Fig. 26.1

Typical involvement of the scalp by LCH in a young child, showing an erythematous plaque with significant desquamation and scaling

Children under 3 years of age are more likely to present with acute disseminated disease, usually involving bones and skin, and risk organs such as liver, spleen, and the hematopoietic system . In older children, the presentation tends to be more indolent, usually involving bones only, and indeed, patients may go for years without a diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

LCH can be a challenging diagnosis to make, since the disease has such heterogeneous presentations, may affect many different organs, and can emulate the appearance of many other diseases (infectious, inflammatory, and neoplastic). The following Table 26.1 lists diagnoses, by type, in the differential diagnosis for common presentations of head and neck LCH in children.

Table 26.1

Differential diagnosis of head and neck LCH in children

Histiocytoses | Malignancies | Other |

|---|---|---|

Erdheim–Chester disease | Lymphoma | Eczema |

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome | Germinoma | Vasculitis |

Rosai–Dorfman disease | Glioma | Otitis media/externa |

Juvenile xanthogranuloma | Primitive neuroectodermal tumor | |

Rhabdomyosarcoma |

Diagnosis and Evaluation

Physical Examination

Bony lesions usually manifest as a tender, raised, soft mass.

Cervical lymph nodes are most often soft and matted on palpation, and are usually associated with bone involvement.

Thorough skin examination is necessary to look for cutaneous manifestations [14].

Laboratory Data

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential; bone marrow aspirate and biopsy should be performed as well if there are signs of hematopoietic dysfunction [22].

Electrolytes, liver function tests, renal function tests, and protein and albumin.

If DI is suspected, a water restriction test should be performed .

Imaging Evaluation

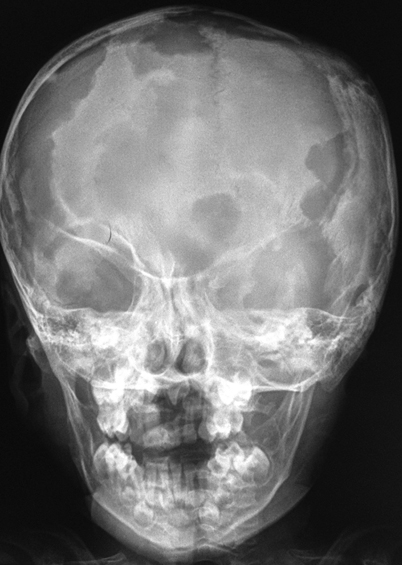

A “punched-out” osteolytic lesion, with indistinct margins, is typical [14]; there is sometimes an accompanying mass (Fig. 26.2).

Fig. 26.2

Plain X-ray of a child with severe involvement of the skull with multiple lytic lesions

CT of the head and neck to further characterize involvement of these tissues.

MRI with contrast for all patients with DI or other signs and symptoms suggestive of CNS involvement or risk (multisystem disease and/or involvement of the sphenoid, orbital, ethmoid, zygomatic, or temporal bones at diagnosis) [23] (Fig. 26.3).

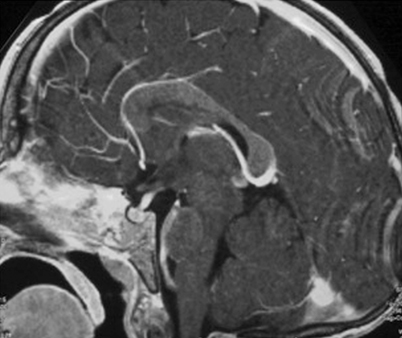

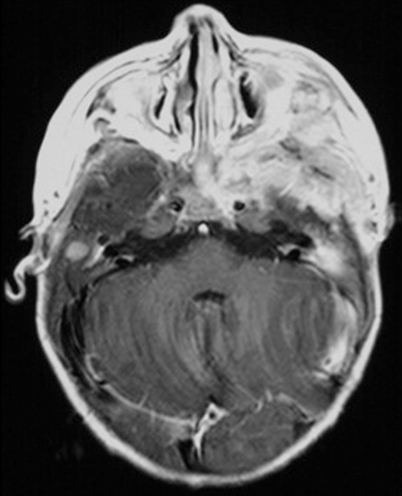

Fig. 26.3

MRI performed at the time of diagnosis in a child with severe involvement of the skull base with intracranial extension

Middle ear erosion extending to the posterior and lateral semicircular canals is a typical CT finding of temporal LCH [14].

LCH generally appears iso- or hypointense on T1, with marked contrast enhancement, and hyperintense on T2 images [27].

A full skeletal screening should be performed to investigate other sites of bone involvement. A skeletal survey is recommended, along a nuclear medicine scan (PET or bone scan).

Pathology

Since pathologic Langerhans cells activate other immunologic cells, microscopic examination of diseased tissue shows eosinophils, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes in addition to Langerhans cells; this appearance is what has been traditionally described as eosinophilic granuloma . Abscesses and necrosis may be present. Pathologic Langerhans cells are large, oval in shape, and mononuclear, with a prominent nucleus and eosinophilic cytoplasm. They do not have dendritic cell processes like cutaneous Langerhans cells . They stain positive for protein S-100, CD1a, and CD207 (langerin) and contain cytoplasmic rod-shaped inclusions called Birbeck granules as revealed by electron microscopy. A diagnosis of LCH is done by the characteristic histopathology and immunoreactivity for CD1a or CD207 in the large mononuclear cells (Fig. 26.5).

Fig. 26.5

a Characteristic histopathology with an infiltrate of mixed inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils (arrowhead), and large histiocyte-like Langerhans cells with prominent cleaved nuclei, single nucleolus, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (arrows). b CD1a membranous and Golgi immunoreactivity highlights the Langerhans cells

Treatment

The treatment of LCH over the years has reflected the changing concepts of the disease process. Indeed, the difficulties in developing more effective therapies are linked to the deficiencies in the understanding of the pathogenesis of LCH. Treatment for patients with LCH is currently risk-adapted.

Patients with single-system disease confined to a single site usually require only local therapy or observation. Patients with more extensive disease (multiple bone lesions or multiple lymph nodes) usually require systemic therapy. The best therapeutic option in these cases has not been defined, and responses have been observed with short courses of steroids with or without the addition of chemotherapeutic agents. The treatment recommended by the Histiocyte Society for this group of patients includes a 6-week induction with prednisone and vinblastine, followed by continuation treatment with pulses of the same agents every 3 weeks. The prognosis for this group of patients is usually excellent, although approximately 30 % of the patients will experience disease reactivations that continue to respond to treatment.

For patients with multisystem disease, the treatment currently recommended by the Histiocyte Society is a 12-month regimen with prednisone and vinblastine, with an early switch to more intensive nucleoside analog-based regimen in patients with slow response. Involvement of the risk organs carries the worst prognosis. This high-risk group of patients is characterized by early age at presentation (usually < 2 years), and different degrees of liver, spleen, hematopoietic, and lung involvement . Patients respond poorly to treatment, and mortality rate is approximately 40 %. Thrombocytopenia and hypoalbuminemia are particularly poor prognostic signs, conferring a 5-year survival rate of less than 20 % [28].

Surgical Therapy

Curettage alone is considered curative in patients with single skull lesions of the frontal, occipital, or parietal bones [29]. Complete resection of a unifocal bone lesion may not be necessary and may lead to deformity [30]. Injection of intratumoral methylprednisolone may be useful as an adjunct [31, 32].

Surgical removal only is also the standard of care for patients with single lymph node involvement.

For patients with involvement of the sphenoid, orbital, ethmoid, zygomatic, or temporal bones, skin, or more than one lymph node, surgical resection is usually not recommended, and patients should be treated with systemic chemotherapy. Importantly, chemotherapy in these patients usually achieves long-term control, and additional surgery or radiation therapy are not required.

For CNS LCH with mass lesion, resection is usually not indicated; these patients are also treated with chemotherapy, usually with agents that cross the blood–brain barrier, such as cytarabine or cladribine.

Surgical resection is the standard for single skin lesions, but in the case where full resection would be mutilating, topical treatment with steroids or chemotherapy is possible [30].

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is generally avoided in LCH due to its known side effects and the favorable prognosis of this entity.

Radiation therapy has been used in the past for the treatment of CNS mass lesions, although its benefit is unclear and currently it is not recommended [34].

Outcomes

Outcome After Surgery

Patients with single site disease who qualify for surgical treatment alone have excellent outcomes. However, disease reactivation (usually at other sites) occurs in approximately 30 % of the cases.

Outcome After Nonsurgical Treatments

Induction chemotherapy with vinblastine and prednisolone is generally administered for 6 weeks in all LCH patients requiring chemotherapy [39]. The response to treatment after 6 weeks is important and helps determine subsequent therapy. Evaluation at this stage should include MRI and PET.

The most recent clinical trials suggest that lower recurrence rates can be achieved by extending subsequent maintenance chemotherapy to a total treatment duration of 12 months. Patients without risk-organ involvement can continue on vinblastine and prednisolone; patients with risk-organ involvement likely benefit from the addition of mercaptopurine to the maintenance regimen [40].

The use of cladribine for DI caused by LCH involvement of the pituitary has not been shown to reverse the DI [24].

Patients with LCH causing DI have a 54 % 10-year risk of growth hormone deficiency and a 76 % 5-year risk of radiologic neurodegeneration; these also do not resolve with treatment, but chemotherapy in patients with DI alone may prevent progression to these conditions [30].

Cladribine has also been shown to achieve partial responses or stabilization of CNS LCH manifesting as mass lesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree