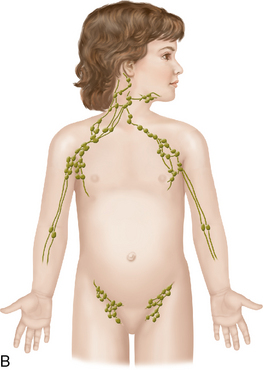

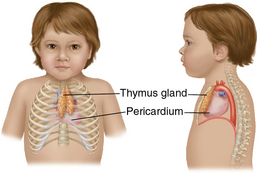

CHAPTER 10 The lymphatic system is established in the mesoderm layer during the third week of embryonic development, and the development of the primary lymphoid organs, the thymus and bone marrow, begin during the fifth to sixth week of fetal development.1 The secondary lymphoid organs—the spleen, lymph nodes, and lymphoid tissue—develop soon after the primary organs and are well developed at birth. The ectoderm gives rise to the epithelial linings of the glandular cells of the large organs that make up the lymphatic system.1 The spleen, lymph nodes, and lymphoid tissue are small at birth and mature rapidly after exposure to antigens or microbes during the postnatal period. The thymus is the largest lymphoid tissue in the body at birth and continues to develop during the first year of life as the immune system develops. At puberty, the thymus begins slowly regressing as the immune system is well established in the lymphoid tissue.1 The lymphatic system forms an extensive network throughout the body and is composed of capillaries, collecting vessels, lymph nodes, and lymphoid organs. The bone marrow and thymus, which are the central lymphoid organs, provide the center for the production and maturation of the immune cells.1 The peripheral lymphoid organs—the spleen, tonsils, appendix, and lymphatic tissue in the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and reproductive systems—concentrate antigens or immunogens and promote the cellular interactions of the immune response throughout the body to seek out and destroy microbes.1 Lymph nodes are small aggregates of lymphoid tissue lying along lymphatic vessels throughout the body and consist of outer cortical layers and an inner medullary layer. The terms lymph gland and lymph node are often used interchangeably, and both terms can be applied to the lymphatic system. A gland is an organ that produces a substance or secretion, and a node is a swelling or protuberance. The lymph nodes throughout the body are filters for the collection vessels. Each lymph node processes lymph from the surrounding anatomical area. Lymph nodes remove antigens and microbes from the lymph before it enters the bloodstream, serve as the site of the body’s immune response, and aid in the maturation of lymphocytes and monocytes. The T lymphocytes are responsible for cell-mediated immunity and aid in antibody production. They are activated in the cortex of the lymph nodes and proliferate to fight antigens. The B lymphocytes are essential for humoral immunity. They interact with the T lymphocytes and migrate to the medulla to mature before releasing antibodies. Many interactions in the immune system depend upon the secretion of chemical mediators such as cytokines and chemokines. Cytokines are soluble proteins secreted by cells of the immune system and mediate many functions within the cell. Chemokines are cytokines that stimulate the immune system and activate inflammatory cells.1 They are implicated in acute and chronic conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, and rheumatoid arthritis. Figure 10-1 illustrates the lymph glands in the head and neck area and gives a view of the lymphatic chain in the body. The thymus gland is embedded beneath the upper sternum above the heart and is a fully developed organ in the term infant. The thymus gland is prominent in the mediastinum of the newborn and infant in the first year of life, often shadowing the cardiac silhouette on radiographs (Figure 10-2). In the infant, the thymus begins to produce mature T lymphocytes and plays an important role in cell-mediated immunity. In puberty, when the immune system is well established, the thymus decreases in size and is gradually and almost entirely replaced by adipose tissue. Some thymus tissue persists, but is usually undetectable in the adult. The variable size of the lymphoid tissue in early and middle childhood may be one of the contributing factors of pediatric disordered breathing, but other common causes include congenital craniofacial abnormalities, chronic nasal allergy, recurrent respiratory infections, and childhood obesity. All children and adolescents should now be screened for snoring.2 It is important to differentiate primary snoring from snoring associated with disordered breathing. Pediatric sleep-disordered breathing is characterized by prolonged partial upper airway obstruction and intermittent obstructive apnea that disrupts normal sleep patterns.2 The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea is currently 1% to 3% in the pediatric population, and the prevalence of primary snoring is estimated to be 3% to 12%.3

Lymphatic system

Embryological development

Development variations

Anatomy and physiology

Lymphatic system

Physiological variations

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree