Chapter 46

Liver Disease

David B. Wax MD, Yaakov Beilin MD, Michael Frölich MD, MS

Chapter Outline

Liver Diseases

Liver diseases can be either incidental or unique to pregnancy and complicate as many as 3% of all pregnancies. The more common conditions are addressed in this chapter, and the hepatic aspects of preeclampsia/eclampsia and HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome are discussed in Chapter 36.

Liver Diseases Incidental to Pregnancy

Viral Hepatitis

The presentation of viral hepatitides ranges from mild, nonclinical illness to fulminant hepatic necrosis. Viral hepatitis is the most common cause of jaundice and most frequent reason for gastroenterology consultation during pregnancy.1 Six types—hepatitis A, B, C, D, E, and G—have been identified and are associated with specific viruses. Types A, B, and C are the most common. Infrequently, hepatitis can also be caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV), yellow fever virus, rubella virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), or cytomegalovirus (CMV).

Hepatitis A (HAV) and hepatitis E (HEV) are viral infections of hepatocytes that typically spread by oral ingestion of food or water contaminated with feces from infected individuals. Although endemic in other countries, the current all-time low incidence of 1.3 per 100,000 in the United States is attributed to good sanitation.2 The incidence of HAV infection has been reduced by vaccination for preexposure prophylaxis; immune globulin is available for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent or attenuate infection. Clinically, a preicteric phase typically occurs with nonspecific viral symptoms, followed by an icteric phase with jaundice and acholic stools. Acute treatment is supportive. Chronic HAV infection does not occur, but a prolonged or relapsing course occurs in up to 20% of patients and an acute fulminant course occurs in less than 1% of patients.3 Vertical transmission to the fetus has been reported rarely.4

HEV infection may be largely asymptomatic. In symptomatic patients, the disease is usually self-limited. Pregnant women and patients already infected with another hepatitis virus, however, are more likely to develop fulminant hepatic failure. Chronic HEV infection may occur in immunosuppressed patients, and vertical transmission can occur.5 Pegylated interferon and/or ribavirin treatment for chronic HEV infection has shown moderate success, and HEV vaccines are under development.6

Hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis D (HDV) are usually transmitted via percutaneous or permucosal exposure to infected body fluids. In high-prevalence areas, HBV infection is most commonly acquired perinatally or in early childhood. In low-prevalence areas, infection is primarily acquired in adulthood through sexual contact or intravenous drug abuse. The incidence is decreasing after widespread vaccination and safety precautions in health care settings. Postexposure prophylaxis with HBV vaccination alone or a combination of vaccination with HBV immunoglobulin is highly effective in preventing HBV transmission in adults as well as in infants of HBV-infected mothers and may prevent perinatal transmission in 90% of cases. The majority of acute infections are asymptomatic, with only 30% of adults developing typical symptoms of hepatitis, and less than 0.5% developing fulminant hepatitis. Most cases can be managed with supportive treatment, although nucleoside analogue therapy may improve prognosis in severe cases. Chronic HBV develops in less than 5% of adults but in more than 20% of children, and exacerbations of chronic HBV may occur in the postpartum period. The 5-year cumulative incidence of cirrhosis in those with chronic HBV may be as high as 20%, and once cirrhosis has developed the annual risk for hepatocellular carcinoma may be as high as 5%. Treatment of chronic HBV, therefore, is aimed at clearance of virus to prevent the development of cirrhosis and cancer. Vertical transmission to the fetus from hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg)-positive mothers can be as high as 90% without attempts to prevent transmission.7 Nucleoside analogue antiviral therapy with lamivudine has a favorable side-effect and safety profile and may be used during pregnancy to reduce vertical transmission, but there is significant risk for viral resistance.8 In contrast, interferon therapy has a finite course of treatment and an increased chance of viral clearance and significantly reduces the risk for cirrhosis and liver cancer; however, it has more side effects and is contraindicated during pregnancy.9 Current recommendations are to administer HBV vaccination to all neonates, and to administer hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) to all offspring of infected mothers.10

HDV is dependent on HBV co-infection to replicate. Acute co-infection with both viruses can be more severe than acute HBV infection alone and may result in acute liver failure. HDV superinfection in the setting of chronic HBV results in chronic HDV infection in most patients, and these patients have more rapid progression to cirrhosis.11

Hepatitis C (HCV) transmission most commonly occurs from transfusion of infected blood products or injection of contaminated drugs (both illicit and iatrogenic). Maternal-fetal and sexual transmission are less common routes of transmission. Initial infection is generally asymptomatic, but up to 30% of patients develop acute hepatitis. In patients with acute HCV infection that has not cleared spontaneously within 12 weeks, treatment with pegylated interferon may be used to prevent chronic infection, with treatment success in up to 98% of patients. In most asymptomatic and untreated cases, infection persists for over 6 months and leads to chronic infection with progression to cirrhosis in up to 30% of patients within 30 years. Thus, HCV is the leading cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer (which develops in up to 3% of patients per year) and a primary indication for liver transplantation in the developed world. Depending on the severity of liver fibrosis, therapy may be warranted to prevent these complications. Combination treatment with pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and a protease inhibitor can result in a sustained virologic response in up to 80% of patients, but is contraindicated during pregnancy.12,13

Hepatitis G (HGV) is transmitted parenterally, sexually, or vertically. In the United States, nearly 20% of all blood preparations are infected with HGV. Although there have been reports of acute, fulminant, and chronic hepatitis and hepatic fibrosis, HGV replicates predominantly in the hematopoietic system rather than in hepatocytes. Clinical significance is mostly for those co-infected with HCV or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or for individuals with hematologic cancers.14

Cholecystitis

Pregnancy may promote gallstone formation. Cholelithiasis is present in up to 3% of pregnant women, although acute cholecystitis occurs in only 0.1% of pregnancies.15 Patients may have right upper quadrant pain, fever, and leukocytosis, and diagnosis is generally made by ultrasonography. Serious complications include cholangitis, pancreatitis, gangrenous cholecystitis, and perforation. To avoid surgery, conservative treatment may be considered in mild cases and includes intravenous hydration, antibiotics, opioid analgesia, bowel rest, and possibly percutaneous cholecystostomy. There is some evidence, however, that there is greater risk for fetal demise among patients treated conservatively.16 When surgical intervention is required, both laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy have been safely used during pregnancy.15

Liver Abscess

Liver abscess can develop from infection by a range of organisms with various sites of entry. Organisms with a predilection for the liver include parasites such as Entamoeba, Echinococcus, Clonorchis, and Ascaris. Direct inoculation during medical instrumentation or hematogenous spread from intravenous drug abuse or endocarditis can occur. Appendicitis, diverticulitis, or other intra-abdominal infections may spread to the liver. Fungal infections are also possible in immunocompromised patients. Management of liver abscess includes antimicrobial agents, percutaneous or open drainage, and possibly surgical resection.17 The condition is rare during pregnancy, but treatment modalities are similar to those described for the nonpregnant woman.18

Autoimmune Diseases

Autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis are conditions that may overlap and may also be associated with other extrahepatic autoimmune disorders.19,20 All may lead to end-stage liver disease, and treatment with corticosteroids, other immunosuppressants, and/or ursodeoxycholic acid is aimed at preventing this progression. For advanced and intractable disease, liver transplantation may be necessary. Pregnancy is associated with a 33% incidence of disease flares (mostly in the postpartum period), and an 11% incidence of serious maternal adverse events associated with hepatic decompensation, as well as increased neonatal intensive care requirement. Immunosuppressive therapy during pregnancy is reportedly safe and effective in reducing disease flares.

Vascular Syndromes

Budd-Chiari syndrome involves thrombosis of the hepatic vein or suprahepatic inferior vena cava and may be associated with pregnancy or other hypercoagulable states.21 Hepatic venous congestion can also result from right-sided heart failure or other cardiopulmonary diseases that increase central venous pressure or from mechanical compression or compartment syndrome that impedes hepatic venous outflow. This congestive hepatopathy can ultimately lead to fibrosis, portal hypertension, and liver failure. Portal vein thrombosis may also occur and cause portal hypertension without cirrhosis. Initial therapy is anticoagulation, and liver transplantation may ultimately be required in chronic cases. Disruption of hepatic arterial and/or portal venous inflow can result in acute ischemic/hypoxic hepatitis, especially in the setting of other coexisting liver disease. This “shock liver” syndrome can occur in the setting of perioperative hypotension, critical illness with septic shock or cardiac arrest, pulmonary embolus, heart failure, or heatstroke.22,23

Metabolic Diseases

Wilson’s disease is a condition of reduced copper excretion. Gradual copper accumulation in the liver can lead to cirrhosis, while rapid accumulation may result in acute liver failure. Patients may also develop neurologic, ophthalmologic, and renal dysfunction. Fertility is generally reduced in women, but treatment with copper-chelating agents during pregnancy can result in positive outcomes for both the mother and fetus.24 Hemochromatosis is a condition of iron accumulation that results in arthropathy, skin pigmentation, diabetes, hypopituitarism, hypogonadism, heart failure, and liver cirrhosis. Phlebotomy (with or without a chelating agent) to deplete iron stores markedly improves survival and prevents most of the complications.25 α1-Antitrypsin deficiency results in uncontrolled tissue degradation, with effects predominantly in the lungs and liver. This leads to emphysematous changes in the lung as well as liver cirrhosis.26 Pregnancy can be complicated by fetal growth restriction (also known as intrauterine growth restriction), preterm labor, and pneumothorax or other respiratory decompensation.27

Hepatotoxicity

Hepatotoxicity can result from a variety of exposures. Acetaminophen (paracetamol), involved in 20% of drug overdoses during pregnancy, is metabolized by the liver into highly reactive oxides. If their formation exceeds the binding capacity of glutathione, maternal and fetal hepatic injury occurs. Treatment with N-acetylcysteine within 16 hours of acetaminophen ingestion may bind toxic metabolites in both the mother and the fetus and improve outcomes.28 Alcoholic hepatitis can result from the acute ingestion of large amounts of alcohol, and chronic alcohol ingestion may lead to cirrhosis.29 Other agents that have potential to cause hepatotoxicity during pregnancy are antiretroviral drugs for HIV infection, propylthiouracil for hyperthyroidism, alpha-methyldopa for hypertension, isoniazid for tuberculosis, statins for antiphospholipid syndrome or hyperlipidemia, mushrooms and herbal supplements, and industrial agents.30–32 In one report, liver transplantation was successfully accomplished during pregnancy to treat acquired propylthiouracil-induced hepatotoxicity.33

Liver Diseases Specific to Pregnancy

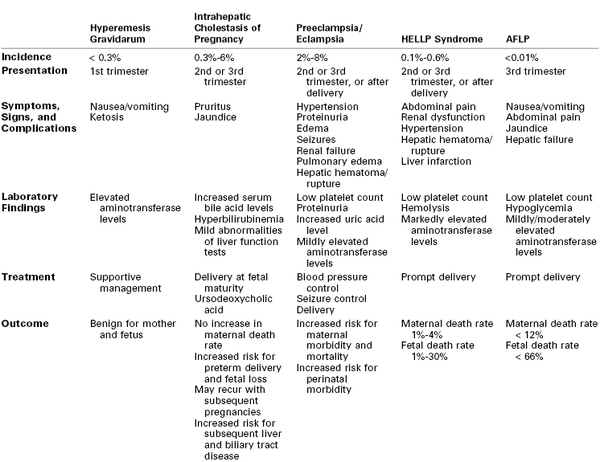

Liver diseases specific to pregnancy are summarized in Table 46-1.

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Hyperemesis gravidarum occurs in 0.3% of pregnancies and is characterized by a severe and persistent form of nausea and vomiting that can lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, as well as elevated liver transaminases, mild jaundice, and transient hyperthyroidism (see Chapter 16).34 The possible etiologies include hormonal, infectious (e.g., Helicobacter pylori), mechanical (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux), genetic, and psychogenic causes. Treatment with vitamin supplementation and antiemetics (e.g., doxylamine, metoclopramide, ondansetron) may be indicated, and severe cases may require enteral or parenteral nutrition and rehydration. Adverse pregnancy outcomes are rare but may occur in women who fail to gain adequate weight during pregnancy.

Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy occurs in less than 0.3% of pregnancies overall in the United States but in up to 6% in some (e.g., Hispanic) subpopulations. It is more common in nulliparous women with multiple gestation.35 Proposed causes include genetic mutations that alter phospholipid or bile salt transport across hepatocyte membranes, as well as abnormal steroid hormone profiles, resulting in pruritus and elevated serum bile acid levels during the second or third trimester. Pruritus is primarily on the palms and soles, is more severe at night, and may lead to excoriations resulting from scratching. Jaundice may also be present.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy has minimal impact on maternal health during gestation. However, failure to correct vitamin K malabsorption may lead to clinical coagulopathy. Fisk et al.36 reported an 11% incidence of postpartum hemorrhage among women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Although maternal outcome is generally good, the fetus is at increased risk. A study of 693 women with a diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy showed an increased risk for preterm delivery (4.3%), asphyxia events (7.1%), and meconium staining.37 Fetal complications were increased when bile acid levels were greater than 40 µmol/L.

Ursodeoxycholic acid is currently the treatment of choice until fetal lung maturity allows for early delivery.38 Antihistamines may also be used to relieve pruritus. Delivery at 37 weeks’ gestation is recommended because most fetal demise occurs with longer gestations; even earlier delivery may be warranted in cases of intolerable pruritus or previous fetal demise. Recurrence of the disease is common in subsequent pregnancies.39–41

Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP), or reversible peripartum liver failure, occurs in up to 1 per 7,000 pregnancies and is more common in twin gestations. Maternal mortality up to 12% and fetal mortality up to 66% have been reported, but with prompt and aggressive care the mortality rates can be significantly decreased.42 The disease is characterized by microvesicular fatty infiltration of the liver (and possibly kidney) believed to be due to defective beta oxidation of fat, usually in the third trimester. To date, AFLP has been documented in 30% to 80% of pregnancies in which the fetus was found to have a long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (LCHAD) deficiency. It remains unclear why only some mothers who give birth to a child with fatty acid oxidation defects develop AFLP. Multiple gestation may further stress the fatty acid oxidation capacity in susceptible pregnant women. Davidson et al.43 reported three cases of AFLP in parturients with triplet gestation.

Early symptoms are nonspecific and include anorexia, nausea, emesis, malaise, fatigue, and headache. Jaundice, edema, hypertension, hypoglycemia, diabetes insipidus, and encephalopathy may develop. Progression to fulminant hepatic and renal failure can be rapid. AFLP is commonly misdiagnosed as preeclampsia or HELLP syndrome because of a similar constellation of presenting symptoms. Similarities between AFLP and preeclampsia or eclampsia are intriguing. Both disorders primarily occur near term and are associated with nulliparity and multiple gestation.

AFLP is a medical emergency that demands rapid evaluation and treatment. Hepatic failure and fetal death may occur within days. Management includes control of hypertension, seizure prophylaxis, and immediate delivery of the fetus or termination of the pregnancy. Mode of delivery is not as critical as is doing so expeditiously.44 Liver transplantation may be indicated in severe cases. The anesthesiologist should anticipate postpartum hemorrhage, establish adequate intravenous access, and ensure that crossmatched blood is immediately available for any parturient with AFLP.45 There is often a worsening of liver function, renal function, and coagulopathy for 48 hours after delivery, followed by improvement during the subsequent weeks.39,40,44 Survivors experience no hepatic residua, and subsequent liver biopsy specimens show no evidence of fibrosis.42 Episiotomy is avoided if possible, and abdominal delivery may be complicated by wound dehiscence related to coagulopathy; delayed wound closure may be indicated.44

Spontaneous Hepatic Rupture of Pregnancy

In 2003, 150 cases of hepatic rupture in pregnancy had been published.46 Hepatic rupture may also complicate preeclampsia, eclampsia, HELLP syndrome, and AFLP. By definition, spontaneous hepatic rupture of pregnancy occurs in the absence of antecedent trauma. Instead, rupture is preceded by an intraparenchymal hepatic hematoma. The strong association with preeclampsia suggests that periportal hemorrhagic necrosis, hypertension, and coagulopathy may lead to hematoma formation. With expansion of the hematoma, the hepatic capsule is progressively distended and dissected from the parenchyma, leading to rupture.47 Primary hepatic pregnancy with embryonic implantation on the liver is another rare condition that can result in liver hemorrhage and shock. In the early postpartum period, growth of hepatic hemangiomas, adenomas, or other potentially hemorrhagic masses may occur.

The mortality rate from hepatic rupture in pregnancy is greater than 60% but may be reduced by greater awareness and improved diagnostic modalities.48 Ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, angiography, technetium scintigraphy, and exploratory laparotomy may demonstrate the expanding hematoma before rupture.49 Hematomas that are contained within the liver may be conservatively managed with intravenous fluids and blood products. More aggressive treatment options include open laparotomy, hepatic artery ligation or embolization, and compression of bleeding points with hepatic packing. Recombinant factor VIIa may be considered in the presence of intractable hemorrhage,50 and liver transplantation can be considered as a last resort.51

Liver Function and Dysfunction

Regardless of the disease state and whether it is incidental or unique to pregnancy, the signs and symptoms of acute and chronic liver diseases are similar.

Markers of Liver Dysfunction

The liver performs a variety of physiologic functions, derangements of which are characteristic of liver diseases (Box 46-1). Amino acid metabolism in the liver uses enzymes that include alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Levels of these enzymes are generally normal in pregnancy, but hepatocyte injury leads to their release (commonly called “transaminitis”) into the blood where abnormal serum levels can be detected. The liver also removes bilirubin produced from heme metabolism in the blood. Thus, liver dysfunction can lead to accumulation of bilirubin that becomes symptomatic as jaundice. Gluconeogenesis can be impaired by liver dysfunction leading to hypoglycemia and accumulation of lactate. Synthetic functions of the liver include production of albumin and coagulation factors. Although albumin concentration normally decreases during pregnancy secondary to increased maternal plasma volume, prothrombin time (PT) is unchanged during normal pregnancy; therefore, an increase in PT is an indicator of possible liver disease. Decreased thrombopoietin production in the liver, along with hypersplenism from portal hypertension, may lead to thrombocytopenia. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) are found in biliary tract cells. ALP is normally increased during pregnancy because of fetal and placental production, but an elevated level of GGT is suggestive of biliary disease. Detoxification functions of the liver are responsible for clearance of many toxic metabolites and drugs. Failure of conversion of ammonia to urea in the liver results in accumulation of ammonia and consequent encephalopathy. Decreased clearance of estrogen and progesterone with liver disease may cause hyperventilation, and other signs of a hyperestrogenic state such as telangiectases and palmar erythema, although this may occur even in normal pregnancies because of increased production by the placenta. Various antigens and antibodies also show characteristic patterns of abnormalities in autoimmune and infectious forms of hepatitis and can be used for diagnosis and treatment monitoring.22,52