Laparoscopic Resection of Ovarian Endometrioma

M. Jonathon Solnik

Ricardo Azziz

INTRODUCTION

Surgical management of endometriosis ultimately depends on the desired therapeutic goals. It becomes important to establish whether relief of pain, treatment of subfertility, or both are patient priorities. Preservation of fertility would lead one to avoid overly aggressive excisional treatment, which may result in decreased ovarian reserve or increased postoperative adhesion formation. Likewise, patients with pain due to fibrotic endometriosis may require more aggressive treatment with resection of all palpable and visible disease regardless of fertility.

Resection of ovarian endometriomas represents another aspect of surgical care, and often presents itself in the setting of subfertility. Historically, most women noted to have lesions suspicious for endometrioma on transvaginal ultrasound were offered ovarian cystectomy as a part of the treatment paradigm for subfertility. Most recent findings suggest that aggressive surgical management, particularly for smaller cysts (<5 cm), may be deferred in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization.

Studies which have addressed postoperative ovarian reserve, whether resulting from the endometrioma itself or from the resulting ovarian injury following surgery, and response to gonadotropin stimulation, do not necessarily favor surgery. That said, for larger lesions, in symptomatic patients, or if a malignancy cannot be excluded, surgical intervention remains the standard of care. It has been well established that complete enucleation and cystectomy rather than ablation of cyst wall, results in significantly fewer recurrences and is the procedure of choice. Hence simple drainage of endometriomas should be avoided because the recurrence rate is high.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

As with any woman who has a documented pelvic mass, differential scenarios should be considered. The likelihood of uncovering a reproductive cancer in a young woman is relatively low, and hallmark ultrasonographic characteristics of an endometrioma are fairly consistent. Nevertheless, if there is any suspicion of a malignancy, the possibility that an oophorectomy may be required needs to be discussed during preoperative counseling. In fact, during any procedure that involves adnexal structures, especially when fertility is a primary objective, we find it equally important to review this possibility, as well as the possibility of decreased ovarian reserve even if the ovary is salvaged.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

1. Port and instrument placement: Initial port placement depends on the location and size of the endometrioma. For example, if there is a larger (>10 cm) lesion on the right, one could consider a left upper quadrant entry point in order to avoid inadvertent penetration of the lesion. We typically use a modified Hasson technique to gain peritoneal access through the umbilicus. This allows

for a larger fascial defect not provided by current fiber-spreading bladeless trocars to allow for easier retrieval of larger specimen.

for a larger fascial defect not provided by current fiber-spreading bladeless trocars to allow for easier retrieval of larger specimen.

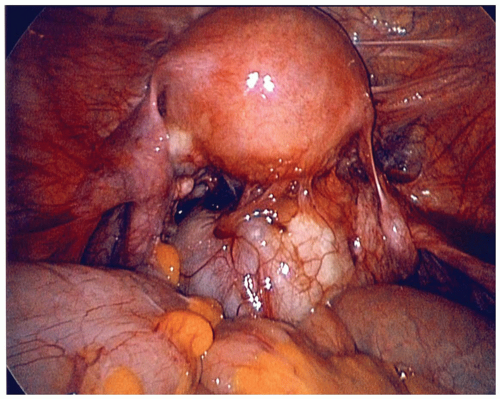

2. Mobilization of endometrioma: The resection of an endometrioma may be complicated by longstanding inflammation and resultant fibrosis, predisposing to ovarian injury and bleeding, which may require use of energy modalities to establish hemostasis, resulting in further damage to ovarian epithelium. Likely due to the pathogenesis of endometrioma, these cysts are often densely adherent to their ipsilateral sidewalls, where the peritoneal lesion infiltrated the developing follicle on the medial aspect of the ovary.

Reestablishing the normal anatomic orientation and landmarks should be the initial step in the dissection of endometriomas, particularly if sigmoid colon or other adhesions are present. The first step is often to elevate the ovary and cyst anteriorly while hugging the peritoneum of the ovarian fossa with a blunt grasper, suction irrigator, or blunt-tip scissor tips (Figures 30.1 and 30.2).

If remaining in the proper surgical planes, the surgeon will avoid entry to retroperitoneal spaces and injury to the ureter or larger vessels. Use of blunt-tip scissors to divide more dense adhesions may be required. Small bleeding and oozing may be encountered, but often stops without additional effort. Extra-ovarian adhesions are often due to endometriosis-associated inflammation. Copious irrigation, ideally with warmed isotonic irrigant, helps visualize the planes of dissection. Incidental cyst rupture often occurs during these efforts to expose the ovary in full.

3. Removal of the endometrioma: Once the ovaries have been carefully inspected and visualized, small surface endometriomas (<1 cm) can be “decapitated” at the ovarian endometrioma junction and the base coagulated or vaporized. The resulting defect does not need to be reapproximated. Alternatively, larger endometriomas are resected in a manner similar to that used at laparotomy. However, when they become particularly large (>10 cm), managing them at laparoscopy may prove difficult and should only be approached by those who have specific surgical expertise.

Once adequately mobilized, the cyst, if it has not already spontaneously drained, may be opened, drained, and lavaged. The lining is inspected. With larger or more chronic cysts, the cyst wall and ovarian cortex are often fused extensively by fibrosis and significant resection of the fused pseudocapsule may be required in order to clearly expose the plane between the normal ovarian cortex and the cyst wall. In order to identify the proper plane of dissection, the edge of the cyst wall opening is circumferentially (Figure 30.3A) cut back to fully and clearly expose “the cyst wall-ovarian cortex interphase.” This is preferably done with cold scissors since electrosurgery, ultrasonic energy, or lasers may tend to fuse the cortex and ovarian cyst wall. If the dissection plane is not developed well, attempted cyst enucleation may result in unwanted bleeding during the enucleation of the cyst.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree