CHAPTER 16 Labor and Birth

FACILITATING LABOR: INDUCTION, AUGMENTATION, AND DYSFUNCTIONAL LABOR

Labor induction refers to the medical stimulation of contractions prior to the onset of spontaneous labor to cause labor to commence.1 One of the most commonly performed obstetrical procedures in the United States, rates of labor induction more than doubled between 1990 and 1998 from approximately 9.5% to 21%.2,3 Reasons cited for this increase include widespread availability of cervical ripening agents, convenience to physicians, pressure from patients, and medico-legal constraints.4 In spite of obstetric recognition that normal human gestation is 40 to 42 weeks (postterm pregnancy is defined as pregnancy past 42 weeks gestation), conservative obstetric practice frequently results in the suggestion, admonition—or insistence—by medical practitioners that their pregnant patients begin labor at, or close to, 40 weeks gestation. Data to support or refute the benefits of elective inductions are limited.4 Risks to the mother and fetus include those related to the medications used, risks of iatrogenically induced prematurity, and the increased risk of operative delivery, which is more likely to occur as a consequence of labor induction.5 According to a Cochrane review of outcomes of labor induction of fetal/neonatal death compared with awaiting spontaneous labor, or a policy of induction after 41 weeks gestation, including a total of 19 trials and over 8000 women, it was reported that there were intranatal and neonatal deaths when a labor induction policy was implemented after 41 completed weeks or later. However, such deaths were rare with either policy.6 In a matched cohort study of 7683 women with elective induced labor compared with 7683 women with spontaneous labor, from 1996 through 1997, cesarean section rates (9.9% vs. 6.5%), instrumental delivery (31.6% vs. 29.1%), epidural analgesia (80% vs. 58%), and transfer of the baby to the neonatal ward (10.7% vs. 9.4%) were significantly more when labor was induced electively.5 Studies from the United States have reported similar findings, with a doubling of operative delivery with induction. 7 8 9 10 Nulliparous women are especially at risk of cesarean section as a result of induction, and an unfavorable cervix at the time of induction appears to be the greatest contributing cause to need for operative delivery.1,7 Elective induction leads to an estimated 12,000 excess cesarean sections per annum at a cost of over $100 million.1 Overall, it is advisable to avoid elective induction unless medically indicated.10

Labor induction should only be undertaken when the benefits to either the mother or fetus outweigh the risks of maintaining the pregnancy.1 Accepted indications for labor induction include:1

Contraindications to labor induction include:1

Labor augmentation refers to the use of medications to stimulate contractions in an already commenced labor when contraction rate or intensity is inadequate to accomplish birth of the baby, or labor has slowed or stopped. Methods of augmenting labor commonly employed by medical professionals include administration of Pitocin via IV drip and artificial rupture of membranes (AROM). Dysfunctional labor is failure to progress in the presence of a normal labor pattern, or the contraction pattern itself may be uncoordinated, leading to ineffectual labor. The results are protracted, stalled, or obstructed labor. Factors contributing to dysfunctional labor include but are not limited to pelvic abnormalities, fetal malpresentation, macrosomic fetus, and maternal sedation.

MEDICAL APPROACHES TO LABOR INDUCTION AND AUGMENTATION

Oxytocin Induction

Synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin) is one of the most commonly used and most potent uterotonic agents available. It is given intravenously for purposes of induction (as an antihemorrhagic, it may be given intramuscularly), in the form of an infusion pump that allows exact dosing with various dosing protocols. Dosing is done incrementally, starting with small amounts and increasing until contractions come at 2- to 3-minute intervals, and typically not exceeding 40 mU/min. Oxytocin is more effective when administered in the presence of a ripened cervix (softening and ability to stretch), thus methods to induce ripening (i.e., prostaglandins suppositories or oral administration, cervical manipulation, amniotomy) may be used just prior to or in conjunction with oxytocin administration. Oxytocin use alone is less effective than prostaglandins for inducing labor. Labor induction with oxytocin is associated with an increased rate of cesarean section.11 Any agent that increases uterine contractions can lead to hypercontractility of the uterus, and can interfere with blood flow to the uterus, and consequently the fetus, with ensuing fetal distress.12 This is a less frequent complication with oxytocin than with misoprostol (see the following). There is some evidence to suggest that use of oxytocin may be associated with an increased incidence of fetal hyperbilirubinemia; however, it is unclear whether this is a direct result of oxytocin use, or associated with other pregnancy factors, such as preterm labor.12

