Law, Quality Assurance and Risk Management in the Practice of Neonatology

Harold M. Ginzburg

Mhairi G. MacDonald

BASIC LEGAL AND REGULATORY CONCEPTS

A brief historical overview of the transition from the past to present will help explain some of the current legal and social difficulties within the practice of medicine.

Health care professionals have always been subject to punishment should their medical skills or judgment fall below a community standard. Reports from the Middle Ages in England indicate that compensation was paid when patients were injured. In other nations during the Middle Ages the health care provider, if found responsible for poor medical care, was deformed in the same manner as the injury that he caused. Physicians were not motivated to treat patients with complicated illnesses unless the patient and his or her extended family clearly understood that treatment would be palliative. Although litigation has replaced amputation in modem western societies, health care providers and institutions still practice under the specter of retribution and public criticism.

Prior to the middle of the 20th century members of the healing profession functioned as an integral part of their local community. Since the 1940s there has been a progressive separation of health care providers from the communities they serve; this process has been accelerated by the advent of highly subspecialized and expensive intensive care. Neonatologists function in a crisis environment with little or no prior knowledge of their patients’ family unit.

Isolation of patients from health care providers, except in times of crisis, can lead to poor or limited communication and unrealistic expectations. The family expects success.

Litigation may be initiated when negligence has occurred or is perceived to have occurred. A lack of good communication skills and empathy can be as self destructive as a faulty knowledge base, performing unacceptably, or functioning in an impaired manner. Thorough knowledge and understanding of one’s medical subspecialty is insufficient to prevent involvement in malpractice litigation. Impersonal institutional and individual behaviors often precipitate a lawsuit. The failure to communicate and document patient and health care system interactions may place a health care system or provider in an untenable position when his or her actions are reviewed in an arbitration, mediation, or courtroom environment.

Health care providers are never able to succeed all the time. Sometimes the nature and extent of the disease is too severe, sometimes the course of treatment is too risky or aggressive to be tolerated by the patient, and sometimes errors of skill and judgment are made. Relatively recently the medical community and their legal advisors have come to the realization that explaining to a patient and family what went wrong in language that they can understand is not only the right thing to do but also appears to decrease the incidence of litigation (1,2). As part of its accreditation process, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) now requires health care organizations to disclose unanticipated injuries to the affected patients, investigate their root causes, and take action to prevent their recurrence (3).

Responsibility and Liability

The mundane aspects of medical care and treatment, such as scheduling of appointments, documentation of procedures, and understanding of the federal, state, and local

guidelines, procedures, policies, regulations, and laws, are frequently the basis for confrontations between members of the medical and legal professions.

guidelines, procedures, policies, regulations, and laws, are frequently the basis for confrontations between members of the medical and legal professions.

The vast majority of medical education pertains to understanding basic sciences and providing clinical services. Little formal attention is given to the myriad of governmental policies, procedures, and regulations that control all aspects of health care delivery.

Medical care is a contract between the health care professional and the patient. In almost all instances, if the patient is unable, because of age or illness, to render informed educated consent, then others must provide such consent. Thus, as a patient is examined or interviewed, law and medicine become intertwined.

The basic legal considerations relating the care and treatment of any patient, and particularly, a neonate, flow from the following four concepts:

The duty to act. When does the health care professional-patient or health care facility-patient relationship commence?

Knowledge and application of hospital policies and local, state, and federal mandates. What resources are available to facilitate information transfer to health care facilities and service providers?

Responsibility and accountability of the health care provider (individual or organization) to provide adequate care and treatment. Who is responsible for the decisions made in the provision of health care? Who monitors the quality of the services provided? Who ensures that the services provided are consistent with hospital policies and local, state, and federal mandates?

Information transfer to patients and their families or guardians. Who obtains educated informed consent, in what manner, and with what documentation? Who is responsible for providing ongoing medical information to the families or guardians of neonates and ensuring that the information, and the implications of the information, is understood? State and federal legislation, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Account-ability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) (4), do not set standards for the manner in which a clinician may or should communicate with a patient, family member or significant other.

Defensive Medicine

Defensive medicine has become a medical term of art. However, it can connote a thoughtful systematic approach to health care rather than the excessive ordering of investigatory studies because of anticipatory fear of litigation for malpractice. Medical malpractice lawsuits are based on the principle of negligence. Negligence implies some wrongful act of commission or omission (5). The essence of negligence is unreasonableness.

Due Care

Due care is simply reasonable conduct (6). In order for negligence to be demonstrated in a courtroom, the injured person/plaintiff must demonstrate that (a) there was a legal duty owed to him; (b) there was a breach of that duty (a deviation from the accepted standard of care); (c) as a result of the duty and the breach thereof, damages or an injury occurred; and (d) the damages or injury can be determined to have been caused by, or shown to have flowed from, the care or lack of care provided by the health care provider and/or organization responsible for the environment in which the health care was provided.

Quality assurance and risk management aspects of medical care are relatively recent innovations designed to improve patient care and outcome; they are discussed in greater detail in the second section of this chapter. Quality assurance activities accept the legal and medical position that a health care provider owes a duty to the patient to provide reasonable medical care, consistent with available resources. There are inherent, irreducible risks in the delivery of medical care and treatment, and quality assurance and risk management assessments are designed to identify and limit the risks. There are always risks in a medical intervention, and there are always risks in not rendering a medical intervention. The balance of relative risks needs to be understood by both the health care provider and the patient and/or parent/guardian.

The Duty to Act

The duty to act is determined when the health care professional- or organization-patient relationship commences (7). A “duty” is a legal and ethical responsibility. There is no legal duty under most circumstances for a health care provider or institution to accept a patient for care unless they hold themselves out as providing emergency care or they are required to do so by law, regulation, or contract. If a medical center, hospital, or physician represents itself to the public as a source of emergency medical care and the community has come to expect such care, then a patient cannot be arbitrarily denied such services (8). Once a health care service is initiated, a health care provider/institution-patient relationship exists, a duty is created, and there is then a legal and moral obligation not to abandon the patient. Further, the care that is being provided must be adequate under the circumstances. A moral and legal obligation attaches, which precludes abandonment or “dumping” of the patient (9). A referring hospital transferring an infant to another institution for further care is not perceived as abandoning the patient, as long as the reason for transfer is medical and not financial. The senior medical person responsible for the transport, whether stationed at a hospital or directly providing patient care during transport, is deemed to be supervising the health care until the transport team transfers care to the clinical staff at the receiving referral medical facility. The transport team’s legal and ethical duty to the patient exceeds that of other parties, such as the referring or referral hospital.

The complexity of health care responsibility and liability increased rapidly during the 20th century. Public health

care facilities have existed since the Middle Ages. Commencing in the 13th century, the Hotel Dieu in Paris provided indigent care for many centuries. In the United States, city, municipal, state, and federal public hospitals provided care for those unable to obtain it elsewhere, and the physicians and hospitals were not held liable for the outcome of care that was provided free of charge. The doctrine of charitable immunity protected hospitals from legal liability if medical negligence occurred within their boundaries. However, an individual’s inability to pay for medical care no longer affects his or her ability to demand and receive services that are commensurate with those provided to patients who pay for their care directly or through third-party payment systems. Thus, providing care to patients who are unable to pay no longer protects a health care provider or medical institution from liability for negligence or malpractice. Physicians, other health providers, suppliers, and manufacturers of equipment, medical devices, and medicines can now all be sued for negligence and be held individually or jointly liable for their own actions, those that they supervise, and those that are performed by members of their health care team.

care facilities have existed since the Middle Ages. Commencing in the 13th century, the Hotel Dieu in Paris provided indigent care for many centuries. In the United States, city, municipal, state, and federal public hospitals provided care for those unable to obtain it elsewhere, and the physicians and hospitals were not held liable for the outcome of care that was provided free of charge. The doctrine of charitable immunity protected hospitals from legal liability if medical negligence occurred within their boundaries. However, an individual’s inability to pay for medical care no longer affects his or her ability to demand and receive services that are commensurate with those provided to patients who pay for their care directly or through third-party payment systems. Thus, providing care to patients who are unable to pay no longer protects a health care provider or medical institution from liability for negligence or malpractice. Physicians, other health providers, suppliers, and manufacturers of equipment, medical devices, and medicines can now all be sued for negligence and be held individually or jointly liable for their own actions, those that they supervise, and those that are performed by members of their health care team.

Licensure; Interstate-International Practice

In the United States, health care providers (physicians, nurses, emergency medical technicians, etc.) may be licensed in more than one state. They must be licensed in the state in which they maintain their primary office or place of employment. The authorities in most, but not all, states are not concerned about whether a health care provider who enters the state solely to transport a patient to another health care facility is licensed in that state; however, they are concerned that the individuals involved in the transport are competent to perform their job.

An individual who enters a state, regardless of the reason, will be subject to that state’s laws. If a driver is involved in an accident, he or she is subject to the laws of the state in which the accident occurred, not to those of the state that issued the driving license; this legal principal also applies to medical transport vehicle operators (10). Failure to obtain informed consent may result in litigation in the state in which it was inadequately obtained or in the state to which the patient was transferred.

Patients and their guardians may initiate medical malpractice litigation in the state in which they reside, the state in which the alleged negligence occurred, the state in which the hospital is located, or the state in which the physician resides. If the patient/plaintiff can show that his or her residence is in a different state from that of the defendant/hospital and defendant/health care provider, then the plaintiff can commence the litigation in a federal court because the matter involves diversity of jurisdiction, i.e., opposing parties are located in two or more states. The defendant can request that the matter be removed to the federal court system for a similar reason (11). Most plaintiffs prefer state courts, especially if the defendant is from a different state. Some state courts are known for their large awards to plaintiffs, whereas others are known to be more sympathetic to defendants/health care providers.

Telemedicine

Recent advances in telephone-linked care (TLC) or “telemedicine” (see also Chapter 5) have initiated new questions regarding the practice of medicine across state lines (12). TLC has been applied as a supplement to direct patient care, to monitor patient progress, and as a service expander for specialized medical expertise and technology (e.g., the interpretation of neonatal radiologic or cardiologic films and tracings). Landwehr and associates (13) demonstrated the feasibility of telesonography for the interpretation of fetal anatomic scans from a remote location. Lewis and Moir (14) in Scotland and Landquist (15) in Finland demonstrated that telemedicine is an international technology.

TLC has been practiced for more than 30 years (in its simplest form, it includes giving advice over the telephone). In 1996 the U.S. Congress passed the Telecommunications Reform Act, which required a study of patient safety, efficacy, and the quality of services (16). The neonatologist has the opportunity to engage in “telehealth,” which includes consultation, transportation, and interpretation of radiographic, cardiologic, and other data, as well as professional education, community health education, public health, and administration of health services. The American Medical Association and American Telemedicine Association have urged medical specialty societies to develop appropriate practice standards. Managed care organizations have begun to embrace telemedicine. Louisiana, in 1995, became the first state to enact legislation dealing with telemedicine reimbursement (17) that specifies a certain reimbursement rate for physicians at the originating site and includes language prohibiting insurance carriers from discriminating against telemedicine as a medium for delivering health care services.

California in 1996 (18), Oklahoma in 1997 (19), Texas in 1997 (20), and Kentucky in 2000 (21) have also passed telemedicine legislation. However, at the present time, issues relating to cross-state licensure are perceived to be potential barriers to the expansion of telemedicine, especially now that reimbursement is possible. States license physicians and other health care providers within their boundaries, but the federal government has the authority to prepare national licensure standards as they relate to national programs such as Medicaid and Medicare. In the future, there may be alternative approaches to licensure (22). Regardless of the end result of the issues surrounding telemedicine, neonatologists increasingly cross state and international boundaries and need to appreciate that the laws of political jurisdictions other than their home state may significantly impact the manner in which they practice.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has become involved in telehealth activities on the Internet.

Over the past few years, some Web sites have offered illegal drugs or prescription drugs based on questionnaires rather than a face-to-face examination by a licensed health care practitioner. Some offshore sites offer prescription drugs without any prescription or medical consultation. The FDA works with the U.S. National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, which created a program in 1999 called Verified Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites to provide the consumer with the ability to verify the safety of medications being sold over the Internet (23). A number of U.S. federal and state regulatory agencies are working together to address health-related consumer problems on the Internet. They include state health authorities, FDA, Justice Depart-ment, and Federal Trade Commission. The Federal Trade Commission plays a key oversight and enforcement role in Internet commerce.

Over the past few years, some Web sites have offered illegal drugs or prescription drugs based on questionnaires rather than a face-to-face examination by a licensed health care practitioner. Some offshore sites offer prescription drugs without any prescription or medical consultation. The FDA works with the U.S. National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, which created a program in 1999 called Verified Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites to provide the consumer with the ability to verify the safety of medications being sold over the Internet (23). A number of U.S. federal and state regulatory agencies are working together to address health-related consumer problems on the Internet. They include state health authorities, FDA, Justice Depart-ment, and Federal Trade Commission. The Federal Trade Commission plays a key oversight and enforcement role in Internet commerce.

Medical Torts and Contracts

The legal system is divided into two broad areas. Civil litigation is based on the need to correct or remedy a wrong between one individual (corporation or partnership) and another. Criminal prosecution is instituted to correct a wrong against the community. In a civil litigation matter (or case), the plaintiff is the party bringing the lawsuit and alleging the wrong; the lawsuit is filed against the party (defendant) who is accused of causing the damage. In a criminal prosecution, the plaintiff is the government (local, state, federal) alleging that the community has been harmed by the action or inaction of a party (also known as the defendant).

Civil matters resulting in litigation generally are either contract disputes or torts. A contract dispute occurs when two or more parties have entered into an agreement and one or more parties believe that the terms and conditions of the agreement, either an oral or written contract, have not been met. It is important to appreciate that, in a court; most oral contracts have the same weight as written contracts.

A personal tort is an injury to a person or his or her reputation or feelings that directly results from a violation of a duty owed to the plaintiff (in medical malpractice cases, this is usually the patient) and produces damage. The remedy in any civil matter, after the nature and extent of the damages have been proved to the court (a judge with or without a jury), is determined by a preponderance of the evidence (more than 50.01%). Thus, to a medical degree of certainty means that it is more likely than not, and it is that standard upon which there are usually monetary damages awarded if the matter is found in favor of the plaintiff. In most instances in the United States, each side pays for its own legal services, regardless of the outcome of the case.

Battery

Battery is a tort; it is an intentional and volitional act without consent which results in touching that causes harm (e.g., the touching of a patient’s body without consent). A technical battery can occur when there is no actual harm but touching occurred without consent. Patient care, even with a beneficial outcome but without informed consent, may be considered battery.

Plaintiffs may sue for an injury that occurred as a result of negligence or a tort (physical or mental harm), or both. Because the criminal court usually will not award monetary damages to the victim of a crime and because the standard of proof for conviction is “beyond a reasonable doubt” (quantitatively, this can be conceptualized as at least 95% certain), plaintiffs usually prefer to sue for injuries from a tort in civil court. In civil litigation, monetary damages may be awarded, and if the injury was determined to be egregious, punitive damages also can be assessed against the defendant. The standard of proof in civil litigation is the “preponderance of the evidence” or the “more likely than not” standard; it is a “superiority of weight” test that requires that for the plaintiff to be successful, 50.01% of the evidence must weigh in his or her favor (24). Thus, the preponderance of the evidence rule is a threshold test (25). In general, either the plaintiff proves that the damages were more likely to have been caused by the defendant agent than by any other source and is; therefore, entitled to full compensation, or he or she fails to meet the burden of proof and is entitled to nothing (26).

Professional Negligence

Negligence is “conduct, and not a state of mind” (27), “involves an unreasonably great risk of causing damage” (27) and is “conduct which falls below the standard established by the law for the protection of others against unreasonable risk of harm” (28,29).

Professional negligence, or medical malpractice, is a special instance of negligence. The medical profession is held to a specific minimum level of performance based on the possession, or claim of possession, of “special knowledge or skills” that have been accrued through specialized education and training.

Ely and associates (30) found that when family physicians recalled memorable errors, the majority fell into the following categories: physician distracters (hurried or overburdened), process of care factors (premature closure of the diagnostic process), patient-related factors (misleading normal results), and physician factors (lack of knowledge, inadequately aggressive patient management). Under-standing the common causes of errors alerts the practitioner to situations when errors are most likely to occur.

The Elements of a Malpractice Case

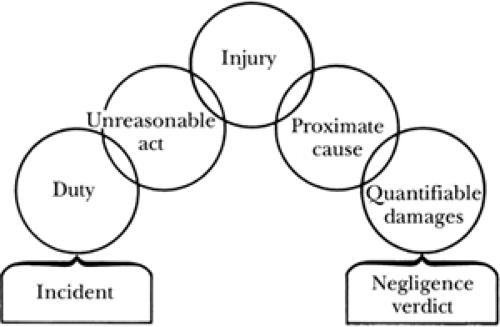

To establish a prima facie medical malpractice case (one that still appears obvious after reviewing the medical evidence), the patient/plaintiff must demonstrate (Fig. 8-1): that (a) there is a duty on the part of the defendant/health care provider and/or defendant/health care facility to the patient/plaintiff, (b) the defendant failed to conform his or her conduct to the requisite standard of care required by the relationship, and (c) an injury to that patient/plaintiff resulted from that failure (31).

Generally, in order for the plaintiff to establish a claim of medical malpractice, the plaintiff must establish by medical expert testimony (a) what the applicable standard of care is, (b) how the defendant breached or violated that standard of care, and (c) that the breach or violation (also referred to as the negligence) was the proximate cause of the injury.

A medical malpractice action can only proceed if the court determines that there is a genuine issue of material fact and if damages are quantifiable (e.g., the future costs of treatment, economic lost value of productive activities, etc.).

The most difficult element to prove is whether or not the standard of care was adequate. The plaintiff usually must provide expert witnesses to establish what a prudent health care provider in similar circumstances might have done. A “conspiracy of silence” may have existed in prior years in the United States, but today there are many “experts” willing to testify anywhere about anything. However, in Japan and other nations, it is difficult to find a local or even national expert to testify in medical malpractice cases (32).

More than 100 years ago in Massachusetts, it was held that a physician in a small town was bound to have only the skill that physicians of ordinary ability and skill in similar localities possessed. The court believed that a small-town physician should not be expected to have the skill of surgeons practicing a specialty in a large city (33). It was also held that a physician was required to use only ordinary skill and diligence, the average of that possessed by the profession as a body, and not by the thoroughly educated (34). However, a physician is now not excused for failing to keep himself or herself informed of medical progress. State requirements for continuing education and the effects of telemedicine consultations and educational programs essentially have removed clinicians’ ability to say that they are too busy or so geographically inaccessible as to be precluded from keeping current with new treatments and new understanding of the illnesses that affect their patients.

Courts admit medical evidence based upon rules of evidence. In 1993, the U.S. Supreme Court in Daubert v Merrill Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ruled that the Federal Rules of Evidence standards for acceptance of evidence would be used (35). This was an attempt to remove junk science from distracting the jury. The court held that scientific (medical) evidence had to be grounded in relevant scientific principles. The four criteria the court established are: (a) whether the theory or technique has been tested; (b) whether the theory or technique has been subjected to peer review and publication; (c) the known or potential rate of error of the method used and the existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique’s operation; and (d) whether the theory or method has been generally accepted by the scientific community. Thus, publication in a peer-reviewed or peer-refereed journal was not the only qualification for acceptance of evidence in a courtroom. The district (trial) court judges have the latitude to permit or exclude experts, based on the perceived scientific merit of the information they intend to provide to the court and, thus, to the jury. The fundamental issue for a clinician is not an understanding of the rules of evidence and the workings of the civil justice system but practicing medicine and acting in a professional manner, as documented in a patient’s medical record.

Many states have medical peer-review panels in place. In these states, before a medical malpractice case may be heard in a court, the facts of the case are presented to the review panel on behalf of both the plaintiff and defendant. The medical facts often are buttressed by the opinions of retained medical experts for both sides. In some states the medical review panel is comprised of attorneys and physicians; in other states the medical review panel is chaired by an attorney and comprised of physicians in the same or similar medical specialty as the physician being accused of having committed malpractice. Even when there is a finding for the defendant by the medical review panel, the plaintiff may continue litigation in the local court. However, the findings of the medical review panel are admissible on behalf of either the plaintiffs or defendants.

Res ipsa loquitur

There are circumstances in which no expert witness is required to corroborate the findings of negligence. The doctrine of res ipsa loquitur essentially means that the thing speaks for itself. Under such circumstances, the negligence is inferred from the act itself, i.e., proof from circumstantial evidence. In the classic case Ybarra v Spangard, a patient was well prior to being anesthetized for an appendectomy, and when he woke up he had an injury to his arm (36). Clearly, he could not determine how his arm was injured; the operating room and recovery room staff either could not or would not explain the etiology of the injury. The court found for the injured plaintiff without the introduction of any expert witnesses because (a) the plaintiff had not done anything that in any way could have contributed to the injury, (b) the injury could not have occurred unless someone

was negligent, and (c) the instrumentalities (hospital staff and physicians) that allegedly caused the injury were at all times under the control of the defendant hospital.

was negligent, and (c) the instrumentalities (hospital staff and physicians) that allegedly caused the injury were at all times under the control of the defendant hospital.

Informed Consent

Informed consent requires that sound, reasonable, comprehensible, and relevant information be provided by a health care professional to a competent individual (patient or guardian) for the purpose of eliciting a voluntary and educated decision by that patient (or guardian) about the advisability of permitting one course of clinical action as opposed to another (28). Physicians and other health care providers are held to have a fiduciary duty to their patients. Such a duty exists when one individual relies on another because of the unequal possession of information. The failure to obtain proper informed consent may result in the defendant/physician or defendant/hospital being sued for battery in some states or for negligence in others.

According to the battery theory, the defendant is to be held liable if any deliberate (not careless or accidental) action resulted in physical contact. The contact must have occurred under circumstances in which the plaintiff/ patient did not provide either express or implied permission and the defendant/health care provider knew or should have known that the action was unauthorized. If the scope of consent obtained from the patient is exceeded, a claim of battery is proper. The plaintiff in Mohr v Williams consented to have surgery performed on her right ear (37). During the procedure, the surgeon determined that the right ear was not sufficiently diseased to require surgery, but the left ear required surgery. Because the patient was already anesthetized, the surgeon performed the operation. The operation was a success, but the patient successfully sued for battery. The court held that there was no informed consent for an operation to the left ear. Thus, it is not necessary for injury to occur for damages to be awarded; demonstration that there was unauthorized touching is sufficient. In this instance, the court found that there was no medical emergency that would have threatened the plaintiff/patient if the surgery had not immediately commenced. If there were evidence of a medical emergency, the court’s decision might have been significantly different.

Failure to specifically identify the risks that accompany a surgical procedure also can result in a successful claim of battery. In Canterbury v Spence, the plaintiff/patient successfully proved that he was not informed of the risks attendant to the surgical procedure and that had he known them he would not have given permission (38). The court held that the physician has a duty to disclose all reasonable risks of a surgical procedure, and because he failed to perform that duty, the court held him liable for damages to the patient. The court noted that the concept of informed consent might be more appropriately replaced with the concept of educated consent. The court also articulated an objective standard that could be used in legal cases involving informed consent. This objective standard is based on what a reasonable person in circumstances similar to that of the patient would have decided if he or she had been provided with an adequate amount of information. Therefore, the central issue in a medical battery is whether an educated, effective, or valid consent was given for the procedure that actually was performed.

A physician is not required to disclose every possible risk to a patient for fear of being guilty of battery (39). The court in Cooper v Roberts held that “[t]he physician is bound to disclose only those risks which a reasonable man would consider material to his decision whether or not to undergo treatment” (40). Thus, the court stated that such a standard creates no unreasonable burden for the physician. However, the physician must disclose risks that are material and feasible alternatives that are available. The information should be provided in a language and manner that reflects the emotional and educational status of the patient or, when the patient is a neonate, the parents. In Davis v Wyeth, the court held that any medical complication or risk that has a probability of greater than 1:1,000 should be included in the informed consent (41).

When a therapeutic procedure is for the benefit of a minor, the decision to proceed usually belongs to the parent or legal guardian. The failure of the parent to consent to blood transfusions (even if the refusal is based on sincere religious convictions) or other now routine procedures for a small child that are clearly medically indicated and required for the maintenance of life can be overridden by the physician and/or hospital petitioning the court for the appointment of a temporary legal guardian (42).

The unavailability of a parent in a life-threatening circumstance should not preclude therapeutic action. Just as informed consent is imputed to an unconscious accident victim who has a life-threatening condition that requires surgery, such rational behavior can be imputed to the absent parent in the case of a sick neonate. However, in such circumstances if time permits, detailed documentation and consultation with the hospital administration is recommended.

Informed consent in neonatal/perinatal medicine is not an empty gesture to reduce liability, but rather an interaction with the physician that helps parents to become full partners in decision making. Informed consent documents are intended to support decision makers in their choices, rather than to merely have them ratify decisions already made (43). Informed consent documents need to be routinely reviewed to determine that the reading level required to understand them is consistent with the educational and cultural experiences of those being asked to read, understand, and sign the forms (44).

The informed consent process can be extremely complex, with several legal “gray areas.” For example, are maternal rights any more definitive in making critical decisions for a fetus or neonate than paternal rights? Conflicts can arise even when the putative or alleged father is not the legal spouse of the mother. Emergency hearings in front of local judges may be required to resolve conflicting opinions, especially when the decision of one parent may lead,

to a medical degree of certainty (more likely than not), to the death of the infant.

to a medical degree of certainty (more likely than not), to the death of the infant.

It is one of the ironies of the law, in most states, that an unwed teenage mother has the ultimate legal responsibility for the care of her child, unless the court is petitioned to appoint an alternative guardian. In many states the live birth of a child, regardless of the age of the mother, results in the mother being declared an emancipated minor. In contrast, a non-pregnant teenager, living at home and attending school, does not have the legal right to make decisions about many aspects of her own medical care.

The disclosure of risks in the informed consent process tends to underscore a parent’s sense of helplessness and to portray the physician as somewhat helpless as well. The powerlessness of the parents and their wish that the physician be omnipotent creates unrealistic expectations for the outcomes of procedures and treatment. Gutheil and associates (45) suggest that the physician acknowledge the parent’s wish for certainty and substitute the mystical with a physician-parent alliance in which uncertainty is accepted.

Advanced Care Planning

Decision making in life and death situations is not easy. Advanced care planning efforts initially evolved in the care of the elderly (46). Advanced care planning, or contingency medical care planning, is no longer generally reserved for adults. The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee of Bioethics developed a policy statement about parental permission and informed consent (47). A distinction is made in this public policy statement and in case law in the United States between emergency medical treatment, life support efforts, and elective surgical procedures, such as circumcision or removing a kidney from one child to aid a sibling (48,49). Neonates need others to make decisions about their treatment and viability. Their treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is also never a series of leisurely scheduled elective procedures. There must be a designated person to whom the health care providers relate and who is held to render decisions about treatment. When potential conflicts in decision making are recognized, a conference among the concerned individuals, with representation from the hospital administration, may be a worthwhile endeavor to clarify who actually has the final decision-making authority. There may be times in the treatment of a patient when one person has to render an immediate decision, even if that decision is not a consensus. Decision-making issues are often confounded when the mother of the neonate is an adolescent herself and not wed to the father.

While all 50 states in the United States and the District of Columbia have passed legislation on advance directives, reinforcing the fact that adherence to such directives is mandatory rather than optional continues to be problematic (46). The majority of states do place restrictions on proxy decision making. If identification of the responsible party for decision making is not clear or keeps shifting, legal consultation, initiated by the health care providers, is recommended. Most jurisdictions have the ability to hold emergency judicial proceedings when an impasse has been reached and a medical decision must be made before irreversible damage or death to the patient occurs (42).

Medical Records

As evidenced by HIPAA (4) and state regulations, medical records are legal documents. Medical and hospital records are designed to be a contemporaneous record of the available clinical information and medical and other decisions that flow from the clinical information and interactions with the patient’s significant others. Records provide an opportunity for adequate documentation. Documentation is the key to management of patients, and it is the key to protecting physicians against malpractice litigation, especially in the instances in which the patients have difficult and complex clinical presentations. The course of treatment and meeting or failing to meet therapeutic goals should be noted in the hospital chart. Treatment options, including the option of no treatment when pertinent, should be explained to the patient’s family and, if necessary, others potentially involved in the decision-making process; these interactions should be documented in the patient’s chart. The patient’s family’s understanding, or lack thereof, of the various treatment options also should be noted, especially if there are divergent views among family members. Ultimately one family member or guardian has to be acknowledged by the family and health care providers as the decision maker. Identifying such an individual in the medical record will facilitate treatment decisions and posthospital treatment care and management. Such documentation may preclude the need for judicial intervention.

Adequate medical records will document that the risks of a given procedure have been shared with the patient’s decision makers. A record that indicates that specific known adverse side effects, or rare but serious untoward events, were discussed with a patient’s family members or guardians helps protect the clinician should one of these untoward events actually occur. No medical procedure is risk free, and although families may be informed of the relative risks of the various procedures and pharmacologic interventions, the stress of the moment may shorten their attention span, concentration, and recall. For example, prescriptions at the time of discharge are often for a limited period of time, with follow-up care being provided in either a hospital outpatient, clinic, or private clinical environment. Prescriptions must be written clearly, identifying the patient, date, dose, dose schedule, and route of administration. The parent or guardian to whom the prescription is provided needs to understand why the medication is being prescribed, adverse side effects, therapeutic effects of the medication, and consequences to the infant if the medication is not provided. Medical record documentation, including discharge instructions and prescriptions, at least provide a contemporaneous record of what information actually was provided.

Medical records provide the basis for reimbursement of the costs for patient care and treatment. The severity of a condition, justification for laboratory and other investigations, need for consultations, and manner in which the consultative advice is incorporated into patient care should be present within a patient’s medical record. In the spring of 1998 the U.S. Justice Department announced the hiring of 250 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents for the purpose of investigating Medicare and Medicaid fraud. The U.S. federal government continues to pay increasing attention to the issue of fraudulent billing for health care services whether the care is provided directly or via telemedicine. The FBI estimates that 10% of the money paid out for health care services under the Medicaid program is the result of fraudulent billing (50). Not all the money paid for fraudulent services is recovered. However, in 2002, $1.6 billion was collected in connection with health care fraud cases and matters (51). The absence of consistent, comprehensive reimbursement policies is frequently cited as one of the most serious obstacles to total integration of telemedicine into health care practice. This lack of an overall telemedicine reimbursement policy reflects the multiplicity of payment sources and policies within the current U.S. health care system.

Adequate documentation facilitates medical audit, permits those who prepare invoices for reimbursement or payment to justify the categories or International Classifica-tion of Diseases codes placed on the universal billing forms (sometimes identified as HCFA-1500 forms), and prevents errors that may result in the appearance of fraud (52).

Medical Confidentiality of Oral and Handwritten Communications

The Hippocratic oath states, in part, “Whatever, in connection with my professional practice or not in connection with it, I see or hear, in the life of men, which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge, as reckoning that all should be kept secret” (53). This oath, taken by many physicians upon graduating from medical school, has been codified by state and federal law. The confidentiality of the information obtained by the physician is considered to be “privileged” (54). The privilege, however, belongs to the patient or his or her guardian; it does not belong to the physician or other health care provider. A court may order a health care provider to breach medical confidentiality; legislation may require it.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree