Background

Among adolescent pregnancies, 75% are unintended. Greater use of highly-effective contraception can reduce unintended pregnancy. Although multiple studies discuss adolescent contraceptive use, there is no consensus regarding the use of long-acting reversible contraception as a first-line contraception option.

Objective

We performed a systematic review of the medical literature to assess the continuation of long-acting reversible contraceptives among adolescents.

Study Design

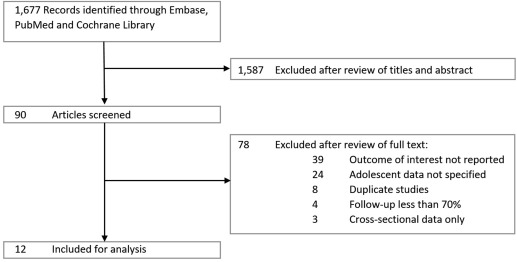

Ovid-MEDLINE, Cochrane databases, and Embase databases were searched using key words relevant to the provision of long-acting contraception to adolescents. Articles published from January 2002 through August 2016 were selected for inclusion based on specific key word searches and detailed review of bibliographies. For inclusion, articles must have provided data on method continuation, effectiveness, or satisfaction of at least 1 long-acting reversible contraceptive method in participants <25 years of age. Duration of follow-up had to be ≥6 months. Long-acting reversible contraceptive methods included intrauterine devices and the etonogestrel implant. Only studies in the English language were included. Guidelines, systematic reviews, and clinical reviews were examined for additional citations and relevant points for discussion. Of 1677 articles initially identified, 90 were selected for full review. Of these, 12 articles met criteria for inclusion. All studies selected for full review were extracted by multiple reviewers; inclusion was determined by consensus among authors. For studies with similar outcomes, forest plots of combined effect estimates were created using the random effects model. The meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology guidelines were followed. Primary outcomes measured were continuation of method at 12 months, and expulsion rates for intrauterine devices.

Results

This review included 12 studies, including 6 retrospective cohort studies, 5 prospective observational studies, and 1 randomized controlled trial. The 12 studies included 4886 women age <25 years: 4131 intrauterine device users and 755 implant users. The 12-month continuation of any long-acting reversible contraceptive device was 84.0% (95% confidence interval, 79.0–89.0%). Intrauterine device continuation was 74.0% (95% confidence interval, 61.0–87.0%) and implant continuation was 84% (95% confidence interval, 77.0–91.0%). Among postpartum adolescents, the 12-month long-acting reversible contraceptive continuation rate was 84.0% (95% confidence interval, 71.0–97.0%). The pooled intrauterine device expulsion rate was 8.0% (95% confidence interval, 4.0–11.0%).

Conclusion

Adolescents and young women have high 12-month continuation of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Intrauterine devices and implants should be offered to all adolescents as first-line contraceptive options.

Introduction

Almost 1 in 5 female adolescents and young women will give birth before age 20 years. Of the approximately 574,000 adolescent pregnancies that occur each year in the United States, 75% are unintended. Although the United States has experienced a recent decline in teen pregnancy, the rate remains higher than the rates in many other comparable developed nations. Rates of unintended pregnancy in young women in poverty have increased while rates in more affluent women have declined. Racial and ethnic disparities also exist. The pregnancy rates among black and Latina teens are over twice that of white teens. Adolescents who become pregnant, and especially those pregnant again within 1 year of the previous pregnancy, are more likely to subsequently experience serious negative educational, economic, health, and social events than are adolescent females of the same age, race, and ethnicity who did not become pregnant. Inconsistent use of contraceptives, use of less-effective methods, and nonuse of contraceptives contribute to the high rate of unintended pregnancy among US adolescents.

Greater use of highly effective contraception can reduce unintended pregnancy rates in this at-risk population. Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods include intrauterine devices (IUDs) and the etonogestrel (ENG) subdermal implant. There are 2 general groups of IUDs commercially available in the United States: hormonal and nonhormonal. The primary mechanism of the levonorgestrel-containing IUD (LNG-IUD) is the release of the progestin levonorgestrel, which thickens cervical mucus, thereby preventing fertilization. The primary mechanism of the nonhormonal copper-containing IUD (Cu-IUD) is the release of copper ions that inhibit sperm function, preventing fertilization. The reversible method of contraception most commonly used by US women is the oral contraceptive pill. The failure rate of combined hormonal contraceptive methods (oral contraceptive pill, ring, or patch) is >20-fold higher than that of LARC methods. The safety of LARC methods is well-established and has led to their endorsement as first-line contraceptive methods by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). In the Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) acknowledge that LARCs are the most effective reversible methods and are appropriate for adolescents and nulliparous women. Although multiple studies discuss continuation of LARC methods in the adolescent population, there is no consensus of continuation rates for IUDs and implants among adolescents and young women. The objective of this systematic review is to provide an assessment of the findings of the medical literature of the use of LARC methods in young women age <25 years. Our hypothesis was that continuation rates for adolescents using the IUD or implant are high (>75%) at 1 year from initiation.

Materials and Methods

Search strategies and data sources

We included both randomized controlled trials (RCT) and observational trials in our review. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines were followed. A literature search was performed of the Ovid-MEDLINE, Cochrane databases, and Embase databases using key words relevant to the provision of long-acting contraception to adolescents. Because the goal was to look at contemporary LARC methods, the search was limited to articles published in 2002 or later. The search was limited to English-language articles. The full search terms and strategy are shown in online supplementary material .

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in our final analysis, articles must have reported data on continuation of at least 1 LARC method among participants with at least 6 months of follow-up. While the primary outcome was continuation at 12 months, studies were included that have 6-month continuation as a secondary outcome when assessing expulsion. Included studies must have provided actual continuation of participants, not estimated continuation. “Adolescent” is not consistently defined by specific ages in the medical literature, therefore we included women ≤24 years of age. When a study included age groups extending >24 years of age, the published article must have stratified the results by age group and must have included at least 1 cohort of at least 20 participants exclusively ≤24 years of age. When data were not reported for such a cohort, the study was excluded. In addition, studies with >30% loss to 12-month follow-up were excluded. Studies were also excluded if they described LARC among special populations of adolescents (eg, those with chronic disease such as HIV). Studies examining postabortion and postpartum adolescents were included. Two investigators (J.T.D. and D.A.K.) independently assessed titles and abstracts for inclusion. Articles that both of them deemed to meet inclusion criteria were included. In cases of disagreement, the senior author (J.F.P.) determined whether inclusion criteria were met.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by 2 investigators (J.T.D. and D.A.K.) for all included studies. Data extracted included the study methodology, number of participants, age range, type of LARC used, and insertion setting (postpartum, postabortion, or interval). Interval insertion was defined as not during the initial postpartum period. Additional data extracted were the time of follow-up, primary and secondary outcomes measured, and attrition. We noted the number (and ages) of adolescents included, and their specific subgroup outcomes. We also recorded the number of reported IUD expulsions.

Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed using the checklist described by Downs and Black. Studies received points for their low risks of bias in several categories: reporting, external validity, bias, and confounding. There were a total of 27 points assigned in the following categories: reporting (10 points possible), external validity (3 points possible), bias (7 points possible), and confounding (7 points possible). Studies were grouped according to their score, with high scores indicating lower risk bias: excellent (25-27), good (19-24), fair (14-18), and poor (<14).

Data synthesis

The proportion of women continuing LARC methods were pooled for continuation rates of 6 and 12 months using a random effects model. Individual estimates were weighted by their SE. The same technique was used for proportions of women with expulsion of their IUDs. Heterogeneity of studies was assessed by using I 2 and further characterized using Egger test of publication bias.

Materials and Methods

Search strategies and data sources

We included both randomized controlled trials (RCT) and observational trials in our review. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines were followed. A literature search was performed of the Ovid-MEDLINE, Cochrane databases, and Embase databases using key words relevant to the provision of long-acting contraception to adolescents. Because the goal was to look at contemporary LARC methods, the search was limited to articles published in 2002 or later. The search was limited to English-language articles. The full search terms and strategy are shown in online supplementary material .

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in our final analysis, articles must have reported data on continuation of at least 1 LARC method among participants with at least 6 months of follow-up. While the primary outcome was continuation at 12 months, studies were included that have 6-month continuation as a secondary outcome when assessing expulsion. Included studies must have provided actual continuation of participants, not estimated continuation. “Adolescent” is not consistently defined by specific ages in the medical literature, therefore we included women ≤24 years of age. When a study included age groups extending >24 years of age, the published article must have stratified the results by age group and must have included at least 1 cohort of at least 20 participants exclusively ≤24 years of age. When data were not reported for such a cohort, the study was excluded. In addition, studies with >30% loss to 12-month follow-up were excluded. Studies were also excluded if they described LARC among special populations of adolescents (eg, those with chronic disease such as HIV). Studies examining postabortion and postpartum adolescents were included. Two investigators (J.T.D. and D.A.K.) independently assessed titles and abstracts for inclusion. Articles that both of them deemed to meet inclusion criteria were included. In cases of disagreement, the senior author (J.F.P.) determined whether inclusion criteria were met.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by 2 investigators (J.T.D. and D.A.K.) for all included studies. Data extracted included the study methodology, number of participants, age range, type of LARC used, and insertion setting (postpartum, postabortion, or interval). Interval insertion was defined as not during the initial postpartum period. Additional data extracted were the time of follow-up, primary and secondary outcomes measured, and attrition. We noted the number (and ages) of adolescents included, and their specific subgroup outcomes. We also recorded the number of reported IUD expulsions.

Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed using the checklist described by Downs and Black. Studies received points for their low risks of bias in several categories: reporting, external validity, bias, and confounding. There were a total of 27 points assigned in the following categories: reporting (10 points possible), external validity (3 points possible), bias (7 points possible), and confounding (7 points possible). Studies were grouped according to their score, with high scores indicating lower risk bias: excellent (25-27), good (19-24), fair (14-18), and poor (<14).

Data synthesis

The proportion of women continuing LARC methods were pooled for continuation rates of 6 and 12 months using a random effects model. Individual estimates were weighted by their SE. The same technique was used for proportions of women with expulsion of their IUDs. Heterogeneity of studies was assessed by using I 2 and further characterized using Egger test of publication bias.

Results

Study selection

Using our search strategy, 1677 citations were identified. From these titles and abstracts, 90 articles appeared to meet our inclusion criteria. Of these, 39 were excluded because they did not provide data on the primary endpoint; 24 were excluded because the primary endpoint was not stated for the adolescent subgroup; 8 studies were separate analyses of other included studies; 4 were excluded because follow-up was <70%; and an additional 3 studies were excluded because they were cross-sectional studies. After exclusions, 12 articles that met all criteria and were included for analysis. Figure 1 shows the selection of included articles.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of individual studies are presented in Table 1 . A total of 4886 adolescent and young adult women (<25 years of age) were included from all studies. Sample sizes from the included studies ranged from 23-1146. Among the included studies, 755 subjects used the subdermal implant and 4131 used the IUD. There were 8 studies that included the Cu-IUD, 9 studies that included the LNG-IUD, and 4 studies that included the ENG implant. Many of the studies compared LARC methods. Comparisons between Cu-IUD and LNG-IUD were performed in 8 studies ; 2 studies included cohorts of both IUD and the ENG implant users. Three studies included only data for 6 months of continuation, which account for a total of 1242 patients. LARCs were placed postpartum in 4 studies, and interval placement in 3 studies. There were 2 studies that did not specify the timing of LARC placement. One study allowed placement postpartum, postabortion, or interval.

| Author | Year | Study type | Age range, y | n | LARC | Follow-up, mo | Outcome | Insertion timing | Country | Nulliparous | Attrition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Godfrey et al | 2010 | RCT | 14–18 | 23 | Cu-IUD LNG-IUD | 6 | 6 mo Continuation Expulsion | Interval | US | 52% | 2% |

| Guazzelli et al | 2010 | Prospective cohort | <20 | 44 | Implant | 12 | 12 mo Continuation | Postpartum | Brazil | 0 | 6% |

| Alton et al | 2012 | Retrospective cohort | 11–21 | 233 | Cu-IUD LNG-IUD | 96 | 12 mo Continuation | Interval | US | 30% | NR |

| Rosenstock et al | 2012 | Prospective cohort | 14–19 | 763 | Cu-IUD LNG-IUD Implant | 12 | 12 mo Continuation | Interval, postpartum, postabortion | US | 77% | 6% |

| Teal and Sheeder | 2012 | Retrospective cohort | 14–23 | 136 | Cu-IUD LNG-IUD | 12 | 12 mo Continuation Expulsion | Postpartum | US | 0 | 14% |

| Tocce et al | 2012 | Prospective cohort | 13–23 | 171 | Implant | 12 | 12 mo Continuation 6 mo Continuation | Postpartum | US | 0 | 5% |

| Garbers et al | 2013 | Retrospective cohort | 14–19 | 73 | Cu-IUD | 6 | 6 mo Continuation | NR | US | NR | 15% |

| Aoun et al | 2014 | Retrospective cohort | 13–24 | 999 | Cu-IUD LNG-IUD | 36 | 12 mo Continuation Expulsion | NR | US | 16% | 13% |

| Cohen et al | 2016 | Prospective cohort | 13–22 | 244 | Cu-IUD LNG-IUD Implant | 12 | 12 mo Continuation 6 mo Continuation Expulsion | Postpartum | US | 0 | 17% |

| Teal et al | 2015 | Retrospective cohort | 13–24 | 1146 | Cu-IUD LNG-IUD | 6 | 6 mo Continuation Expulsion | Interval | US | 59% | 30% |

| Berlan et al | 2016 | Retrospective cohort | 12–22 | 750 | Implant | 12 | 12 mo Continuation | Interval | US | 85% | NR |

| Gemzell-Danielsson et al | 2016 | Prospective cohort | 12–17 | 304 | LNG-IUD | 12 | 12 mo Continuation AE | Interval | Multi | 98% | 1% |

| Total N: | 4886 |

Of the 12 studies, 1 study was a RCT, and the remaining 11 were observational studies. Five studies were prospective cohort studies and 6 studies were retrospective cohort studies. Overall, approximately 34% of adolescents in the included studies were nulliparous. Follow-up ranged between 6-96 months, with median follow-up of 12 months. Median follow-up was the same for both prospective and retrospective studies. Ten of the included studies were performed in the United States, 1 study was performed in Brazil, and 1 study was a multinational study.

Randomized controlled trial

Godfrey and colleagues performed a pilot RCT that randomized 23 adolescents and young women between age 13-18 years to either Cu-IUD (n = 11) or LNG-IUD (n = 12). Subjects had an interval IUD placement or placement at least 7 weeks postpartum. Continuation at 6 months was 75% for LNG-IUD and 45% for Cu-IUD ( P = .15). Despite high discontinuation, the majority of subjects reported being satisfied with their IUD at 6 months (70% of LNG-IUD and 80% of Cu-IUD users). Two Cu-IUD expulsions, but no LNG-IUD expulsions, were reported.

Observational studies

In 2012, Rosenstock and colleagues published a subanalysis of the adolescents participating in the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. CHOICE was a prospective observational study of women in the St Louis, MO, area who were provided with no-cost contraception for 2-3 years. All participants received tier-based contraceptive counseling and their method of choice. Of the 763 adolescents and young women (14-19 years) who started a LARC method at baseline, continuation at 12 months was 81% among LNG-IUD users, 76% among Cu-IUD users, and 82% among implant users. By 12 months, <6% of adolescent participants had been lost to follow-up. Expulsion of IUDs was not reported in the article. However, another article from the same study population estimated the risk of expulsion at 10.5 per 100 IUD users per 12 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.0–13.5) among women <20 years of age.

Guazzelli and colleagues included 44 adolescents who presented <6 months postpartum for LARC at a clinic in São Paolo, Brazil. The cohort had an average age of 17 years; 91% had 1 child and the remainder had ≥2. All women included had a subdermal implant placed and were followed prospectively for 1 year; 6% were lost to follow-up. Continuation was 94% at 12 months, and the rate of amenorrhea was 38% by 12 months. Another prospective study was performed by Cohen and colleagues. Adolescents and young women (ages 13-22 years) who chose postplacental IUDs (n = 82) or subdermal implant (n = 162) to be placed prior to discharge were included. At 12 months, IUD continuation was 62% and implant continuation was 72%. The observed IUD expulsion rate reported was 21%.

Tocce and colleagues performed a prospective cohort study of 171 postpartum adolescents and young women (ages 13-24 years) who had subdermal implant placed prior to discharge. This group was compared to a control group of adolescents who chose any other method. The primary outcomes were contraceptive continuation and repeat pregnancy rates. Continuation of the implant was 97% at 6 months and 86% at 12 months. The odds of pregnancy were 8 times higher for those who did not choose immediate postpartum implant (odds ratio, 8.0; 95% CI, 2.8–23.0) compared to women who did choose insertion.

In a subgroup analysis of a large multinational prospective phase III trial, Gemzell-Danielsson and colleagues evaluated the use of a new IUD among girls and adolescents (12-17 years of age). The IUD evaluated was a LNG-IUD containing 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel released at a rate of 8 μg/d. There were 304 adolescents who had the LNG-IUD inserted, and all were followed up for 12 months. Continuation at 12 months was 83%. There were 10 expulsions (3%) during 12 months.

In a retrospective cohort study, Alton and colleagues identified 233 adolescents age <21 years who had each received a Cu-IUD (n = 11) or LNG-IUD (n = 222) during an 8-year period. The IUDs had been placed at a private faculty clinic or at a hospital-based Title X clinic. Of their study population, 70% were parous and the median age at insertion was 16 years. At 12 months, continuation was 70% among the youngest group of adolescents (age <18 years) and 89% among those age 18-21 years. The number of IUD expulsions was not reported.

Teal and Sheeder performed a retrospective cohort study of parous adolescents and young women (14-23 years of age) who had each received a LNG-IUD or Cu-IUD. The average insertion time was 8 months postpartum (none were placed immediately after placental delivery). Median continuation of IUD use was 14 months; range was not reported. There was no difference in continuation based on type of IUD. Continuation rates were censored at 60 months. Twelve-month continuation was 55%, and an expulsion rate of 15% was observed.

Garbers and colleagues retrospectively reviewed charts of 73 adolescents and young women (ages 14-19 years) who had sought family planning services and had Cu-IUDs placed. According to chart review, 6-month continuation of the Cu-IUD was 88%. IUD expulsions were not reported.

Aoun and colleagues reviewed charts of 999 adolescents and young women (age 14-24 years) who received a Cu-IUD or LNG-IUD. At the time of insertion, approximately 16% of participants were nulliparous. At 12 months, continuation was 80%. Only 13% were lost to follow-up. An expulsion rate of 4% was observed.

Teal and colleagues performed a retrospective study of adolescents and young women (13-24 years) who desired an IUD. The goal of this study was to quantify complications and unsuccessful insertions among 1177 who had an attempted IUD placement. Among the 1146 who had a successful insertion, continuation of the IUD was 95% at 6 months. A 2% IUD expulsion rate was observed.

A retrospective study was performed by Berlan and colleagues evaluating 12-month continuation of the subdermal implant by adolescents 12-22 years of age. The majority (85%) were nulliparous. Of 750 patients who had the device placed, only 10% had discontinued by 12 months (90% continuation).

Assessment of risk of bias

The majority of the included studies were of fair or good quality under the Downs and Black methodology. Overall, the average score for reporting results was 9 of 10 points; average scores for external validity were 2.25 of 3 points; average scores for bias were 4 of 7 points; and the average score for confounding was 2.4 of 7 points. See Table 2 for results. The majority of studies had low scores for confounding and bias, which mainly is due to study design. Because only 1 study included was a RCT, there is a higher risk of bias among the remaining studies. However, 1 advantage of a meta-analysis of observational studies is generalizability and obtaining estimates that are closer to real-life continuation. In practice, women are able to choose their contraceptive method and are not randomly assigned one.