Stripping the Membranes

Stripping the membranes, also called “sweeping the membranes,” is thought to release prostaglandin F2-alpha from the decidua and membranes, or prostaglandin E2 from the cervix, causing cervical ripening and instigating contractions. It is widely used by obstetricians and midwives, often done as a routine part of vaginal and cervical exams in women who are close to or past term, but often undocumented—possibly because it is not generally thought of as an invasive technique by many practitioners (although many midwives do consider it invasive, especially when done without the mother’s permission).1 In a meta-analysis of 22 trials, (n = 2797) 20 comparing sweeping of membranes with no treatment, three comparing sweeping with prostaglandins and one comparing sweeping with oxytocin, risk of caesarean section was similar between groups. Sweeping of the membranes, performed as a general policy in women at term, was associated with reduced duration of pregnancy and reduced frequency of pregnancy continuing beyond 41 weeks and 42 weeks. It is effective at preventing the need for formal induction in one out of eight women. No evidence of a difference in the risk of maternal or neonatal infection was observed. Discomfort during vaginal examination and other adverse effects (bleeding, irregular contractions) were more frequently reported by women allocated to sweeping. Studies comparing sweeping with prostaglandin administration are of limited sample size and do not provide evidence of benefit. The authors of the meta-analysis concluded that sweeping the membranes is effective in some women at inducing labor, and is generally safe in the absence of other complications, and reduces the need for other forms of induction; however, its rate of effectiveness seems limited.13 Weekly membrane stripping appears to shorten the interval of time to spontaneous labor at term, although improvement in pregnancy outcome has not been demonstrated by large, randomized trials.1 Risks of membrane stripping include premature rupture of membranes, infection, disruptions of occult placenta previa and rupture of vasa previa, though these are rare outcomes of this procedure.

Artificial Rupture of Membranes

Artificial rupture of the membranes (AROM), amniotomy, is performed when the cervix is partially dilated and effaced, and with the fetus in a vertex presentation with the head well applied to the cervix to avoid prolapse of the umbilical cord (or other presenting part). Fetal monitoring accompanies the procedure, as does evaluation of the color of the amniotic fluid to detect for the presence of meconium staining—a possible indication of fetal distress. A Cochrane review identified two trials comprising 50 and 260 women, respectively, that were considered eligible for inclusion in the review of amniotomy alone for labor induction. Conclusions were unable to be drawn on the use of amniotomy alone vs. no intervention, nor amniotomy alone vs. oxytocin alone. When compared with single-dose application of vaginal prostaglandins in women with a favorable cervix in a single center trial, a higher rate of oxytocin augmentation was required in the amniotomy alone group (44% compared with 15%). Combined use of amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin is more effective than amniotomy alone. Limited data suggest that the efficacy of oxytocin plus amniotomy is similar to that of prostaglandins alone.14 Amniotomy is associated with an increase in caesarean section rate. With regard to neonatal outcomes, fewer babies are born with Apgar scores of less than seven, but no statistically or clinically significant differences have been observed in other measures of neonatal morbidity, such as umbilical artery acid-base disturbances and admission to intensive care units.15 Risks of amniotomy include intrauterine infection, umbilical cord prolapse, and disruption of an occult placenta previa or vasa previa with subsequent maternal hemorrhage. Serious complications, however, are rare.12

Prostaglandins

Although the exact mechanisms triggering the onset of labor remain unknown, the production of prostaglandins by the body is implicated in the commencement of cervical ripening and stimulation of uterine contractions. Administration of prostaglandins for labor induction is considered preferable to oxytocin use, as the latter does not lead to cervical ripening but only contractions. The use of prostaglandins for labor stimulation appears to decrease the need for obstetric analgesia, and increases the likelihood of birth without operative delivery within 12 to 24 hours of onset of treatment. These advantages, however, are accompanied by increased risk of uterine hyperstimulation with its increased risk of fetal distress and maternal uterine rupture—a surgical emergency. Prostaglandins used include PGE2 and PGF2α; PGE2 is considered safer and equally effective and therefore is the prostaglandin of choice.12 The optimal route, frequency, and dose of prostaglandins have not been determined. 16 17 18 Dinoprostone, either in the form of Cervidil or Prepidil, both FDA-approved drugs for this purpose, is the agent of choice, and is most commonly administered by direct cervical application via vaginal route, as this has proved to be effective with the fewest side effects. Introduction of IV oxytocin approximately 12 hours after administration of dinoprostone is common practice to facilitate labor onset.

Misoprostol (Cytotec) is a synthetic PGE1 analog available as 100- and 200-µg tablets, which can be broken to provide 25- or 50-µg aliquots and can be administered orally or intravaginally. Misoprostol is approved by the FDA for the prevention and treatment of gastric ulcer disease related to chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use.1 In most countries, it has not been licensed for use in pregnancy; however, off-label use is common because the drug is inexpensive, stable at room temperature (unlike other prostaglandin drugs), and effective in causing cervical ripening and uterine contractions. Misoprostol is highly effective at initiating labor; reduces the need for oxytocin administration, epidurals, and cesarean section; and shortens time to delivery by as much as 8.7 hours.19 The use of misoprostol has been associated with uterine hyperstimulation, tetanic contractions, precipitous labor, and possibly an increased incidence of uterine rupture, which can be fatal for both mother and fetus.19 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes and meconium staining of the amniotic fluid—indicative of fetal distress—are increased with misoprostol use. The optimal dose and timing of misoprostol use remain unknown.

Oral misoprostol appears to be more effective than placebo and is at least as effective as vaginal dinoprostone. However, because of increased risk of uterine hyperstimulation and lack of certainty in dosing, vaginal administration, which is also effective, and associated with a slightly decreased risk of hyperstimulation and other side effects compared with the oral route, is considered preferable.19 If misoprostol is used orally, the dose should not exceed 50 mcg.19 In countries where misoprostol remains unlicensed for the induction of labor, practitioners may prefer to use a licensed product, for example, dinoprostone, for legal reasons.19 Studies to date have not been large enough to determine the actual risk of uterine rupture, which has been anecdotally associated with misoprostol use.20 Misoprostol, however, is contraindicated for women with a history of prior cesarean delivery or other previous major uterine surgery owing to increased risk of uterine rupture. Of particular concern also is the use of misoprostol in the home birth setting, where equipment for adequate measurement of uterine contractions is unavailable, as is rapid access to emergency surgery in the event of fetal distress or uterine rupture.

Mechanical Stimulation Methods

Mechanical methods of labor induction include use of a Foley balloon catheter and hygroscopic dilators. In the former method, a Foley balloon catheter is passed, uninflated, into the undilated cervix and then inflated; it may be used alone or in combination with pharmacologic methods of induction. The combination of balloon catheterization and prostaglandin administration appears to significantly increase the likelihood that a woman will deliver within 24 hours of the procedure; however, the benefit of the two methods combined has not been shown to be more effective than use of oral misoprostol alone. Hygroscopic dilators are inserted into the vaginal canal after application of a topical anesthetic, and gradually swell as they absorb moisture. The swelling, in addition to mechanical effects on the cervix leading to dilatation, may serve to disrupt the chorioamnionic decidual interface, causing lysosomal destruction resulting in prostaglandin release. Laminaria, made from seaweed, is a typical hygroscopic dilator; synthetic agents are also available. Hygroscopic dilators do not appear to be as clinically effective as PGE2 gels and are associated with an increased risk of maternal postpartum infection and neonatal infection.1

MEDICAL APPROACHES TO DYSFUNCTIONAL LABOR

The causes of and medical treatments for dysfunctional labor (dystocia) are extensive. This section provides only a brief overview of the pathophysiology and medical interventions. Labor is considered dysfunctional when any of the stages of labor is protracted with no progress made in cervical dilatation and fetal descent. During the latent phase of labor, it is recommended that women alternate rest or sleep with periods of activity (e.g., walking). Cervical effacement, uterine activity, and fetal status are periodically evaluated. Eight-five percent of women progress to the active phase of labor, 10% cease uterine activity, and approximately 5% require oxytocin induction if it is necessary to expedite labor. If labor dysfunction arises during active phases, the underlying reason for arrest is ideally determined; for example, obstruction resulting from a macrosomic baby or contracted pelvis, or fetal head malposition (e.g., persistent asynclitism). Various methods may be used to facilitate labor, including amniotomy, oxytocin infusion, and epidural or other agents to relax pelvic musculature and allow the mother to rest. The fetus is monitored throughout. If fetal status remains normal and there is minimal risk of cord prolapse, ambulation may be allowed or encouraged. If labor does not progress normally with these, and possibly other interventions, or if fetal status becomes compromised, surgical delivery (cesarean section) ultimately must be performed.

BOTANICAL APPROACHES TO FACILITATING LABOR

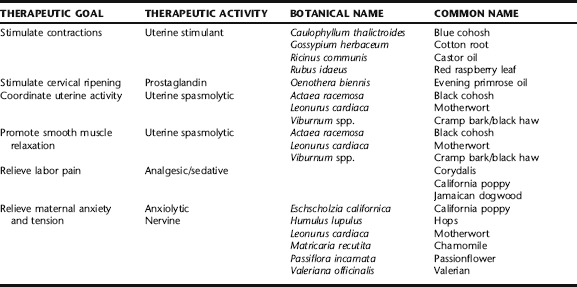

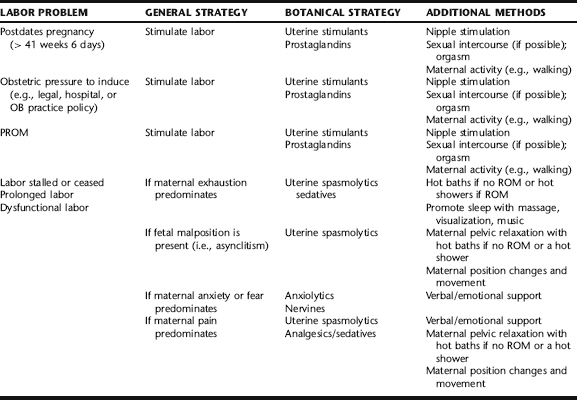

Midwives use a wide variety of approaches to facilitate the onset and progress of labor when these are not occurring spontaneously or when otherwise indicated (Table 16-1). While midwives honor the fact that the timing and pace of labor and birth are highly individual, there are times when legal or medical restrictions require that women birth within certain time parameters, for example, by 41 weeks gestation or within 18 hours of ROM, for women to birth at home in certain states where home birth midwifery is licensed. These constraints require that midwives and their pregnant clients work creatively with a breadth of options in order to expedite labor and birth. Also, birth does not always progress smoothly, obstructed by any number of sometimes benign but nonetheless problematic factors such as malpresentation of the fetal head (persistent asynclitism), maternal fear, anxiety, pain, or pelvic tension. A combination of these factors is very common, as asynclitism can lead to uncoordinated contractions and maternal fatigue, which increase pain, tension, and anxiety—thus creating a vicious cycle that ultimately leads to medical intervention. Often, a combination of agents to alter the maternal response via uterine stimulation or maternal relaxation and noninvasive measures such as nipple stimulation, changes of maternal position, and relaxation techniques can facilitate labor. Rarely is any single technique used in isolation; rather, several techniques are more commonly employed, ideally in an orderly and rhythmic fashion to initiate a healthy, active labor pattern. Botanical choices are selected according to the individual needs and either physiologic or pathophysiologic response to labor, and are used in conjunction with options presented in the section Additional Methods for Facilitating Labor (Table 16-2).

The role of a knowledgeable, supportive care provider, serving as a labor facilitator—a midwife, understanding obstetrician, or doula—cannot be underestimated in its effects on facilitating a healthy labor and birth process. Further, in order to effectively intervene with natural, noninvasive strategies, it is essential that the care provider adequately understand the mechanics, physiology, and psychology of birth. For example, although many think that it is adequate to stimulate contractions in a stalled or dysfunctional labor using uterine stimulants, effective labor required a delicate balance between contraction and relaxation—this yields coordinated uterine contractions, cervical dilatation, and fetal descent. Therefore, it is often more effective to use both uterine stimulant and uterine antispasmodic herbs in combination to achieve an effective labor pattern. Similarly, if a woman is exhausted and contractions are faltering, promoting sleep may actually achieve a better and faster outcome than stimulating contractions. Table 16-2 will help the reader to identify a combination strategy that might be applied to the individual woman. Practitioners must be knowledgeable about when medical intervention becomes required, and of course it is essential that the mother and fetus be adequately and properly monitored during labor, and efforts to stimulate labor. As discussed in the following, blue cohosh, for example, has been associated with rare adverse cardiovascular effects on the fetus, and more commonly with milder side effects as a result of maternal use.

Castor Oil

Castor oil (Fig. 16-1) is a potent cathartic extracted from the castor bean. Use of this herb to stimulate labor appears to date back to ancient Egypt.21 It remains a commonly used folk method to induce labor, and has made its way into obstetric practice, with its use common suggested by midwives. There are scant data evaluating its clinical efficacy. In a clinical trial, a single dose of castor oil was compared with no treatment. There was no evidence of a difference between caesarean section rates, meconium staining of the amniotic fluid, or Apgar score. No data were presented on neonatal or maternal mortality or morbidity. Nausea was a side effect in all women who ingested castor oil.21 Overall, the trial was of poor methodologic quality and no determination can be made regarding efficacy for labor induction.

Blue Cohosh

Caulophyllum thalictroides (blue cohosh) (Fig. 16-2), a native of the eastern and central woodlands of the United States, has been used traditionally and historically as an anticonvulsant, antirheumatic, febrifuge, emetic, sedative, and most notably, a gynecologic aid.22,23 It has been used for labor induction, amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and to induce abortion.22 Blue cohosh was official in the United States Pharmacopoeia from 1882 to 1905 for labor induction, and in the National Formulary from 1916 to 1950.24 It was a major ingredient in the popular Eclectic preparation Mother’s Cordial, which also included Mitchella repens, Rubus idaeus, Actaea racemosa, and Chamaelirium luteum. At least one company (Herbalist and Alchemist, NJ) still makes this preparation; however, the blue cohosh has been removed as an ingredient in the product because of safety concerns. The practice of labor induction with blue cohosh remains a popular choice both among self-prescribers and obstetric professionals in the United States and abroad, with one large survey indicating widespread use among nurse-midwives.25 Blue cohosh is listed in the British Herbal Pharmacopoeia (1983) as a spasmolytic and emmenagogue.26 It may also be used as a uterine and ovarian tonic, and for the treatment of a variety of menstrual complaints, including menorrhagia, amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, and pelvic congestion syndrome.27,28 It is commonly used as a partus preparator to ease parturition, and for labor induction and augmentation.27 It has also been used as an abortifacient.27 Use of blue cohosh during pregnancy is a widespread practice among midwives and pregnant women.25 Maternal ingestion has been associated with a range of fetal and neonatal side effects and adverse outcomes, including fetal tachycardia, increased meconium, profound neonatal congestive heart failure, and perinatal stroke.25, 29 30 31 There is one case report of a neonate born with complications including myocardial infarction and profound congestive heart failure to a mother who ingested blue cohosh as a partus preparator. The newborn remained critically ill for several weeks but eventually recovered. All other causes of myocardial infarction were excluded.30 In another case report, a child was born with severe multiorgan failure associated with the use of a blue and black cohosh combination. The child required significant resuscitation at birth and sustained permanent CNS damage.32 Neither the amount and duration nor preparation used were disclosed. The effects in both cases have been attributed to vasoactive glycosides in the herb. A 21-year-old woman developed symptoms of nicotinic toxicity, including tachycardia, diaphoresis, abdominal pain, vomiting, and muscle weakness and fasciculations after using blue cohosh in an attempt to induce an abortion. These symptoms likely resulted from methylcytosine known present in blue cohosh. The patient’s symptoms resolved over 24 hours and she was discharged.33

Alkaloid and glycoside components in blue cohosh suggest possible mechanisms for these effects, as well as teratogenicity and mutagenicity.33,34 Methylcysteine exhibited teratogenic activity in the rat embryo culture (REC), an in vitro method to detect potential teratogens. Taspine showed high embryotoxicity but no teratogenic activity in the REC.34 Toxic effects of the plant’s constituents include coronary vasoconstriction, tachycardia, hypotension, and respiratory distress.24 However, Low Dog cautions that the quality of the case reports to date and the value of some of the testing methods used to establish toxicity may be questionable. For example, although REC tests have shown teratogenicity and embryotoxicity, “neither the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences nor the Environmental Protection Agency recognizes these tests as an appropriate screen for human reproductive risk.”24 Similarly, it has been speculated that anagyrine, which produces known malformations in ruminant livestock, may do so only after metabolism by microflora in the ruminant gut.24

The Botanical Safety Handbook classifies this herb as 2b, not to be used during pregnancy; however, it states that Caulophyllum may be used as a parturient near term to induce childbirth under the supervision of a qualified practitioner.35 Canadian regulations require that any products containing this herb be labeled as not for use in pregnancy.35 Given the volume of blue cohosh use in the United States alone, and the general paucity of reports of its side effects, as well as a lack of comparison of side effects with conventional medications for labor augmentation (i.e., Pitocin, misoprostol), it remains uncertain how great a risk is posed by the use of blue cohosh, particularly for short-term labor augmentation as opposed to long-term use as a partus preparator. Low Dog states, “The human case reports, flawed as they are, paint a picture that is consistent with the evidence provided by the in vitro and animal studies.”24 The most conservative route is to avoid its use entirely as a partus preparator, and possibly at all during pregnancy, until safety information is established. Midwives and mothers choosing to use blue cohosh to augment labor should observe assiduous fetal heart monitoring during use and should discontinue use promptly if deviations are observed. No discussion on the safety of blue cohosh during lactation is reported in the literature.27 One case report in the literature describes an infant born to a mother who had consumed anagyrine containing goat milk; however, as stated, it is not known whether activation of this compound requires metabolism in the ruminant gut.24 Many direct-entry midwives have discontinued use of the herb because of safety concerns.36

The Use of Herbs as Partus preparators and for Labor Induction

The use of herbs for labor stimulation is popular, both with self-prescription among pregnant women and prescribing by midwives.25, 37 38 39 The pressure to give birth by a certain date in order to avoid artificial induction is the primary incentive behind such use, followed by the desire of pregnant women to avoid protracted pregnancy for personal comfort. In a study by Westfall and Benoit, a panel of 27 women was interviewed in the third trimester of pregnancy, and 23 of the same participants were re-interviewed postpartum (50 interviews total). Many of the women said they favored a natural birth and were opposed to labor induction at the time of the first interview. However, all but one of the ten women who went beyond 40 weeks gestation used self-help measures to stimulate labor. These women did not perceive prolonged pregnancy as a medical problem. Instead, they considered it an inconvenience, a worry to their friends, families, and maternity care providers, and a prolongation of physical discomfort.40

A national survey of 500 members of the American College of Nurse-Midwives and 48 nurse-midwifery programs was conducted by McFarlin et al.25 to determine whether they were formally or informally educating students in the use of herbal preparations for cervical ripening, induction, or augmentation of labor. Ninety surveys were returned from CNMs who used herbal preparations to stimulate labor and 82 were returned from CNMs who did not. Of the CNMs who used herbal preparations to stimulate labor 93% used castor oil, 64% used blue cohosh, 63% used red raspberry leaf, 60% used evening primrose oil, and 45% used black cohosh. The most cited reason for using herbal preparations to stimulate labor was that they are “natural,” whereas the most common reason for not using herbal preparations was the lack of research or experience with the safety of these substances. Although 78% of the CNMs who used herbal preparations to stimulate labor directly prescribed them and 70% indirectly suggested them to clients, only 22% had included them within their written practice protocols. Seventy-five percent of the CNMs who used herbal preparations to stimulate labor used them first or instead of Pitocin. Twenty-one percent reported complications including precipitous labor, tetanic uterine contractions, nausea, and vomiting. CNMs who used herbal preparations to stimulate labor were more likely to deliver at home or in an in-hospital or out-of-hospital birthing center than CNMs who never used herbal preparations to stimulate labor.25

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree